THE COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR

EACH century there is, of course, only one Class of '65. By chance or by design, your year has been a pregnant one in American history.

The levy of a Stamp Tax, the promulgation of the Virginia Resolves, the cry "Taxation without representation is tyranny," and the making of a memorable speech by a man named Patrick Henry were some of the occurrences witnessed by the members of the Class of 1765.

A century later another Class of '65 had its commencement a few weeks after the conclusion of the Civil War as the nation still mourned the death of a martyr president. These students, in turn, saw the American people turn their full energies toward the consummation of the Industrial Revolution, the winning of the West, and the development and abuse of the natural resources of our continent.

Your year of '65 is both a time of troubles and a time of hope. It is a time that will involve an uncommon test of the mettle of your class and your generation.

One can make out a convincing case, I think, that the two most extraordinary, most revolutionary, chapters in the history of the American republic have been the first and the last.

From its beginnings in 1765 to the inauguration of President George Washington the American Revolution marked a creative climax in our national life. Its essential ideas — the right of revolution, the principle of federalism, the consent of the governed — have become polestars of democratic thought; and their originators Jefferson, Franklin, Adams, Madison — are eminent philosophers of Western democracy.

The second climax, I would suggest, has occurred during the past quarter century. It has involved a revolution in world politics and a revolution in technology, and it has transformed modern life and the pattern of world power.

In your lifetime the American people have participated in the most destructive of all wars, have unlocked the secrets of nuclear fission, have helped found the United Nations, and have seen with satisfaction the founding of nearly seventy new nations by a series of peaceable American revolutions that ended the era of colonial empire.

Rapid, revolutionary change and the cold war conflict have dominated our lives. A surge of science and a willingness to provide world leadership have enlarged our prowess and expanded our influence in the world at large. The pace of conflict and change will surely continue: today we confront new perils abroad, stand at the threshold of outer space, and must ready a new response to the rising expectations of the new nations.

In the foreseeable future, the struggle for a stable world will continue to command a major portion of our budgets and our energies. Any peace in our time will be, at best, uneasy and uncertain. We must persist, however, with faith that the "balance of terror" will prevail. Man's hope is that world statesmanship will mature in time, that no suicidal miscalculation will occur. In the long run peace will come only if our alliances hold, our individual commitments are widened, our leaders are wise, and our cause is right.

In the years ahead many of you — as members of the Peace Corps, as soldiers, as diplomats, as teachers, or as businessmen — will constitute the American presence around the globe. Events will take you to unheard-of places and you will be challenged to understand primitive lands and help strange peoples solve the age-old problems of emerging societies.

I salute, in advance, those who choose to forswear the comforts of modern life for the satisfactions of service, those who realize that we must share our knowledge and skills to make world peace and progress possible.

Your generation will be tempted at every hand by ease and affluence. Personal pleasure will compete with the public good. Selfish pursuits will compete with solutions to issues that trouble the world.

IN 1965 our military power is preeminent, our economy is in its longest sustained surge in history, most Americans enjoy unprecedented personal prosperity, and our technology races from triumph to triumph.

American society is, in one sense, a fantastic success. However, our performance is uneven and our preoccupation with power and "progress" casts doubt on our willingness to sustain those ideas and ideals that can magnify the American mind, and make our example meaningful.

Many years ago Thomas Henry Huxley asked this question of an American audience:

"I cannot say that I am in the slightest degree impressed by your bigness, or your material resources, as such. Size is not grandeur, and territory does not make a nation. The great issue, about which hangs a true sublimity, and the terror of overhanging fate, is what are you going to do with all these things? What is to be the end to which these are to be the means?"

His inquiry is especially apt, a half century later, in 1965, for we have grown too fast to grow right.

In the long run we will continue to command the world's respect only if we elevate and upgrade those things which add new quality to American life.

Life is good — but the good life still eludes us. Our standard of living is admittedly high, but measured by those things that truly distinguish a civilization, our living standards are hardly high at all.

We have, I fear, confused power with greatness. This error has caused many to question the quality of American life. At the time of the 1961 inauguration the poet Robert Frost dared America to aspire to a "new Augustan Age of poetry and power." President Kennedy gave eloquent and insistent emphasis to excellence. And President Johnson has underscored the importance of enlarging American culture by his effort to enlist the American people in the search for a Great Society.

I have chosen this morning to center attention on the quest for quality in American life, for we have reached the stage in our development where new achievements and goals are needed if the full promise of our society is to be fulfilled.

Three weeks ago nearly a thousand Americans participated with the President and Mrs. Johnson in a White House conference on the quality of the American environment. The verdict of the conference, tersely expressed, was that we are steadily diminishing the heritage of our cities and our countrysides.

It will take a sustained effort of several decades to rebuild our cities, save our countrysides, and rescue our rivers. We can transform the American scene and make it worthy of our wealth only if a new generation of designers and conservationists and concerned citizens turn back the tide of blight and disorder that dominates our land.

By our failure to conserve what should be conserved for our children and the future, by our failure to build attractive cities, by our failure to control the contamination of essential resources, we have forfeited our claim as conservationists of conscience.

Many have indicated these failures of our stewardship. In a recent sermon Edward Durrell Stone, the eminent architect, asserted that in the short space of fifty years Americans have converted their country from "one of the most beautiful to one of the ugliest."

A few days ago the Saturday Review summarized the spoliation of America in these words:

"Our environment is being subjected to a vast debasement from which literally no one can escape. Water is increasingly unfit not only for drinking but also for bathing, boating, and fishing. Hills that were once green are today scarred and pitted. Farmland and field and forest, sources of food and resources for recreation, are ravaged. And the air we breathe is choked with health-destroying filth."

The overpowering paradox in all this is that the quality of the American environment has declined with each new economic advance. Pollution and blight have emerged not from poverty, but from prosperity. We have been so busy concentrating on personal ease and private convenience that we have failed in our stewardship of those resources all men must share.

We lead the world in wealth and power. But we also lead in pollution and blight and despoilment: we have the most cars - and the worst junkyards; we are the most mobile people on earth - and have the most congestion; we produce the most energy, and have the most polluted air; our factories pour out more products and our rivers carry the heaviest pollution; we have the most goods to sell, and the most unsightly signs to advertise their worth.

IT will take a vast effort to improve the American environment. However, the challenge has been thrown down to the American people, and forces of rescue and renewal are already in the field.

The cost of the "new conservation" will be high. It will take years of coordinated effort by public men, men of science, leaders of business, and organized conservationists to win the war against ugliness and decay. Above all, we will need new concepts of social responsibility. As parents and teachers we must instill in our children a love of the earth and an abhorrence of filth and clutter. Properly conceived, conservation is a moral issue and should be presented as such. The earth is our home - and cleanliness is, indeed, next to Godliness.

The stake in this straggle is, simply put, a life-giving environment. Order, beauty, good design, fresh air, clean water involve not only a vital American tradition but the promise of life itself.

If we wish to construct a quality environment for a quality society, our task must include the building of handsome and balanced cities, the reclaiming of the rivers of America, the saving of our wildlife and wild land, the preservation of our historic landmarks, the cleansing of our air, the restoration of our countryside, and the redesigning of our cities and suburbs. This work of conservation and renovation will be a paramount assignment of your generation. It will take an American renaissance of sorts to build a bright America.

Writing in old-age to a friend about the design of the buildings of his beloved University of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson wrote, "We owed it to do, not what was to perish with ourselves, but what would remain to be respected and preserved through other ages."

Is not this slogan equally apt for our own America?

I have placed special emphasis on the American environment this morning, but I would give equal emphasis, and equal time — were it available — to uplifting the role of the arts and the humanities in American life.

The sad truth is that we have sorely neglected both our physical environment and the environment of the intellect.

And last year the blue-ribbon National Commission on the Humanities pointed out that whenever a civilization has been strong and creative, the humanities have invariably been strong. The Commission concluded that we face a "crisis of national leadership" because our development of the humanities lags so far behind our scientific and technological leadership. It wisely observed:

"Upon the humanities depend the national ethic and morality, the national esthetic and beauty or the lack of it, the national use of our environment and our material accomplishments each of these areas directly affects each of us as individuals. On our knowledge of men, their past and their present, depends our ability to make judgments, not least those involving our control of nature, of ourselves and our destiny."

If we seriously propose to provide the richest life for the greatest number we must propel new waves of thought that will enable American civilization to heighten its character and enlarge its understanding.

The United States is a powerful nation. If she is to become a noble nation —in the sense that Greece and Rome were, for a season, noble - art and philosophy must flourish. Only then will the outward ripple of our culture leave a deposit on distant shores. This can be done if we create a climate in which the arts and humanities thrive, and individual excellence is esteemed.

The versatile Jefferson once wrote that the one thing "from the heart" he envied the more advanced nations of Western Europe was their art. He recognized that America could not hope to make a permanent impact on the affairs of mankind unless she had a cultural awakening. It is safe to assume that Jefferson envied British culture because he grasped that it was the key to the durability and the glory of British power. He accorded Britain more respect than Spain, not because she had destroyed the Spanish armada or "ruled the waves" or possessed more far-flung colonies, but rather because she had developed a culture that could produce such enduring human institutions as the parliamentary system of government, the English Common Law, and a mode of colonial rule that enabled her to govern diverse areas of the world with enlightened humaneness. It was not her Kings, but her kingly minds — the Shakespeares and Chaucers and Purcells and Christopher Wrens — that Jefferson envied; not her empire but the empire of the mind such men produced.

All our triumphs in space will not suffice to win, and keep, the esteem of other peoples. We will erect our own empire of the mind as a lasting legacy only if our culture inspires actions and ideas that express the highest im- pulse of America.

Finally, in addition to your involvement in the quest for quality, it is my hope that most of you will resist the omnipresent influences of modern society that would narrow your minds, make you mere specialists, and limit your ability to make a full contribution to the national purpose. This is the age of specialization, but America must be more than a nation of specialists if we are to achieve our highest potential.

The success of our enterprise in an increasingly complex world will rest increasingly on our ability to produce a generation of leaders who can comprehend the parts and coordinate them into a coherent whole. We desperately need men and women who can master large issues and cope with complex problems.

The American Revolution succeeded so brilliantly in large measure because of the involvement of so many first-rate minds in its crucial problems. Almost overnight we developed leaders from all walks of life who developed creative answers to the great issues of the day and produced an amazing flowering of talent from a simple society.

Your first student phase closes today, and your degrees already in a sense classify and qualify you as specialists. However, your real studentship now commences, and it will determine your capacity for larger leadership. We need a vast corps of versatile men and women who are unsatisfied to be tethered to a single profession or pursuit.

We need a generation of scientists who can become statesmen; of poets who contribute to our politics; of businessmen who have the insight to patronize the arts, rebuild our cities, and help develop the resources of other lands; of academic men willing to master the art of the possible — of lawyers and physicians and architects who are ready to deal with a whole range of new social and political problems.

Our very success may rest on our ability to convert specialists into generalists — to develop the full talents of potential leaders.

It is our good fortune that there is an air of adventure over this land which presents a challenge to the creative energies we each possess.

Yours is an exciting time to live, to commence the larger work of life. I join you in a silent salute to the America of tomorrow.

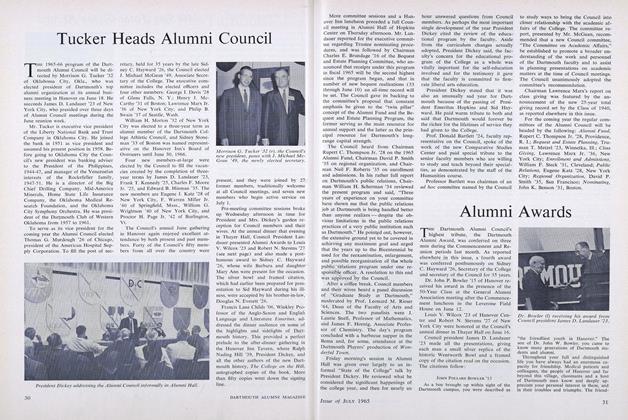

Secretary Udall with Trustee Thomas B. Curtis '32.

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover Story1894 FACULTY REPORT ON COEDUCATION

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Balance

MAY 1997 By James Wright -

Feature

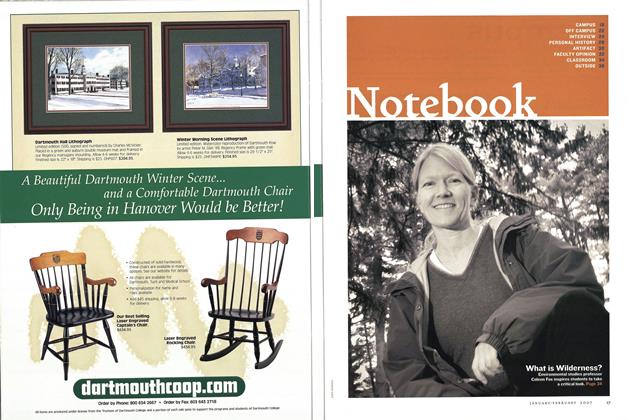

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureFeast and Famine

MAY 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Sept/Oct 2007 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

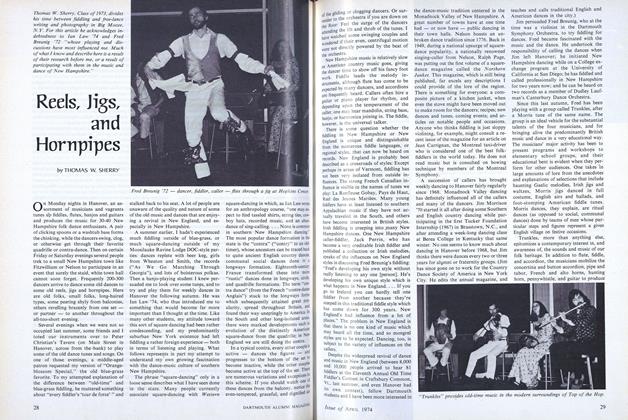

FeatureReels, Jigs, and Hornpipes

April 1974 By THOMAS W. SHERRY