Student Viewpoint 1966

VICE PRESIDENT OF THE DARTMOUTH CHRISTIAN UNION

CONSIDERING the complexity of the phenomenon of student activism at Dartmouth - or anywhere, for that matter — I should hardly welcome the opportunity to generalize about its nature in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. Hopefully, however, I can suggest some of the problems involved in its growth here in Hanover and can comment on the general direction activism seems to be taking.

W. H. Ferry '32 suggested in a recent issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE that Dartmouth is no more than "a bywater of glassy calm amidst the growing turbulence on American campuses. . . Alum- nus J. C. Forsythe '46, in fact, advises that the "green behind the ears group of undergraduate students, divinity school graduates, and professors without business world experience [should] keep their big mouths shut."

To begin, then, I would contend that those who feel that there is little activism at Dartmouth have every reason to consider their assertion correct. In this1 article I will deal specifically with five reasons why this is so, although there may be more.

First let us consider the administration of the College. What is there about this body that either encourages or discourages an active response to important social and political issues? There seems to be something discouraging about the fact that the President of the College has refrained from presenting his views on con- troversial issues to the student body. We know from his Convocation addresses that he has definite feelings about great issues, but should we be led to believe that his once-a-year appearance before the students is the only indication of his concern for our consideration of these issues? Surely the Dean of the Tucker Foundation does not speak for the entire administration on domestic and foreign issues, and yet apart from their speeches at football rallies we have no idea what our deans and their assistants think about the war in Vietnam. I am not calling for administration activists but I do think that in view of the imminence of student involvement in a war, they might consider the responsibility of working towards stimulating a healthy climate of concern.

Perhaps they feel that other more qualified persons should provide this sort of stimulation. Hence we may look to the Commencement speakers of the recent past and the near future as possible sources of inspiration. However, Messieurs Lesage, Udall, and Macy are not exactly renowned for taking stands on controversial subjects. We may all agree that conservation is beneficial but we don't all feel that way about the war in Vietnam.

I wonder if there is any significance in the fact that with the exception of U Thant in 1963 there have been no honorary degrees bestowed upon issue-oriented, social reformers in the past five years.

The Great Issues course offered to seniors might be a sincere attempt to remedy this problem and yet, among other difficulties, the policy of compulsory attendance seems so thoroughly to antagonize the "beneficiaries" that the possibility of a natural and interested response to a speaker is too often stifled and the overall goal is nullified.

But the administration is certainly not the only or the main reason why Dartmouth may not be conspicuous for its activism. With the exception of occasional speakers, student organizations are primarily responsible for the pervading passivity on campus. Student government openly objects to extending its role to any active participation in national and international student organizations. Withdrawal from the National Student Association, which is known for having initiated programs such as food distribution in impoverished communities and sponsoring conferences on social and political issues inside and outside the United States, perhaps most clearly represents the self-limiting goals of our student government.

This latter group is not always a passive force on campus. It actively discourages recognition of student organizations that are affiliated with national organizations. Last year, for example, the Young Americans for Freedom were deprived of their College support and thus forced to withdraw from the campus. This appears to be a clear example of how our student government consciously perpetrates the problem of provincial thinking here at Dartmouth.

Fraternities are another reason why an undergraduate might not seriously consider activism while at Dartmouth. Fraternities are not merely arenas of recreation for the socially minded student. They are inner-oriented organizations that exert an extraordinary degree of pressure on a student to direct his loyalty to his "brotherhood." Every student, whether he is a brother or an independent, should have the freedom to think and act first as a responsible individual in a world community and not first as a devotee of a "brotherhood." This is a freedom that the Dartmouth fraternity curtails in the individual. Freedom to think and act as an individual is an exceedingly high price to pay to any one institution and it has utifortunately cost the College the respon. sible thought and actions of too many men.

Our college newspaper may be the oldest and the poorest in the nation. Actually activism at Dartmouth is only one element that suffers from the misguided efforts of The D, but it is certainly one of its greatest victims. While editorial columns of effective college newspapers often provide and even stimulate a forum for exchange of ideas on foreign and domestic policy, our editorial columns have difficulty presenting an adequate coverage of campus issues. Ironically, even a cursory glance at The D would suggest that our athletic program is the most admirable part of the Dartmouth experience and I needn't comment on the implications of that misconception.

Fortunately the College radio is dedicated to covering "what's happening" anywhere and at any time, but its efforts hardly compensate for the shortcomings of the newspaper.

Tradition at Dartmouth also discourages activism on campus. Presently one of our great traditions is to not blow one's cool, which means not only don't get excited but don't act. This particular tradition is consciously or unconsciously cultivated in a freshman by his I.D.C. man who, during Freshman Week, clearly establishes just what it means to be a "screamer," and the activist, who more often than not is outspoken about his convictions, invariably acquires this dubious title.

IN spite of all these obstacles activism at Dartmouth is undeniably emerging as a small but significant force on campus. As I write this article, members, sympathizers and non-sympathizers of the Students for a Democratic Society are gathered for one of the seven seminars that have met this week to consider our policy in Vietnam. No one believes that these meetings are going to have an enormous impact on the opinions of the undergraduate body as a whole but there is something new and extremely refreshing about the idea that students and faculty from all positions in the political spectrum are exchanging ideas on this question. For some it is an opportunity to present or defend their views for the first time. Others are reinforced in or stripped of their convictions.

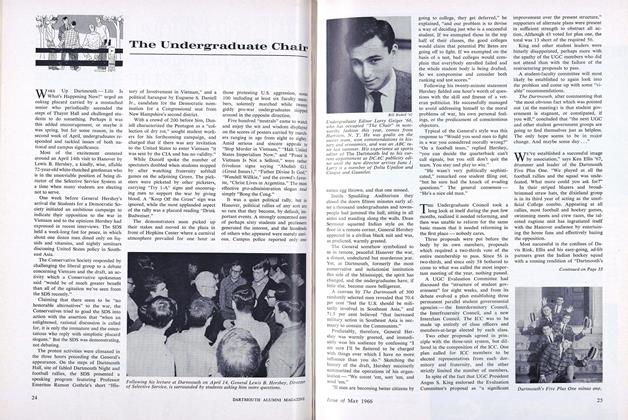

More controversial and no less important was the demonstration and rally that occurred in front of Hopkins Center prior to the address of the Selective Service Dimeter General Lewis Hershey. Approximately 120 students and faculty members visibly demonstrated their convictions about the war. Many, demonstrating for the first time, had given hours of thought to the meaning of demonstrating. Counter-demonstrators and hecklers were numerous, humorous but most of all cynical Sadly enough many of them never stopped to consider how and why these people were demonstrating. Criticized for slovenliness, most of the demonstrators were actually neat in appearance and presented their case responsibly. Accused of having Communist tendencies, many of them were concerned with the moral implications in our foreign policy.

Other occasions have been equally instrumental in stimulating thought on campus. Earlier this year there were two symposiums on Vietnam. David Dean of the State Department participated in a debate on Vietnam before some 500 people in Spaulding Auditorium. Senator Ernest Gruening of Alaska criticized the policy of military involvement in Vietnam before 700 students in the same auditorium, and six Dartmouth professors presented their views on the war during a four-hour session in the Top of the Hop.

The Conservative Society has become a more assertive body in recent times. They are consistently outspoken at symposiums and seminars on domestic and foreign policy and this year have twice published well-written, thought-provoking articles regarding national and international issues.

Students working in the Political Action Commission of the Dartmouth Christian Union have been a consistent political force working for the Civil Rights Movement. During the winter term they worked with faculty members and towns people to raise $3000 for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

The Tucker Foundation has recently inaugurated its Talladega program in which white and Negro students will work together in impoverished communities in the North and the South.

Last month the College hosted 400 people attending a conference entitled "Community Development and the University." Sponsored by the Comparative Studies Center, the Peace Corps, Student World Alliance for Progress, Cutter Hall, and the DCU Political Action Commission, this conference featured the foremost spokesmen in our country for community development, including Saul Alinsky of the Industrial Areas Foundation, James Forman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and Frank Mankiewicz of the Peace Corps.

In short, it seems just as accurate to say that activism is nonetheless growing in importance at Dartmouth as it is to observe that it is discouraged here. I for one am glad I am here at Dartmouth now when social and political action is beginning to emerge as a distinct possibility for a Dartmouth student.

Two years ago, David Weber '65, president of the Undergraduate Council, stood before the College at Convocation and told us that Dartmouth is in trouble because students have lost their capacity to tolerate and even express individuality on campus. When he finished we stood up and gave him a thunderous ovation then we all sat down and we've been sitting ever since. Most of us have anyway. Fortunately there are some who refuse to sit, and their voices will be heard in this wilderness.

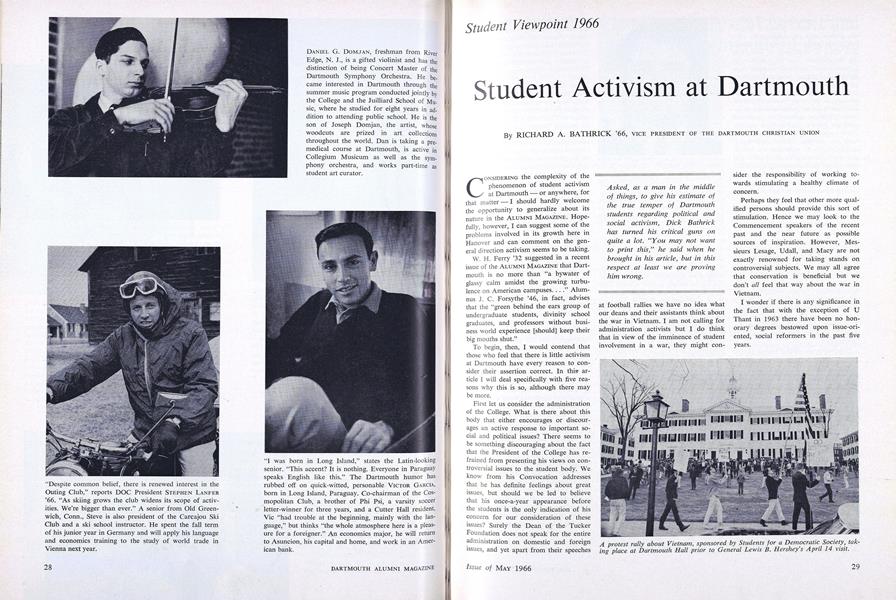

A protest rally about Vietnam, sponsored by Students for a Democratic Society, taking place at Dartmouth Hall prior to General Lewis B. Hershey's April 14 visit.

Author Dick Batlirick '66, whose homeis in Darien, Conn., has been active inthe Political Action Commission of theDCU, which he serves as vice president.He is captain of the Dartmouth RugbyClub, a sport his brother, Dave Bathrick'5B, also played in addition to being atackle on the football team. Dick, whoattended Ecole Lemania in Lausanne, isthe son of John N. Bathrick '34.

Marchers and counter-marchers on the plaza before Hopkins Center contributed tothe commotion on April 14, the biggest day of student activism Hanover has seen.

Asked, as a man in the middleof things, to give his estimate ofthe true temper of Dartmouthstudents regarding political andsocial activism, Dick Batlirickhas turned his critical guns onquite a lot. "You may not wantto print this," he said when hebrought in his article, but in thisrespect at least we are provinghim wrong.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

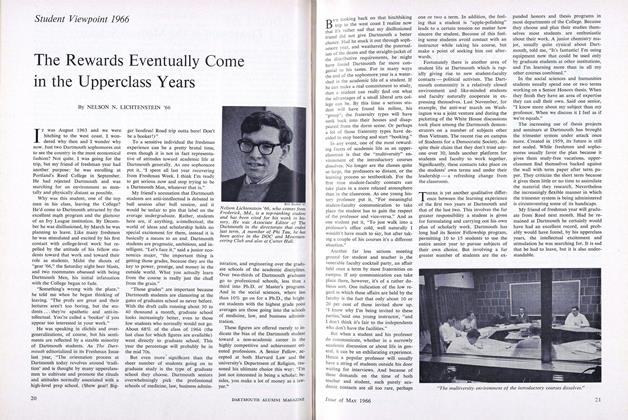

FeatureThe Rewards Eventually Come in the Upperclass Years

May 1966 By NELSON N. LICHTENSTEIN '66 -

Feature

FeatureANGLOPHILIA HITS THE CAMPUS

May 1966 By ARTHUR N. HAUPT '67 -

Feature

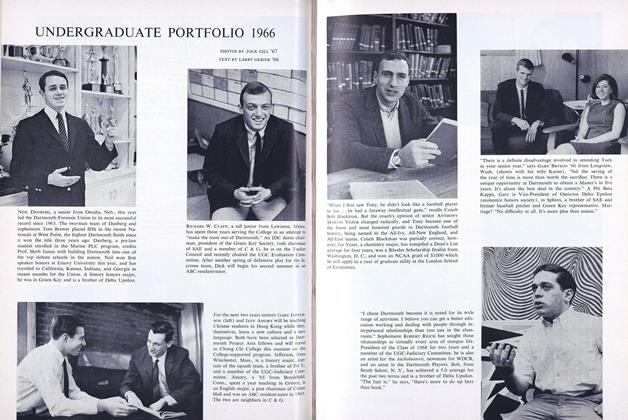

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE PORTFOLIO 1966

May 1966 By TEXT BY LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

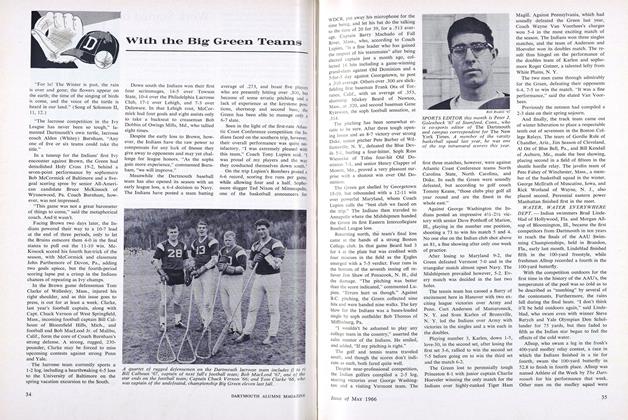

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

May 1966 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

May 1966 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT

Features

-

Feature

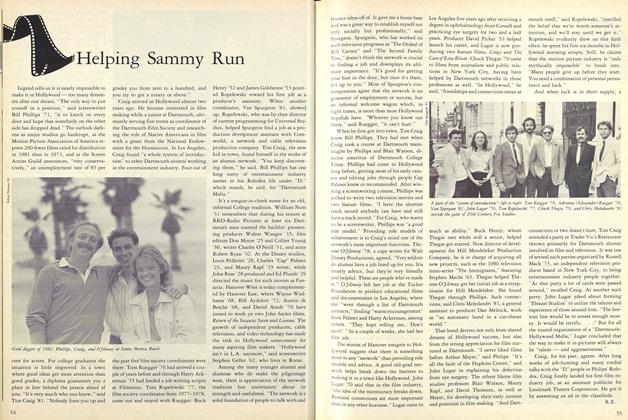

FeatureHelping Sammy Run

November 1982 -

Feature

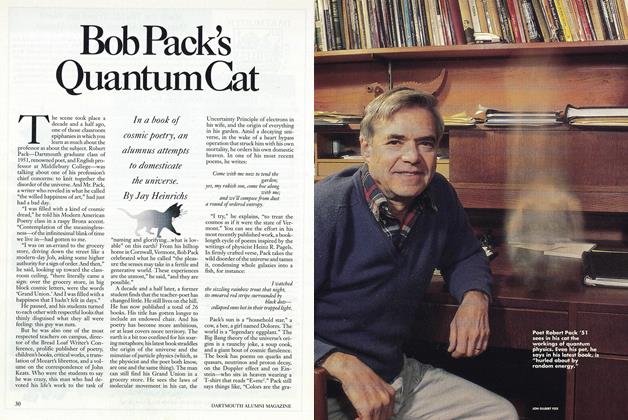

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2005 -

Feature

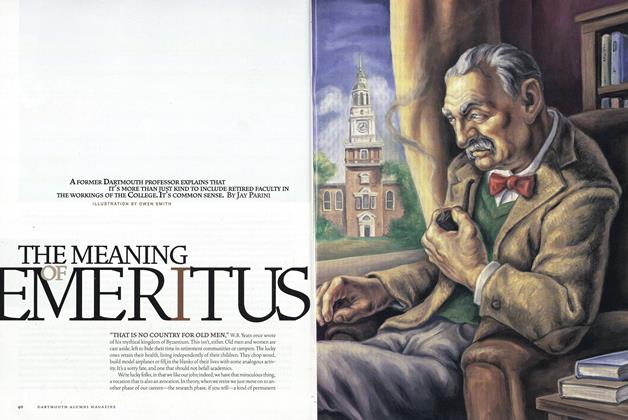

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

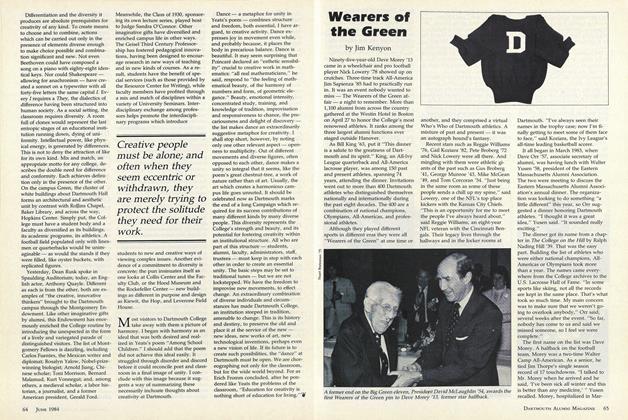

FeatureThe Meaning of Emeritus

July/August 2001 By Jay Parini -

Feature

FeatureWearers of the Green

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureHow the Dutch Handle It

JUNE 1973 By Robert D. Haslach '68