Student Viewpoint 1966

IT was August 1963 and we were hitching to the west coast. I wondered why then and I wonder why now. Just two Dartmouth sophomores out to see the country in the most economical fashion? Not quite. I was going for the trip, but my friend of freshman year had another purpose: he was enrolling at Portland's Reed College in September. He had rejected Dartmouth and was searching for an environment as mentally and physically distant as possible.

Why was this student, one of the top men in his class, leaving the College? He'd come to Dartmouth attracted by the excellent math program and the glamour of an Ivy League institution. By December he was disillusioned, by March he was planning to leave. Like many freshmen he was stimulated and excited by his first contact with college-level work but repelled by the attitude of his fellow students toward that work and toward their role as students. Midst the shouts of "gear '66," the Saturday night beer blasts, and two roommates obsessed with being Dartmouth Men, his initial infatuation with the College began to fade.

"Something's wrong with the place," he told me when he began thinking of leaving. "The profs are great and their lectures aren't too boring, but the students ... they're apathetic and anti-intellectual. You're called a 'booker' if you appear too interested in your work."

He was speaking in cliches and over generalizations, of course, but his sentiments are reflected by a sizable minority of Dartmouth students. As The Dartmouth editorialized in its Freshman Issue last year, "The orientation process at Dartmouth today revolves around 'tradition' and is thought by many upperclassmen to cultivate and promote the rituals and attitudes normally associated with a high-level prep school. (Show gear! Bigger bonfires! Road trip outta here! Don't be a booker!)"

To a sensitive individual the freshman experience can be a pretty brutal time, even though it is not in fact representative of attitudes toward academic life at Dartmouth generally. As one sophomore put it, "I spent all last year recovering from Freshman Week. I think I'm ready to get serious now and stop trying to be a Dartmouth Man, whatever that is."

My friend's accusation that Dartmouth students are anti-intellectual is debated in bull session after bull session, and it would be unfair to pin that label on the average undergraduate. Rather, students here are, if anything, a-intellectual; the world of ideas and scholarship holds no special excitement for them, instead it is basically a means to an end. Dartmouth students are pragmatic, ambitious, and intelligent. "Let's face it," said a junior economics major, "the important thing is getting those grades, because they are the key to power, prestige, and money in the outside world. What you actually learn from the course is really just the chaff from the grain."

"Those grades" are important because Dartmouth students are clamoring at the gates of graduates school as never before. With the draft calls running about 30 to 40 thousand a month, graduate school looks increasingly better, even to those few students who normally would not go. About 68% of the class of 1964 (the last class for which figures are available) went directly to graduate school. This year the percentage will probably be in the mid 70s.

But even more significant than the sheer number of students going on to graduate study is the type of graduate school they choose. Dartmouth seniors overwhelmingly pick the professional schools of medicine, law, business administration, and engineering over the graduate schools of the academic disciplines. Over two-thirds of Dartmouth graduates go to professional schools, less than a third into Ph.D. or Master's programs. And in the social sciences, where less than 10% go on for a Ph.D., the brightest students with the highest grade point averages are those going into the schools of medicine, law, and business administration.

These figures are offered merely to indicate the bias of the Dartmouth student toward a non-academic career in the highly competitive and achievement oriented professions. A Senior Fellow, accepted at both Harvard Law and the university's Department of Religion, reasoned his ultimate choice this way: "I'm just not interested in being a scholar; besides, you make a lot of money as a lawyer."

BUT looking back on that hitchhiking trip to the west coast I realize now that it's rather sad that my disillusioned friend did not give Dartmouth a better chance. Had he stuck it out through sophomore year, and weathered the paternalism of the deans and the straight-jacket of the distributive requirements, he might have found Dartmouth far more congenial to his tastes. For in many ways The end of the sophomore year is a watershed in the academic life of a student. If he can make a real commitment to study, then a student can really find out what the advantages of a small liberal arts college can be. By this time a serious student will have found his milieu, his "group"; the fraternity types will have sunk back into their houses and disappeared from the dorm scene. Or perhaps a lot of those fraternity types have decided to stop beering and start "booking."

In any event, one of the most rewarding facets of academic life as- an upperclassman is that the "multiversity" environment of the introductory courses dissolves. No longer are the classes quite so large, the professors so distant, or the learning process so textbookish. For the first time student-faculty contacts can take place in a more relaxed atmosphere than in the classroom. As one young history professor put it, "For meaningful student-faculty communication to take place the student has to gain the respect of the professor and vice-versa." And as one student put it, "To just walk into a professor's office cold, well naturally I wouldn't have much to say, but after taking a couple of his courses it's a different situation."

Another far less serious meeting ground for student and teacher is the venerable faculty cocktail party, an affair held once a term by most fraternities on campus. If any communication can take place there, however, it's of a rather dubious sort. One indication of the low regard in which these affairs are held by the faculty is the fact that only about 10 or 20 per cent of those invited show up. "I know why I'm being invited to these parties, "said one young instructor, "and I don't think it's fair to the independents who don't have the facilities."

But when a student and his professor do communicate, whether in a narrowly academic discussion or about life in general, it can be an exhilarating experience. Hence a popular professor will usually have a string of students outside his door waiting for interviews. And because of these demands on the time of both teacher and student, such purely academic contacts are all too rare, perhaps one or two a term. In addition, the feeling that a student is "apple-polishing" leads to a certain tension no matter how sincere the student. Because of this feeling some students avoid contact with an instructor while taking his course, but make a point of seeking him out afterwards.

Fortunately there is another area of student life at Dartmouth which is rapidly giving rise to new student-faculty contacts - political activism. The Dartmouth community is a relatively closed environment and like-minded students and faculty naturally cooperate in expressing themselves. Last November, for example, the anti-war march on Washington was a joint venture and during the picketing of the White House discussions took place among the Dartmouth demonstrators on a number of subjects other than Vietnam. The recent rise on campus of Students for a Democratic Society, despite their claim that they don't trust any- one over 30, lends another platform for students and faculty to work together. Significantly, these contacts take place on the students' own terms and under their leadership - a refreshing change from the classroom.

THERE is yet another qualitative difference between the learning experience of the first two years at Dartmouth and that of the last two. This involves the far greater responsibility a student is given for formulating and carrying out his own plan of scholarly work. Dartmouth has long had its Senior Fellowship program, permitting 10 to 15 students to use the entire senior year to pursue subjects of their own choice. But involving a far greater number of students are the expanded honors and thesis programs in most departments of the College. Because they choose and plan their studies them- selves most students are enthusiastic about their work. A junior chemistry ma- jor, usually quite cynical about Dart- mouth, told me, "It's fantastic! I'm using equipment now that could be used only by graduate students at other institutions, and I'm learning more than in all my other courses combined."

In the social sciences and humanities students usually spend one or two terms working on a Senior Honors thesis. When they finish they have an area of expertise they can call their own. Said one senior, "I know more about my subject than my professor. When we discuss it I feel as if we're equals."

The increasing use of thesis projects and seminars at Dartmouth has brought the trimester system under attack once more. Created in 1959, its future is still not sealed. While freshmen and sophomores usually favor the plan because it gives them study-free vacations, upperclassmen find themselves backed against the wall with term paper after term paper. They criticize the short term because it gives them little or no time to assimilate the material they research. Nevertheless the increasingly flexible manner in which the trimester system is being administered is circumventing some of its handicaps.

My friend of freshman year will graduate from Reed next month. Had he remained at Dartmouth he certainly would have had an excellent record, and probably would have found, by his upperclass years, the intellectual excitement and stimulation he was searching for. It is sad that he had to leave, but it is also understandable.

Nelson Lichtenstein '66, who comes fromFrederick, Md., is a top-ranking studentand has been cited for his work in history. He was Associate Editor of The Dartmouth in the directorate that endedlast term. A member of Phi Tau, he hasbeen active in the DOC and Mountaineering Club and also at Cutter Hall.

"The multiversity environment of the introductory courses dissolves."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStudent Activism at Dartmouth

May 1966 By RICHARD A. BATHRICK '66 -

Feature

FeatureANGLOPHILIA HITS THE CAMPUS

May 1966 By ARTHUR N. HAUPT '67 -

Feature

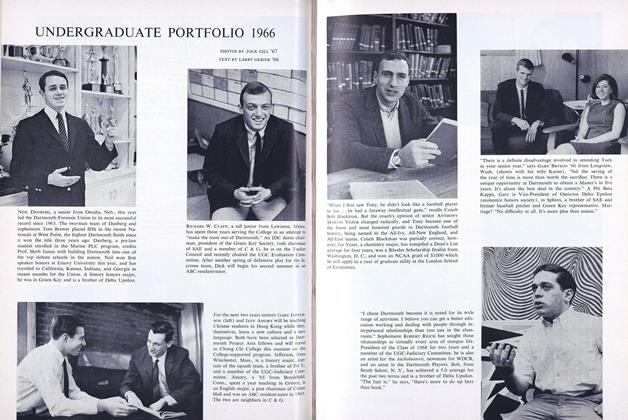

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE PORTFOLIO 1966

May 1966 By TEXT BY LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

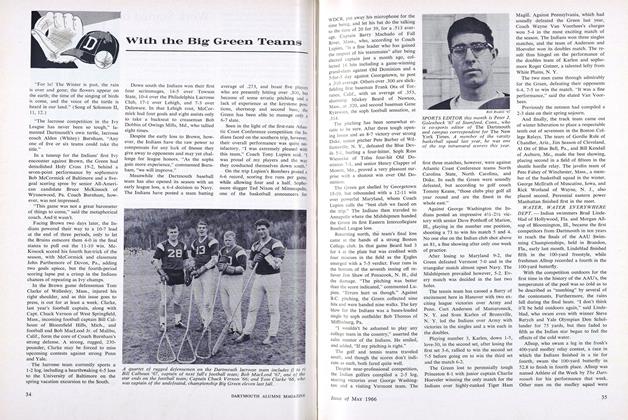

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

May 1966 -

Article

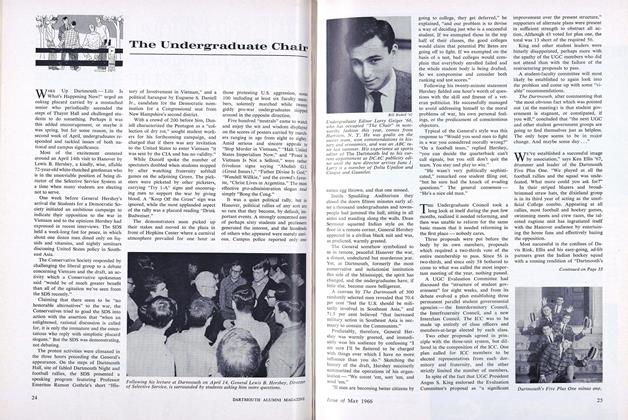

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

May 1966 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT

Features

-

Feature

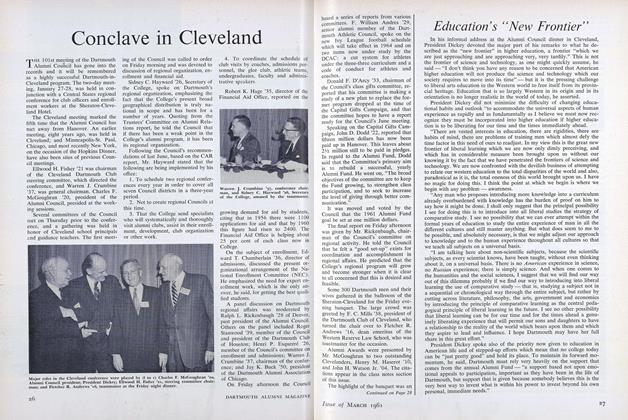

FeatureEducation's "New Frontier"

March 1961 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCOMMENCEMENT

June • 1985 -

Feature

FeatureSome Views About Dartmouth Athletics From the Man Who Directs the Program

DECEMBER 1971 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Very Old and the Old

February 1962 By DR. FREDERIC P. LORD '98 -

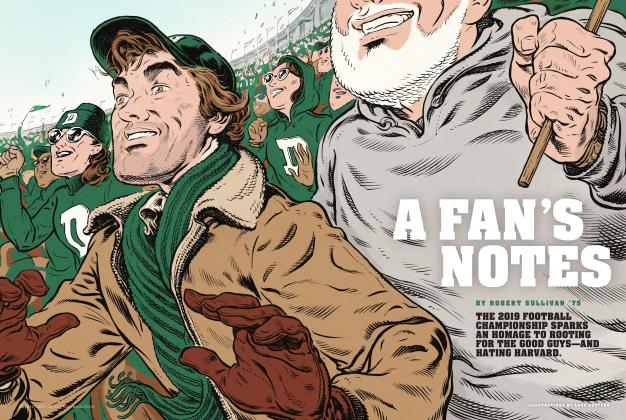

FEATURE

FEATUREA Fan’s Notes

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Cover Story

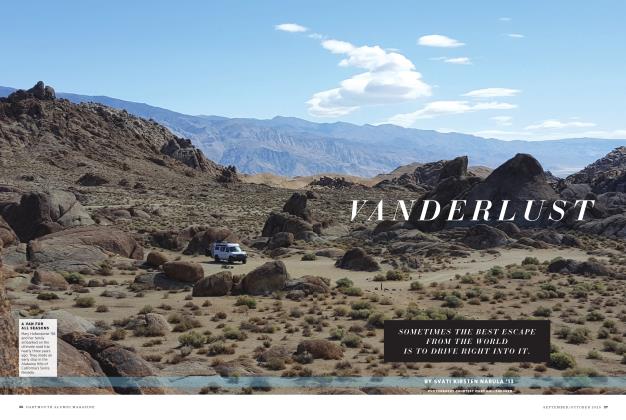

Cover StoryVanderlust

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2020 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13