A SPECTRE is haunting Capitol Hill these days. It dogged the Members of the 88th Congress last October when they turned aside from unfinished business to adjourn and make their biennial trek to the hustings. It will confront the 89th Congress when it convenes in January.

The spectre takes the form of a pervasive yet unspoken question: Is there a future for Congress as an institution? Can our national legislature cope with the forces swirling about it - Executive ascendancy, the "technological revolution," and the resulting policy vacuum? Indeed, can it survive its critics, not to mention the ponderous inefficiency of its own machinery?

We have at our backs the manic-depressive cycle of the 88th Congress, whose contrasts are as instructive as they are foreboding. During the spring and summer of 1963 legislative work percolated in committees, and commentators deplored the "torpid spring on Capitol Hill." By the Fourth of July Walter Lippmann, Washington's philosopher-in-residence, was wondering gloomily "what kind of a legislative body is it that will not or cannot legislate?" The situation had changed little by November 22, when the New Frontier- was deprived of its articulate young leader.

Yet by the time the 88th Congress collapsed in fatigue on October 3, 1964, many of its former critics were now speaking of its "distinguished record of achievement." Perhaps President Johnson was' extravagant when he brought out the Marine Band to play a hymn to the 88th Congress (sample line: "Senators and Congressmen of the good old Eighty-eight / are workin' for America, for every town and state"); but there was no denying that the 88th Congress had dealt significantly with such problems as civil rights, tax reduction, nuclear controls, urban transportation, and long-term unemployment.

To many of the critics of Congress, however, the spectacular finish of the 88th Congress was hardly more than a flash in the pan. They contend that the underlying faults of Congress are deeply rooted in the 20th-century policy environment, and will not be cured until Congress itself has changed drastically. The critics' contentions are well worth examining.

Belittling Congress is not a new pastime. A 19th-century British observer, Lord Bryce, observed that "Americans are especially fond of running down their Congressmen." The other branches of our government have nothing quite matching the public image of Senator Snort, the sleazy and loquacious windbag. However alarming the current public outcry against Congress, it is part of the "stuff" of American backfence political discussion.

Yet public criticism of Congress should not be dismissed as frivolous sniping. Since the signing of the Magna Charta, the strong and independent legislature has been among the free man's most cherished possessions. If the current image of Congress is tarnished, then American citizens would do well to give the subject their sober reflection.

What do the critics mean when they charge that Congress is an outmoded institution? More important, what do they expect of a national legislature? There are almost as many criticisms as there are critics, but several recurrent themes can be distinguished.

One motif, particularly evidenced in academic writings, surrounds the criterion of "efficiency." Schooled in the management techniques of large-scale organizations, these observers look with undisguised horror upon the messy inefficiencies of Capitol Hill. There is real question whether bureaucratic tidiness can ever be imprinted on such an overtly political body, but even Congressmen and Senators agree that some tightening of procedures could be effected.

A related criticism is that Congress is slow and unresponsive in dealing with legislation emanating from the Executive Branch. Congressional shilly-shallying with appropriations, for example, often continues beyond the July 1 deadline (the beginning of the federal fiscal year), forcing executive agencies to resort to awkward, make-time procedures until their funds are finally approved. Though these critics usually disclaim ideological favor their comments often belie a preference for Executive policies over Congressional "intervention" and "obstructionism."

A third attack is that Congress is "unrepresentative" of the nation at large. The recent Supreme Court ruling in Wesberry V. Sanders requires that House districts be drawn as equally as possible, but such internal folkways as the seniority system mean that Congressional leadership is drawn disproportionately from such one-party regions as the rural South. These critics usually proceed to the conclusion that Congress is therefore less responsive to the demands of the "urban majority" - often as they are interpreted by the Chief Executive.

A final concern surrounds the question of "Congressional ethics." The fact that Congressmen often wear the dual hats of legislator and lobbyist is especially ironic in light of their zeal in applying rigorous prohibitions of "conflict-of-interest" to executive appointees. Perhaps this issue has been exaggerated beyond its real significance, but it forms a preoccupation for some legislators and a significant portion of the press.

These criticisms of Congress are familiar to most consumers of the news media. Moreover, they are a part of the hoary verities which have for years been dispensed by academics in American government courses. The entire Congressional rogues' gallery - the seniority system, the Rules Committee, inefficient procedures, and so on - add to the general consensus among intellectuals that "something must be done about Congress."

These criticisms are not necessarily wrong or misguided. But they are decidedly deficient in precision or perspective. If we adopt Reform A, how can we be certain it will lead to Desired Result X, rather than Undesired Results Y or Z? And what is more, the reformist argument begs the question of the over-all functions of the national legislature. What is it we want Congress to be? In practical terms, if we enact both Reform A and Reform B, how can we be sure that Results X, Y, and Z will not be at cross-purposes?

Which is to say that reformers often seek divergent goals, sometimes without knowing it. The question of goals - the pattern of results from proposed reforms - is fundamental. Yet the paradox is that reforms typically proceed in a specific, piecemeal fashion.

Proceeding with these assumptions, my colleagues and I decided to undertake an extensive investigation of attitudes toward the over-all place of Congress in the American system, and of views on specific reform proposals. Our first step was to survey a sample of 115 Members of the House of Representatives. The survey instrument was a questionnaire which required from 30 minutes to several hours of each of the Congressmen in our sample. Dartmouth students working in Washington under Public Affairs and Class of 1926 internships were pressed into service for about 40 per cent of the interviews. Like the survey itself, the use of student interviewers was a calculated risk; but we found the students resourceful and effective. Often the Congressmen would talk more freely to a student than to "one of those professors."

Our Congressional survey, begun in July 1963 and completed in the summer of 1964, is the first portion of a comprehensive study of attitudes toward Congress. For example, we are surveying the views of Washington journalists, opinion-leaders in local communities, and the public at large. At each step, our concern will be to illuminate the fundamental question raised by the issue of Congressional reorganization: what is the place of the national legislature in the American political system?

Most of the Congressmen we interviewed evidenced concern over outside criticisms, but many assumed a defensive attitude. Scholars and journalists, they told us, are relatively naive about the day-to-day problems of Capitol Hill life. About 85 per cent of the Members expressed general satisfaction with their own jobs and the performance of the House as a whole. The first-termer typically displayed frustration with the task of learning the ropes on Capitol Hill, but as he moved up the seniority ladder he tended to become more satisfied with the institution. Those in formal leadership positions also tended to be more sanguine about Congress.

This finding recalls Hubert Humphrey's whimsical commentary on the seniority system: "When I first got to the Senate I hated it," he remarked, "but, you know, the longer I stay around the better I like it." This phenomenon has important consequences for the "politics of reform": those who are most able to effect reforms are least disposed to do so.

We were confronted by a striking lack of agreement on criteria or goals for Congressmen. As individuals, they conceive of their jobs in different ways - in part because of their party affiliations, the types of constituencies they represent, and their ideological perspectives.

In analyzing our interviews, we found that individual Members articulated five different roles - to which labels can be attached for clarity. Most common was the "tribune" role - determining, representing, or protecting the interests of the people. Second in frequency was the "ritualist" conception, in which formal aspects of the job - legislation, investigation, or "committee work" - were stressed. The "inventors" were problem-solvers, who viewed their task as formulating specific policies for the general welfare. "Brokers" were those who saw their job as one of balancing geographic and policy interests. The "opportunist" role was the least common, and also the most limited: campaigning and getting reelected.

With these interpretations, it is not surprising that Congressmen also varied in their expectations of the performance of the House as an institution. Our question was: "What role should Congress play in our governmental system?" Many respondents stressed law-making and administrative oversight, though there were conflicting versions of these functions. Other stressed "the power of the purse," representing or communicating with the people, or even specific policy objectives. Still others were more vague, characterizing Congressional functions in terms of "the Constitution" or in some cases failing altogether to conceptualize the role of Congress.

Congressmen were very much at odds with the tendency of many outside observers to judge Congress according to the level of its support for the President's program. Indeed, many Members spoke feelingly of Congress' "surrender" of traditional functions, or of its "rubber-stamping" of Presidential initiatives. This suggests that Congressmen will tend to support reforms that would enlarge their voice in policy formulation and review - a goal not shared by many reformers on the outside.

Are Congressmen, then, likely to be reform-minded? To answer this question, we asked our respondents to react to a list of 32 proposals for change in House organization and procedure. These 32 items were designed to reflect the hundreds of suggestions for change which have been made by political scientists, journalists, and Members themselves.

Institutional reform is clearly not the dominant mood of the House. By combining the responses of all the Members to all of the proposals, we can say that slightly over one-third of the House supports reform as a general proposition; nearly two-thirds oppose it. Those opposing changes, moreover, seem to show more intensity of feeling than those favoring changes.

Not surprisingly, pro-reorganization Members come disproportionately from the ranks of those dissatisfied with their jobs and the House as a whole. Moreover, they tend to feel less effective personally than their colleagues.

Again, seniority and formal leadership position in the House are the most important factors associated with antipathy toward reform. Two groups of Congressmen were found to be particularly friendly to change: first-term "freshmen" and those who had three to five terms (6-10 years) seniority. These two groups apparently feel the limits of existing procedures most acutely: the freshmen "because of the frustrations of learning the ropes, the others because they have been around just long enough to expect more opportunities for leadership than the seniority system affords them.

Formal leadership, of course, is a corollary of seniority in Congress. Non-leaders are about equally split on the issue of reform, but only about one in five formal leaders favors change.

Democrats and Republicans differ little in the level of their support for change. However, Democrats tend to vary more widely in their views, and are over-represented both among those who strongly oppose change and those who strongly advocate it. Opponents and supporters of reform are divided equally in all geographic regions except the South, where only 11 per cent of those interviewed indicated a balance of support for the 32 reorganization items.

What sorts of reforms, then, are Congressmen likely to support? We found that several measures enjoyed a balance of support over opposition - despite divergent views on roles, problems, and outcomes expressed by their proponents. Among these proposals were: increased personal and committee staffing; minority party staffing for committees; reestablishment of the so-called "21-day rule"; publicizing of committee votes; scheduling of more time for committee work at the beginning of annual sessions, and the formal adoption of year-long Congressional sessions with provision for scheduled recesses.

Only four measures, however, were judged by Members to have at least a fifty-fifty chance of adoption by the House in the next decade: broadcasting committee hearings, establishing a committee to study Congressional reorganization, authorizing an administrative assistant for Members, and the holding of year-long Congressional sessions.

Such findings do not augur well for the cause of Congressional reform. But this does not negate the far-reaching developments already being felt by Congress, and by the American governmental system as a whole. The very fact that "Congressional reform" has become an issue is evidence of the developments which produce such changes.

Hopefully, some of the ills will generate self-correcting reactions. The saga of the ugly-duckling 88th Congress is not without its lessons. It cannot be said that Congress reformed itself in the process (though several incremental changes were inaugurated), but the months following President Kennedy's assassination saw a significant body of legislation passed into law. The public outcry against legislative immobilism was at least temporarily muffled. If Congress is a healthy institution, it should respond similarly to future crises of public confidence.

As for the underlying debate over the place of Congress, no one can now say with confidence where it will end. The policy environment of the late 20th century promises continuing strains on our political institutions, with consequent alterations in procedures and substance. As these changes take place, it is hoped that the Dartmouth study will throw light on the nation's reexamination of the role of Congress.

One thing seems clear: a strong and effective national legislature can serve as an energizer, legitimizer, critic, and general gadfly of our political system. As Congress gropes for new procedures and new roles, therefore, all Americans have a stake in its ability to survive.

NOTE: The author would like to thank his co-conspirators in this research, Professors David Kovenock and Michael O'Leary of the Dartmouth Government Department. Our interviewing of Congressmen could hardly have been completed without the willing help of a dozen Dartmouth students, Classes of 1963-66. Especially valuable has been the work of our research assistants, William G. Hamm '64 and James M. Hollabaugh '65. The project has been supported by a grant from the Dartmouth Public Affairs Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureALUMNI COLLEGE 1965

January 1965 -

Feature

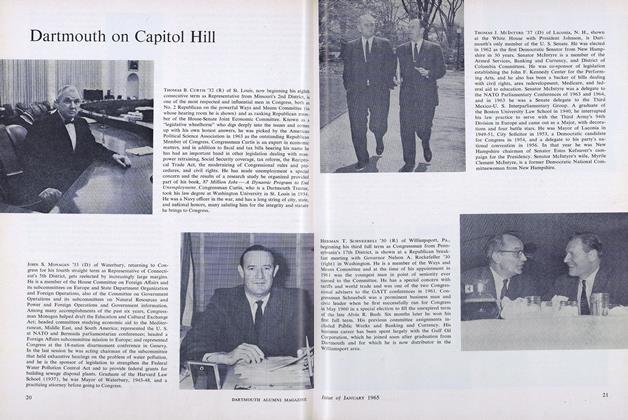

FeatureDartmouth on Capitol Hill

January 1965 -

Article

ArticleA Darwin Letter at Dartmouth

January 1965 By ROBERT M. STECHER '19 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

January 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

January 1965 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, ALBERT W. FREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

January 1965 By ROBERT W. MACMILLEN, DONALD G. RAINIE

ROGER H. DAVIDSON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSocial Responsibility in Painting

November 1959 By CHARLES T. MOREY -

Feature

FeatureUncle Sam and Mother Dartmouth

November 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureArms Control in a Cold War

May 1961 By GENE M. LYONS -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1957 By LLOYD L. WEINREB '57 -

Cover Story

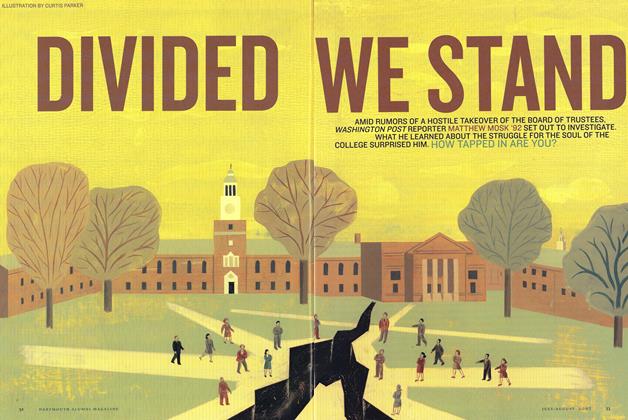

Cover StoryDivided We Stand

July/August 2007 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1958

July 1958 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY