The nobly insolvent busi-ness of signing up im-portant books and goodauthors

Losing money is what university publishing is all about. That's why we exist," says Thomas McFarland, director and editor of the University Press of New England. Scholarly publishing, he explains, is subsidized publishing. Scholarship never a money-making enterprise has always depended on the generosity of patrons. In the Middle Ages, liberal-minded monarchs and nobles underwrote the universities where scholars were gathered; nowadays it is apt to be governments and foundations but the basic economics are unchanged.

The growth of knowledge is exponential when scholars can communicate about and build upon (instead of duplicate) their individual efforts, but such communication was haphazard as well as expensive until moveable type and printing presses appeared in the West. That happened in the middle of the fifteenth century, and university publishing followed hard on its heels: the first university press was estab lished at Oxford in 1478.

Four centuries elapsed before the baton was taken up in this country, and it was Cornell that did it, in 1869. Nine years later, a second American press (the oldest continuously operating scholarly press in the country) was set up at Johns Hopkins University. At the founding of that press, Daniel Coit Gilman, president of Johns Hopkins, articulated the philosophy behind university publishing: "It is one of the noblest duties of a university to advance knowledge and to diffuse it not merely among those who can attend the daily lecture but far and wide."

It is, according to McFarland, a modern version of patronage. "Good research needs to be published and disseminated so others will benefit from it," he says, "and in almost any intellectual community there is a feeling that a university press is nearly as important as a library."

McFarland goes on to explain that at the University Press of New England (UPNE), the average scholarly book contains 280 pages, has a print run of 1,200 to 1,500 copies, costs about $9,000 to take from manuscript to warehouse, requires $2,500 to promote, uses up some $11,OOO in over head, and brings in about $18,500 in sales. That all adds up to a $4,000 deficit. Subsidies come from a variety of sources the author's institution, a scholarly society, a foundation, a business community, even occasionally another institution where a scholar with clout takes up the cause of something UPNE wants to publish. Authors often do their bit, too, by forgoing royalties. (Tenure hopes and tax write-offs play some part in such sacrifices, of course, but the most frequent motive is a desire to get the publication out to other scholars at an affordable price.)

The Association of American University Presses (AAUP) currently lists about 80 members, some of them large (to the tune of a hundred books a year and sales of several million dollars) and most of them not. Some 40,000 new books are published each year in the United States, and nowadays one out of twelve of them issues from a university press. That is barely eight percent, and it represents only one and a half percent of the industry's total annual sales. But one book in six today bears a university press imprint, because university press books remain in print far longer than the general average. Their cultural impact is high, too: 31 out of the 159 National Book Awards made from 1950 to 1979 went to scholarly press publications, and if we exclude those prizes awarded to fiction and children's books (which university presses do not generally publish), then the number jumps to 31 out of 117: 25 percent of the awards to eight percent of the books.

Most of this country's scholarly presses were born, strange to say, during the hard-pressed thirties and forties. The sixties represented a peak of good times for them, an era during which the national consciousness about education was high and funding subsidies were easily come by. But the seventies, says McFarland, were tough.

It was in the seventies that Dartmouth took the plunge into university publishing. Its venture began in 1967, when Edward Connery Lathem, newly appointed librarian of the College, initiated an inquiry into the state of publishing at Dartmouth. The College's publishing interests were at that time confined to a part-time operation known as Dartmouth Publications, a small enterprise that reported administratively to the librarian. It was issuing only Dartmouth-oriented titles widely varying in nature and format. "At the time," explains Nanine Hutchinson, marketing manager at UPNE, "that was the only sort of thing the administration wanted, although a feeling had been building that the College should move beyond inner-directed publishing. Its professors were writing fine books and publishing them elsewhere, and by then Dartmouth was the only Ivy League school without a press."

Lathem arranged for Thomas Wilson, director of Harvard's university press, to come to Hanover in the autumn of 1967 and assess the situation. Wilson's recommendation was startling but provocative: he suggested that in order to hold down costs and avoid the creation of yet another small, marginal press, Dartmouth should consider banding together with other New England institutions of higher learning in a joint publishing arrangement. He suggested further that the College seek advice from one of its own the man who had in 1963 set up the first scholarly publishing consortium in the country, Victor Reynolds '27, former director of the Cornell University Press and recently retired director of the statewide University Press of Virginia.

Lathem contacted Reynolds, a skilled veteran of both university and trade publishing whose devotion to publishing seems to have been matched by his devotion to Dartmouth. Fascinated by the idea of an interstate consortium at his alma mater, Reynolds agreed to come out of retirement to set it up. Then followed a long and rather painful period of deliberation. (Academia, as Lathem points out, is immortal and takes forever to do anything.)

It was not until 1970 that Presidentelect John Kemeny made the first concrete move toward a university press of New England by contacting President John McConnell of the University of New Hampshire. Barkis was willin', and in April of 1970, the Dartmouth College Board of Trustees approved the establishment by Dartmouth and the University of New Hampshire of what has become a very successful experiment in publishing.

The original intent was to incorporate colleges and universities from Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire as a University Press of Northern New England, but when institutions in Massachusetts and Rhode Island expressed interest, the "northern" was dropped. Within a few months, Reynolds had signed up Clark University and the University of Vermont, and in time, 0Brandeis, the University of Rhode Island, Tufts, and Brown would join, to give the press its current composition.

Like most university presses, UPNE has two governing boards, one to handle policy and fiscal matters, and the other to handle editorial decisions. The director and the staff are salaried, but both boards are volunteer bodies. The Board of Governors is composed of ranking administrators (usually deans of graduate schools), one from each member institution. Each school also sends one senior faculty representative to make up the Editorial Committee, which decides what manuscripts to accept and thus controls the imprint. The members of the Editorial Committee also serve on their respective campuses as heads of panels that solicit and screen manuscripts. (The newest member, Brown, has gone the extra mile and appointed a professor to serve part-time as its own local editor, charged with acquiring manuscripts for Brown to submit to UPNE.)

The press operates out of the central office and a 16,000-square-foot warehouse, both located in Hanover. Payroll administration and accounting support are provided by Dartmouth, which in that sense hosts the press and enjoys its presence locally. At present, UPNE employs a staff of 10, backed up by a number of free-lance editors and designers. It performs its own ware housing and distribution, though it contracts for such services as copy editing, printing, and binding. It offers full publishing services to its eight member campuses and also to authors at large. Roughly half of the 30 or so books it publishes each year come from member institutions, half not.

Under its own imprint The University Press of New England it publishes those books for which its authors and its staff locate the required subsidies. When a member institution sponsors a publication, a joint imprint University Press of New England for Dartmouth College, for instance is used and a percentage (usually half) of the income from the book goes to the institution. The cost of running the press is shared equally by members, who pay an annual membership fee that has no connection with the number of manuscripts accepted from each institution. At present, the UPNE membership fee is $16,000 a figure that causes people to ask McFarland if he hasn't dropped a digit.

According to one of its brochures, UPNE publishes "important works in all subjects and areas of scholarly endeavor, including books concerned with the life and culture of New England." Indeed, there is at UPNE a fair amount of regional specialization, accounting for about a quarter of its list, though as the press's financial officer, Thomas Johnson, says, "We have no desire to be known solely as a publisher of New England books." What UPNE is also not, McFarland emphasizes, is a "service" press: "We don't publish what any university president tells us to publish. We do not operate as a service outlet for manuscripts originating from our member faculties. Every manuscript, regardless of its origin, passes the same evaluation process; the New England imprint is controlled by the consortium board."

McFarland points out that one interested university recently decided against joining UPNE because it did not want to relinquish sole and ultimate authority in deciding what is published from that campus. The sacrifice of that absolute autonomy is amply offset, McFarland feels: "The consortial action brings consistently high standards and creates a healthy, competitive spirit among our members to submit manuscripts of the highest quality." Nor, he says, has there ever been during the five years he has been director a situation in which one member of the Editorial Committee felt strongly about publishing a manuscript that had been rejected by all the other members. An impressive system of checks and balances works to prevent such an impasse. Manuscripts are first screened locally by committees of editorial scouts on member campuses, and then each is sent out for review to two readers in relevant fields. Then it comes before the Editorial Committee. "After all that," explains McFarland, "the evidence is usually conclusive."

The current list at UPNE includes some 275 titles in 26 classifications, from African studies through such categories as biography, Jewish studies, law, music, politics, and religion all the way to sociology. It almost never publishes in the hard sciences few university presses do, largely because the intensely specialized and time-conscious scientific community prefers to publish in journal form. Except in translation, UPNE does not accept fiction either. "That," explains McFarland, "would require an entirely different kind of editorial evaluation." Nor, says McFarland with a slight shudder, does it publish unrevised dissertations. "We publish Festschriften and conference proceedings very selectively and textbooks only if they are upper level or groundbreaking no undergraduate texts." The press also distributes books for several nonprofit institutions such as the New Hampshire Historical Society and the National Gallery of Art.

UPNE also publishes a number of what are called "trade" books most- ly serious but unspecialized non-fiction sold through general bookstores and intended by virtue of its greater audi- ence appeal to help carry the less wide- ly-marketable scholarly works. Two such books recently put out by UPNE are a reissue of David Bradley's NoPlace to Hide, an eyewitness report of early atom bomb tests at Bikini and a still entirely relevant analysis of the dangers of nuclear weaponry, and Herb Garden Design by Faith Swanson and Virginia Rady, a comprehensively illustrated how-to book.

UPNE expects, as do many university presses, to issue more trade books if funding continues to be scarce, though, as Hutchinson points out, there is a ceiling on the percentage of such books a university press can deal with not only with regard to mandate, but also in terms of efficient allocation of resources. "We can't handle too many," she says. "Their promotion takes more time than the promotion of scholarly books." Nor is it likely that UPNE will ever try to publish the kind of best seller that has massive popular appeal: "We don't do Hollywood technicolor promotion. We wouldn't want a Garfield that's the kind of publishing that relies on market research and seeks to publish what people will buy instead of what needs to be written. University press people are an idealistic lot. We don't mind working hard for a 1,500-copy printing of a good book that scholars need."

Which is a good thing, given just how difficult the past decade has been. In 1973, the perilousness of the times sparked a meeting of university press directors with people from the National Endowment for the Humanities to discuss the problems beseting scholarly publishers. That meeting led to a National Enquiry into Scholarly Communication, conducted from 1976 to 1978. The enquiry committee reported that scholarly publishing was then concentrated in a relative handful of institutions: out of some 1,500 universities and four-year colleges, 35 had presses. Of those presses, nearly half were small, with annual sales of no more than $500,000. Larger presses were cutting back and smaller ones were just plain tottering.

The report had some helpful suggestions to offer, all along the lines of standing united to prevent falling divided: small presses could hope to ease the funding crunch, it said, by buying some of their services from larger presses, by forming consortia (a difficult arrangement, according to the report), or by merging "in those cases in which collaboration and consolidation seem desirable for the entire range of press functions." UPNE was held up in the report as a model to be studied: small presses were exhorted to strengthen themselves by establishing consortia "along the lines of the University Press of New England," and institutions without presses were urged to subsidize publications or join in consortia such as UPNE.

The existence of university press consortia is in itself, of course, testimony to the creative powers of necessity, and the idea, as Wilson had pointed out to Dartmouth in 1968, is probably the wave of the future. To date, however, there are only about a dozen in operation, most of them marketing consortia only, in which each member maintains a distinct editorial office. Among those whose editorial and marketing functions are centralized, only UPNE crosses state lines.

There must be some flaw in the I scheme," said a publishing colleague of McFarland's but to date it hasn't surfaced. Not that things haven't been appropriately rough at times, as Reynolds' successor, David Home, recalls. Home, who served as the director of UPNE from 1972 until he retired in 1979, speaks candidly of the threat posed by campus politics: "There is a potential conflict in such a consortium between two principles devotion to scholarship on the one hand, and on the other the really conflicting tug on the part of each institution to do as much as it can for itself, regardless. That could have meant open conflict." The fact that it never has is both remarkable and inspiring.

Directing such an operation, according to Home, is "a matter of linking money issues to the nebulous scholarly qualities we are all after." He explains that the administrations must think about money, must ask themselves questions such as how many faculty will benefit for the amount of money being spent, He sees the director of UPNE as a translator between the administrations and the faculties (the authors), explaining the positions of each to the other. "All the member institutions must be kept informed and satisfied that the press is being run the best way for them and for scholars in general. That requires some caretaking, and each member may require a different sort of care." For Home that meant going to the different campuses and meeting people, trying to help get things started on a campus that wasn't publishing much, making sure that one institution did not take over to the extent that those who were not publishing just then would become apprehensive. "It was largely keeping peace in the family," he admitted.

There was a bit of a flap when the university that wanted to retain editorial autonomy had to confront and be confronted with the fact that that was not possible at UPNE. Another difficult time involved an institution that appeared very interested in joining, but kept putting it off and sending strangely veiled replies to the press's inquiries; the problem there turned out to be an obstructive campus clique afraid of losing its local publishing prerogatives. In the end, neither of those institutions joined. Home also recalls one attempt by a member to weild undue influence on the Editorial Committee, but he reports that even in that instance, the principles of scholastic merit arid cooperation on which the consortium was founded prevailed in the end. And they have continued to do so, allowing McFarland to describe UPNE recently this way: "There is an occasional dissonant note. But politics and self-serving motives seldom obstruct our vision. Indeed, we have safety in numbers: with eight members holding equal owner ship, we are less vulnerable to the whims of a single university dean or provost who may lack experience in or commitment to scholarly publishing."

The press has come a long way during its 14 years. Hutchinson, who came to UPNE in 1973 from a position at Harvard University Press (which had just broken the million-dollar mark in annual sales), recalls the panic of her first day on the job. "It was a Tuesday, and I was set to typing invoices. I typed only four all day, $43 worth! I thought, 'My god, I've made a mistake. How can they even pay me?' " From those days, when there were about ten books on the backlist and one in the pipeline and the warehouse was a room in the basement of College Hall that flooded regularly, UPNE has grown to its present thriving situation. When AAUP published in 1982 a statistical survey of its members, UPNE stacked up very well indeed compared to other scholarly presses. The survey allowed McFarland to write this glowing report about UPNE's finances: "Our operating expenses, calculated as a percentage of sales income, are more comparable to the large presses than to the small, even though our sales volume is but a fraction of that at the large presses. Sales income per staff member is the same as that at large presses, and double that at the small presses. We publish 3.8 books per staff member; the industry average is 1.9."

Part of this success is attributable to the way UPNE has embraced the new technology available to publishers. "The biggest job I had to tackle when I got here in 1981," explains Johnson, "was computer functions. There was some software for order-reporting in place, but it was slow and cumbersome and a lot of reporting was being done by hand. I threw myself into order-processing software, and after four or five months of midnight oil, I felt comfortable. Now we use the Dartmouth College computer for almost everything. Within the next year, we will buy some sort of personal computer for budgeting, scheduling, and word processing but not for order processing. That's, just too big a job."

McFarland himself cites "the rich resource of the College's expertise in computers" as one of the greatest benefits of being based in Hanover. "The new technology is changing the way books are made," he says, explaining that the number of computer produced manuscripts that UPNE encounters is increasing, and as soon as the process of translation from personal computer to typesetter is improved, it will be possible with manuscripts as well as promotional brochures to edit until the last minute and get galleys two hours after transmission.

Hutchinson is also enthusiastic about computing. "The computer science people are so sharing around here," she says. "They come and help us figure out how to do all sorts of things." She is particularly excited about the Book Review Editors' File that UPNE has decided to develop with a grant recently received from the Hewlett Foundation. "It's a nifty thing a countrywide database by subject heading of journal information (book review editors' names, current addresses, publishing profiles, reviewing practices). Every university press will be able to access the data when it's time to choose where to send out review copies. Right now each one of us is digging out that information separately, duplicating efforts. It's an astounding project for a press our size."

Design has long been a forte at UPNE. The press has been winning awards for it steadily since 1975, when John Duffy's Early VermontBroadsides won the American Institute of Graphic Arts Book Show award. Its latest showpiece, John Dryfhout's elegant volume The Work of AugustusSaint-Gaudens, last year won the American Association of University Presses Book Show award and brought the total of UPNE's design citations to ten. That same book also received kudos for editorial merit, in the form of the Wittenborn Award from the Art Libraries Society of North America, and it appeared on Choice magazine's Out standing Academic Book List. Nine other editorial citations have come UPNE's way as well, celebrating publications such as Cecil Schneer's TwoHundred Years of Geology in America (1979), the Bibliographies of New England History series and Frank Small wood's timely book The Other Candidates (1983).

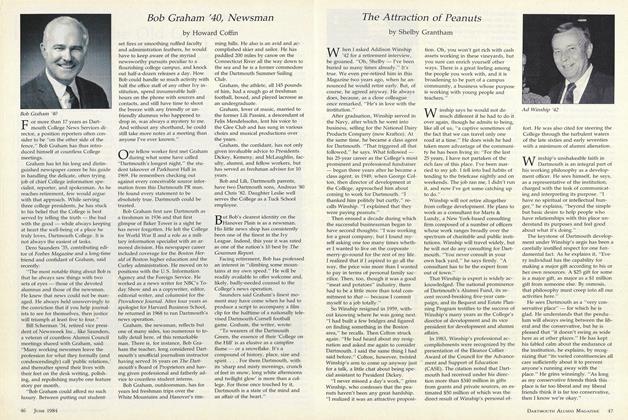

UPNE's free-lance designer Joyce Kachergis made a mark in the advertising sphere as well, when a series of 15 ads she designed for the New York Reviewof Books won an award in the University Press Ad Campaign competition. Reprinting activity is another index of publishing success, and UPNE is no slouch there either: this past fall saw three second printings, two third printings, one sixth printing, and an eighth printing (of the press's popular experimental text, Demotic Greek, by three Dartmouth faculty members).

Such testimonials to good fiscal management and quality have led also to the loosening of purse strings at various foundations. UPNE is one of three presses that recently received challenge grants from NEH for publishing in the humanities, and the Mellon Foundation also made a substantial award to the press for the acquisition of first book manuscripts from young humanists and for the development of new technologies in editing and production.

All this good news is crossing the waters as well. Since 1980, the title

page of UPNE books has carried a London as well as a Hanover address, the press having affiliated with the presses of California, Cornell, and Johns Hopkins in a joint international company based in London that markets for them all in the United Kingdom, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Through this affiliation, UPNE books have been displayed at book fairs all over Frankfurt, Warsaw, Jerusalem, Moscow, and Cairo. More recently, the press has employed an agent to represent its publications in Asia and the Pacific, and there are also plans for promotion in the People's Republic of China.

These eight universities clearly have a good thing going, and it is cause for wonder that no similar interstate enterprise has sprung up since UPNE's inception. The crossing of state lines is important, according to Home: "It's a significant difference, to encompass a broader geographical area than a state. There are more diverse points of view to be accommodated and that is reflected in a broader, more cosmopolitan publications list that is not so insular." The setting may be unique, surmises McFarland: "Perhaps we exist in a context that cannot be duplicated else where:a small, well-defined region which happens to contain the greatest concentration of educational institutions in the world, but which is short on university presses of the eighty some members of the AAUP, only six are in New England."

Is UPNE looking for new members? "Well," says McFarland, "we are not aggressively looking but we are genuinely interested in exploring new relationships with institutions in tune with our mission." Johnson feels that the press needs to get a little bigger, for a couple of reasons, among them the need for greater sales that would allow him to attract representatives for two areas of the country not now adequately represented the West Coast and the Deep South. Johnson would also like to be big enough to have plenty of offerings on the list to interest bookstores. "Bigger is not necessarily better," he admits, "but to realize certain financial efficiencies, we ought to grow a little more."

Size has been an important consideration at UPNE since the beginning. Its constitution mandates a ceiling of ten members, and every director of the consortium has treasured its smallness. "In this small operation, authors do not get lost," explains Home, who came to UPNE from the Harvard University Press. "I remember how over and over again at association meetings, authors would come to me almost in tears because they had been working with so-and-so at some big press and so-and-so had suddenly left and now that press was saying it wasn't going to publish the book after all, 'So sue us.' "

McFarland's big-press experience was gained as assistant director both at the Johns Hopkins University Press and at the University of California Press at Berkeley, and he has a similar concern for authors: "In this society that has sold itself to bigness, there are many authors who long for the days when editors and publishers talked about books and ideas rather than corporation profits, inventory tax rulings, and so forth. This university press consortium is working in part because we are small and we can deal individually with our authors and their needs."

Individually and successfully, as an eminent Oxford historian recently testified to with especial warmth. "The advance copy of my book arrived here two days ago," Richard Cobb wrote after UPNE's publication of his Frenchand Germans, Germans and French. "I am absolutely delighted with it, I love the jacket, and the whole thing is beautifully produced, first-class workmanship. It is my first book with a U.S. publisher, and the experience has been so entirely agreeable I am very tempted to renew it."

That's really what UPNE is all about, says McFarland "signing up important books and good authors."

The late Victor Reynolds '27 came out ofretirement to start up UPNE, donatinghis services as a Bicentennial gift to Dartmouth.

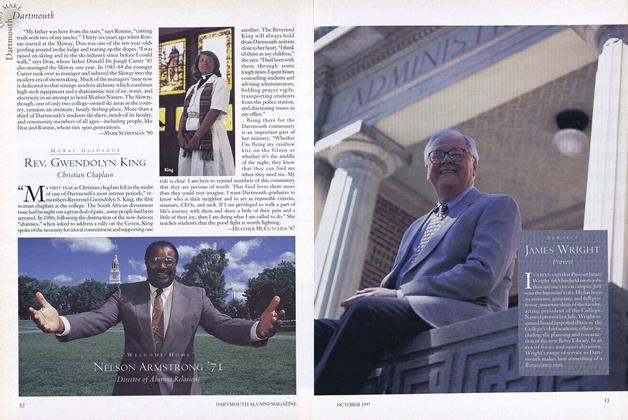

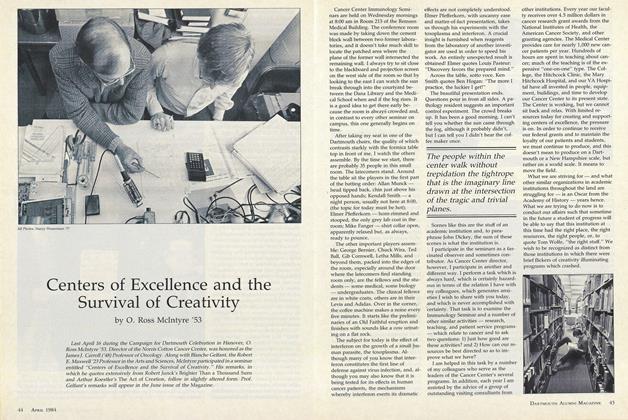

The staff at UPNE, flanked by its handiwork: left to right; Ruth Friend, secretary and project assistant; Aaron Richardson '85,student assistant; Charles Backus, acquisitions editor; Barbara Ras, managing editor; Thomas McFarland, director; ThomasJohnson, financial officer and sales manager; Amy Patterson, accounting clerk; Nanine Hutchinson, marketing manager, andSarah May Clarkson, editorial and marketing assistant. (Two members of the staff Anne Demers, shipping clerk, and PriscillaMoore, order-processing clerk are not in the photograph.)

"The excitementsays David Home,retired second director of UPNE,"comes from seeing a manuscript youbelieve in become a book you can hold inyour hand."

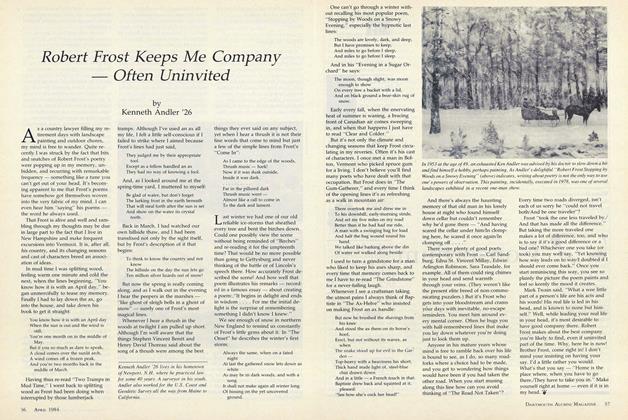

Portrait of success: from left to right, a pleased publisher (McFarland), a worthysubject (sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens), a prize-winning book (The Work of Augustus Saint-Gaudens;, and a happy author (John Dryfhout), photographed inthe studio of the artist's Cornish, New Hampshire, home, which is now a NationalHistoric Site.

There is a university press land that is publishing books in LANDECONOMICS you should know about. Water ResourcesPlanning in NewEngland, by Stuart G. Koch, $12.00 A PloughWestern Agribusinessin Third World Agriculture, by Sarah Potts Voll, $12.00 Water Re-Use andthe Cities, edited by Roger E. and Jeanne X. Kasperson, $17.50 Drought in Botswana, "one of the best and most useful recent reports ... on drought in the developing countries"—Science, paper, $15.00 Energy and the En-vironment: A StructuralAnalysis, edited by Anne P. Carter, $15.00 BR ANDEIS • CLARK • DARTMOUTH • NEW HAMPSHIRE -RHODE ISLAND • TUFTS-VERMONT University Press ofNew England Hanover, New Hampshire and London, England There is a university press in New England that is publishing books that bookstores love to sell "A Good Poor Man's Wife" Being A Chronicle of Harriet Hanson Robinson and Her Family in19th-century New England, by Claudia L. Bushman, $18.00 Gordon,'$17.50 Indian New England Before the Mayflower by Howard S. Russell, Amateur Sugar Maker by Noel Perrin, $7.50 Brandeis • Brown • Clark Dartmouth • New Hampshire Rhode Island • Tufts • Vermont University Press of New England Hanover and London These two award-winning ads were partof a series of 15 created in 1983 to run in The New York Review of Books.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHanover Sabbatical

April 1984 By Robert Conn '61 -

Feature

FeatureCenters of Excellence and the Survival of Creativity

April 1984 By O. Ross Mclntyre '53 -

Feature

FeatureRobert Frost Keeps Me Company Often Uninvited

April 1984 By Kenneth Andler '26 -

Article

ArticleIt's Just Like Talking to People

April 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1984 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1984 By Harry R. Zlokower

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureMen and Women: What's the Difference?

OCT. 1977 By Dan Nelson, Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe conquest of Kiewit (sort of)

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

MARCH 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Dinan Decade

OCTOBER, 1908 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham