In the modern world, technology and economics have taken on roles of growing importance

USA (Ret.), LL.D. '62

IN the affairs of men, power has always been used to persuade. Let us examine power, especially its changing character today, and then relate it to persuasion and to peace.

Usually we think of power in terms of military power, and most of us have long considered this to be the primary source of power in world affairs. Of course, to exist, military power must have a base of economic support. In all past experience only a society that had the natural resources and, in addition, the inventiveness and industries to produce modern weapons systems could bring them to combat and thus gain a decision in international conflict. Hence, from history we are inclined to think of military power as the dominant force, and the economic power which supports it as & secondary source of military strength.

Within our memory, and at a time when the earth was less densely populated than it is today, military power was used for economic aggrandizement. A powerful and aggressive nation could add to its strength by taking the resources from others. In an excellent and comprehensive book, Power, written in the 1930's, Bertrand Russell expresses it this way: "Economic power, unlike military power, is not primary but derivative." He then went on to illustrate how military power had been used to seize vast colonial empires from which great wealth could be extracted; wealth in minerals, oils and arable lands, for example. The nation that could seize the most resources could, in the long run, develop the most powerful military forces.

I believe there is a fundamental change taking place, and indeed it has taken place, in this relationship between military and economic power. Fundamentally, today technology can, if wisely directed, provide adequate resources for humans to live comfortably on this earth. At the same time, technology can, if so exploited, provide the weapons systems to destroy a major portion of the human race. Finally, technology is having, and will continue to have, such a tremendous impact on world affairs that it is changing the balance between economics and military power significantly. It is this change that I would like to examine.

Before doing so, let me call your attention to the talk given by Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara in Montreal on May 18. He referred to the sources of unrest and discontent around the world, emphasizing the fact that security means economic development, not military hardware. In fact, he stated flatly that in his opinion the concept that military hardware is the exclusive or even the primary ingredient of permanent peace in the mid-twentieth century is absurd.

During the past twenty years I have been closely associated with the use of military power, the planning and execution of national military policy and, to a lesser extent, the conduct of foreign policy. To say that it has been an extremely active environment is an understatement for we never have had such amounts of power available nor have we had so many problems associated with its use. Never has there been such widespread interest in our many commitments and involvements abroad nor so much social turbulence at home.

HAVING been in the vortex of much of the discussion, I find it deeply disturbing that we have yet to get to the heart of the matter. To do so we must understand, and explain, in much clearer terms than we have so far, our total diplomatic and political power; for this is the power that persaudes: the economic, technological, and military components of such power. Part of this examination will be a consideration of the role that each of these will play in our national strategy.

Actually, we have been doing very well in the realm of economics and technology, especially during the past decade. It is in the area of applied military power where most of the misunderstandings and frustrations seem to exist. In order to understand what is causing them, I believe we should begin with the meaning of the most significant military event of our time - the detonation of the first nuclear weapon.

It began at fifteen minutes past eight the morning of August 6, 1945, when Fat Man detonated over Hiroshima. The electrical impulses fired the lenses, providing a heat and shock wave that moved uniformly to the core, and this fissioned as predicted. There were no technical surprises for the scientists, but the moral shock and the emotional upheaval in the wake of the bomb have never subsided. There were over a quarter of a million killed and wounded and hundreds of thousands harmed for life. The shock waves from the Hiroshima blast went far beyond those predicted by the nuclear physicists. They traveled far, both in space and time. Nothing in our country's history has had a comparable impact upon foreign policy and military affairs. Governments have fallen, coalitions of nations have been formed and reformed to cope with the problems caused by the bomb's existence. The bomb was at the heart of De Gaulle's rejection of Great Britain's desire to join the European Common Market. The bomb was ever present in the mind of President Kennedy and his advisers at the time of the Cuban missile crisis. The bomb today casts a long shadow over all discussions on the future of NATO. For the fundamental nature of military power changed with the advent of the bomb.

Few realized in 1945 that the bomb was the beginning of the end, if not indeed the very end, of man's search for energy to be used as military force. The more prevalent view was that a new era was born — the age of atomic force. Now, twenty years later, we understand better the place of the bomb in the spectrum of history. It was the end, not the beginning of an era. It was the end of man's search for force and it marked a beginning of a new quest — the search to find new ways and means of influencing the behavior of other humans. It was to be the age when the earth would shrink rapidly due to high speed air travel, space exploration, satellite communications, and rapid data processing systems. More and more the nations of the earth were to consider themselves part of one large world community; the logical end of an evolutionary process that began many thousands of years ago with the family, tribal and city-state groupings.

IN the armed forces the physical effects of the bomb alone made plain for all to see that all the boundaries between the traditional arenas of combat, land, sea, and air, were wiped out. And as our military men turned to past experience for answers to deal with the new problems of the day, they did not find them. For the answers were not to be found in a remembrance of things past; they could be found only in a thoughtful analysis of the future, in a profound search for the meaning of the period we were about to enter. The classical military formula of escalating power until total victory would be achieved was to become absolutely meaningless. For wars, if there were to be wars,and the means that would resolve them, were going to bemany orders of magnitude different from what they had been in the past.

In 1950, five years after the end of World War II and Hiroshima, Soviet-equipped North Koreans invaded South Korea. It was a costly experience for us. Possessing the most powerful military establishment in the world, well equipped with nuclear weapons, we suffered over 140,000 casualties and had to accept terms less than victory. Yet, despite the Korean experience our national strategic policy in the mid-fifties was still based on massive retaliation. Admittedly there was much argument and discussion about the validity of this view. Indeed, our Promethean achievement seemed to have left us in intellectual disarray.

From the mid-fifties on, our total power seemed to paralyze our intellectual processes, and our response to challenges of lesser magnitude than total war were of a diminishing degree of credibility. This was because a number of myths prevailed in our thinking, and they stemmed from a tendency to look inward to our experience rather than to postulate technology and political trends into the rather clouded and hazardous unknown of the future.

The first myth is that war is a continuation of politics by other means. This Clausewitzian orthodoxy holds that wars will be fought and won, and sufficient power will be applied until they are won. Then war will be followed by peace, a period in which politics as usual would be the preoccupation of the world powers. This, in turn, very likely will be followed by a period of war, and the difference between the two will be quite discernible. I believe by now that most of use realize that this no longer is true. In his talk in Montreal, our Secretary of Defense pointed out that in the past eight years "there have been no less than 164 internationally significant outbreaks of violence, each of them specifically designed as a serious challenge to the authority, or the very existence, of the government in question. . . . And not a single one of the 164 conflicts has been a formally declared war." From this experience, realistically, we must conclude that wars will not always be declared and that nations will not always commit their total resources to win in every confrontation. There will be wars that are not wars, if defined in terms of our experience before Hiroshima. In fact, it may be wiser to keep a shooting war limited and undeclared while pursuing national goals by other means, never admitting the existence of a war nor indeed a desire to bring it to an end.

The second myth is that if you destroy enough people and enough property you will overcome an enemy's will to resist. A corollary to this is that a nation should use as much force as necessary to win since in war there is no substitute for victory. Actually, the nature of conflict being what it is, and the danger of a nuclear holocaust being ever present, it is compelling that solutions less than total war be found. At the same time, the communications media have brought more knowledge about the conduct of war into every home. The inevitable, and needless, loss of civilian lives has become the subject of concern to more than just the contending military forces. Thus, sensitivity to public opinion has made it necessary to consider restricting attacks to military targets whenever this is possible, unless, of course, the nation's goal is to seek total war.

A third aspect of existing military thinking deserves mention. The thought still persists in many minds that the ultimate in sophistication and usefulness in weapons systems is the high-yield megaton bomb delivered by missile or aircraft. By its very nature it is believed that it should be able to cope with almost any threat to our survival. The fact is that it is the very effectiveness of our Strategic Air Force and the overwhelming, devastating potential of H-weapons that prevents their employment in a conflict other than total war. And again, it is the devastation that would be caused by the use of these weapons by the strategic air arm that has given tremendous emphasis to the role of the other Services - those that have it in their ability to apply power with discrimination, flexibility and restraint - and has given equal emphasis to the need to find and understand the uses of other forms of power stemming from our science and technological programs and our great economic strength.

I would like to conclude this comment on military power by emphasizing that the changing nature of conflict today makes it imperative that we develop better means of dealing with limited wars, guerilla wars, and types of conflicts we cannot yet anticipate with accuracy but that will not be total war. Studies in these areas will require great effort not only in anticipation and planning, but in research and development as well. This will require a productive, burgeoning, dynamic economy. How well have we been doing in the realm of economics?

MOST will remember that after World War II the Soviets anticipated an economic collapse of the West, believing that our economy was entirely based on war. What we have accomplished has been truly remarkable and during the past twenty years our economy at home has expanded at a tremendous rate. It is vital that we sustain this growth. In this year of 1966 our Gross National Product will be in excess of $700 billion. This is about ten times what it was in the mid-thirties. Our industry is doing very well. During the decade beginning in 1955 combined annual sales of the 500 largest industrial corporations increased by $100 billion (from $161 billion to $266 billion). Corporate profits last year, for example, before taxes were $73 billion, an increase of $9 billion over the previous year. Per capita income reached $2700 last year, a 6% increase over 1964 income. Personal income was a record high of $528 billion, an increase of $35 billion over the previous year. Between 1935 and 1946 annual personal income about tripled, from $60 billion to almost $180 billion. It increased another $700 billion between 1948 and 1955.

These are impressive statistics. We should have no apprehension whatsoever about the outcome of any economic competition with the Communist countries. Our apprehension, if any, should be concerned with whether or not we use our resources wisely and well, to provide a good society at home, to aid the emerging young nations abroad, while at the same time we provide our armed forces with weapons systems adequate to meet the broad spectrum of challenges that will confront us.

One of the most remarkable and far-sighted programs ever undertaken by any country was the inauguration of our foreign assistance program in 1949. It enabled us to provide economic assistance, wherever it could be properly used, to the newly emerging nations as well as to many of the older powers. In 1949 this program amounted to a little over $4.5 million and was 1.74% of our Gross National Product. It has been overwhelmingly successful; today South Korea, Taiwan, and Indonesia, for example, all are monuments to the achievements of this program. In addition, a country geographically almost a part of the Eastern bloc, Yugoslavia, was able to achieve economic prosperity and retain its political independence from Moscow. Indonesia is the most recent dramatic example of how people can help themselves, and throw out the Communists while doing so, with little assistance from us.

Our foreign aid program has been overwhelmingly successful in areas where the Communists can least afford to have us succeed. In areas where they would like to accuse us of colonialism and, indeed, do accuse us of economic colonialism today, we have been able to give many countries an unprecedented standard of living, far superior to anything that the Communists could offer them. This has been accomplished despite the fact that we have steadily reduced the amount of foreign aid until today, in 1966, it is but .48 % of our Gross National Product compared with 1.74% at its inception in the late 1940's.

There is an old combat maxim that one should reinforce success. I would like to point out that in speaking at Boston University recently Lady Jackson recommended that the "have" nations such as the United States contribute 1% of their Gross National Product to help the under-privileged and under-developed countries. Some attribute our unwillingness to do so to the cost of the Vietnam war. If so, this at least raises the question of whether or not we may now be following a course inimical to our long-term strategic interests.

Another area in which Americans have achieved great success has been in the exportation of products and business know-how. Our exports, which amounted to approximately $37 billion in 1950, have grown to well in excess of $100 billion in the mid-sixties. Our direct investment has increased from $25 billion to $50 billion in the same period of time. In addition to this direct investment, we have indirectly invested $20 billion through stocks and portfolio holdings. Our direct investment abroad is now increasing at an average of more than $10 million a day. With this investment we have exported entrepreneurial skills and management know-how that have proven to be very attractive to the Western World. So successful has this been that the return on our investment abroad today amounts to $4 billion annually.

This has all been possible because of a burgeoning economy at home and the aggressive drive of our businessmen to find markets and business opportunities abroad. At the same time they have sought to raise the standard of living wherever they have marketed their products and services. In this they have been, by and large, very successful. There is nothing that the Communists have done, or so far can do, that can compare with this. It is with great uneasiness, therefore, that thoughtful businessmen consider restrictions on the flow of dollars overseas. For the export of our entrepreneurial skills and products has been one of the most successful undertakings in foreign affairs in the history of our country, and the most productive of good in our confrontation with the Communist bloc. In extension of this, I personally think we should step up East-West trade as fast as we can.

I HAVE discussed military power in some detail, and also our economic power. I have noted the views that prevail, particularly in the use of military power, and the great importance of our economic power. It is my deep conviction that a fundamental change is taking place in the nature of global conflict. An understanding of this change, together with the development of strategy and tactics that reflect this understanding, is the greatest challenge that we face today. Nuclear weapons, and the nations possessing them, will increase in number despite any efforts we make to limit both. And the terrible power contained in these weapons will continue to chill the hearts and strike fear into the minds of those who know them. At the same time highly skilled forces, equipped with the most sophisticated weapons that modern technology can provide, will continue to improve their capability to deal with limited wars, guerilla conflicts, and political upheavals of the many varieties that comprise conflicts less than total war. Concurrently, science and technology will give man the resources with which to exploit all that nature has given him in abundance on this earth. To an increasing extent our economic endeavors will give us opportunity to eliminate the causes of war and make clear our capacity to win a total war if it does occur.

It is imperative therefore that we recognize the strategic importance of both technology and economics. For if we continue to conduct our economic programs well, and use our resources wisely, we shall do well indeed. The greatest danger is that we may through miscalculation allow ourselves to become inextricably involved in a tactical confrontation that will drain our resources to such an extent that our economic and science and technological programs will suffer critically. This perhaps offers the greatest challenge that we shall know in our time, the challenge of the war that will not be a war, the challenge of a war in which we may, if we do not grasp the meaning of these relationships, become so inextricably involved that we could be grievously hurt in the other areas where we have been so overwhelmingly successful. To deal with this type of confrontation, and involvement, will take great wisdom and patience and, above all, understanding on the part of each of us.

GENERAL GAVIN'S ARTICLE is adapted from the talk he gave in Hanover, June 14, at the symposium on world affairs sponsored by the Class of 1935 during reunion week. His talk served as the basis also for the lead article in the July 30 issue of Saturday Review. General Gavin, a famed paratroop commander in World War II, served as Chief of Army Research and Development, and after his retirement was named U.S. Ambassador to France by President Kennedy. He is the author of Airborne Warfare (1947) and War andPeace in the Space Age (1958). General Gavin now is chairman and chief executive officer of Arthur D. Little, Inc., management consulting firm in Cambridge, Mass.

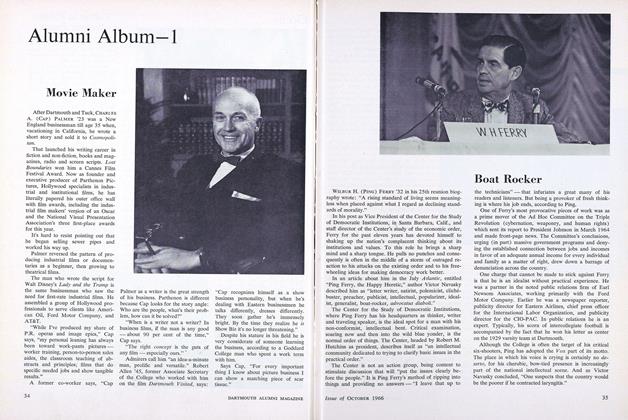

General Gavin and Frank Cornwell'35, moderator, at the Class of 1935symposium held during reunion week.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Features

-

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Form Association

November 1957 -

Feature

FeatureFEBRUARY'S BIG EVENT: The Hopkins Dinner in New York City

January 1958 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Council Has Record Attendance

March 1958 -

Feature

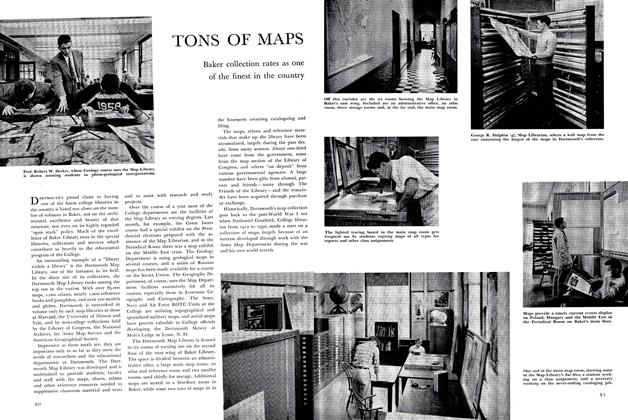

FeatureTONS OF MAPS

December 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

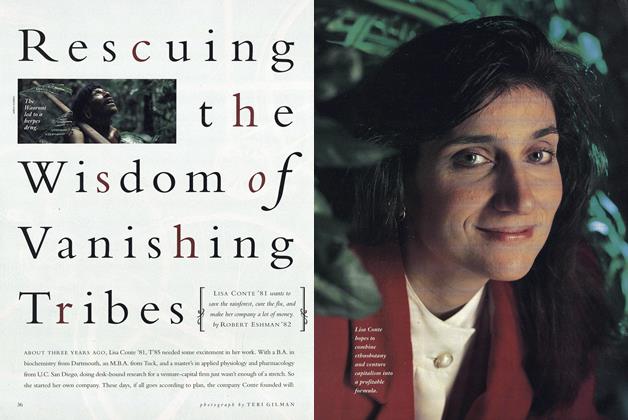

FeatureRescuing the Wisdom of Vanishing Tribes

June 1993 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureA Heritage and An Obligation

JULY 1964 By SIGURD S. LARMON '14