By RichardE. Welch Jr. '45. Middletown, Conn.:Wesley an University Press, 1965. 276 pp.$7.50.

Theodore Sedgwick has been treated roughly by historians. Like other New England Federalists who supported both the Alien and Sedition Acts and the abortive at tempt to deprive Jefferson of his presidential victory in the election of 1800, he has been criticized for his political ambition, his self-righteous manner, and his outspoken antagonism to political democracy. Richard Welch, the first historian to write a book length biography of the Massachusetts legislator, admits that Sedgwick exhibited these traits. Yet, unlike those who have argued that men like Sedgwick were a positive threat to the political principles of the new nation, Welch treats his protagonist with a good deal of sympathy. Indeed, Welch argues convincingly that despite an often unpleasant personality and an outmoded political philosophy, Sedgwick contributed "very real services" to both "state and nation."

Welch develops his argument in several ways. He traces Sedgwick's role in Massa-chusetts politics as a member of the General Court, as an influential Berkshire County lawyer who helped put down Shays' Rebellion, and finally as justice of the state Supreme Court. He describes in detail Sedgwick's activity as a national congressman. The Massachusetts representative, Welch asserts, became a "leader of the second rank," recognized by his associates "as an influential political figure, a capable debator and a tireless committeeman" who ably assisted Washington and Hamilton in obtaining congressional acceptance of their policies. If the Federalists are to be credited with establishing the new government on a solid fiscal and administrative foundation, Welch concludes, then Sedgwick must share in that credit.

In the process of describing these "contributions," Welch presents a balanced view of Sedgwick's political motivation. To be sure Sedgwick was vain and ambitious, but he was also completely devoted to the welfare of the fledgling nation. In fact, his ambitions must be understood in terms of that devotion. Like many revolutionists, Sedgwick believed that republicanism could survive only if knowledgable and disinterested men assumed responsibility for governmental affairs. He was such a man, and it was his duty to make political decisions which the people at large could not intelligently make.

Consequently, Sedgwick had no qualms about fighting Jefferson's election in the House: he knew that Jefferson would lead the nation to disaster, even if the public did not. By emphasizing that Sedgwick acted in accordance with political convictions commonly held by intelligent and respected public leaders in late 18th Century America, Welch has helped to restore the reputation of a man often maligned by unsympathetic historians.

Assistant Professor of History

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Quest for Quality

July 1965 By STEWART LEE UDALL, LL.D. '65 -

Feature

FeatureSidney Chandler Hayward '26

July 1965 -

Feature

FeatureChange and Challenge

July 1965 By HAROLD KING DAVISON '15 -

Feature

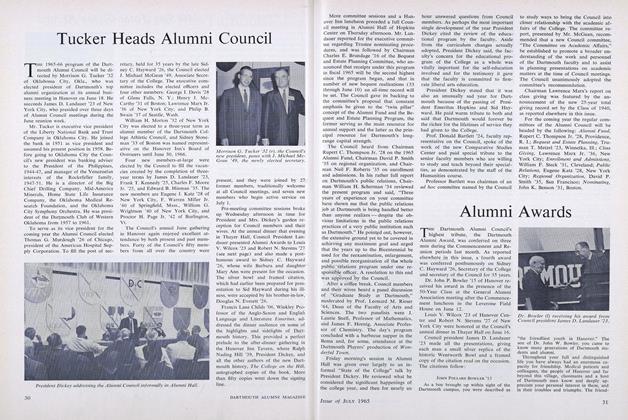

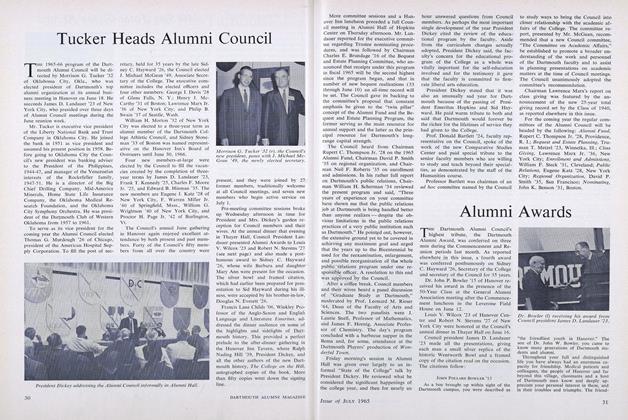

FeatureTucker Heads Alumni Council

July 1965 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1965 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1965

JERE R. DANIELL II '55

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

November, 1924 -

Books

BooksAmerica's Town Meeting of the Air.

April 1936 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

January 1953 -

Books

BooksEDITOR'S PICKS

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 -

Books

BooksSEVENTY DARTMOUTH POEMS.

MARCH 1971 By A. INSKIP DICKERSON JR. '56 -

Books

Books"The Great Adventure"

June, 1926 By F. L. Childs