Who Paid What

TO THE EDITOR

I hope the Winship-Ricklefs controversy continues in enough issues to get through to the professors of Hanover represented by I. E. Bender, Emeritus, those who are active, and some of the students.

In direct reply to Professor Bender, just who does he think excepting the servants of Mammon pay his salary?

So long as these letters are engaging in challenges, I challenge the Treasurer of Dartmouth College to break down the last twenty million dollars of endowment between the classifications of businessmen, teachers, ministers, journalists, physicians, and lawyers, and see who paid what.

And I would also like to remind Professor Bender that it was not too long ago that lawyers and doctors were considered businessmen rather than professional men in England. They created their own professional status. It was not accorded to them.

I can understand why businessmen are beginning to look more closely at the ultimate recipient of their generosity.

Cleveland, Ohio

The Moral Issue

TO THE EDITOR

The two letters in the March issue of the MAGAZINE, purportedly in defense of Dean Unsworth's controversial address, would appear to suggest that the Dean's opinions are either not open to or not worthy of discussion.

Professor Neusner makes the unquestioned points that (1) it is possible to dispute another's intellectual viewpoint without overtly questioning his moral values, and (2) that Dean Unsworth is a gentleman. On the basis of these matters of polite social behavior, he rules out discussion of the very subject of the Dean's address: moral values! Are all gentlemen free to dismiss the moral values of others without discussion?

Mr. Frothingham objects to the recent criticisms of Dean Unsworth's examples, as opposed to the meaning of his address. One might infer from this objection that the examples were poorly chosen. However, it is difficult to relate abstract ideas to reality, in the absence of valid concrete examples.

Mr. Frothingham points out the normal and healthy intellectual skepticism of most freshmen, and then follows a very curious line of reasoning: Since "old fashioned" morals are being questioned, let us simply deny their applicability, and substitute a "transitory" and more difficult ethical standard. Then, perhaps, the young people will somehow discover on their own the value of the old standards! Evidently, the "vanishing absolutes" can be intuitively recovered by the young, but are too difficult for adults!

The issue can be stated much more clearly than has been done: The moral values which form the very basis of our society are undergoing severe attack from several sides. This is a particularly serious situation, in view of our conflict with a society which adheres rigorously to a very rigid principle, diametrically opposed to our own. Our healthily skeptical and naturally confused young people need positive guidance in the practical application of our moral principles. They usually adopt as their own the principles of those whom they admire, those who have demonstrated achievement (in some cases, the principles of the street-gang leader).

If an admirably persuasive college faculty member states that he, too, questions our moral standards, the requisite guidance is absent. The blind lead the blind.

The whole mess seems to reflect an effort to justify widespread moral decadence, rather than than to undertake the more difficult task of fighting it.

West Chester, Pa.

Gaudet Tentamine Virtus

TO THE EDITOR:

To use a classical quotation in writing has long been an effective device, either to demonstrate one's erudition or to illustrate one's point. However, inexact use or translation of such a classical reference tends to blunt and impair the effectiveness of the writer's original aim or desire.

Every Dartmouth man has received recently literature concerning the 1965 Alumni Fund. In bold print Lord Dartmouth's motto, Gaudet Tentamine Virtus, is translated "Valor rejoices in contest." Alumni must have the courage to face squarely the struggle and strife of the challenge of the years ahead, so that Dartmouth College may meet its mounting annual operating costs. Id est - give your utmost support to the Fund!

But, let us look at that motto for a moment. Says Harper's Latin Dictionary, tentamine, the ablative of tentamen, means trial, essay, attempt. However, there is another Latin noun, certamen (whose ablative is cert amine), which means contest, struggle or strife. To translate tentamine as contest is not exact.

Dartmouth Alumni have no quarrel with the needs of the College. They will rise loyally to help her in the contest and struggle to meet these needs. But there may be a few alumni who might have preferred a finer translation of . the classics, particularly when employed in a brochure so widely disseminated.

Yours for purity,

Dallas, Texas

EDITOR'S NOTE: When questioned about Mr. Lyle's translation, Prof. Norman A. Doenges of Dartmouth's Classics Department had this comment to make:

"Robert Lyle's complaint about the translation of tentamine as 'contest' is more or less justified. He is correct that the proper classical Latin word for 'contest' is certamen. On the other hand, Latin mottos like that of the Earl of Dartmouth were meant to be understood in various ways. A strict translation of the motto, taking into account its late origin and the precise way in which tentamen is used in classical authors, would read, 'Virtue rejoices in temptation,' meaning perhaps that true moral worth welcomes trial so that it may be reconfirmed and strengthened. But temptation involves struggle, and virtus includes the concept of manly courage. Ergo gaudet tentamine virtus. Valor does rejoice in contest."

More on Teacher Education

TO THE EDITOR ;

The reaction to the Braden article in the December issue, as expressed by Ferry, Snyder, and Smith in the February issue, moves me to take Remington in paw for a word of caution to all hands.

Criticism of public education, and especially of the education of teachers, is fashionable and, to some extent, both justifiable and necessary. The educational establishment does indeed exist, as I am in a position to know, and needed the jarring it has been getting. It also needs to take the criticism more to heart than some of its members seem to be able to manage, if one can judge by their defensiveness to the gentle but telling accusations of, for instance, James Conant.

Although the saga of the California upheaval was interesting to read, it was written in highly slanted language and with considerable factual inaccuracy in some of its throwaway remarks. For instance, "in California, as in other states, it (a teaching credential, certificate, or license) is granted to those of good character who have completed certain course work at a university level. The requirements always stipulate a large number of education courses taught by doctors of education in schools of education" (emphasis added). This little passage, first of all, attributes to other states the real or alleged evils of California certification (or "credentialling," as they like to call it there). Some states may deserve such condemnation; others certainly do not. The ALUMNI MAGAZINE enjoys national readership; in some places the uneasiness resulting from a casual remark such as this is healthy; but in others it may stir up trouble where none is needed. Secondly, the statement about what is required for a teaching license is both false and inflammatory in context. Add to this a statement on the preceding page to the effect that the chances are the teacher who is teaching English in the local high school majored in education (about a one-in-twenty chance in Connecticut, if that) and a popular type of felonious assault on public education has once again been compounded.

Nevertheless, as a convicted educationist (although not a card-carrying member of the Establishment), I must confess to enjoying the tale of triumph of good over evil in California, while uttering a sotto voce "bravo" to the letter of Howard Snyder urging recognition of the fact that the California (or any other) State Board of Education can but make policy. It takes someone who knows a slow learner from a base on balls to get the job done.

Mr. Smith, in his piece, so well defended the "doctors of education" that he needs no help from me or anyone else. In doing so, however, he left a loophole through which the cohorts of the Council for Basic Education could drive a whole herd of Trojan horses. He points out at some length that we haven't yet learned what good teaching is, and therefore cannot identify with any sense of security who the good teachers are. On the other hand, we must teach the uninitiated how to teach well (whatever "well" is) and hence must require professional training. Some of us (including Conant) seem to detect an inconsistency here which we educators rarely manage to clarify. Yet it has been proved time and again that college graduates who have some professional training for teaching do, on the whole, a more acceptable job, whatever the criterion used, of teaching in the public schools than do those without such preparation. Sure, you and I can point to many exceptions, but they are just that - exceptions.

The editors themselves were guilty of a neat bit of slanting in the box on Page 24 of the December issue, headed "Dr. Conant's Reform Proposals." There were 27 actual proposals, covering several pages of Conant's book, which somebody presumed to summarize in one paragraph - a pretentious undertaking indeed! Those recommendations were meant to be taken in toto or not at all.

Of course, as with other criticisms of education, we educators have tended to drag our feet in clarifying the significance of Conant's findings and proposals, and to expend much time and energy screaming at each other in professional journals (wisely) unread by the public. As a matter of fact, we have a lot of trouble trying to explain anything to the public, since we persist, too many of us, in speaking or writing pedaguese to educated non-educators. Here, in my opinion, Mr. Braden is on mighty solid ground. I've even written a book on the subject (Guide to Pedaguese, Harper & Row). Educationists must learn to buck this language barrier if we are ever going to convince the taxpayers that we have anything to offer for their money.

Now (for those who have not already stolen home) that word of caution for which I have taken such a long windup: There are a lot of things wrong with public education and with the preparation of its teachers. Many of them stem from deep-rooted public apathy many decades old. That apathy, thank Heaven, is fast disappearing. Knights on white chargers are coursing about the countryside slaying the dragons of pedagogia. Unfortunately, some of them are not quite sure what a dragon looks like, never having met one, and are a bit too quick to pin the label on everything that moves and breathes and is guilty of a doctorate in education. They would be surprised, I suspect, to learn how many of their victims have themselves a few dragons to their credit.

We have our share of asses in education - perhaps more than our share - however slow we have been to admit it. And those of us who claim not to be asses have been reluctant to confess publicly the sins to which we privately plead guilty. Only when we do is the public likely to believe us when we suggest that maybe there is a bit of good somewhere in what we are trying to accomplish.

The good citizens who would improve public education must stay interested; but they must also be a bit more discriminating and less quick on the trigger. We educationists must, if we are to be credited with any virtue at all, be less defensive and more realistic and understanding in appraising our critics. Not all of them are idiots. Nor, let us hope, are all of us.

Mr. LeSure is Consultant in Teacher Certification for the Connecticut State Department of Education, meaning, he writes, that"I run that bureaucratic part of the show,and have since 1954." A review of his book, Guide to Pedaguese, appears in this issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

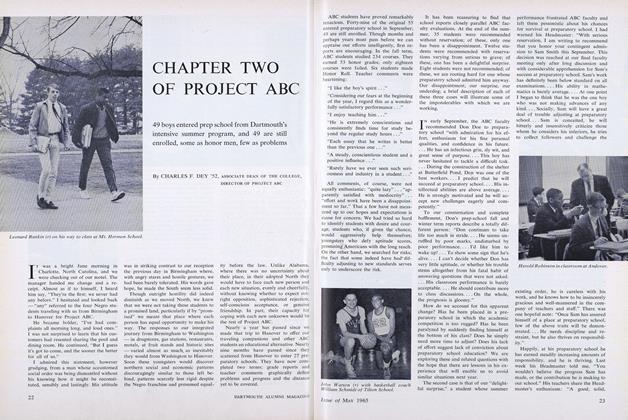

FeatureCHAPTER TWO OF PROJECT ABC

May 1965 By CHARLES F. DEY '52, -

Feature

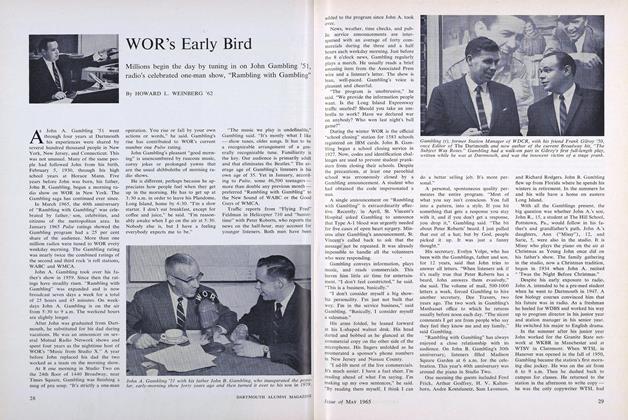

FeatureWOR's Early Bird

May 1965 By HOWARD L. WEINBERG '62 -

Feature

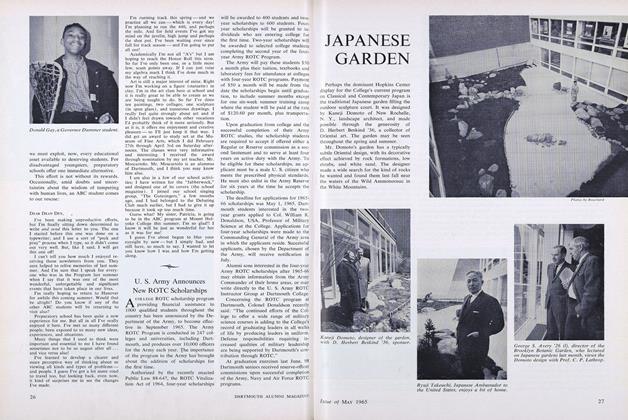

FeatureALUMNI COLLEGE '65

May 1965 -

Feature

FeatureJAPANESE GARDEN

May 1965 -

Article

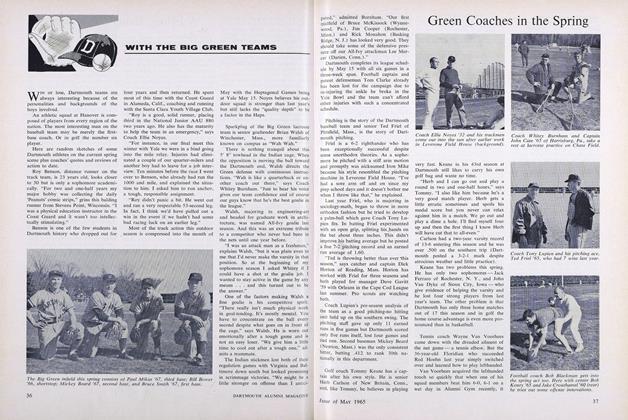

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

May 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

May 1965 By ROBERT W. MACMILLEN, ROBERT H. LAKE

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

February 1919 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorChief Justice Chase

June 1936 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

February 1953 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

January 1957 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

October 1960 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorGo (Small But There Are Those Love It) Green!

JANUARY 1997