Social and Moral Responsibility in the Modern Corporation

JUNE 1965 RODMAN C. ROCKEFELLER '54Mr. Rockefeller's article is based onhis lecture to the Great Issues course,April 26, and with only minor changeappears here just as he prepared it fordelivery. His talk was one of five givenby guest lecturers during the spring termon the general theme of "Ethics inAmerican Society." Other speakers dealtwith the humanistic and religious sourcesof ethics and with the role of ethics insocial action and in politics.

THE Chase Manhattan Bank's semimonthly economic review Businessin Brief stated in the lead paragraph of the March 1965 issue: "Business was very good during the first quarter. Industrial production ran more than 7% ahead of a year earlier. ... Corporate earnings appear to have been better than expected. Employment and weekly earnings continue to advance."

There is a sense of satisfaction with a job well done, a feeling of well-being which permeates industry and most of our economy today. It is an important aspect of the setting for our discussion tonight. Business in 1965 is doing a good job; indeed, we have seen 50 months of continuous growth in sales, earnings, payrolls, and capital investment.

Yet we also sense a disquiet, a questioning of the role of business and of the performance of private enterprise in a world increasingly concerned with human suffering, the establishment of social justice, and the elimination of privilege. Professor John Galbraith in his book The Affluent Society raises serious moral questions about the entire orientation of our economy toward production. More and more society is calling our corporate leaders to justify their behavior, their performance, and their privileges.

It was perhaps accidental that the two illustrations of confused ethical behavior which Dean Unsworth of the Tucker Foundation used in his now famous address to the freshman class [published in the December 1964 issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE] were selected from the business world. However, it seems clear that the greater intellectual confusion over the role of ethics and morals is very much with us, not only here tonight, but throughout the country.

As a vice president of my company, I am almost as conscious as you are of the meaning of spring to members of the Senior Class. You are very conscious of the next step in your lives, for some graduate school or the military, for some a job. My company and I personally have been seeing you and your contemporaries for the last few months in interviews and discussions. It is fascinating to me to note the degree to which a thread runs through all these meetings - you want a future which will satisfy your urge to be of service - can you hope to realize it by working in business? Salary is important, but at this moment in your life the awful responsibility for your salvation looms before you, and that motivation shines through with great clarity. This then is the other half of the setting for our discussion tonight.

When we talk about business in this discussion of morals and ethics, we are talking about the corporation. To an amazing degree, the corporation has come to dominate our economic life. We find that farms are now incorporated, that taxis are invariably owned by a corporation, that proprietorships and partnerships as vehicles for business are clumsy, inflexible, and are being discarded.

The corporation is a legal vehicle to enable people, called stockholders, to join together through their limited money investment to enter into some hopefully profitable activity. It is an easy means to gather capital, yet limit the liability of those providing it. This is done by setting up as an independent legal entity the corporation, for whose actions the stockholders have no responsibility beyond their investment. The stockholders can run the corporation themselves, or turn it over to paid managers, who need not have any ownership. As Adolf Berle has been pointing out since his magnificent book Modern Corporation and PrivateProperty came into public knowledge in 1932, the divorce between ownership (the stockholders) and managership (the management) has become ever more prevalent. As corporations grow, with their stock more widely held and their business activities more complex, this change is inevitable. Today, when you consider a job with business, you are considering it in a corporate management, and possible future ownership is usually considered only as a means of additional remuneration.

It was as a representative of management that Roger Blough, Chairman of the Board of U. S. Steel, spoke in the October 1963 conference which touched on the role of the U. S. Steel Corporation in mediating the racial conflict and violence which shook Birmingham, Alabama, during 1963. Mr. Blough was faced with a moral issue - what should U. S. Steel do about race relations in Birmingham, in its role as the largest economic power in that community? The question restated could be: does a corporation, and its management which directs it, have any moral responsibility towards the community? Is a corporation a member of society or is it solely an amoral economic machine created to turn out wealth?

AT this point I would like to step back from Birmingham to look at Mr. Roger Blough's company, the U. S. Steel Corporation, the world's largest private producer of steel and steel products. Looking at the 1964 Annual Report, we find that U. S. Steel had sales last year of $4,129,400,000, which produced $236,785,000 in net profits. The company employed 200,000 who received $1,795,000,000, while $133,500,000 in dividends was paid out to the 368,800 stockholders. An additional $1,404,000,000 was paid to suppliers and others who were dependent on U. S. Steel's purchases for a part of their sales. This is the company which Mr. Blough and his management associates run, and from the look of things they run it quite well.

But for what purpose is Mr. Blough running the U. S. Steel Corporation? Who gives him guidance? Who gives him and his associates the right to direct this enormous vehicle of private power? Why should Mr. Blough be the one to decide what role his corporation will play in Birmingham or in price setting or in wage disputes? He doesn't own it, why does he run it?

Classic economic theory, and indeed the fairly commonly accepted version of the procedure whereby Mr. Blough receives his legitimate authority, runs somewhat like this: the stockholders meet annually and as owners of the corporation elect representatives to serve as directors. The directors then act as charged by the stockholders and elect the officers, including the chairman of the board and the president. Thus the stockholder owners directly place into management's hands the authority to run their property for them. If the owners don't like the way it is run, they can meet and elect another board which will do their bidding.

This concept worked well in the 19th and early 20th centuries when corporate stockholders were active capitalists in daily contact with their managements. Today it still works well in a few cases where a few individuals or a family controls the stock, and assumes responsibility for the management. However, in the vast majority of the large and mediumsized corporations, the stockholders have become a form of silent contingent bond-holders, busy with their own lives and affairs, whose sole reaction when displeased with corporate management is to sell their shares. Thirty-five years ago Mr. Berle clearly spotted this trend. Ownership' of the passive property - stocks and bonds - has separated from ownership of the active assets - the corporation's cash, plant, equipment, and good will. This trend continues and is inevitable.

Mr. Blough undoubtedly has a sincere concern for the welfare of his stockholders, and sincerely thinks he is running the company for them. However, I doubt that he greatly fears their wrath, and I should imagine that his being personally accountable to them enters his head only on a theoretical basis. Mr. Blough proposes the members of the board to a stockholder body whose proxies he is virtually assured of. He then proposes to the board, the members of which he has just elected through controlling the proxies, the officers he wants elected to run the company. Lastly, he proposes to his board the name of the man he wants as successor when he retires. Management of U. S. Steel and most other large corporations is as autonomous as if they had gone to the stock market and bought up all their shares. Yet, management still tends to maintain that the corporation is the stockholders and that they are fiduciaries handling the stockholders' money. This attitude need not be bad in itself, and indeed breeds a high sense of responsibility, but to a narrow purpose, increasingly at variance with current circumstances.

TOUCHING again on Birmingham, we begin to see more clearly the reasons for Mr. Blough's point of view. Let us make clear that we are not attempting to criticize Mr. Blough or pass judgment on the corporation's actions (or lack thereof). Rather, we are looking for reasons. If Mr. Blough felt himself to be responsible primarily to the stockholders, then his reasoning might well have been as follows: this racial violence is deplorable, and, as individual citizens, the management of my subsidiary, Tennessee Coal and Iron, should look to their consciences as to what to do about it. However, we are running the corporation for the benefit of the stockholders, and as such we have no role to play in that civic, political and social matter, unless it gets so bad it affects the plant's operations or otherwise endangers profits. Given the basic assumptions of corporate management responsibility, plus the natural reluctance of all Americans to having large corporations play God, it is rather hard to be too critical of Mr. Blough's feelings and actions.

It seems to me that what has happened is that American corporations are struggling to handle 20th century problems with 19th century theories. More and more they are running into the necessity of rethinking the role of the management and the role of the corporation in the society in which they find themselves. Both in this country and abroad, serious questions have been raised about the right of private property to precede social justice. If the owners of the private property are foreigners, as is happening more often with U. S. corporations' active foreign investment pro- grams, the emotional impact of nationalism is added to the equation.

Needless to say, many laws have been passed to govern the behavior and performance of corporations. Almost all of these have been fought by corporate management as infringements on private property and on the right of management to operate as they see fit. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, in the last thirty years since the Depression corporate practice has greatly changed. Many corporations are outstanding civic leaders, indeed much of our private philanthropy is corporate today. Many presidents and other corporate leaders have voiced their beliefs in the multilateral nature of their responsibility.

However, the fact remains that the basic theories of the corporation remain as they were in 1900 when men of wealth were convinced they were doing God's will in making money. The level to which this self-confidence rose can be judged by this quote from George F. Baer, a railroad president who stated during a coal strike in 1902: "The rights of the laboring man will be protected and cared for, not by labor agitators but by the Christian men to whom God, in his infinite wisdom, has given control of the property interests of the country."

I feel it is urgent that we break out of this intellectual trap. For too long we have suffered from the inherent dangers of moral ambivalence in our national thinking on business. We ask the cream of our nation's organizational and managerial talent to live in a climate of an unresolved moral issue. This issue is not theoretical but, rather, very practical. As businessmen, do the commonly understood moral and ethic traditions of our Judaeo-Christian heritage apply, or does the role of the corporation demand that the executive attempt to live a moral Dr. Jeky 11 and Mr. Hyde duality? Putting it another way, is there such a thing as an ethical heritage for business, and if so, how is it different from our total heritage?

If you think this is an intellectual game, listen to the testimony of one of the GE executives convicted in the 1960 electrical monopoly conspiracy, as quoted in Fortune, April 1961: "We did feel that this was the only way to reach part of our goals as managers. . . .We couldn't accomplish a greater percentage of net profit to sales without getting together with the competitors."

I WOULD like to spend the rest of this evening's talk exploring with you what I hope can be a more satisfactory total theory of the facts, the motivations, and the benefits we experience from business today. I hope this may help you in your career. I think it will help those of us, the vast majority of corporate executives, who are trying to run a company, make money, and feel that we have contributed to the society in which we live.

Frank W. Abrams, retired Board Chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey, stated in 1954: "The job of professional management is to conduct the affairs of the enterprise in such a way as to maintain an equitable and workable balance among the claims of the various directly interested groups - stockholders, employees, customers, and the public-at-large."

This approach has brought howls from the classically oriented economists and from those businessmen who fear it may lead to further restrictions on their freedom of action. However, let us examine it for a moment. Mr. Abrams talks of the claims of the interested parties - against what do they have legitimate claims?

Let us look at Mr. Blough's company again; we see that it is the sales dollars they are carving up. The traditional pie chart clearly shows how the 1964 U. S. Steel sales dollar was divided - 200,000 employees got 43%, by far the largest share, followed by suppliers who received 34% for a total of 77% of the corporate sales effort. By comparison, the stockholder owners received dividends equalling 3.2%, and the corporation retained 10% for itself through depreciation and retained earnings. Society, as a whole, in the form of government, received 8%, paid as taxes. Basic to the entire process, the customers received service in the form of steel and steel products for which they were willing to pay a total of $4,129,000,000. This system works well, freely, and with relatively little government interference. It works well despite the fact that our commonly held theories of how it works are almost totally out of date.

I think we will all accept the fact that the corporation, through its management, is responsible for the initiative and organizational ability that produced the coordinated effort which produced the sales. Mr. Abrams looks at this role as a sort of private government function, in which the corporation takes charge of private assets, labor, plant, materials and time, and produces a good which is sold to the mutual benefit of all concerned. In the process, it exercises substantial power over other people's lives and property.

If we accept this theory, and it is a fairly accurate picture of what actually happens, we can begin to approach a new justification for our managerial function which is ever so much broader than tying it strictly to stockholders. It also happens to correspond more directly to the facts.

John Locke, in his essay On CivicGovernment, laid the groundwork in the 17th century for all our democratic political principles, in the famous statement: "All governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed." In the business sense, who is being governed, who is it that must give their consent to establish the just powers of this private government? Those dependent on the corporation, those dividing up the sales dollar, are those who must consent. If you accept the management as a form of private governmental power whose existence is essentially beneficial to those governed, you describe the role of management and the corporation in a new way. You create a position of dignity for management based not on property rights but on a job well done. This job is done for labor, other business, consumers, the stockholders, and for the society generally, all of whom submit to control over a part of their freedom in return for the benefits. The dynamics of this job are the changing terms of the consent of the governed, and the evolving demands of our modern economy. Cooperation is the key to this consent, and the cooperative nature of our economic society begins to emerge in its true light.

I WOULD like to go further with these thoughts. We have not considered under what terms the society will consent to this private power, the moral aspects of the private governmental agreement, nor that all-pervading essential question, the role of profits.

Three years ago I wanted to form a corporation in Argentina to build middleincome housing. Unfortunately, the corporation was formed but the houses were never built, as the government fell in the meantime. However, in the course of the formation of the corporation, a fact was brought home to me which bears on our thoughts here. Argentine law, which is the expression of their society, will not let a group of less than, I believe, five persons form a corporation, because the independent juridical personality of the corporation is not needed if only four want to come together. The Argentinians, not yet exposed to the uses of the corporate body to which we are accustomed, see more clearly the separate personality of the corporation.

Society grants to this separate, permanent, independent legal person most of the rights of natural persons — to hold property, to enter into contracts, to sue and be sued, and to produce and sell, under a great range of freedom. Our society cedes to these private legal personalities, the corporations, the control over most of the nation's means of production, on which we directly depend for our welfare. We have already agreed that these corporations in most cases have long since slipped out of the control of their stockholders and are for all intents and purposes independent entities. Given this set of conditions, I would imagine that the society would be somewhat concerned as to how its creations behaved with their rather large power.

Now we are face to face with the central question of tonight, the issue of the moral and ethical content of business, the question of the existence of an ethical heritage for free enterprise.

We all intensely believe in freedom in this country, and we say we are ready to die for it. What is the nature of that freedom which we hold so precious? I would like to quote from another Great Issues speaker who nine years ago dealt with some of these same questions we are struggling with tonight. Mr. J. Irwin Miller, Chairman of the Board of the Cummins Engine Co. of Columbus, Indiana, defined freedom as follows: "Freedom, if it has validity, means not my freedom, but an awareness and a sensitive concern for the freedom of the other fellow."

Behind the thunder of the civil rights movement, of the politicians' speeches, and of the newspaper headlines, lies the unspoken agreement of Americans that in order to insure their individual freedoms, they will observe others' freedoms. All our national struggle in civil rights boils down to the demand that White Americans agree to respect the freedoms of Negro Americans. Thus freedom is a compact, a two-way agreement of consent to mutual respect. We have the moral essence of this very clearly in that most beautiful of all rules, the Golden Rule: "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you."

In such circumstances, how can we exempt the corporations of this country from similar responsibilities? We clearly see they are independent, legally separate personalities who control their own destinies. They are responsible in practice to the law of the society, but their only tie to their natural stockholders has become almost totally theoretical. Therefore, they .must undertake the responsibilities of free participants in our society.

It might have been possible before to argue that corporations had no personality, that they were but an extension of the property rights of their owner stockholders. Not so today, as they are free participants in our society. The property rights in question today are those of the active property of the separate corporate persons, not the passive stocks of the owners. Pope John XXIII, in his historic Encyclical Letter Mater et Magistra, clearly establishes the role of this right of property: .. in the right of private property there is rooted a social responsibility ... the over-all supply of goods is assigned first of all that all men may lead a decent life."

Thus we return to the doctrine of mutual consent that freedom is a compact between men to refrain from so behaving as to destroy each other's freedom. Applied within the corporation, we see that all the forces necessary for the continuation of the corporation's function - labor, capital and management - are in a compact of mutual consent to so act as to respect each other's minimum freedoms. Management is at the center of this compact and its success depends on its abilities to maintain the compact.

The corporation is also in a compact with the society which created it. The society, which recognizes the corporation's right to private property, will tolerate the private ownership and use of the means of production so long as the corporation produces the minimum socially and economically needed good. This good is economic in that it builds the total wealth of the society and it is social in that the wealth produced has as its purpose the building of a better life for all the individual citizens.

This compact is not only a responsibility, it is a freedom and the basis upon which free men can come together to do great good. For too long we have hidden the light of the dynamic power of our free enterprise system to create good, social and economic good, under the bushel of our obsolete theories of business. For too long we have fed ammunition to our enemies, the prophets of class warfare, by insisting on the selfish motivations of antagonistic classical capitalism, rather than preaching the proven success of our mutual consent, cooperative free enterprise system.

MONETARY profits have played a prominent role in defining classic capitalism, and remain essential today to the proper working of the free enterprise system. Can we reconcile profits to this doctrine of mutual consent?

Profits are the reward to the corporation for its successful participation in this compact. In the dividing up of the sales dollar the managerial function, the function of imaginative risk taking, leadership and organization, takes the last share. This is the most risky share but it has the great reward of being potentially unlimited. The profit does not come out of the sweat of the worker, the exploitation of others' labor, but comes from the act of creating something which was not there before: the economic and social good represented by the willingness of the customer to buy. It is the society's agreed-upon reward for a job well done and is a monetary method of measuring how well done. Obviously, there can be exploitative profits, monopoly profits, and illegal profits which deny this compact, but in our country, anyway, society has a way of putting an end to these violations very quickly. The discipline and reward of profits are essential to the proper working of our business system. Without profits there will be no business system.

We here tonight have affirmed that our business has a moral content, that free enterprise has an ethical heritage. We are confident that the future of your jobs in management and mine is not com- promised with ethical ambivalence and confusion. In this country, we are in the process of evolving a business philosophy which is based on long-range considerations, high sales volume, low markup principles, and which consciously expresses its sense of community responsibility and social awareness.

Out of this evolution can come a new definition of free enterprise, a definition which confidently states that free enterprise is the vehicle for social progress which, more than any system ever devised, can produce the most good for the most people. It can say that free men consent to free enterprise because free enterprise gives to them much more than it takes. The deeply felt motivations you hold to be of service to your fellow men must not be, and are not, in conflict with our fundamental economic system. It, too, is based on service to our fellow men.

Undergraduate "bookers" in the May sun.

THE AUTHOR: Rodman C. Rockefeller '54, oldest son of New York's Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller '30, is a vice president of the International Basic Economy Corporation (IBEC) and has charge of its Housing Division, which builds mass-production housing in Puerto Rico, Chile, and Peru. Upon graduating from Dartmouth with Phi Beta Kappa rank in 1954 he entered Army service as a second lieutenant in the Ordnance Corps and spent most of his two years of duty in Germany. After a year of graduate study at Columbia Business School, he joined American Overseas Finance Company, an IBEC subsidiary, and had responsibility for international loans and investments. He is now a director of IBEC and of Rockefeller Center, Inc., and is a co-chairman of the Interracial Council for Business Opportunity. He is an officer or director of a number of foundations, civic and cultural organizations, and inter-American groups. He speaks fluent Spanish, travels widely in Latin America, and has been awarded Chile's Order of Merit. Mr. Rockefeller resides in New York City with his wife, the former Barbara Ann Olsen, and their four children.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStudents and Commitment in the Deep South

June 1965 By BERNARD E. SEGAL '55, -

Feature

FeatureTHE SUBJECT IS GILROY

June 1965 By RAYMOND BUCK '52 -

Feature

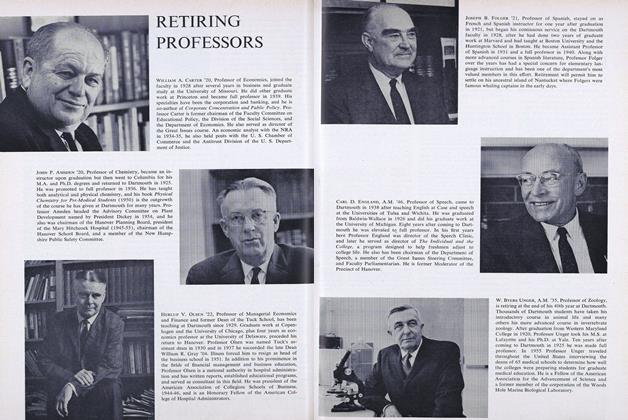

FeatureRETIRING PROFESSORS

June 1965 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

June 1965 By ERNIE ROBERTS -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

June 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

June 1965 By GEORGE H. MACOMBER, JOHN S. MAYER

RODMAN C. ROCKEFELLER '54

Features

-

Feature

Feature"Doggie" Julian, Master Coach

JULY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Vote to Consider Associated School for Women

MAY 1971 -

Feature

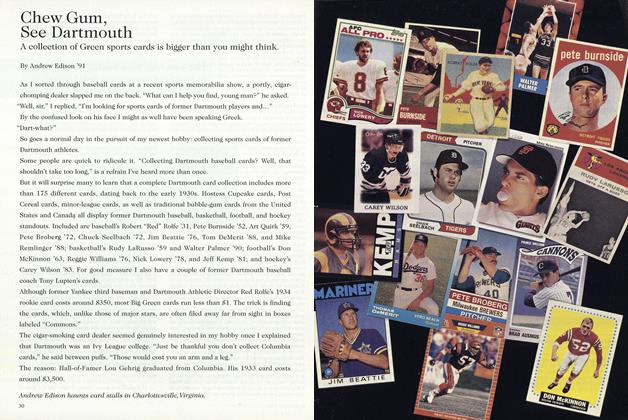

FeatureChew Gum, See Dartmouth

NOVEMBER 1993 By Andrew Edison '91 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORY“Out of Crisis Comes Opportunity”

MAY | JUNE 2016 By ANDREW FAUGHT -

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

NOVEMBER 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWelcoming the Loner

SEPTEMBER 1988 By Victor F. Zonana '75