By Samuel French Morse'36. Denver, Colo.: Alan Swallow, 1964.91 pp. $3.75.

Much of the pleasure of this volume comes from watching a fine craftsman at work. Mr. Morse clearly enjoys a technical challenge: he chooses the most restrictive verse forms; he experiments with all kinds of stanzas; he almost always uses rhyme. He can pick the last form one would think appropriate to a subject, and still make the poem work. He writes a long, lazy poem, ATrip Outside, in heroic couplets. He writes a poem in praise of simplicity, HancockPoint, in the most intricate of all lyrical forms, the villanelle.

Variety is the keynote of this volume, variety of form, of subject, of tone. Mr. Morse writes about dogs, butterflies, birds, crayfish, exotic animals from "aardvark" to "zebu" (A Game). He writes several fine poems about childhood, and balances them with chilling studies of adult hatred and guilt. He writes of the city, the seashore, the stars. He even writes a poem about a Dartmouth reunion, although it is not, I fear, one of his better poems. There is no dominant tone to this collection. One finds humour and sadness, fantasy and fact. There is more wit in these poems than one first realizes. Take, for instance, The Poem, which suggests by its title that it might be Morse's own comment on his work. He considers what happens when one picks up a handful of "dripping pebbles," and concludes: "Whatever runs between / Your fingers may be lost, but still you touch / The fragments of the world, for what they mean." What is the tone of this last phrase? Do "the fragments of the world" "mean" something, or don't they? Clearly, Morse hopes that the fragments of his world, his experiences, his poems, do mean something, but he makes no claim.

This balanced view of himself is one of Morse's real strengths. He realizes that his experiences, though varied, are not unusual. He is, we learn, a teacher in an urban university; he has a place at the shore, a family; he has read the right books. The pattern of his life is familiar, and so, generally, are the subjects of his poems. How can one make the "fragments" of a familiar world "mean" something without sounding trite or precious, without denying what one is? This is the essential problem for the poet anchored in domestic and academic life.

Morse solves it, I think, and he does so through his balance, his restraint, his refusal to force significance upon us. Here, the verse forms of A Trip Outside and Hancock Point begin to make sense. In the first poem, the poet records a family trip to a nearby island. It was a great adventure for them, but it was still just a safe, domestic outing. The meter, the heroic couplet, keeps the experience in perspective; it emphasizes, by its heroic connotations, the importance of the day, while underlining, through its incongruity, the difference between this and a "real" adventure.

The second poem, the villanelle in praise of simplicity, is a simple poem until, in the last stanza, the poet calls attention to the incongruity of form and subject: "A rhyme for rustics, like a villanelle." Here, the poet, aware of his sophistication, laughs at his own "folksiness." Yet he is also, justifiably, proud of himself, for he has written a villanelle which is, almost, "a rhyme for rustics." He has, in short, found the best of both worlds. So will the reader of TheChanges.

Instructor in English

ANY BOOK reviewed in the "Dartmouth Authors" section of the AlumniMagazine is available through the Dartmouth Book Store, Hanover, N. H.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Quest for Quality

July 1965 By STEWART LEE UDALL, LL.D. '65 -

Feature

FeatureSidney Chandler Hayward '26

July 1965 -

Feature

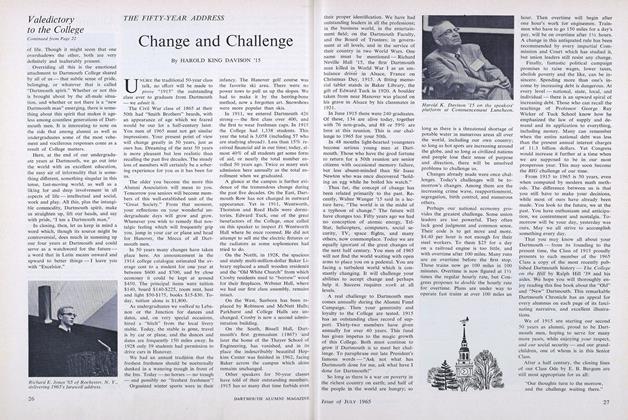

FeatureChange and Challenge

July 1965 By HAROLD KING DAVISON '15 -

Feature

FeatureTucker Heads Alumni Council

July 1965 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1965 -

Feature

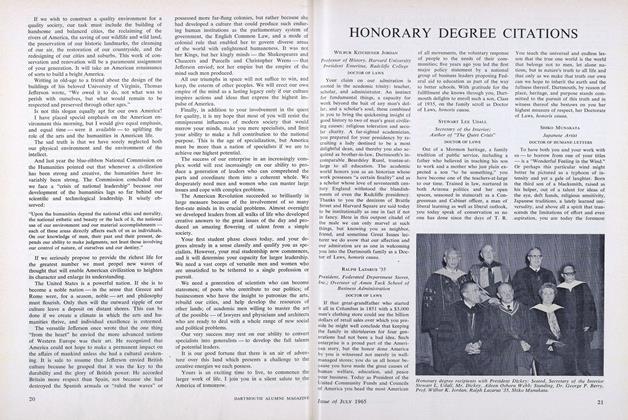

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1965

Books

-

Books

BooksThe latest musical composition

MARCH 1932 -

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

February 1933 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

MARCH 1966 -

Books

BooksTHE SOURCES OF "MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING,"

February 1951 By H. M. Dargan -

Books

BooksIN CLEAN HAY.

January 1954 By MAUDE D. FRENCH -

Books

BooksThe Evolution of the Vertebrates and Their Kin.

May 1912 By R.F.