ByProf. Frank Smallwood '51. New York:The Bobbs-Merrill Co., Inc., 1965. 324pp. $6.00 (paperback $2.95).

This is quite a remarkable book. As an old England hand with three years residence and work in London during the past 25 years, I was surprised, chagrined, and charmed by everything that Frank Smallwood could tell me about that fascinating metropolis. He has given students of comparative government and literate adults an incisive (highly-researched) account of the birth pangs of that quasi-metro government, the Greater London Council, which was created by the British Parliament through the Greater London Act of 1963.

This act, by the way, barely squeaked through under Tory rule and would have probably failed if Christine Keeler had toppled the once "mighty Mac." Quasi-metro government is used advisedly since this English experiment - watched by puzzled local government experts the world over - merely gives four main powers only to this new tier of rule for a defined area of 630-plus square miles: (1) over-all traffic control, (2) general planning authority, (3) housing developments outside the area, (4) general housekeeping services including parks and open spaces. Obviously a significant number of normal local government functions were excluded — for example: education, which after a hard fight, was left essentially in an expanded London Country Council system.

Smallwood's analysis is neatly couched in a sensitive appraisal of the English/London milieu, which ranges through history to urban renewal; considerable empathy is evidenced for the British way-of-life. The theory structuring the research and book is taken from Gabriel Almond's "input-output" model of systems research which employs four input functions: (1) social foundations of attitudes, (2) interest groups, (3) political groupings, (4) informed public opinion and mass media; and three output functions: (1) legislative enactments, (2) executive functions and (3) judicial functions. In short, Smallwood goes over the London story with a theoretical fine-toothed comb marshalling evidence on what went into the cobbling together of the final act after all the complex motivations of various interests had worried the initial proposals put forth by the Royal Commission, answerable to the British National Government.

Which points up the basic difference between the English scene and our harrying problem of how to govern 216 Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas in the U.S.A. with archaic splintered and overlapping jurisdictions! The London Act was settled by parliament not by the vagaries of popular plebiscite; it might be nice for us to have a similar national government able to act in internal affairs as it most certainly is by all immediate evidence in external affairs. If the growth of government is an evolutionary process — we may have here a sport of promise in the London plan. In any case, Smallwood's effort will be widely used, quoted and already serves as a sturdy addition to the understanding needed by man to govern himself in the 20th Century megalopolitan society.

Professor of Sociology

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStudents and Commitment in the Deep South

June 1965 By BERNARD E. SEGAL '55, -

Feature

FeatureTHE SUBJECT IS GILROY

June 1965 By RAYMOND BUCK '52 -

Feature

FeatureSocial and Moral Responsibility in the Modern Corporation

June 1965 By RODMAN C. ROCKEFELLER '54 -

Feature

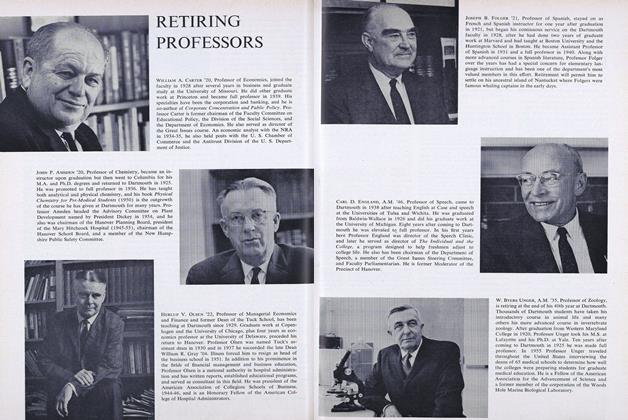

FeatureRETIRING PROFESSORS

June 1965 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65

H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31

-

Books

BooksTHE RUSSIANS IN FOCUS

October 1953 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN EUROPE.

March 1955 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Books

BooksADVENTURES OF A SLUM FIGHTER.

January 1956 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Books

BooksCOMMUNITY PLANNING.

December 1956 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Feature

FeatureA CITY VOICE CRYING IN THE WILDERNESS

JUNE 1963 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31 -

Books

BooksMONUMENTAL WASHINGTON: THE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE CAPITAL CENTER.

JANUARY 1968 By H. WENTWORTH ELDREDGE '31

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

December 1916 -

Books

Booksshelflife

May/June 2011 -

Books

BooksThe President's Secret

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Charles M. Wiltse -

Books

BooksTime and the Rivers

March 1979 By Dan Nelson '75 -

Books

BooksSplendor

MARCH, 1928 By H. B. Preston '05 -

Books

BooksTHE STRUCTURE OF THE DEFENSE MARKET

MARCH 1968 By MARTIN L. LINDAHL '40h