PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT

A SMITH student told me recently of a Viet Nam teach-in held cooperatively by Smith, Holyoke, Amherst, and the University of Massachusetts. She discussed some of the speakers at this teach-in among them a physicist, a professor of English, and a political scientist. The only trouble was, she said, the physics and English professors kept raising moral issues, and all we heard from the political science professor in reply was power politics.

I think this remark highlights a very serious issue today in American discussions about Viet Nam. If one side is talking only moral issues and the other talking only power politics, then there is no true dialogue. People end up only shouting at each other. As James Reston observed, we are now at the point where "Dean Rusk, the Phi Beta Kappa and Rhodes Scholar, condemns the opposition teachers and students. Joe Alsop calls Hans Morgenthau an 'appeaser'. And Morgenthau calls Alsop's pro-Administration line a scandal."

This kind of polemic is repeated right here on campus. A recent Dartmouth editorial presented us with a dose of robust power politics in regard to Viet Nam. We should evaluate our Viet Nam policy strictly in military terms - the issue of our moral position is irrelevant. And the next day came the inevitable reply in a letter to the editor in which the writer insisted that moral issues should be the primary consideration. To ignore them is to treat the Vietnamese as mere pawns in a selfish power struggle.

I believe we have to talk both power and morals if we are to have a dialogue. And this dialogue is urgently necesary if we are to rescue a rapidly disintegrating sense of purpose in American foreign policy. This purpose cannot be served by a naive self-regarding nationalism that received an apparently only temporary setback with the defeat of Barry Goldwater. Nor can the American purpose be served by an equally naive liberal utopianism that condemns the use of American power and military force almost no matter what the occasion.

I am really appalled when the President of the United States resorts to the crudest kind of flag-waving in order to rally support for his policies. Listen to this sample from a speech Mr. Johnson made to an AFL-CIO conference during the first hectic days of the Dominican crisis. After promising the American flag would go wherever necessary to protect Americans, Mr. Johnson recited from memory these lines he said he had learned as a boy: "I have seen the glories of art and architecture, and mountain and river; I have seen the sunset on the Jungfrau and the full moon rise over Mont Blanc. But the fairest vision on which these eyes ever looked was the flag of my country in a foreign land."

As The New York Times said in another connection, this is the language of 1898 and not of 1965. I earnestly hope and believe that it is not indicative of the real sentiments of President Johnson as he faces the challenges of today's world. I hope it is only an aberration brought on by a moment of stress. But I am afraid it is indicative of the kind of thinking that pervades large sectors of American opinion. At the more sophisticated levels of these sectors of opinion the language isn't so corny, but the naive nationalism is there. It appears, for example, in Hanson Baldwin or Cyrus Sulzberger who urge that we be "realistic" about our position in Viet Nam, that we are not there to help the people of Viet Nam or uphold democracy or anything of that nature, but that we are there simply because we are engaged in a power struggle with the communists. It is, they say, our national interest to be there and has nothing or very little to do with the interests of the Vietnamese people. If that is true, then from both a power point of view and from a moral point of view we had better get out right now.

From the moral point of view we cannot fail to ask ourselves what right we have to use Viet Nam as an exercise in power politics if we are not concerned with the dignity and freedom of the people who are suffering most from the devastation and cruelties of war. From the power point of view, if we are not skillful enough to mesh our interests with those of our allies, the future of our whole network of alliances, including NATO, looks pretty grim. Of one thing we can be certain. Nobody outside our own national. boundaries is going to be willing to die or face the threats of nuclear war merely to benefit the American national interest. We cannot be the leader of alliances nor make good our claim to lead the "free world" unless we have a sense of dedication to that free world and to all the people in it, a dedication which transcends a narrowly, and essentially sentimentally, conceived national interest. I would say again that if we cannot demonstrate satisfactorily that what we are doing in Viet Nam also serves the interest of the Vietnamese people, we'd better get out.

But - I hope we can demonstrate that common interest between ourselves and the Vietnamese and that we will not have to pull out. Those who insist that we agree to withdraw our troops and support before even sitting down at the negotiating table - and that is the present demand of the North Vietnamese Government and Red China - should realize that this means turning over all of Viet Nam to a communist regime. Anyone who knows anything about the nature of communist regimes knows that such a fate will not be a pleasant one for the South Vietnamese. Thousands and probably tens of thousands of human beings who have exposed themselves in the long struggle and who have risked a great deal in order to stand against communism and with us will be exposed to terror and the mercies of a police state. Those who so strongly stress moral rectitude in international politics should therefore realize that they take on a grave moral responsibility when they urge us to pull out of Viet Nam.

I think we should be clear whom we are fighting in Viet Nam. The Viet Cong is made up of a mixture of rebels, indigenous to South Viet Nam and some of them non-communist, and a central and dominant core of communists who are directed by Hanoi and Peking. Should the United States pull out, there is no question but that South Viet Nam would be taken over by the Ho Chi Minh regime. We would be turning over the Vietnamese to a tyranny far more efficient and ruthless than the admittedly unlovely series of governments which have so far ruled in Saigon.

And here is perhaps the greatest paradox of all. Those in this country who are so vociferous in their demands that the United States quit the war in Viet Nam seem to overlook the fact that they thereby argue for an extension of communist rule. Indeed, they seem to regard the United States as the sole villain in the piece and are so eager to point out the flaws and weaknesses of American policy that the Viet Cong by contrast come off looking positively heroic.

One of the most ironic, disturbing and potentially tragic of recent developments is that certain people have suddenly begun to establish linkages between the civil rights movement in this country and the "quit Viet Nam" philosophy in foreign policy. They imagine that the great achievements of Negroes and whites in non-violent social protest in America can be transferred from a domestic political society where law restrains violence to the international society where force unhappily still has primacy over law. They begin to protest against American policy in Viet Nam with the same vehemence and the same techniques which have been used so justly to protest the absolute injustice of racial discrimination. In so doing they begin to confuse enemy and friend. In international politics the enemy is and remains alien tyranny, and whatever the sometimes hopeful changes which have recurred in recent years, communism represents the chief and most powerful embodiment of that tyranny. Anyone who stands for the principle "one man - one vote" should remember that the communist system hasn't had an honest election since it first emerged in Russia nearly fifty years ago. Anyone who stands for racial equality should know that Communist China is the most skillful instigator of racial hatred in the world today. Anyone who admires the principles of non-violence should recall that violence is the officially endorsed instrument of social change and international policy in the communist orthodoxy; and that violence has been the official policy and practice of North Viet Nam for the last eleven years, some ten years and ten months before American bombs began to fall on North Viet Nam last February.

The civil rights battle in this country and the struggle in Viet Nam are two different kinds of conflict in two very different contexts. The enemies are different and the techniques to deal with the enemies must be different. It is time to disentangle these two great issues before serious damage is done. If we can disentangle them I think it will help to reestablish that dialogue of which I spoke at the outset. It will also help reestablish that sense of purpose in America both at home and abroad which is today in danger of being torn apart by the so-called hawks on the one hand and the so-called doves on the other.

Naive and egotistic nationalism and power politics cannot be the answer we need. Neither can naive and quasi-pacifist moralism. We need to recreate that marriage of power and moral purpose that has made America a truly benevolent force in world politics at those times when we could launch a Berlin airlift, a Marshall Plan, a Point Four Program, an Alliance for Progress, and a Peace Corps in the conviction that Americans were serving something larger and more meaningful than simply themselves.

Leverone Field House, in its first use for graduation exercises, easily accommodated more than 5,000 persons.

Dean Dickerson dispensing diplomas to one of the two lines of seniors.

5,000 seats on Baker's lawn remainedempty as Commencementwent indoors on Sunday morning.

Professor Sterling's remarks on U. S. policy in Viet Nam were made at a May 6symposium in which six members of theDartmouth faculty participated. This Dartmouth version of the "teach-in" was sponsored by the Undergraduate Council andwas attended by a large student and facultyaudience.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Quest for Quality

July 1965 By STEWART LEE UDALL, LL.D. '65 -

Feature

FeatureSidney Chandler Hayward '26

July 1965 -

Feature

FeatureChange and Challenge

July 1965 By HAROLD KING DAVISON '15 -

Feature

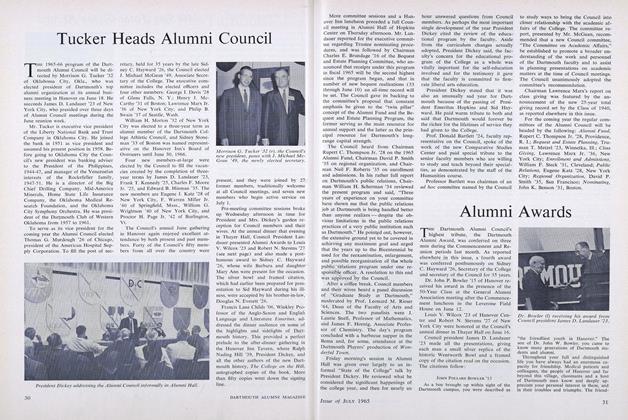

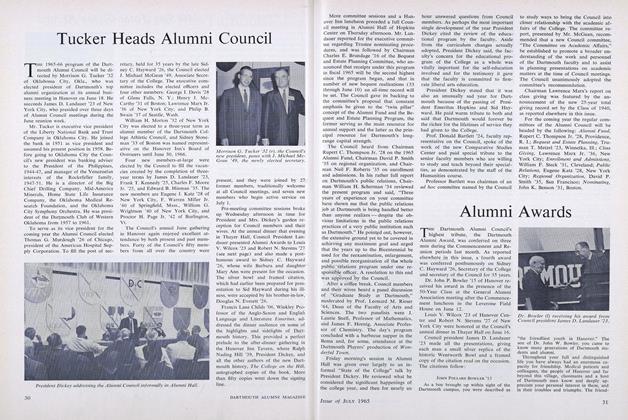

FeatureTucker Heads Alumni Council

July 1965 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1965 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1965

RICHARD W. STERLING,

Article

-

Article

ArticleDuring the first week of February public announcement was made,

February, 1909 -

Article

ArticleMade Welfare Director

June 1934 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Award: Mark H. Smoller '53

June 1993 -

Article

ArticleAn Answer to Pres. Hopkins

MARCH, 1928 By C. W. Barron -

Article

ArticleCommencement

June 1979 By James L. Farley