Dean Unsworth Defended

TO THE EDITOR:

The February issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE published four letters commenting on Dean Unsworth's speech, "Vanishing Absolutes." The comments ranged from neutral to highly critical. In large part they dealt with Dean Unsworth's examples rather than his message.

His message was addressed to college freshmen. It is well known that many men of that age are in a rejecting and questioning period of life. There is plenty of evidence that many such men no longer accept the old absolutes on faith, and that they do not follow that which they do not accept. There is a consequent tendency to leave a vacuum or to create nihilism in the area of personal ethics.

Dean Unsworth's speech would presumably not influence the men who hold to the absolutes. It does offer a meaningful alternative to those who reject or question the absolutes or simply fail to understand them enough to apply them in everyday life.

The absolutes are in many ways mere details of two broader rules, "love thy neighbor as thyself" and "do unto others as you would have them do unto you." The "ethic of service" concept is consistent with those two rules. At the same time it may be easier to understand and practice for those who cannot accept absolutes on faith and will not follow ethical rules whose source and significance escapes them.

Moreover, the "ethic of service" can be a transitory stage which will allow men to return to older forms of absolutes when their own maturity and experience enables them to accept those absolutes as fundamental rules, which as all other rules, may have exceptions or subtleties of application.

How many of the "vanishing absolutes" are likely to be violated by a man who is guided by "an ethic of service which stresses sensitivity, responsibility and usefulness" (as the Dean defined those terms)?

The issue is not whether Dean Unsworth has offered a "perfect solution." It is whether he has made a constructive proposal. To the extent that his "ethic of service" will fill a void, which is bad either as a continuing void or as a fertile spot for the growth of undisciplined selfishness - to that extent at the least - Dean Unsworth has indeed performed a constructive service.

Rye, N. Y.

Praise for a Colleague

TO THE EDITOR:

I should like to register a protest at the abusive personal attack on Dean Unsworth (in the February issue) by Gilbert L. Wolfe '31. As the preceding letters, from Donald J. Tobin and Tom Marx, indicated so neatly, one may differ with a man's opinions without thereby indulging in nasty comments about the man himself.

May a colleague of Dean Unsworth, who works with, and learns from him day by day, assure Mr. Wolfe that the Dean of the Tucker Foundation is not "removed from the reality of the daily life," and does not represent the "decline of Dartmouth 'guts'," but on the contrary, has brought a rigorous and humane intellect and a keen, penetrating commitment on fundamental issues to our midst. He also happens to be a fine gentleman.

Assistant Professor of Religion

Hanover, N. H.

Winship Article Rebutted

TO THE EDITOR!

In your February edition, Addison L. Winship takes issue with my Wall Street Journal article showing that college students are increasingly turning away from business careers. He charges that reports of this trend are "based in good part upon half-truths and in total they represent a distortion of the facts." In this connection, I would like to make a few points:

Mr. Winship reports that 31% of the 640 men who graduated in 1963 said they planned business careers. No figures on previous Dartmouth graduates are given for comparison. But a check with your alumni records office shows that more than 54% of Dartmouth graduates in general are businessmen. (Categories counted as "business" conform to those used by Mr. Winship.)

Your article is undoubtedly right when it says that a number of students will later switch to business careers. But in order for the 1963 graduates to match their predecessors' 54% record, 145 or 33% of the 440 men who didn't plan careers in business would have to switch to this field. And the 145 figure is a minimum valid only if notone single man choosing business at graduation switches to another career later. In any event, to reach the 54% level, the percentage of the non-business group switching would have to exceed the percentage of the whole class that chose business in the first place.

Dartmouth unfortunately didn't have available figures on the percentage of alumni actually changing to business after they leave the college. But five years after graduation (by which time most career decisions should be fairly firm), only a net of 4% of another private Eastern college's class of 1959 had switched to this field. This is a far cry from the 23% that Dartmouth's class of 1963 would need to reach the 54% figure. Based on these figures, it seems fairly evident that the percentage of Dartmouth men entering business is, in fact, declining.

Furthermore, Mr. Winship says: "To the charge that the faculty brings anti-business persuasion to bear on students, the Dartmouth study suggests this simply is not so." Conversations with five of your recent graduates inform me that professors do express a good deal of anti-business sentiment in class and out, which of course is their privilege.

But even if the trend I discussed were completely absent at Dartmouth, it wouldn't in the least destroy the validity of my story. As I explained very early in my article, the move away from business isn't found at some colleges at all.

This brings me to my strongest objection to your article, namely that its accusations go far beyond the area for which it offers evidence. Conceding that he can "speak only from the evidence found on this campus," and offering no substantiation whatsoever, Mr. Winship says he believes reports of the trends I discuss "are an exaggeration of the situation on other campuses as well."

I anticipated that some college officials would try to prove that my story doesn't apply to their particular institution (and in some cases they would be right). An article such as mine certainly doesn't help a college's relations with business and with alumni in business. But particularly when I said that the trend reported varied from place to place, I am surprised that a writer would attack a story on colleges generally by citing evidence at only one.

New York, N. Y.

Doc Griggs

TO THE EDITOR:

I am distressed that in the memorial comments on the passing of my great friend Doc Griggs, in your October and November issues, there is nothing to indicate the depth of his thinking, to say nothing of the concordance of his views with those expressed in the splendid address by David Weber.

Doc Griggs was far more than a folk character. For my money, he was the wisest and most brilliant member of the Dartmouth faculty during his epoch. On many a crisp morning I sought him to learn his reactions to a new critique of Sir James Jeans, or a new cosmology, or a revolutionary ecological concept. He, himself, admired most such stimulating professors as Herb West, Wing-tsit Chan, and Jerry Lathrop. In short, Leland Griggs was a Philosopher, in the finest, broadest sense of the word. Natural History (now called Ecology) was only the vehicle by which he strove, successfully, to reconcile the diverse and conflicting currents of life - from Psi U to DOC to DCU - and far beyond. Truly, he was a "whole man," and he deeply detested the shallow and the fraudulent types who are always with us. It is to his great credit as a human being that he welcomed them to strawberry shortcake feeds, in the hope that they might be partially saved. But he would writhe to think that he was remembered only for such frolics.

Doc loved to laugh, but he was a mighty realist and a mighty mystic as well. Let's hoist a Gibson to the hope that Dartmouth will produce many more like him!

Recife, Brazil

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

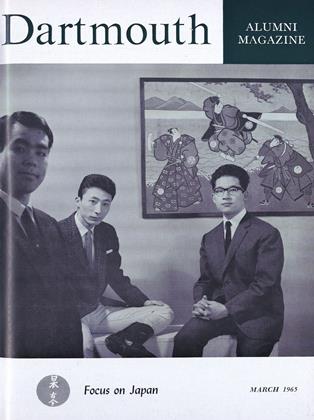

FeatureTHE EDUCATION LADDER

March 1965 By PROF. BURTON E. MARTIN '33 -

Feature

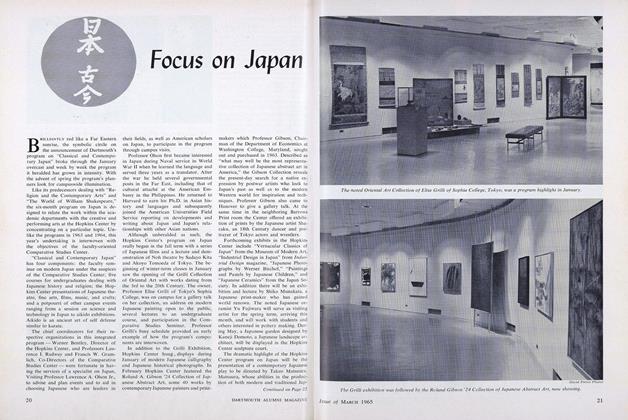

FeatureFocus on

March 1965 -

Feature

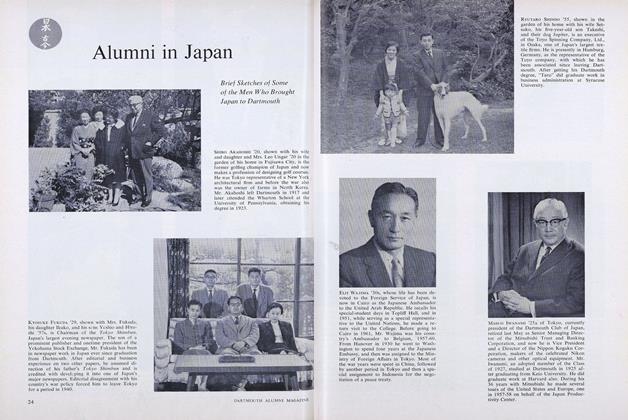

FeatureAlumni in Japan

March 1965 -

Feature

FeatureHonorable President in Japan

March 1965 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

March 1965 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HARRISON F. CONDON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1965 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, ALBERT W. FREY

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA SUCCESSFUL DARTMOUTH COACH

December 1916 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

January 1924 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

November 1939 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

June 1953 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

OCTOBER 1970 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorDiana's Story

MARCH 1999