"Take egotism out, and you would castrate the benefactors."- RALPH WALDO EMERSON

INSTRUCTOR IN HISTORY

ESPECIALLY on college and university campuses the civil rights movement has been accorded attention as one of the most important social phenomena of our time. Here at Dartmouth the most recent manifestation of this interest is Professor Bernard Segal's report on the motivation of student freedom workers in the Deep South which appeared in the June issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. I read Segal's findings with interest, especially his conclusion that he was "convinced that it is ridiculous to claim - as one of my colleagues is reported to have done in a recent lecture at the College - that their work is simply a search for identity and recognition." I was not of this mind before reading the article nor am I after, and as the colleague who delivered the lecture in question as part of a course in American social and intellectual history, I feel obligated to issue this rejoinder.

My point was that the freedom worker is as much concerned about satisfying his own personal needs as he is with helping the Negro. Crusades like civil rights, in other words, are undertaken for the crusader as well as against the infidel. In the lecture I endeavored to illustrate this proposition with a brief glance at the history of American reform leading up to the freedom movement.

The history of abolitionism in the 1830's and 1840's, for example, suggests that a fervent belief in the injustice of slavery was not the only factor, and perhaps not the principal one, in bringing men behind the anti-slavery banner. We have learned from the research of several historians that many abolitionists shared backgrounds and characteristics that made them feel uncomfortable and estranged in the burgeoning business civilization of the early 19th century. The typical anti-slavery crusader was a young man who came from an old New England family long accustomed to social dominance. A generation previously these people might have grown up to be landed squires, staunch Federalists, and pillars of their communities. But in Jacksonian America they found themselves overlooked and unwanted. New leaders, the Jacksons and Clays and Crocketts, had passed them by. They were an elite without a following.

In these circumstances the displaced elite leapt at the chance to become abolitionists. Here was a chance to assert their leadership in the kind of moral cause they coveted, and, more broadly, to invest their lives with meaning and importance. One crusader declared: "My life, what has it been? the panting of a soul after eternity - the feeling that there was nothing here to fill the aching void, to provide enjoyment and occupation such as my spirit panted for. ... I seem to be just now awakened ... to a true perception of the end of my being. . . .

Thanks to the A[nti], S[lavery]. cause, it first gave an impetus to my palsied intellect. . . ." Not a single reference to the suffering slave! Instead the statement reveals a mind concerned first and foremost with itself. Helping free the slave was only a means to a very personal end. Abolitionism gave significance to the lives of the abolitionists.

Certainly not all the abolitionists fit the pattern of young men with "panting" souls seeking to overcome alienation, yet the explanation of abolitionism as a means of filling a psychological need gains strength from the coincidence of the movement with a period of rapid and somewhat bewildering change in American life. Why did abolitionism not gather much momentum until the 1830's and 1840's when it recruited an alleged quarter-million Americans? Certainly evidences of the injustice of slavery were present much earlier, and so were the grounds for an ideological or ethical opposition. In 1700 Samuel Sewall wrote The Selling of Joseph, a precursor of Uncle Tom's Cabin, which opposed slavery on grounds of Christian ethics as well as natural rights. In the 18th century the Quakers continued the denunciation, but there was no widespread public response at that time nor at the time of the Declaration of Independence, a document which could well have been construed as opposed to slavery. Not until after 1830 did abolitionism flourish and Harriet Beecher Stowe became the best-selling author of her generation. One reason was that the kinds of people who became abolitionists were previously unconcerned about their status. Only with the beginnings of large-scale industrialization and all it implied did a displaced elite arise and find in abolitionism a way to resist displacement. While an idealistic concern for the Negro in bondage cannot be denied, it had existed over a century without much effect. Consequently, it seems that the crucial factor in precipitating the anti-slavery crusade was the development of men and women who wanted to be abolitionists.

Once the slaves were freed American reform energy concentrated on the rapidly growing cities. In 1889 Jane Addams founded the prototype settlement house in Chicago and two decades later published an account of its work under the title Twenty Years at Hull House. This book revealed a serious concern with bringing light into the dark lives of slum inhabitants, but in a key chapter Miss Addams talked candidly about the importance of Hull House from the viewpoint of the social worker like herself. Declaring that there was a "subjective necessity for social settlements," she pointed out that there were large numbers of young people in her generation who craved a means of expressing their ideals. They wanted to come to grips with the problems of their time, to right wrongs, to make sacrifices, to serve, but there were few outlets for expression of these desires. In fact, Jane Addams admitted that the lives of frustrated friends of humanity "seem to me as pitiful as the other great mass of destitute lives." In this situation the settlement house served a dual function: it gave the social worker a means of satisfying his personal needs at the same time that it ministered to the slum-dweller.

Later in her book Miss Addams made another frank assessment of reformers' motives. Along with humanitarian progress and democratic ideals, she said, must be added "a love of approbation, so vast that it is not content with the treble clapping of delicate hands, but wishes also to hear the brass notes from toughened palms...." Her own life provides a case in point. An ugly, pigeon-toed little girl with a crooked spine, Jane Addams lived in constant fear of becoming an embarrassing failure. For some years she drifted without purpose, thwarted in her desire to serve society. When settlement work became a possibility, she jumped at the opportunity to win approval. This becomes obvious when it is recalled that she liked to be known as "Saint Jane" and took great pride in the fact that one of the Hull House organizations was called the "Jane Club." To be sure, Chicago's poor benefited from Hull House, but its returns to its founder and persons like her were also appreciable.

In recent years the civil rights movement has claimed the attention of American reformers. As in the past, many of its participants fall into a particular social type. On the campus, the largest producer of the freedom movement's personnel, they are of the sneakers-and-beard set - sensitive, thoughtful, and concerned about their identity and the meaning of their lives. In an age of uncertainty these students feel the need of something to affirm. At a time when advanced science and mass society are undermining traditional human values, they want to stand up for the individual with themselves as a case in point. The potential freedom worker is disturbed at his impotence. He craves contact, action, involvement, commitment. Civil rights provides an outlet for these impulses; a way to alleviate internal pressures through attachment to an important cause.

The way these impulses operate to produce enthusiasm for civil rights can be seen on college campuses like Dartmouth's. The student to whom civil rights appeals is, typically, unsatisfied with the undergraduate's tripartite god — sports, sex, and scores on examinations — either because he fails in them or because he succeeds and demands that there be more to life. He may also be impatient with the whole ranch house, country club, station-wagon-with-dalmation-in-the-backseat ethos from which he typically arises. In this situation he looks for something significant and unusual to which to attach himself. Civil rights is made to order. It is currently vital. And it is convenient; he can go south during school vacations or even drop out with a good excuse. Moreover, the freedom movement is newsworthy, and there is always the chance that if he lands in jail, is slugged, or bitten by a police dog, his picture will make the wire services or at least the campus daily! And there is the ultimate prospect of martyrdom. Of course, the student rights worker does not want to die, but it is thrilling to know that others have died in the cause. This knowledge, along with the peril and hardship that Professor Segal discusses, invests his reform activity with excitement and importance. Absorbed into a crusade like civil rights he finds identity and recognition. And so he goes, notebook in hand, on the trail of voter registrations as his predecessors in reform pursued slavery or slum conditions. But at the same time, like them, he is in pursuit of personal satisfaction.

It was with some reluctance, I must confess, that I presented this interpretation to a class in which several of the freedom workers to which I referred sat - Segal's allegedly dedicated idealists. But after the lecture these men came forward to thank me for clarifying thoughts about their own motivation that were in the backs of their minds.

It seems to me that Professor Segal has reported what many freedom workers would like to believe about the source of their motivation, what is on public display. It is time, I believe, for frankness. We should cease regarding those involved in civil rights entirely as saints and consider them more as ordinary people thinking first, as ordinary people do, about themselves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

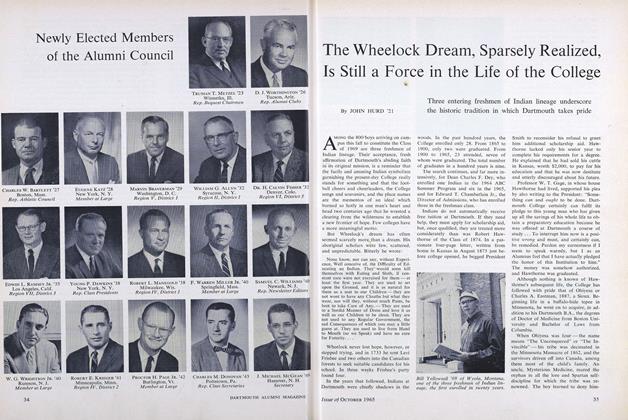

FeatureThe Wheelock Dream, Sparsely Realized, Is Still a Force in the Life of the College

October 1965 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureA Good Summer Press

October 1965 -

Feature

FeatureSUMMER TEMPO IS GO-GO-GO

October 1965 -

Feature

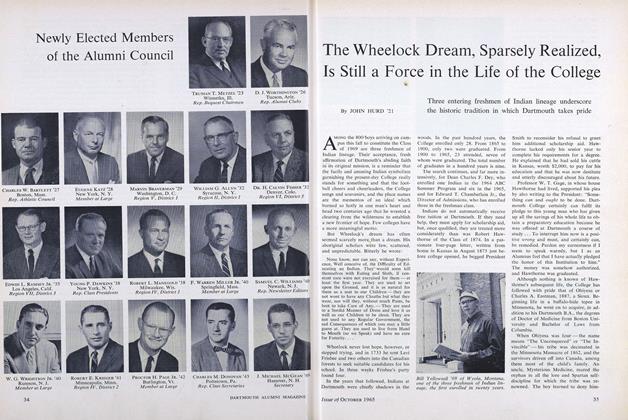

FeatureNewly Elected Members of the Alumni Council

October 1965 -

Article

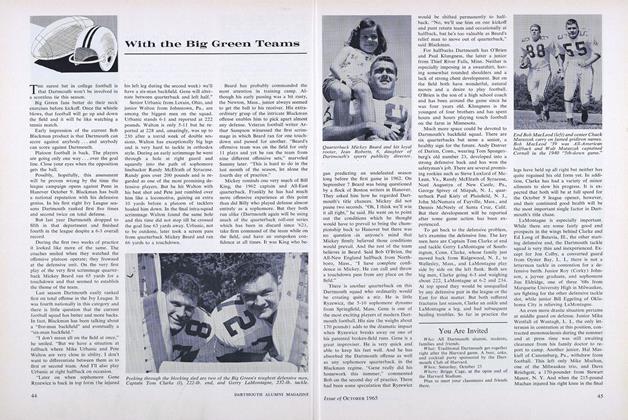

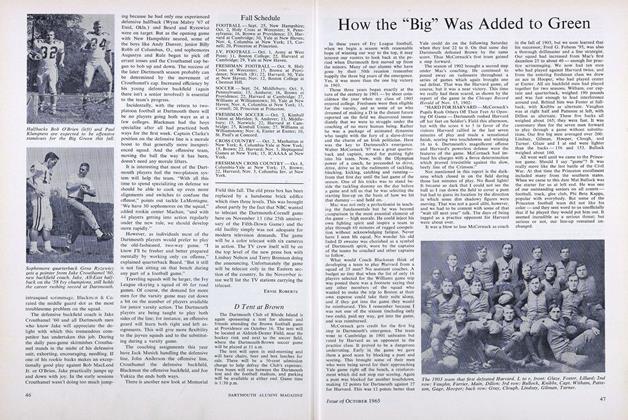

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleHow the "Big" Was Added to Green

October 1965 By W. HUSTON LILLARD '05