By Andrew M. Scott '45 andMargaret A. Hunt. Chapel Hill, N. C.:The University of North Carolina Press,1966. 106 pp. $4.50.

In the summer of 1884, a 28-year-old graduate student at Baltimore's Johns Hopkins University completed his Ph.D. dissertation - to be published the next year as a book entitled Congressional Government. It was an attempt to describe realistically how the American political system worked at the time. As the title implies, the author's major thesis was that Congress was the central power in the American system.

Twenty-five years later, the same author (then president of a small college for young men in Princeton, N. J.) wrote another book, Constitutional Government in theUnited States, which was in many respects the antithesis of the first: the President, not the Congress, was at "the front of affairs." In this second work is the model of American national politics which the author, Woodrow Wilson, took with him to the White House in 1912.

Like Wilson's second volume, Andrew Scott and Margaret Hunt's slim but meaty Congress and Lobbies provides a necessary antithesis to one outdated (if ever accurate) thesis of American politics: in this case the muckraking, inside-dopesters' assumption that it is the paid lobbyists of Big Business, Organized Labor, and Subsidized Agriculture who pay the pipers and call the tunes in the American Congress. To the contrary, the two University of North Carolina political science professors find that the impact of lobbying by major organized interest groups on Congressmen has been greatly exaggerated. They maintain that the national legislative process is not dominated by lobbies.

But of greater interest to those who have had little recent contact with academic political scientists is the striking contrast between the methods of investigation reflected in Wilson's work (and in that of most political scientists prior to the mid-1950s) and in Scott and Hunt's study. Neil MacNeil, former Congressional correspondent for Time magazine, recently recalled our attention to the fact that Wilson wrote his first book on Congress without deigning to make the short journey from Johns Hopkins to Capitol Hill. Scott and Hunt, like an increasing number of students of our national legislature, have frequented the corridors and offices of Congress. The authors literally laid siege to a sample of Representatives to have them describe their contacts, their actions, and their own evaluations of the influence of lobbyists on their legislative decisions.

The authors discovered that virtually all Congressmen accept interest group activity as a normal part of the legislative process. The Members look upon lobbies as valuable sources of information and as representatives of the wants and needs of an increasingly pluralistic American society. They also found, however, that legislators are apt to be resentful if lobbyists encroach upon what Congressmen view as their exclusive domain - that is, law-making.

According to the authors, there are three major reasons why lobbies do not dominate the legislative process. The claims of organized interest groups are not the only demands made upon Members of Congress; the weapons of pressure at their disposal are of modest effectiveness at best, and the demands they make are not passively received by Congressmen but are channeled and modified by the formal rules and the informal "folkways" operating in Congress.

The assumptions, methods, and conclusions reflected in Congress and Lobbies may be faulted when evaluated against the canons of an increasingly rigorous methodology of political science and the findings of several more recent and ambitious studies. But for those afflicted with the old muckraking image of pressure politics this volume is recommended as a startlingly effective antidote.

Assistant Professor of Government

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMILITARY POWER: THE FADING PERSUADER

October 1966 By LIEUTENANT GENERAL JAMES M. GAVIN -

Feature

FeatureWORLD UNDERSTANDING: A Job for Mass Communications

October 1966 By WALTER WANGER '15 -

Feature

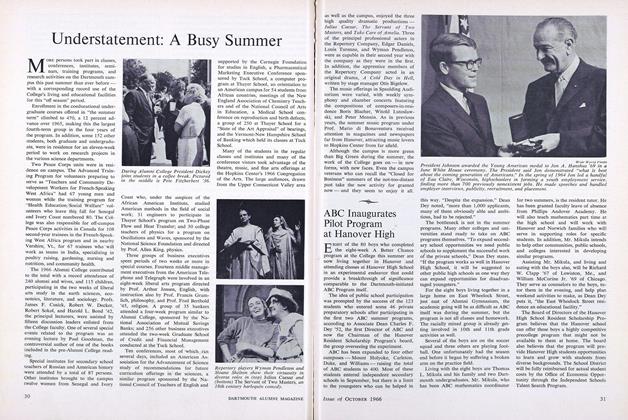

FeatureUnderstatement: A Busy Summer

October 1966 -

Feature

FeatureA Landmark Goes Down

October 1966 -

Feature

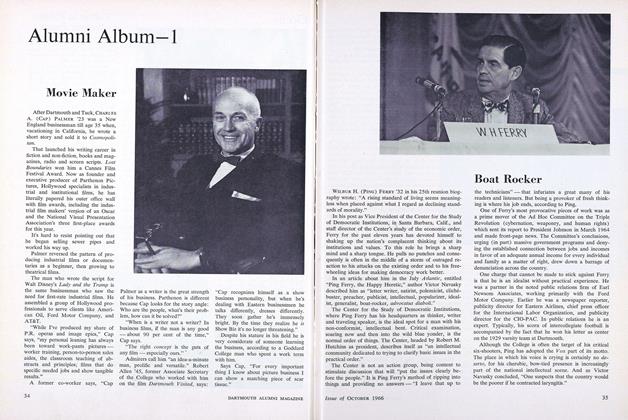

FeatureBoat Rocker

October 1966 -

Feature

FeaturePress Secretary

October 1966

Books

-

Books

BooksThe French Revolution and Napolean

November 1917 By A.H.B. -

Books

BooksBOSTON POSTAL MARKINGS TO

January 1950 By C. N. Allen '24 -

Books

BooksFURNITURE MARKETING.

MAY 1957 By CLYDE E. DANKERT -

Books

BooksA GUIDE TO TROLLOPE

October 1948 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

Books"SUNNY INTERVALS." A BOOKMAN'S MISCELLANEA: LONDON/SAN FRANCISCO/HANOVER.

FEBRUARY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksDANIEL WEBSTER

January, 1931 By Leon B. Richardson