TO THE EDITOR:

Dartmouth graduates who have lain aside their history books may be interested in the appraisal of the second Earl of Dartmouth (William Legge) for whom the College is named, as it appears in the recent book The Boston Tea Party by Benjamin Woods Labaree, Associate Professor of History at William College (Oxford University Press, 1964).

Speaking of the period of relative calm from 1770 to the Boston Tea Party, December 16, 1773, Professor Labaree comments thus on the Earl of Dartmouth (pp. 82-83):

"Another encouraging sign from England was the resignation of Lord Hillsborough from his post as.. Secretary of State for the Colonies. Hillsborough had earned the enmity of virtually every American patriot during his four years in office, as much for his haughty attitude toward the colonists as for his preference for strong measures. Even Hillsborough's fellow ministers and the King himself soon tired of him, and he was replaced by the Earl of Dartmouth in August 1772.

"Dartmouth had had an unusual political background. Through the remarriage of his mother he became at the age of five the step-brother of Frederick, later Lord, North. Upon the death of his grandfather in 1750, he succeeded to the title Earl of Dartmouth, taking his seat in the House of Lords four years later. Dartmouth was not an active participant in public affairs, however, until the formation of the first Rockingham ministry in 1765. He then accepted the post of president of the Board of Trade with appointment also to the Privy Council. Dartmouth soon came to favor repeal of the Stamp Act, a stand that endeared him to the colonists, and he remained a Rockingham Whig at least until 1771. His devotion to Methodism gave him an" interest in common with many colonists. In 1767 Dartmouth became president of the board of Eleazar Wheelock's Indian Charity School at Lebanon, Connecticut. Two years later the institution was renamed in his honor when it was moved to Hanover, New Hampshire.

"Dartmouth's family ties with Lord North drew him away from the Rockinghamites and closer to the King's Friends in the second year of his step-brother's ministry, but his appointment as Secretary of State for the Colonies was nevertheless greeted with enthusiasm by most Americans. Dartmouth brought to the office an interest in the affairs of America and a courtesy toward its representatives rarely shown by his predecessor. In addition to his official contacts with agents in London, he carried on private correspondences with at least two important colonists, Thomas Cushing of Boston and Joseph Reed of Philadelphia. Franklin and other Americans in London felt welcome at his house and spent many pleasant hours in his company. In the Earl of Dartmouth the colonists seemed to have a friend in court."

However, after the Boston Tea Party the Earl of Dartmouth supported the Coercive Acts in the House of Lords, closing the Port of Boston, changing the Massachusetts Bay Charter, having the King appoint members of the Governor's Council, and changing the method of selecting jurors, limiting the Town Meet- ings, empowering the British commander-in-chief to quarter troops in unoccupied buildings in the towns. While some of these measures in the Coercive Acts were opposed by the Earl of Dartmouth, the query remains: If the College had been chartered in New Hampshire in 1776, instead of 1769, would it have been named for the Secretary of State for the Colonies, despite his generous contributions to the College?

Incidentally, the first ship to arrive in Boston Harbor with the ill-fated tea was named Dartmouth.

Professor Labaree's book is otherwise exceedingly interesting. He shows how the Boston Tea Party, a single act of defiance to the British Parliament, led directly to the Coercive Acts, to the Union of the Colonies in the Continental Congress of 1774, to the Revolution, and to American Independence. One wonders if the entire course of history might have been changed if Governor Thomas Hutchinson in Boston had permitted the ships to return to England with their tea, as they were permitted to do in New York City and Philadelphia.

Professor Labaree's book is highly recommended to students of American history in the Colonial period. Professor Labaree has done a vast amount of original research among the manuscripts, printed sources and newspapers of the time and his book is obviously a masterly summary of the available evidence.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE EDUCATION LADDER

March 1965 By PROF. BURTON E. MARTIN '33 -

Feature

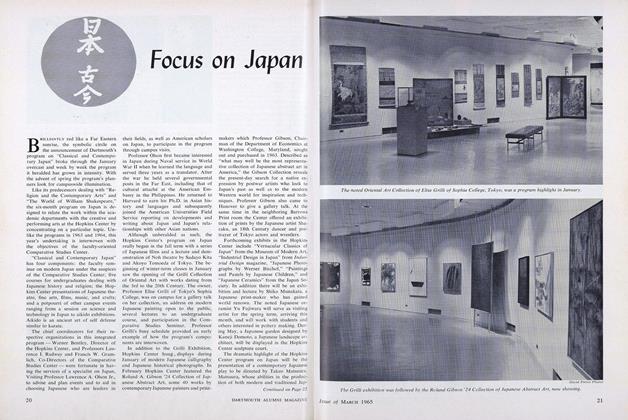

FeatureFocus on

March 1965 -

Feature

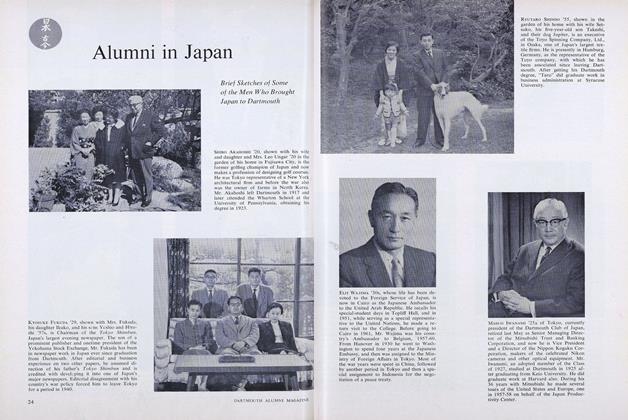

FeatureAlumni in Japan

March 1965 -

Feature

FeatureHonorable President in Japan

March 1965 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

March 1965 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HARRISON F. CONDON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

March 1965 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, ALBERT W. FREY

Article

-

Article

ArticleFORMER PASTORS OF COLLEGE CHURCH ACTIVE

March 1920 -

Article

ArticleTHE PLAYERS

April 1921 -

Article

ArticleFavor More Aid

February 1941 -

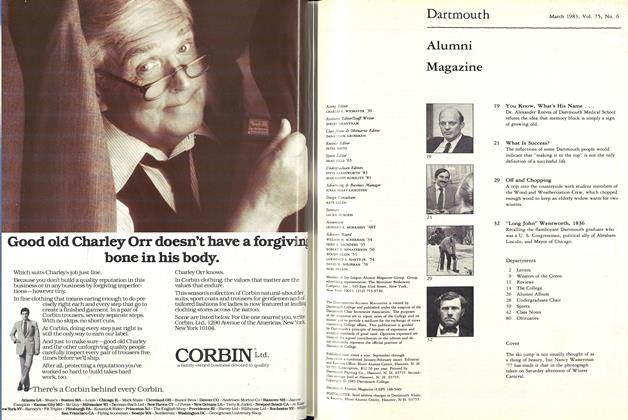

Article

ArticleMasthead

MARCH 1983 -

Article

ArticleFirst Daughter Of the College

December 1951 By A.P. -

Article

ArticleDiana Taylor, Act One: Gold Scissor Earrings

MAY 1997 By Heather McCatchen '87