When we were at Dartmouth in the early'7os the College still seemed a mite uneasy about the secular/nonsecular divide; it stood somewhere between the devil and the deep blue sea. The place was no longer institutionally biased against certain religious groups—-Jews, Catholics—as it once had been. But neither had it forgotten traditional links with its Protestant missionary-school past, nor had it seen the teaching of religion complete its evolution to the vigorously secular, proudly critical, searingly intellectual pursuit that it is today. An illustrative anecdote: I was taking a course on the Synoptic Gospels taught by David Adams, one of the bright young professors who were helping the religion department build its modern reputation as a fascinating neighborhood that every student should visit. Adams was a secularist, as were most of the religion professors, including all the newer ones. In Adams's classroom everything was above-board—clean and critical, not to say clinical. When Adams invited us over to his house for coffee and discussion in a less formal setting, however, some of us began to open up about how our booklearning was arm-wresding our religious faith. The great majority of us were Christians of one stripe or another, and the question of whether the Gospels were or were not journalistic got right to the core of our being. Adams did not, I remember, discourage these lines of inquiry. If he tried to set us straight regarding the historicity of Gospel parables, he did so gently. Adams was a good bridgebuilder in that transitional time.

Meantime, elsewhere on campus, I was taking English and comp lit courses—Harry Bond's "Bible Literature," Peter Bien's "Joyce and Kazantzakis"—that seemed to encourage considerations of spirituality much more overtly than did the offerings in religion. Jeff Hart kept his devout Catholicism out of the classroom pretty effectively, but then along came his Dartmouth Review which had apparently been talking to God, a la Moses, and had learned that He wasn't happy with the College's drift toward secularism.

As I say, it was a confusing time. But it was, I thought, a healthy time. The College, founded with Jesus and God in mind, was doing some soul-searching as to what role those two—and Moses and Abraham and Mohammed and the Buddha and a heavenly host of others—would, could, or should play on a contemporary campus. If any.

Since that era, a lot has happened in society generally and at Dartmouth specifically vis-a-vis religion. The rise of the religious right has put the relationship of church and state back on the table as a national issue, while movements as different as Buddhism and Pentacostalism have seen spectacular growth in the U.S. A $5 million Jainist temple has risen in the suburbs of Detroit. William Bennett has become an evangelist for what are traditionally called Christian values, even as institutions of higher learning have, in booming economic times, become more firmly dedicated to training students in a "practical" manner, a manner that will insure a good job and that will keep parents, who have opened the vault to meet tuition payments, happy. God is all well and good, but can He help you land that internship on Wall Street?

At Dartmouth we have, just recently, built a new jewish center. We have added courses in Holocaust studies. We have taken an uneasy look at our exclusionary past. We have grown increasingly multicultural. We have seen William F. Buckley Jr. come to campus to deliver a talk on "God and Man at Dartmouth." And we are, in the midst of all this, searching for a new college chaplain (see sidebar, page 42).

This is, clearly, a good and proper time to be looking at religion as it exists on the Hanover plain. Is the transitional period over? Is the College still a god-fearing place? (Should it be? Should it not be?)

first, the genesis.

"Dartmouth was founded by a man who was basically an evangelical preacher," says Jere Daniell '55, professor of history and a specialist in Colonial America. "He gave hundreds of sermons, trucking around the country in eastern Connecticut and Rhode Island. The reason we exist as Dartmouth is that he wanted to create a New Light Movement, as it was called in Colonial Connecticut, and he was seen as a pariah by some of the orthodox Protestant establishment down there. So he was looking around for a place to start his Indian school, and he found this weird place up in New Hampshire. He thought he could train the Indians and other folk up there. So as far as religion is concerned, regarding the founding of the College—it was right at the core."

A note in passing: Religion was at the core of all colleges that were a founding back then. Says Scott Brown '78, dean of Dartmouth's Tucker Foundation: "The bastions of higher education today—the Ivy League, many state schools—were started by Christian denominations to educate religious leaders."

The question of whether Dartmouth should remain theologically based came to the fore very quickly. As soon as Eleazar was out of the president's chair, secularization began an early creep across campus. "Religion was so far in decline that only one member of the class of 1779 was known publicly to have been a professing Christian," wrote R.N. Hill in The College on the Hill. Interestingly, the religious faction regained some purchase when, in order to preserve the College's independence, our heritage as a missionary school became a key argument in the Dartmouth College Case, which Daniell distills into "the old Congregational curmudgeons winning over the modernists."

Regardless of the impious class of '79, Dartmouth's Trustees continued to appoint presidents with ministerial backgrounds. Dartmouth's professed institutional saintliness was not always supported by deed, and recent revelations of Jewish quotas in the admissions department in no way represent the first instance of God-fearing Dartmouth doing the wrong thing. "We had a pro-slavery president during the Civil War," Daniell points out. "Nathan Lord was this fervent guy whose justification for slavery was purely Biblical. All these old ministers—Connecticut friends of Eleazar Wheelock, then guys like Lord—ran the College right through the 1800s, and were terrible for the place. Dartmouth became a declining institution. And then came Tucker."

William jewett Tucker was named president in 1893. He had the perfect blend of resume and inclination to shift the College's direction (see sidebar, page 39). Tucker was a minister but a modernist. The Trustees felt that the first credential justified their choice, while the second might serve to shake up a hidebound school.

Tucker wanted students to study, meanwhile saving some "room in their hearts" for Christianity: a sort of extracurricular pursuit. He appeared massively progressive when he said to his Protestant students, faculty, and administrators, "Here is a place where all who have religious aspirations of any form may unite in any religious service." Says Daniell: "Tucker was a theologian with an entrepreneurial spirit. He handed off to Hopkins, who launched the institution into its non-religious period."

Well, sort of. Ernest Martin Hopkins '01, with his business background, completed the transition that sent Dartmouth down its present path; Tucker-to-Hopkins was a nifty end-around to the twentieth century. But Hopkins continually clouded the religion issue. He said in his 1919 valedictory that "the spirit of Christianity" involved "working not only for self-interest but for the common good." In 1931 he asked students not to "totally give up on God." Meanwhile, he oversaw the end of compulsory daily worship at Dartmouth, a change as fraught as Tucker's call for religious tolerance. In the fall of 1925 attendance at all services, including Sunday vespers, became strictly voluntary. But, then, yes: Hopkins oversaw an admissions of fice with quotas. Letters exchanged between an alumnus and the College director of admissions in 1934, when Hopkins was president, became Exhibit A in last year's brief brouhaha over past anti-Semitism, detailing as they did the College's systematic exclusion of Jews.

Taken in all, Hopkins's tenure stands as progress toward secularization. But it is not at all clear that Hopkins would want any credit. In his now famous 1945 article published in the New York Post—the article that became a flash point item in the Buckley-v-Dartmouth debate last year—Hop kins stood as a vigorous preserver, protector, and defender of the College's waspish charter: "Dartmouth is a Christian College founded for the Christianizing of its students." The irony is, of course, that by 1945 Eleazar Wheelock's mission was history, and, in fact, the essay writer had been personally instrumental in leading the College away from its founding principles.

Yet Dickey saw Rollins Chapel standing forlorn, often empty. He sensed throughout the campus a troubling diminution 0f... Of what? Ethical standards? Institutional character?

In 1951 he established the Tucker Foundation, named in memory of the man who had so elegandy blended morality and modernism. Its charge: To farther the moral and spiritual life of the College.

What happened next was fascinating. The '60s happened, and all of a sudden "moral and spiritual" uplift seemed a clarion call to social activism. The Tucker Foundation, which Dickey might have seen as a way to get the minister from the White Church talking to the pastor up at the new Aquinas House, suddenly became a hotbed of outreach activity, and also a space where you could organize an anti-war demonstration. What God had to do with all this was in the eye of the beholder. Meanwhile, over at the religion department, the secularists were carrying the day.

In the shadows, conservatives and traditionalists clung to their image of a bygone Dartmouth—hoping that holy College might rise again.

When I was admitted in December of 1970 from a public school system in eastern Mass achusetts, our local pastor was appalled. "You're not going, surely," the old white-haired man said. "They hate Catholics there." He couldn't figure why any kid would choose Dartmouth over the warmly welcoming Jesuit schools such as B.C. and Holy Cross.

Images fall hard. As late as 1970, priests still figured Dartmouth hated Catholics. Certainly rabbis felt Dartmouth hated Jews. Obviously no one could conclude that Dartmouth was courting Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, or smart kids from other then-exotic religions. There was still work to be done.

It should be said before proceeding: There was work to be done off-campus, in the public's perception. On campus, everything was fine, and had been for a while. In Hanover I never once felt excluded due to my Catholicism. Much more significantly, Bob Schreibman '57 says the same about his Jewishness.

Schreibman—make that Rabbi Schreibman of Temple Jeremiah in Northfield, Illinois—matriculated from New Jersey at a time when Dartmouth's institutional discriminations against Jews were still in place. Yet he says, "I did not find any anti-Semitism at Dartmouth. None. Well, maybe one kid was anti-Semitic—but he was crazy." Schreibman remembers a schizophrenic Dartmouth, a place with mechanisms that seemed biased but with no bias in its heart. "I was looking through my '57 newsletter just the other day, and maybe for the first time in my life I realized how waspy Dartmouth was," he says. "It never felt that way to me. Certainly it was a strange place for aJew. For instance, to participate in Jewish life you had to be a member of the Dartmouth Christian Union—the Jewish Life Council was part of the DCU. That struck me as strange, but I was sanguine. I enjoyed doing Christian Union activities—playing chess at the V.A. hospital, chopping wood. Our feeling back then was: Don't make waves. Be the best that you can be within the systems as they are.

"Certainly Dartmouth had quotas, and it was not a Jewish campus—it was not Harvard, it wasn't Brandeis, it wasn't Columbia. But Jews were fine at Dartmouth. I joined one of the two Jewish fraternities and had great fun. I loved Dartmouth." Rabbi Schreibman's son and daughter went to Dartmouth in the 'Bos, and "they loved it too. Things had changed, of course. There were no Jewish fraternities anymore, everything was integrated. My son joined a frat, my daughter joined a sorority, and there were some Jews in each, some non-Jews. My kids found that there was no anti-Semitism in that era, despite the presence of the Dartmouth Review and that crowd."

The evaporation of institutionalized religious discrimination in the 1960s and 70s, followed by President James Freedman's courtship of a multicultural student body, saw Dartmouth drift ever farther from its missionary origins. Then, in the 1980s, another dynamic was brought to bear on the secular/nonsecular divide: Money, big-time money. The salaries offered to graduates from places like Dartmouth were suddenly immense, the competition for those salaries was immense, and the tuition asked of parents was immense. The job of places like Dartmouth was to prepare kids for a world in which accomplishment was measured in money. If a parent heard that classroom time was being squandered in furtherance of spiritual growth when he or she was shelling out 30 Gs in pursuit of a successful material life—well, a letter would be written.

Off in the corner, the Tucker Foundation continued to tell the spirit-seeking urchins who arrived at its door to keep the faith. Some sociologists see 1990s America as a backlash to the 1980s, and when looking at religion this is a useful perspective. Surely there was going to be a pendulum swing back from our blind quest for mammon toward something more spiritual. In a democracy, where people can think and feel as they will, that much was predictable: People would find themselves unsatisfied by money alone, and would look for something deeper, or at least something else.

What about at Dartmouth? I asked that question of people at Dartmouth.

"There has, no question, been a growing interest among young people up here regarding religious life and spiritual issues," says the Tucker Foundation's Scott Brown. "Tucker is very busy right now, in a variety of ways." There are today over a thousand students involved in Tucker-organized community service projects, and more than 700 involved with Tucker-sponsored student religious organizations. The Foundation sponsors monthly campus ministers meetings, which only a short time ago would have meant an Episcopalian and a Presbyterian having coffee at Lou's. "These days Hillel, Al Nur, and the Aquinas House folks get together for bagel breakfasts," says Brown. "Bagels are good with hummus. The students absolutely relish the interaction,and learning about the other guy's faith." Today's student body includes practitioners of several forms of Protestantism, Catholicism, Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, the Quaker faith, Christian Science, the Baha'i faith, Native American religions and Mormonism.' We currently have 19 recognized student religious groups at Dartmouth, says Brown, and certainly his Foundation cannot pretend to educate in all denominations. Instead, Tucker seeks to be an incubator of moral behavior and spiritual advancement. "At first, the conceit was for Tucker to somehow fill a spiritual void. Then in the '6os the place listed toward social issues. Now it s a blend. I see its job as fourfold: To raise major issues of social and ethical concern on campus. To provide opportunities for students to explore their own interests in social issues through local volunteer work in the Upper Valley or off-campus fellowships. To create a home on campus for exploration and expression of religious faith with local churches and student groups. And then, fourth, to be a kind of symbol of the College's commitment to the non-curricular side of education, the spirit and conscience side of education. Colleges across the country have become so secular, places like Tucker have a duty to ask, 'ls there any role beyond intellectual development that the College is required or should—perform?'"

At Dartmouth there has also been a tremendous, corresponding surge in business at the religion department. These days when Professors Hans Penner and Ron Green open the doors for their "Patterns of Religion" course, which examines cosmology, creation myths,Moses,Jesus, Krishna, Buddha, and lots of other fan matters, some 170 undergrads flood in. There are more than 60 religion majors, and nearly 500 students venture through the department in a given term.Penner, who is finishing his final semester at the College, remembers, "When I joined in 1965 the department had five professors. Now there are 13. We have an Islamicist, an Africanist, a specialist in Native-American faiths, Judaism. It's come a long way.

A "critical" view of religion means religion straight, religion neat—no seltzer, no ice, no olives, no twists. "We show them how to go about studying religion," says Penner. "Our department really isn't concerned about religion on campus. We show them how religion works in the world. It's a topic like no other. You can't do much in philosophy or in government if you don't understand religion. Certainly this helps students understand how religion works in their own lives, but that's not our job. We talk about the myth of Jesus as we talk about the myth of Buddha, and that shocks them once in a while."

Don't misunderstand, Penner is not a hard guy. "Teaching is a very risky thing," he says. "You never know how a student will absorb this stuff. You can really screw this up. I realize some students come to the department for 'religion.' But when they do, and they're asked to be very critical, many of them find this very stimulating. I sense at the end of class there's an awful lot of talking going on, talking that continues outside."

Scott Brown hears some of the talk: "While the majority of students at Dartmouth are content with religious studies here—the way they're presented—there are some who say they don't feel they can express their views on religion in the classroom, or that issues having to do with religion don't come up. Academia in general is a fairly isolating place for someone with strong religious views."

Penner doesn't disagree, but again asserts his responsibility: "We're coming at it from an opposite way, and it's the only way to teach this topic. It's not just Jesus. The other day a student wanted me to announce a Free Tibet meeting, and I said I'm not going to do it. You're asking me to free Tibet. Maybe I don't want to. But more to the point, we are very, very careful about announcements made in our classrooms. We are teaching a subject here, not preaching."

Since this is the case, Brown treads lightly when promoting Tucker/faculty interactions at Dartmouth. He sends a letter to all teachers each year saying that his Foundation stands ready to help if educational aims can be abetted by a little outreach. "Learning is often better and deeper when there's a hands-on experience," he says. Penner feels Brown's mild overtures are absolutely appropriate, though he seldom takes the dean up on his offer. The fact is, what few faculty clients the Tucker Foundation has come from places like psych, not the department we used to call "God."

Brown and Penner, I'm surprised to learn, agree on much: The separation and comfortable coexistence of church and state; the acknowledgment that, for all the rhetoric, young minds do not necessarily compartmentalize fact and philosophy so neatly; the realization that this is a tricky business, best handled carefully. Furthermore, they agree that the religious profile of the campus is dynamic rightnow, and that this has a lot to do with the immediate past president. "The College is still very American, and by that I mean very Protestant Christian, in its ethos," says Penner."But Freedman made a dent. His concern with a diverse student body has meant a lot more Koreans, a lot more Japanese. I can certainly see it in my classroom, by golly—the texture of the student body is shifting, and this has made a big difference culturally and then, of course, in terms of religion. I have a lot of Indians in my 'lndian Religions' classroom, and that's really neat. The dorm life must be changing greatly, with kids interacting with other cultures. I see no tension among the students about this, but you've got to understand: The students these days are bright, and accept that this is the way it should be. They think coeducation goes back to Eleazar Wheelock."

Brown concurs: "The Freedman tenure helped. For a long time, it wasn't only Jews who felt, 'You shouldn't go to Dartmouth, they don't like us there.' Now, it's known that Dartmouth will welcome people of any faith. Under Freedman, the College seemed more concerned about ethical, moral behavior."

What Freedman did: As a Jew, he took on the Dartmouth Review in a public, very personal way when the paper ill-advisedly baited him with the Hitler stuff. The Review has really never recovered from that body blow. Then, last year, again as a Jew, he . made public the College's long-gone discrimination. As the institution's chief recruiter, he sought to lure minority cultures. As the institution's philosophical head, he spoke often about "idealism" and role-model behavior on the part of administrators, faculty, and students. He boosted what some would call ethical behavior, others might term civility, and still others might label religious ideals. He used his bully pulpit to urge Dartmouth's citizens to be kinder and gentler.

But he never said Dartmouth was any kind of religious place. To the contrary, he supported edicts that shouted to all: Come to Dartmouth, the Secular College on the Hill. The incident that gained the most note seemed silly to many (including, it should be said, the author of this article). A week before Thanksgiving break in 1996, Olivia Chapman, assistant director of public programs, sent a message to Glee Club director Louis Burkot: "The Of fice of Public Programs does not want the bulk of the offering [at the traditional tree-lighting ceremony on the green] to be traditional 'Christian' Christmas Carols."

Well, "Frosty the Snowman" will only get you so far, and Louis Burkot canceled the gig entirely, explaining "there is not time to obtain and learn a whole new set of pieces." The ban seemed wholly ill-advised, it wore its Grinchy-ness on the sleeve. The carol sing was one of the warmest, least in-your-face activities Dartmouth sponsored each year; I remember attending with classmates Joe Yastrow and Victor Zonana, both Jews, and they sang along. Moreover, in a College that professed to be newly proud of allowing all religions to celebrate, why stop one from doing so? Penner does point out, not vis-a-vis the carol sing, that Dartmouth "doesn't have to do anything extra to be empathetic toward Christians, it's in the bones of this place." But was the carol sing extra, or merely pleasant?

A footnote to the conflict: This past December there was another dustup on campus when the College tem to distribute C.S. Lewis's Mere Christianity to all students via the Hinman mail. At the time Brown said of the mailing, which some in the administration considered a solicitation: "We can anticipate that a large number of students will take offense to this." He might have anticipated, too, charges of censorship, which came fast and furious. The College quickly yielded. It seems clear that Parkhurst will be forced to weigh Constitutional protections against politically correct sensibilities in any number of religious issues to come.

Anyway, after carols went unsung in 1996 and Jewish quotas were revealed in 1998, William F. Buckley Jr. responded with his "God and Man at Dartmouth" essayin The New York Times and a visit to campus a year ago during which he spoke on the topic at, of course, Rollins Chapel. The speech was a fine and eloquent one. The linchpin of both his essay and his talk was the famous 1945 quote from Hopkins regarding the College's duty to Christianize students. Buckley's opinion was that Hopkins's opinion was sound, and perhaps should obtain in the new millennium.

Now, then: Does William F. Buckley like to be provocative?

Is the Pope Catholic?

But a funny thing happened on the day after Buckley's speech. Nothing. Zippo happened. The newjewish Roth Center threw open its doors. Freedman retired. The Tucker Foundation went back to its good works. Hans Penner and company went back to theirs.

Why did it all just wash away?

Because there's no real debate at Dartmouth right now. Dartmouth is institutionally dedicated to being perceived as a secular place. It feels this is the way to survive and thrive. It will suffer the small religious squabbles, but on the larger issue—Does the College have any basis in theology?—the answer is clearly no. We're going to educate,period, and if you want to get into big fights about whetherChristian principles are an interesting ingredient in elite education, well, you can hash that out with Notre Dame.

Thi appraisal of religion at Dartmouth—and this ar-tide—could and perhaps should end here. But there remains a nagging question ofvalues, which seem so intrinsically tied to the thorny question of religion. An institution that steers clear of religion by necessity steers clear of religious values—and aren't everyday values (work hard, play fair, don't cheat or steal) religious values at heart? As the College pledges firm allegiance to secularism, does it diminish itself in any subtle way?

No! shouts the national Campus Freethought Alliance. Dedicated to fighting the Campus Crusade for Christ and any other evangelical efforts, this group, headed by Dr. Paul Kurtz of the State University ofNew York at Buffalo, longs for the good old days of the 197 Os and '80s, when the new spiritualism was yet unborn. "There is now a concerted effort underway to repeal the secular society," says Kurtz. "The battle between faith and free inquiry was won two generations ago, or so we thought. Unfortunately, there are now shrill voices demanding their desecularization."

Well, we'll try not to be shrill as we ask again: What does secular Dartmouth stand for? "Not enough," says Scott Brown. "A good question," says Hans Penner, surprising us.

"Far, far too little," says our old, personal friend Peter Bien, professor emeritus, dedicated Quaker, part of the search committee that hired Brown, concerned onlooker.

I called on Professor Bien because I remembered, as clearly as I remembered the tensions spurred by Adams's Synoptic Gospels, the questions of spirituality raised and discussed in Bien's comparative literature courses. I remembered that the teacher clearly cared about messages in the texts. I learned subsequently that he cared about these questions as they applied to the world at large. "I can't tell you much about the student body today, as I haven't actually taught a course in three years," says Bien. "But I can tell you that it's very clear Dartmouth is a totally secular institution. It does pretend sometimes to have some kind of value system, but I don't think there's much of a value system at Dartmouth that differs from that of the United States at large. The message of Dartmouth is 'Be good, be smart, do well, make money, help society if you can, if it's not too uncomfortable for you.' I'm not saying Dartmouth is doing the wrong thing entirely. The religion department is one of the best, but the whole point of the religion department is that they're not religious they must not be. I can see it from their point of view, but I would say to you: It's both right, and it's wrong. It's not right, and it's not wrong. It's both. Maybe there should be two departments: religion, and values. Teach values. At Dartmouth today, we do not teach values."

If that is so, then what is the College's Ethics Institute for?

The Institute, established in the early '80s by faculty members including Penner's colleague Ron Green, is a curiosity and a complexity. It seeks to help teachers deal with ethical questions within their disciplines, and by encouraging anyone on campus to think about ethics, something surely trickles down—or so hope the Institute's leaders. The Ethics Institute does have a place in the classroom; it also has a place in the ether. It is hard to get a handle on, and somewhat outside this debate, as Green explains (see sidebar, below).

Certainly Bien doesn't feel the Ethics Institute or any other campus organization this side of Tucker is doing much to build moral men and women. "The Foundation is crucial," he says. "These students come to Dartmouth expecting to receive, but what do we offer? What Dartmouth does not do well is have students serve. What we're really out for is to have students get a resume and get hired by Chase Manhattan Bank. That's not service. So Tucker is important, butTucker is marginalized. Dartmouth's central ethos, which Tucker does not impact, is materialistic, self-indulgent, and goal-oriented. And what I'm saying is: Maybe that's not what the whole of life is about."

Scott Brown agrees. "Colleges across the country have become so secular, we need to ask the question: Is there any role they must or should play beyond intellectual development? Are we educating the whole person if we do not teach values? Should we be developing members of society that we all want to live with, and people who will make us better as a society?

"My view is, we should not be educating in a vacuum but for a purpose. Jim Wright reflected some of those thoughts in his inaugural speech—that the College should have an influence on the community, the community here and the community out there. Now, there are people very skeptical of such views. They say, taken to the extreme, such a mission would require faculty to engage in a kind of teaching and moral instruction we're not inclined to do. This will not come easily, but I have hope."

Hans Penner, approached for rebuttal, does not rebut. "I will not teach someone how to 'live within a religion.' That's ridiculous, it's not our job. But we ought to educate the whole person, and we are not doing it. I'm a strong advocate of what I call 'holistic theory,' and I wish we would use it to deal with liberal arts in the new century. Nobody's doing this, and with competition between colleges so fierce, it's dangerous to do it. We should be asking: What is education? What is educating the whole person? Ethics could certainly come into it, and I repeat: The study of religion is important in a liberal arts college because religion is so important in all cultures. If students remember how to go about analyzing religions critically, they learn a great deal about ethics, and different people's views of ethics, and the importance people attach to ethics. Let's decide what people mean when they say, 'We should teach values.'

"I'd like to see Dartmouth get a jump on this. It's going to be tough. Diversity, which is good, almost stops you from asking the questions of 'wholeness' and 'coherence.' When you put the stress on diversity and religion, you can't talk easily about the whole—the whole that includes an ethical component. But I'd like to have us look at it, and I've told Jim Wright that. He seemed amenable. A lot of times, just doing it—the critical exercise itself—pays off. You're not the same when you come out of it. You're better for it, whether you act on it or not."

Bien, Brown, and Penner all agree that Freedman changed the cultural and therefore the religious complexion of the College. They agree further that his challenge to the school had little to do with values beyond fairness. What is being asked, now, is for more esoteric soul searching. Such introspection, in an institution or an individual, is always hard and often dangerous.

It's interesting: The easy way is for Dartmouth to proudly and loudly proclaim itself a paragon of modern American education, doors open to all—a secular Par adiso, a secular Eden. The more difficult way is to ask itself: What do we forfeit when we forfeit religion? Don't call it Christian values, for goodness sake. Call it ethics, morals, a sense of what is right. Call it by another name. Call it soul.

Can the College lose its soul? Has it lost its soul already?

Contributing editor ROBERT SULLIVAN is editor of two recentbooks on religion in America, Blessed are Thou Among Women Do You Say That I Am? His latest book,co-authored with Michael Padden '75, if May the Road Rise to Meet You: Everything You Need to Know About Irish American History.

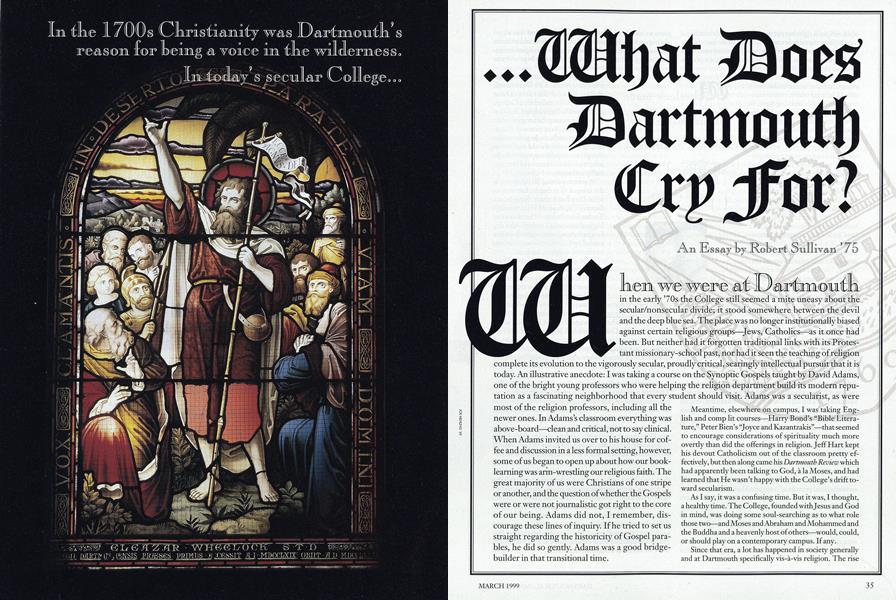

In the 1700s Christianity was Dartmouth's reason for being a voice in the wilderness In today's secular College...

Wheelock made It his business to awaken heathen of all cultural stripes and colors.

Tucker wantedstudents to save"room in theirWarts" for religionsa sort of extrascurricularpursuit.

Bod is all well and good, tut can He help you land, that Internship on "Wall Street?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

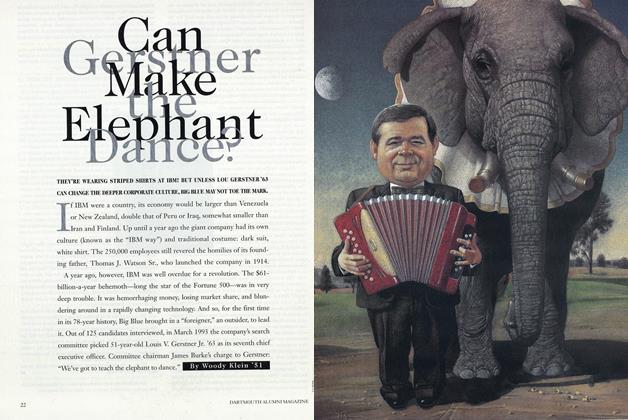

FeatureMoney and Luck

March 1999 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureFirst person

March 1999 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Article

ArticleA Tale of Two Libraries

March 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleExercising the Mind

March 1999 By Rich Barlow '81 -

Sports

SportsSilver Honors for Ivy Women

March 1999 By Sarah Hood '98 -

Article

ArticleStanding Together

March 1999 By James Wright

Robert Sullivan '75

-

Sports

SportsAt the Winter Games

April 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

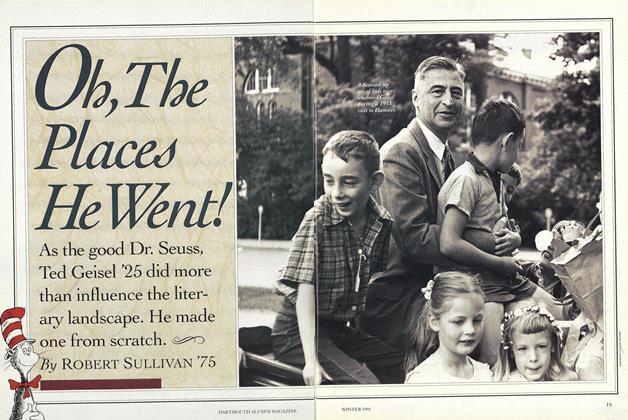

Cover Story

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticlePosthu-Mously, Norman Maclean Takes On a New Element

February 1993 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

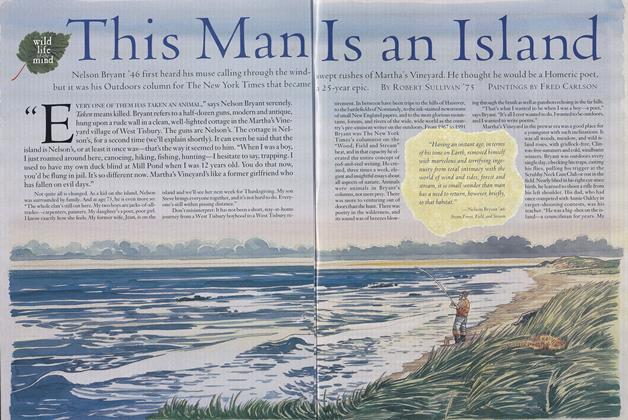

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

OCTOBER 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Off-Broadway

SEPTEMBER 1997 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

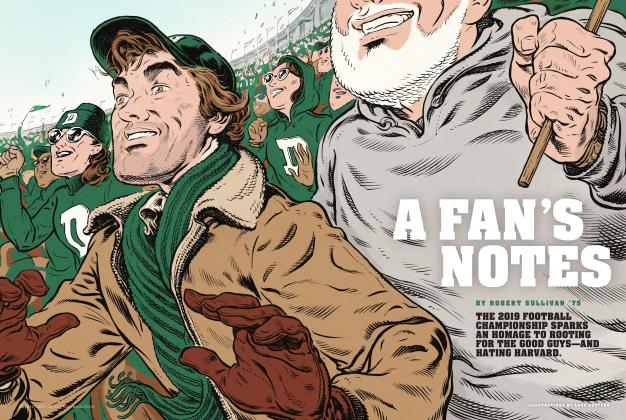

FEATURE

FEATUREA Fan’s Notes

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75