From: Stephen BurroughsTo: The Students Subject: Making a Living

Stephen Burroughs, son of EdenBurroughs, a Trustee for 40 years, isreputed to have spent more time in morejails than any other 19 th centuryAmerican.

IT has lately come to me out here in the Great Rogues Gallery that there is troubling my alma mater today the question of what an education should be. Of practicality and of pelf? Or of philosophy and of principle? Should one in short, dear sirs and madams, prepare oneself narrowly with a close and constrained end in view, or should one range far and wide in the country of culture, seeking the Golconda of the mind here, the Kohinoor of the spirit there?

As one who has had, may I be permitted a mild boast, a small taste of varied employment since quitting the Hanover Plain, and a wider experience of the fickle nature of humankind, I may therefore shed some useful light and not a little hard experience on the subject. As one whose father was both a Hanover minister and a long-time Dartmouth Trustee, I early knew the pathways and the practices of the righteous. As a prisoner on Boston's Castle Island, I later knew the lash and the legirons and the lengths to which the righteous will go to thwart a man who is merely trying to provide for himself and his family.

"One of the benefits of a college education," Mr. Emerson has said, "is to show the boy its little avail."

When I was a student at Hanover (Class of 1785), I thought this was so, being hounded by a teacher - it was ever my fate to be pursued by some human Fury - until I found it to little avail to continue as a pupil. Others before me and after me have early shaken the dust of Hanover from their heels - Mr. Ledyard and Mr. Frost are two that come to mind - and while my fame was not exactly of the specifications of theirs, I was not unknown in my day.

What, I wonder, did they carve on my tombstone, so many years after my notoriety, up there in Three Rivers, P.Q.? Stephen Burroughs . . . what? Schoolteacher? Minister? Dealer in coins (albeit brummagem ones)? Doctor? Land speculator? I was all of these, and a few others that men (and women) of mean minds unjustly accused me of: liar, cheat, counterfeiter and, most preposterous of all, attempted rapist.

This last I was convicted of, but the charge was that I had attempted rape on horseback, with the girl riding before me on the steed! As a contemporary of mine remarked, this was "quite original in the manner of the offence" and that "if he had succeeded, the world might well say, he had fairly outquixoted Don Quixote himself."

But Mr. Emerson is, if I may be so bold, wrong as to the benefits of a college education. My education, however truncated, gave me that breadth of mind and quickness of invention to become a minister, though dressed in a light gray coat with silver buttons, green vest, and red velvet breeches. It is true that on this occasion I was helped no little by the knowledge that I had borrowed some of my father's sermons. But is that not the mark of the liberally educated man, to have the intellectual baggage handily about him to serve well on any trip, temporal or spiritual? I was able to serve as doctor aboard a packet bound for France by "obtaining the assistance, advice and direction of an old practicioner in physic." Is it not the mark of an educated man in the 20th century, as well as in the 18th, to seek the proper founts of knowledge?

Sent to jail for counterfeiting because I would not say from whom I had innocently gotten the spurious coin, I soon found that close confinement brought upon me fits of blackest depression. In one of these, I set fire to the jail, hoping to perish thereby and only got, in the bargain, the base appellation of jail-breaker.

'Tis true, later, shunted from jail to jail, I did try to tunnel out of one and fled by boat from Castle Island's prison only to be recaptured in a Dorchester haymow (haymows were troublesome to me - the Pelhamites, once my ministerial flock, nearly caught me in another). But what man, trained in the freedom of the mind and in the liberality of the arts and sciences, can long suffer the injustice of fetters?

These incidents, you may be sure, made the name of Stephen Burroughs well known along the Atlantic seaboard. Imitation, they say, is the sincerest flattery and I soon had more than my share of flatterers. Any knave wishing to try counterfeiting, forgery, or any number of base crimes called himself Stephen Burroughs and I accumulated an impressive, but unwarranted, list of malfeasances.

Indeed, after I had long removed to Canada and engaged in business and school-teaching there, it was regularly reported that I was "assiduously employed in counterfeiting bills of the various banks of the United States" and that (falsely) I had been in prison in Montreal and Quebec.

On measure, mine was not a prosy life, but I should not have wanted it so. I ranged far and wide, both geographically (from Georgia to Canada) and metaphysically (from the strict Presbyterians of Pelham, Massachusetts, to my own Catholicism in Three Rivers). In my memoirs I put it that the good of society may be obtained by "a supply of food for the mental part of creation; for the mental part requires a certain supply, in order to render us sensibly happy, as well as the corporeal."

For the rest, I would say, with Dryden, "Trust nature, do not labor to be dull."

Captured in the haymow —from the Life of the Notorious Stephen Burroughs.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBeating the Odds

May 1975 By IRVING H. LEVITAS, M.D. -

Feature

FeatureBlack in the White Academy

May 1975 By WARNER R.TRAYNHAM -

Feature

FeatureRalph Sterner: See-er

May 1975 By RALPH STEINER -

Article

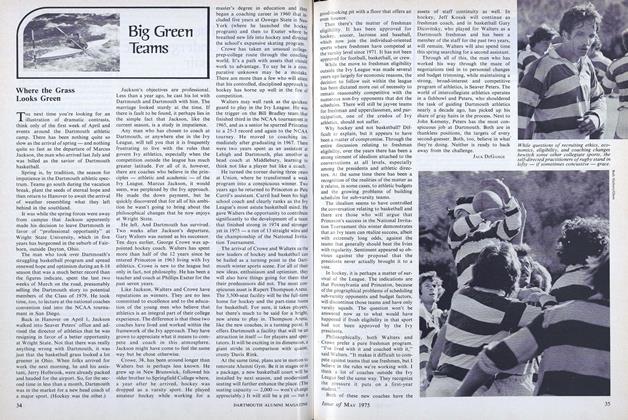

ArticleWhere the Grass Looks Green

May 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

May 1975 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., HARTHON I. MUNSON -

Article

ArticleThe Long Walk

May 1975 By OLIVE TARDIFF

JAMES L. FARLEY '42

-

Article

ArticleThe Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

May 1976 By Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

April 1942 By James L. Farley '42 -

Article

ArticleFull-Fledged Commencement Returns

August 1946 By James L. Farley '42 -

Article

ArticleWar Story of Jiggs Donahue '15

November 1946 By James L. Farley '42 -

Feature

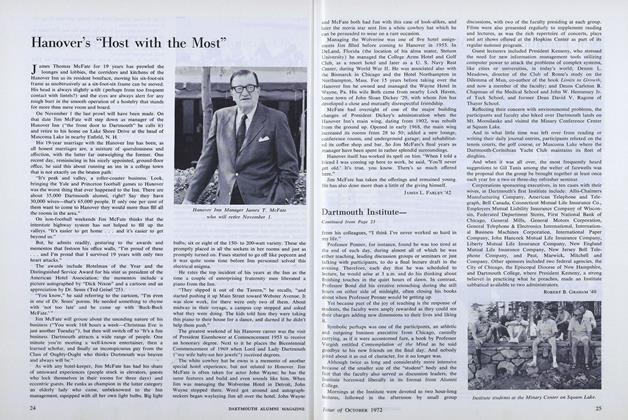

FeatureHanover's "Host with the Most"

OCTOBER 1972 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

MARCH 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42

Features

-

Feature

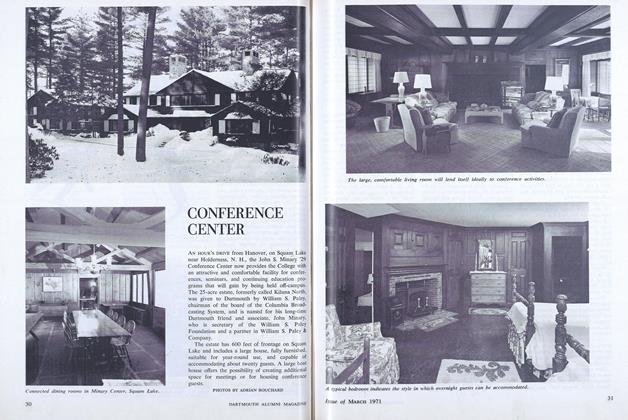

FeatureCONFERENCE CENTER

MARCH 1971 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Vote to Consider Associated School for Women

MAY 1971 -

Feature

FeatureCelebrant of Life

April 1974 -

Feature

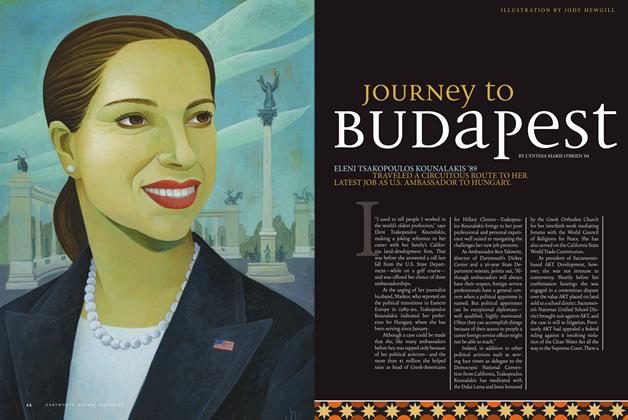

FeatureJourney to Budapest

Nov/Dec 2010 By CYNTHIA MARIE O'BRIEN ’04 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1958 By JAEGWON KIM '58 -

Feature

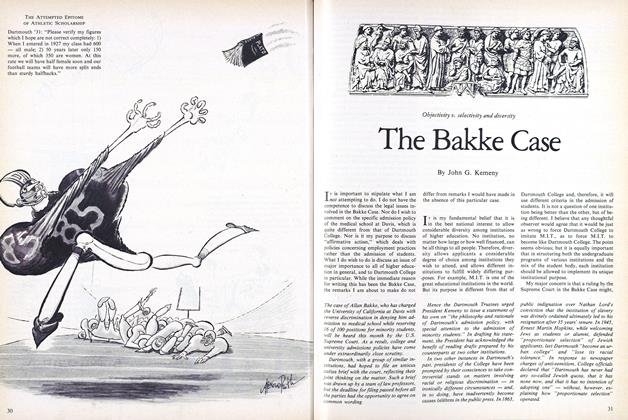

FeatureThe Bakke Case

OCT. 1977 By John G. Kemeny