In these years of Ivy League football, when we begin a season with reasonable hope of winning our way to the top, it may interest our rooters to look back at the period when Dartmouth first moved up from the minors. Many of our alumni who have gone by their 50th reunion remember happily the three big years of the emergence. Yes, it was more than the one big victory in 1903.

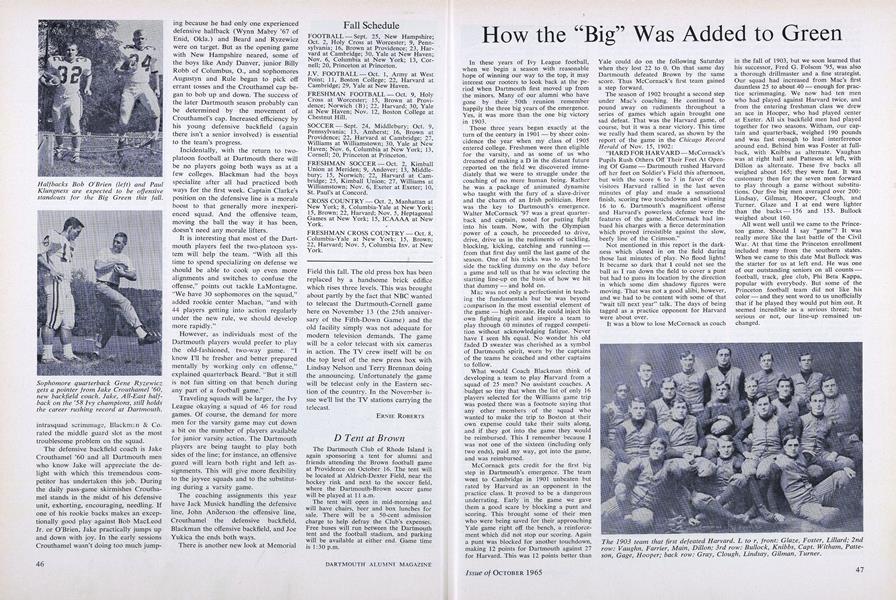

Those three years began exactly at the turn of the century in 1901 - by sheer coincidence the year when my class of 1905 entered college. Freshmen were then eligible for the varsity, and as some of us who dreamed of making a D in the distant future reported on the field we discovered immediately that we were to struggle under the coaching of no mere human being. Rather he was a package of animated dynamite who taught with the fury of a slave-driver and the charm of an Irish politician. Here was the key to Dartmouth's emergence. Walter McCornack '97 was a great quarterback and captain, noted for putting fight into his team. Now, with the Olympian power of a coach, he proceeded to drive, drive, drive us in the rudiments of tackling, blocking, kicking, catching and running - from that first day until the last game of the season. One of his tricks was to stand beside the tackling dummy on the day before a game and tell us that he was selecting the starting line-up on the basis of how we hit that dummy - and hold on.

Mac was not only a perfectionist in teaching the fundamentals but he was beyond comparison in the most essential element of the game - high morale. He could inject his own fighting spirit and inspire a team to play through 60 minutes of rugged competition without acknowledging fatigue. Never have I seen his equal. No wonder his old faded D sweater was cherished as a symbol of Dartmouth spirit, worn by the captains of the teams he coached and other captains to follow.

What would Coach Blackman think of developing a team to play Harvard from a squad of 25 men? No assistant coaches. A budget so tiny that when the list of only 16 players selected for the Williams game trip was posted there was a footnote saying that any other members of the squad who wanted to make the trip to Boston at their own expense could take their suits along, and if they got into the game they would be reimbursed. This I remember because I was not one of the sixteen (including only two ends), paid my way, got into the game, and was reimbursed.

McCornack gets credit for the first big step in Dartmouth's emergence. The team went to Cambridge in 1901 unbeaten but rated by Harvard as an opponent in the practice class. It proved to be a dangerous underrating. Early in the game we gave them a good scare by blocking a punt and scoring. This brought some of their men who were being saved for their approaching Yale game right off the bench, a reinforcement which did not stop our scoring. Again a punt was blocked for another touchdown, making 12 points for Dartmouth against 27 for Harvard. This was 12 points better than Yale could do on the following Saturday when they lost 22 to 0. On that same day Dartmouth defeated Brown by the same score. Thus McCornack's first team gained a step forward.

The season of 1902 brought a second step under Mac's coaching. He continued to pound away on rudiments throughout a series of games which again brought one sad defeat. That was the Harvard game, of course, but it was a near victory. This time we really had them scared, as shown by the report of the game in the Chicago RecordHerald of Nov. 15, 1902:

"HARD FOR HARVARD — McCornack's Pupils Rush Others Off Their Feet At Opening Of Game - Dartmouth rushed Harvard off her feet on Soldier's Field this afternoon, but with the score 6 to 5 in favor of the visitors Harvard rallied in the last seven minutes of play and made a sensational finish, scoring two touchdowns and winning 16 to 6. Dartmouth's magnificent offense and Harvard's powerless defense were the features of the game. McCornack had imbued his charges with a fierce determination which proved irresistible against the slow, beefy line of the Crimson."

Not mentioned in this report is the darkness which closed in on the field during those last minutes of play. No flood lights! It became so dark that I could not see the ball as I ran down the field to cover a punt but had to guess its location by the direction in which some dim shadowy figures were moving. That was not a good alibi, however, and we had to be content with some of that "wait till next year" talk. The days of being tagged as a practice opponent for Harvard were about over.

It was a blow to lose McCornack as coach in the fall of 1903, but we soon learned that his successor, Fred G. Folsom '95, was also a thorough drillmaster and a fine strategist. Our squad had increased from Mac's first dauntless 25 to about 40 - enough for practice scrimmaging. We now had ten men who had played against Harvard twice, and from the entering freshman class we drew an ace in Hooper, who had played center at Exeter. All six backfield men had played together for two seasons. Witham, our captain and quarterback, weighed 190 pounds and was fast enough to lead interference around end. Behind him was Foster at fullback, with Knibbs as alternate. Vaughan was at right half and Patteson at left, with Dillon as alternate. These five backs all weighed about 165; they were fast. It was customary then for the seven men forward to play through a game without substitutions. Our five big men averaged over 200: Lindsay, Gilman, Hooper, Clough, and Turner. Glaze and I at end were lighter than the backs — 156 and 153. Bullock weighed about 160.

All went well until we came to the Princeton game. Should I say "game"? It was really more like the last battle of the Civil War. At that time the Princeton enrollment included many from the southern states. When we came to this date Mat Bullock was the starter for us at left end. He was one of our outstanding seniors on all counts - football, track, glee club, Phi Beta Kappa, popular with everybody. But some of the Princeton football team did not like his color - and they sent word to us unofficially that if he played they would put him out. It seemed incredible as a serious threat; but serious or not, our line-up remained unchanged.

Only a few minutes after the game started Mat ran down the field to cover a punt, made his tackle, and was piled on viciously. The result was a broken collar bone, which kept him out of play for the rest of the season. It was a case of deliberate mayhem. There was no penalty imposed on the offending players. The game degenerated into a real Donnybrook battle in which all of us fought without any restraint from the blind officials. I can say this with reason, for after I shared in an open exchange the alleged umpire told me to leave the field. Whereupon I ran to the sidelines, and told our coach that I was going right back. He nodded approval, I ran happily back, and fought the rest of the battle with no objection by the officials - an all-time record of total official blindness!

Then came the big test against Harvard on November 14 in their new stadium, the first one built in our country. As we read about the opposing line-up in the morning papers we were surprised to find two names that would not be eligible under present regulations. Their fullback, Schoellkopt, had been captain and fullback at Cornell the previous year; and there was Andrew Marshall '01 at right guard who had played guard for Dartmouth. Both were then in the law school at Harvard.

As we waited for the whistle to blow for the first kickoff the men in green jerseys were nervous, as usual, but not worried. We confronted the crimson jerseys with no inferiority complex. Rather we were almost handicapped by overconfidence. Our defense looked secure. We were confident we could stop their line-bucks, cross-tackle plays, end sweeps, and trick delays.

Offense was a different story from the present. We had three downs in which to gain five yards. No forward passing. Averaging 2½ yards meant success. If we made only 4 yards in two downs we had to punt. No huddles between plays were allowed, which meant that all signaling was by numbers from the quarterback. He chose the plays instead of waiting for a string of messenger boys sent in by the coach as at present. Goals after touchdowns were more difficult. The ball was brought into the field straight from the spot of the touchdown as far as desired by the kicker for a favorable angle. This sometimes meant a long and difficult kick.

For an objective story of the game that followed I may refer to the Boston Herald of November 15, 1903:

TOUGH DEFEAT IN THE NEW STADIUM CRIMSON ELEVEN COMPLETELY OUTPLAYED

"Dartmouth defeated Harvard yesterday in the initial game in the new Stadium by the score of 11 to 0. It was a clean game of straight football won by the better team. Harvard was fairly outclassed in every part of the game and at every place on the team, and after the game the wonder was that Dartmouth did not win by a larger score.

. . . If Harvard had the offensive strength which seemed to show in the Pennsylvania game, it proved powerless against the Dartmouth linemen, who towered above their crimson rivals and who showed speed and aggressiveness not expected from men of their size and weight. On the defensive Harvard was just as weak as she has shown herself throughout the whole season and Dartmouth had an offense which would do credit to any team in the country. Her backs were fast, her linemen lifted with the snap of the ball, and the whole team got into every play in splendid style. In fact there could be no apologies or excuses from the Harvard team, as they were up against a heavier, faster and more skillful team, and they were played to a standstill.

"Dartmouth kicked off, and Hurley ran in to the 32-yard line, and after Harvard failed to gain on two tries Hurley fumbled. From there it was easy going for Dartmouth, and she scored in thirteen plays. Dartmouth kept the ball for the greater part of the first half, but although she got to Harvard's 38-yard line she was unable to score. Harvard took the ball twice on downs but was unable to make any progress and never had possession of the leather within 60 yards of the Dartmouth goal during the first half.

"In the second half Harvard seemed to have the better of it for a moment but after getting the ball on Dartmouth's 42-yard line and advancing 15 yards, lost it on downs at the 27-yard line, which was the nearest she came to scoring during the whole game.

"After Dartmouth secured the ball on this play she showed her greatest strength, and by steady rushing, with gains of two or three yards, she carried the ball down the field for a touchdown. Dartmouth's attack consisted chiefly of a regular back formation, and although Vaughan, Patteson, Foster, Dillon and Knibbs played hard, fast football it was the men in the line who made the gains possible. Hooper at center was masterful, and on every play he went through the Harvard line pushing everything before him. Vaughan played a brilliant game and made the only two gains of the afternoon which covered more than one chalk mark. In the first half he got free around right end and ran 40 yards before he was brought down by C. Marshall. In the second half he got started around right end once more but was brought down after he had covered 10 yards on a beautiful tackle by Hurley. With these two exceptions the game was simply a question of hammer and tongs with Dartmouth playing winning football from start to finish.

"When Harvard had the ball it was between the 25-yard lines so that she could not use her tackle back play as did Dartmouth when Turner was used to score both touchdowns; they lost more on the ends than they gained. Schoellkopt played fierce football but unaided could make no impression on the Dartmouth line. Carl Marshall tried to get around Dartmouth's left end on a direct pass, but the whole side of Dartmouth's line was through on him and he was brought down for a loss."

Dartmouth held the ball for 88 plays and gained a total of 236 yards.

Harvard had 29 plays and gained 48 yards.

That was it. Dartmouth had emerged! And we celebrated by defeating Brown on the next Saturday by 62 to 0.

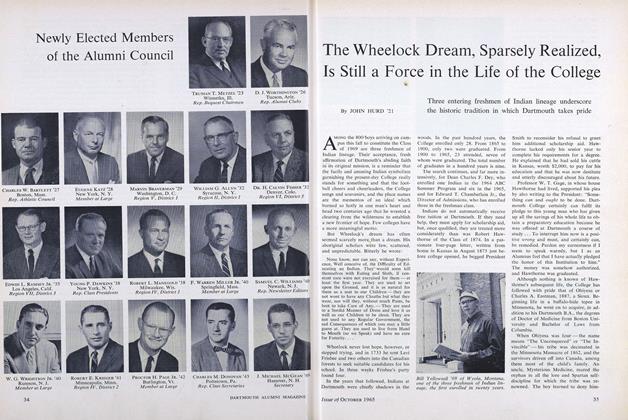

Left End

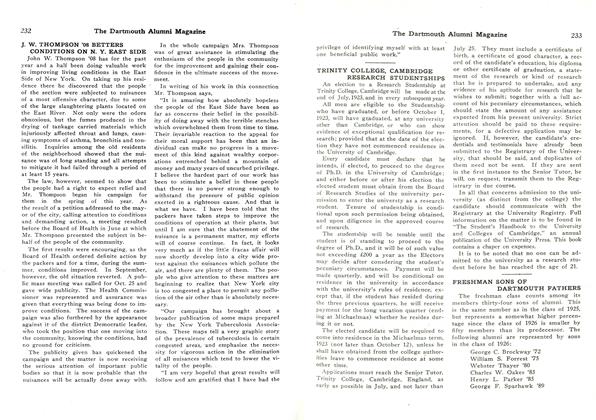

The 1903 team that first defeated Harvard. L to r, front: Glaze, Foster, Lillard; 2ndrow: Vaughn, Farrier, Main, Dillon; 3rd row: Bullock, Knibbs, Capt. Witham, Patteson, Gage, Hooper; back row: Gray, Clough, Lindsay, Gilman, Turner.

Mr. Lillard, who resides in Cohasset,Mass., was Headmaster of Tabor Academyfrom 1916 to 1942. Before that he taughtEnglish, coached football, and was assistantto the headmaster at Phillips Academy,Andover.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

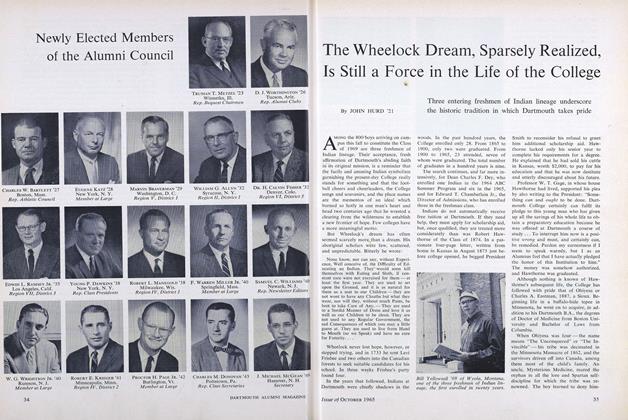

FeatureThe Wheelock Dream, Sparsely Realized, Is Still a Force in the Life of the College

October 1965 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureA Good Summer Press

October 1965 -

Feature

FeatureSUMMER TEMPO IS GO-GO-GO

October 1965 -

Feature

FeatureNewly Elected Members of the Alumni Council

October 1965 -

Article

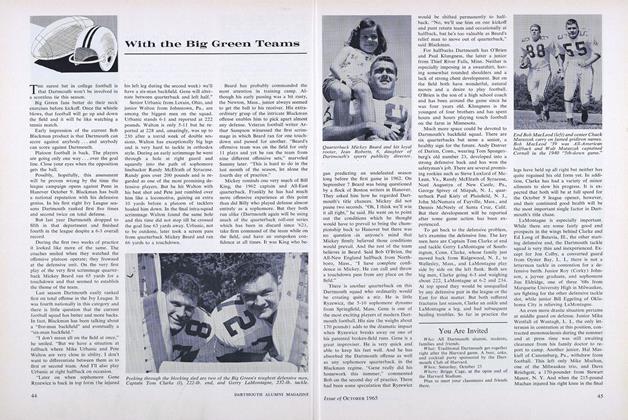

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleA Rejoinder to Professor Segal's Article

October 1965 By RODERICK NASH

W. HUSTON LILLARD '05

Article

-

Article

ArticleBOOK OF THE INAUGURATION OF PRESIDENT NICHOLS

-

Article

ArticleNEWTON ALUMNI DEBATE

-

Article

ArticleTRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE RESEARCH STUDENTSHIPS

January, 1923 -

Article

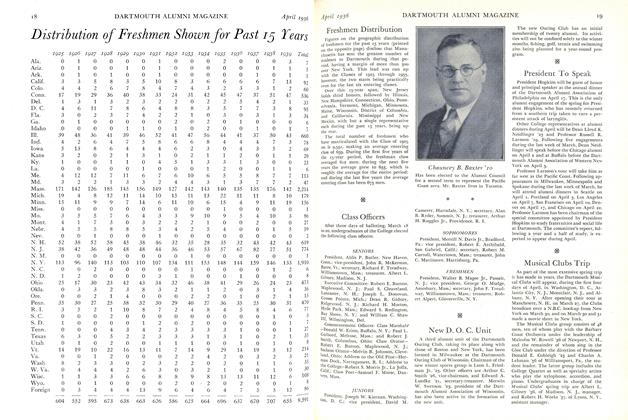

ArticleDistribution of Freshmen Shown for past 15 Years

April 1936 -

Article

ArticleSquash

March 1954 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

Article"NEW SPIRIT"

March 1934 By S.H. Silverman '34