Climbing it can be a traumatic experience for Japanese boysand girls and a lifelong tragedy for a great many who fail

WASEDA UNIVERSITY, TOKYO

A RE any people in the world more clamorous for higher education than the Japanese people? I know of none.

In the capital city of Japan there are fourteen universities which are state supported, and 75 private ones - 89 universities in one city! Outside of Tokyo, in the provinces of the land, there are 202 more. Nor is that all; in addition to these which are four-year institutions, there are the two-year ones, like technical schools and junior colleges, of which there are 339. The grand total, according to the Japanese Ministry of Education, is 630 institutions of higher education.

It is not quite so easy to obtain the numbers of students enrolled, since some schools have their own reasons (taxes, for example) for not wanting the exact numbers to be published. However, if the largest universities in Tokyo were to pool their student populations, the number would be approximately 170,000 (roughly: 33,000 plus 41,000 plus 96,000). I have been warned that this is a conservative estimate, and there is the the colossal rumor that the largest university of the lot has passed the 100,000 mark.

Are 630 institutions of higher education sufficient for the needs of Japan? Some say flatly, "No." Others tell me that there are enough mediocre institutions, not enough best ones, and that one of the main troubles is that everybody is trying to enter the best universities. The struggle to enter the best is clamorous. At this university, one enters out of every eight who try; at that university, it is one out of every , fourteen. Symbolically, then, at this university 200 pass, 1,600 fail; at that university, 500 pass and 7,000 fail. Every year.

Higher education is one of Japan's thriving industries, more thriving than wealthy, but so thriving and so industrious that its influences, almost inestimably great, are at once vital and also vicious. The whole Japanese educational ladder, from kindergarten bottom to university top, is a vital and vicious ladder affecting those who climb and succeed as well as those who fail and fall ... as we shall see.

FIRST, however, let me introduce to you a Japanese university. I have chosen the University of Waseda because I admire it and because I know it best. During my years of association with this fine, large, thriving and industrious institution I have found something which resembles the Dartmouth spirit. I cannot say that Waseda is the Dartmouth of Japan ... I rather doubt if Japan has a Dartmouth . . . yet I do see, along with many differences, some similarities.

Dartmouth and Waseda are private schools.

Dartmouth was named after Lord Dartmouth; Lord Okuma, a noble and benevolent Japanese statesman, was the founder of Waseda.

Both Dartmouth and Waseda are old in relation to their country's history of higher education; Dartmouth is the older in years, Waseda is not yet a hundred; when the one was born in America and the other was born in Japan there were very few other institutions of the kind in either nation; therefore each was a pioneer in its country's cultivated growth; each continues to be, and ever increasingly, so.

Alumni loyalty! In the fervor of this loyalty I can find no difference between men of Waseda and men of Dartmouth. Here, and in sportsmanship, I find the Waseda spirit coming closest to the Dartmouth spirit. Both are schools where sports stand high (this is not true of all Japanese universities), where sportsmanship is a living fibre in the school spirit. A Waseda-Keio baseball game resembles a Dartmouth-Harvard football game, if only in excitement. During the 1964 Tokyo Olympics the Waseda gymnasium was chosen for the fencing events and Waseda likes to think that its spirit has something of the Olympics in it.

Waseda has no entrance gate and Dartmouth has no entrance gate. Dartmouth men do not make much, if anything, of this fact, but Waseda men do. They say it is one symbol of the university's relations with society. True, Waseda has its back and side gates which at times are shut, but the front is gateless and open to the world.

Then there are the differences. Dartmouth is in a small town whereas Waseda is in a giant metropolis. Dartmouth can still reach out and with its fingertips touch fields and hills. Waseda cannot; it is huddled in, like an academic Vatican City, on a single campus not so far from the center of Tokyo.

Dartmouth has no smog; Waseda rarely has snow and can never keep it. Waseda is one of the largest universities in Japan, not the largest by any means, with more teachers on its staff than Dartmouth has students.

Men of Waseda will have to tell you, possibly not without concern, that their university is co-educational and the women are increasing overwhelmingly. For every girl who enters, a boy cannot. "For them it is a luxury, for us a necessity." Prosperity is one reason for this great new influx, another is that it. has become more fashionable for girls to go to universities, and . . . the average intelligent Japanese girl studies more persistently than the average intelligent Japanese boy. "Boys beware!" the boys keep bewaring each other. One told me, mournfully, "Girls have a talent for passing entrance examinations."

(There is one Waseda tradition which I should like to mention. Slightly over a generation ago the noted and unique Japanese scholar, Tsubouchi Shoyo, was translating Shakespeare and lecturing on his dramas at Waseda. He was the man who translated all of Shakespeare, from A to Z, into Japanese. His lectures, unfortunately before, my time, are said to have been not only sincere and scholarly but vivid and dramatic. He could reduce his student audiences to laughter or to tears and make Shakespeare a living part of their lives. The Shoyo Tradition is still alive and I, who teach Shakespeare as well as Frost, like to think that I too am part of that tradition.)

Waseda graduates take active parts in the life of the Japanese nation; they are particularly active in politics, and some are statesmen in the footsteps of the school's founder, Lord Okuma; others are important in the Japanese theater, in literature too and in architecture; many, a great many indeed, are influential in the mass-media worlds of newspaper, radio, and television; others are distinguished lawyers, bankers, and big men of big business. There are also the men and women of more modest achievement, naturally, and a few who have not done very well at all. However, the Waseda University alumni group as a whole can be called an impressive, formidable, creative and leading force in the life of the nation. "If Waseda did not exist, Japan today would not be the same!" These are sterling words of staunch loyalty, not without bias . . . and not without truth.

Other universities in Japan can claim the same truth. They should. Waseda, like its great, good, deadly rival, Keio University, like Tokyo University, Hitotsubashi, Gakushuin, Kyoto, Osaka, Tohoku, and a few others, may be among the best in the top 2% of Japan's universities, but there are 600 others. The total impact upon the nation is mountainous; tear them down and take them away and the islands of Japan are stripped of their mountains. Yet, if the universities are going to claim glory and take credit for the good in today's Japan, must they not also take some blame with much responsibility for the ills?

As the entire subject is too vast for an L article of this size, I shall limit myself to the set of good-and-ills revolving around the entrance examinations. Those two prosaic words cannot convey the drama they create in the life of the Japanese nation.

The universities may be vital to the lives of those who can enter them, disastrous to the lives of those who cannot. The positive thinking of the Japanese people is that a boy's future is made or ruined when he succeeds or fails to enter a university. Facts do result from suchrooted attitudes. Important as the universities themselves are, adulation lends them an added importance.

It is not so essential for a Japanese girl, not nearly; the stress of urgency is not there; pride and glory, yes, but not live or die. For most girls a university education is a very nice thing to have; very few Japanese young women hold a job longer than those brief years between the diploma and the wedding wines.

For a boy it is essential; at least everybody tells him so, sincerely, insistently, urgently, his father and mother, his grandfather and grandmother, his uncles and aunts, his teachers, his friends, everybody. Before adolescence is spent he has heard that the gods in heaven want only university boys, heaven being the world of jobs and the gods being the men who can bestow them. The long educational ladder up from kindergarten through elementary secondary schools, up through the university at the top, stops there for most, but it continues to point on up into the heavenly clouds of blessed security. There the gods sit behind great desks dispensing security to boys with diplomas, particularly to boys with diplomas from the best universities. Those are the gods revered by a multitude of parents because they have in their hands a boy's salvation, his whole future life on this earth.

The necessary gate to this salvation is the one near the top of the educational ladder on the threshold of the university, and it is guarded by that devil Monster named Entrance Examinations. No one likes him, his unpopularity is complete, but his power is absolute, he casts a devouring shadow darkly down the educational ladder, and he is accepted as a melancholic, indispensable evil. The gate he guards is blessed.

Failure remains outside the gate; success resides within. That is Japan, and so is the following: Japanese institutions areloyal to those who are allowed to enter. Once a student is in a university, he has every chance of being graduated; once graduated, he has a very good chance of getting a job; once in the job, the chances are he will be kept on it until his age of retirement. Chance, in all three of these opportunities, depends upon good behavior and a modest willingness to work. The master key that can open all gates into the future is in the university entrance examinations, and once they are passed that key is in the boy's hand.

Waseda has no entrance gate that one can see but it has the invisible gate of entrance examinations, over which ABANDON FAILURE ALL YE WHOENTER HERE is written, invisibly.

PARENTS stand beside the educational ladder and watch their child climb or fall. They may help him to climb, many enlightened parents do, but the one thing they are most certain of doing is to push. They push, encourage, threaten, and push again; they push some children beyond their native abilities, they push most children beyond good health; for every youngster it is a painful, exhausting, and unhealthful climb. Also, ambitious teachers are pushers. They join in what solemnly may be called the PT Pushing Association of Japan.

High Schools compete with each other, taking great pride in the number of their students who enter the best universities; Middle Schools compete with each other, taking great pride in the number of their students who enter the best upper schools. The Monster's shadow shuttles down the ladder. University entrance examinations —> High School entrance examinations —> Middle School —> Kindergarten; even kindergartens are becoming more difficult to enter. The Monster's shadow hits the ground at the bottom of the ladder.

School teachers and school principals are the human embodiments of these competitive school prides. They coax, cajole, exhort, push, and punish the students, they drive them to do their best, to do better than their best, demanding sometimes the impossible. Too often (but not always) such teachers teach with one eye directed up the ladder to the entrance examination on the next rung, and this may color or even determine what and how they teach. This does happen. They cram the student heads with examination fodder; rote memory is encouraged, not creative thinking.

Japanese children, who by their very nature take all this with fatal seriousness, push themselves harder and harder as the goal of an examination is approached. This fatal seriousness of theirs may be the simple root of the entire system: where there is a will there is an endurance. And once again we should mention the parents; they abet the teachers, even pushing them to push, while the parents themselves are being pushed by their parents. Parents are the most involved and invested part of the PT Pushing Association.

The children who do not plan to take an entrance examination, and those who are not likely to pass, may be neglected. (I must state strongly that this is not always the case. There are teachers who love children and education for their own sakes!) Yet this is one danger in the system. Students who are thus neglected, or who feel so even if they are not, are highly potential juvenile delinquents. In a country like Japan which has a major delinquency problem, this is a tragic danger. The Monster near the top of the ladder is partly, indirectly, and insouciantly to blame.

Students who try and fail an entrance examination, especially the university one, are abysmally disappointed. Failure is not pampered in Japan; more often it is punished. It is punished infrequently these days by the rod or a slap across the face, more frequently and most painfully by frozen words and frozen attitudes from frozen PT hearts. The students feel ashamed, discouraged, disconsolate, insecure, and afraid. Kept outside the limbo of heaven, they enter the limbo of hell . . . "We have no reason to live." The bravest of these plod pluckily back to the farm or go to work in father's fish shop or join groups of day laborers; some enter those schools which exist to cram youths for another try at some university examination; many run away from home to the temptations and perils of cities already overpopulated with such failures; some drift into gangs of hoodlums, the violently maladjusted; and some jump off a cliff or into the path of a train.

Two hundred passed, but 1,600 failed at that university; at this, 500 passed, 7,000 failed.

Those who succeed are very happy indeed, the lucky blessed ones who having struggled with the Monster, and won, can pass straight through the gate, visible or invisible, into the limbo of heaven. They rejoice, their teachers rejoice with them, and their parents rejoice most of all. It was worth the struggle wasn't it! Wasn't it? Father can better relax in life, more evenings of drinks and mahjong; mother can begin, if she has not already begun, to find the right girl for the wedding, four or five years hence. (Mothers in Japan have marriage on the brain.) Success is pampered in Japan; the boy is heaped with praise and presents; chin high, banners flapping, he leaves for the university.

MR. NOBORU KATO is one of these lucky boys.

If for a year or two at the university these boys become a little derelict, it is because they suddenly feel completely free, free from home, free from the pressures of the PT Pushing Association, and free from all attendant disciplines. University discipline is relatively lax. Wonder-eyed in the beginning, they soon achieve a prankish courage. They feel like tweaking the behind of the Monster at the entrance, and the Monster from behind does look so harmless.

Noboru Kato is in, and that is all, nobody there cares. He and his classmates learn quickly what they have already heard: once in a university, easy out; failure is the exception, success is the rule; and once out, easy opportunity. The great temptation is to become lazy, even for Noboru, but some of his classmates yield more than he to the temptation. He goes in for sports; and furthermore he does not live in a bleak, unhomelike, wretched-barracks dormitory, but has found a small room in the home of a pleasant family.

The students' second year at the university will be just about the freest time in their youthful lives, the caper year; at least many will live it that way. Antichay; sports for the sportsmen (Noboru is doing judo); clubs; English Speaking Society; excursions into reading for the sake of reading, education for its own sake; and a certain number will indulge in student political demonstrations. (Student demonstrations, which in recent years have played a disturbing and noisy part of the life of the universities and in the national life, are an offensive form of outdoor sport. Noboru Kato maintains that true Japanese sportsmen will not take part in them. Most of the students who do are second-year students, and most of them are the ones who live in the bleak dormitories. Dormitory ennui and sophomoric antic-hay!) The second year capers to a close.

By the third year, university students begin to feel the growing pains of conservatism; even of responsibility; they buckle down, they study, and some of the disciplines which in the past were superimposed they begin to impose upon themselves; almost inevitably, and almost to a man. Then, by the fourth year, they are quite proper, nearly pious in the face of heaven soon to come. They look down with scorn upon the caper year, down upon demonstrating sophomores; and they feel the importance of education and of life. Something pretty fine has happened, something splendid.

Noboru is graduated. Many seniors, such as Noboru Kato, had known their future jobs before graduation. He has had to take an entrance examination to enter a trading company, but many of his classmates were offered good positions after a few interviews. Noboru steps out of the university and through the revolving door of Dai Nihon International Trading Co., Inc. Heaven! . . . Heaven may prove to be an unexciting place for those who have finally reached it. How often I have been told that it is dull. Noboru Kato may be bored but he is secure. The way up from there may not look like a ladder, only a slow ramp to a low horizon, but Noboru's parents are contented. His father thinks more about retiring; his mother thinks more about grandchildren.

Marriage first, of course. The girl has been selected for Noboru, and whether he accepts her or is permitted to select one on his own, in any event he will be married. Soon. Marriage, mating, and in due course a baby arrives.

Then Mr. and Mrs. Noboru Kato go right back down again to the bottom of the educational ladder, not as climbers but as pushers. Even those who had themselves fallen from the climb are eager to push their children up. Whether the Katos have three children, or five or seven, they may never know a year when they are not pushing some child up. It is a vicious ladder. Mr. and Mrs. Kato's children will have children and, in this land of eternal entrance examinations, grandparents are known to be among the greatest pushers of all.

A huge graduating class receiving degrees at Waseda's commencement.

Tokyo's Waseda University has a fineShakespeare Theatre and Drama Museum.

Waseda students training in karate.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

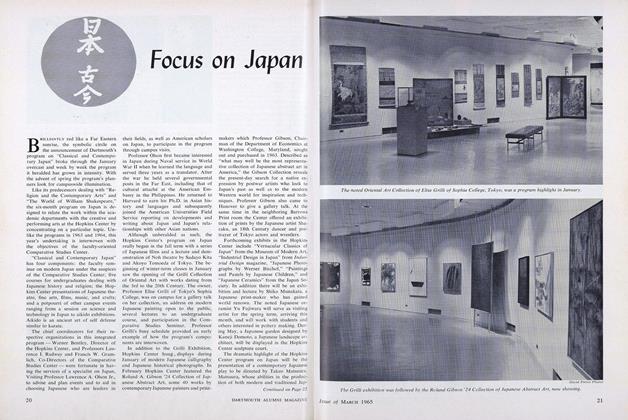

FeatureFocus on

March 1965 -

Feature

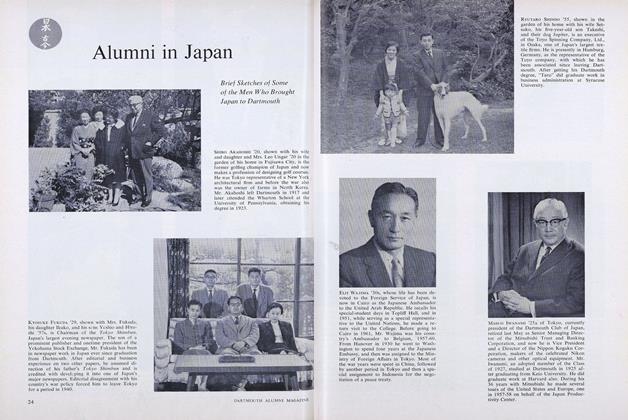

FeatureAlumni in Japan

March 1965 -

Feature

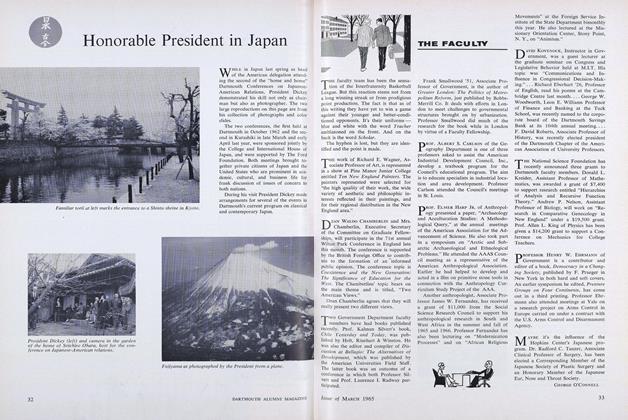

FeatureHonorable President in Japan

March 1965 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

March 1965 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HARRISON F. CONDON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1965 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, ALBERT W. FREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1965 By KENNETH W. WEEKS, EDWARD J. HANLON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCommencement '89

June 1989 -

Feature

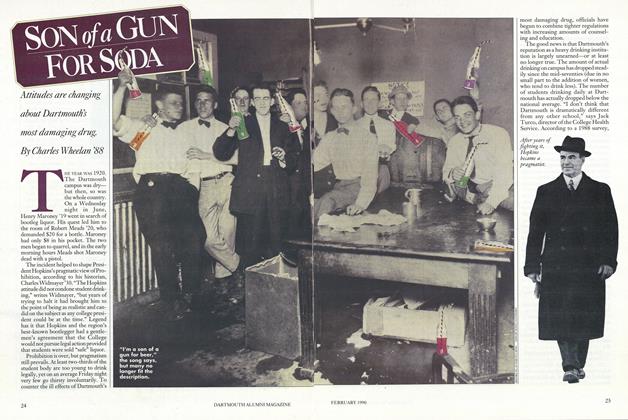

FeatureSon of a Gun for soda

FEBRUARY 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

COVER STORY

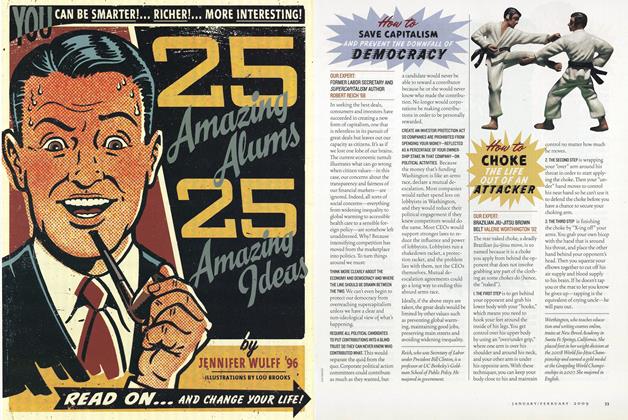

COVER STORY“Take This Advice Today!”

Jan/Feb 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureAnti-Bigot

JANUARY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureThe Dictionary's Function

May 1962 By PHILIP B. GOVE '22 -

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN