Americans colleges and universities,recipients of billions in Federal funds,have a new relationship:

WHAT WOULD HAPPEN if all the Federal dollars now going to America's colleges and universities were suddenly withdrawn?

The president of one university pondered the question briefly, then replied: "Well, first, there would be this very loud sucking sound."

Indeed there would. It would be heard from Berkeley's gates to Harvard's yard, from Colby, Maine, to Kilgore, Texas. And in its wake would come shock waves that would rock the entire establishment of American higher education.

No institution of higher learning, regardless of its size or remoteness from Washington, can escape the impact of the Federal government's-involvement in higher education. Of the 2,200 institutions of higher learning,in the United States, about 1,800 participate in one or more Federally supported or sponsored programs. (Even an institution which receives no Federal dollars is affected—for it must compete for faculty, students, and private dollars with the institutions that do receive Federal funds for such things.)

Hence, although hardly anyone seriously believes that Federal spending on the campus is going to stop or even decrease significantly, the possibility, however remote, is enough to send shivers down the nation's academic backbone. Colleges and universities operate on such tight budgets that even a relatively slight ebb in the flow of Federal funds could be serious. The fiscal belt-tightening in Washington, caused by the war in Vietnam and the threat of inflation, has already brought a financial squeeze to some institutions.

A look at what would happen if all Federal dollarswere suddenly withdrawn from colleges ahd universities may be an exercise in the absurd, but it dramatizes the depth of government involvement:

The nation's undergraduates would lose more than 800,000 scholarships, loans, and work-study grants, amounting to well over $300 million.

Colleges and universities would lose some $2 billion which now supports research on the campuses. Consequently some 50 per cent of America's science faculty members would be without support for their research. They would lose the summer salaries which they have come to depend on—and, in some cases, they would lose part of their salaries for the other nine months, as well.

The big government-owned research laboratories which several universities operate under contract would be closed. Although this might end some management headaches for the universities, it would also deprive thousands of scientists and engineers of employment and the institutions of several million dollars in overhead reimbursements and fees.

The newly established National Foundation for the Arts and Humanities—for which faculties have waited for years—would collapse before its first grants were spent.

Planned or partially constructed college and university buildings, costing roughly $2.5 billion, would be delayed or abandoned altogether.

Many of our most eminent universities and medical schools would find their annual budgets sharply reduced—in some cases by more than 50 per cent. And the 68 land-grant institutions would lose Federal institutional support which they have been receiving since the nineteenth century.

Major parts of the anti-poverty program, the new GI Bill, the Peace Corps, and the many other programs which call for spending on the campuses would founder.

A partnership of brains, money, and mutual need

THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT is HOW the "Big Spender" in the academic world. Last year, Washington spent more money on the nation's campuses than did the 50 state governments combined. The National Institutes of Health alone spent more on educational and research projects than any one state allocated for higher education. The National Science Foundation, also a Federal agency, awarded more funds to colleges and Universities than did all the business corporations in America. And the U.S. Office of Education's annual expenditure in higher education of $1.2 billion far exceeded all gifts from private foundations and alumni. The $5 billion or so that the Federal government will spend on campuses this year constitutes more than 25 per cent of higher education's total budget.

About half of the Federal funds now going to academic institutions support research and research-related activities—and, in most cases, the research is in the sciences. Most often an individual scholar, with his institution's blessing, applies directly to a Federal agency for funds to support his work. A professor of chemistry, for example, might apply to the National Science Foundation for funds to pay for salaries (part of his own, his collaborators', and his research technicians'), equipment, graduate-student stipends, travel, and anything else he could justify as essential to his work. A panel of his scholarly peers from colleges and universities, assembled by NSF, meets periodically in Washington to evaluate his and other applications. If the panel members approve, the professor usually receives his grant and his college or university receives a percentage of the total amount to meet its overhead costs. (Under several Federal programs, the institution itself can request funds to help construct buildings and grants to strengthen or initiate research programs.)

The other half of the Federal government's expenditure in higher education is for student aid, for books and equipment, for classroom buildings, laboratories, and dormitories, for overseas projects, and —recently, in modest amounts—for the general strengthening of the institution.

There is almost no Federal agency which does not provide some funds for higher education. And there are few activities on a campus that are not eligible for some kind of government aid.

CLEARLY our colleges and universities now depend so heavily on Federal funds to help pay for salaries, tuition, research, construction, and operatING costs that any significant decline in Federal support would disrupt the whole enterprise of American higher education.

To some educators, this dependence is a threat to the integrity and independence of the colleges and universities. "It is unnerving to know that our system of higher education is highly vulnerable to the whims and fickleness of politics," says a man who has held high positions both in government and on the campus.

Others minimize the hazards. Public institutions, they point out, have always been vulnerable in this sense—yet look how they've flourished. Congressmen, in fact, have been conscientious in their approach to Federal support of higher education; the problem is that standards other than those of the universities and colleges could become the determining factors in the nature and direction of Federal support. In any case, the argument runs, all academic institutions depend on the good will of others to provide the support that insures freedom. Mc George Bundy, before he left the White House to head the Ford Foundation, said flatly: "American higher education is more and not less free and strong because of Federal funds." Such funds, he argued, actually have enhanced freedom by enlarging the opportunity of institutions to act; they are no more tainted than are dollars from other sources; and the way in which they are allocated is closer to academic tradition than is the case with nearly all other major sources of funds.

The issue of Federal control notwithstanding, Federal support of higher education is taking its place alongside military budgets and farm subsidies as one of the government's essential activities. All evidence indicates that such is the public's will. Education has always had a special worth in this country, and each new generation sets the valuation higher. In a recent,Gallup Poll on national goals, Americans listed education as having first priority. Governors, state legislators, and Congressmen, ever sensitive to voter attitudes, are finding that the improvement of education is not only a noble issue on which to stand, but a winning one.

The increased Federal interest and support reflect another fact: the government now relies as heavily on the colleges and universities as the institutions do on the government. President Johnson told an audience at Princeton last year that in "almost every field of concern, from economics to national security, the academic community has become a central instrument of public policy in the United States."

Logan Wilson, president of the American Council on Education (an organization which often speaks in behalf of higher education), agrees. "Our history attests to the vital role which colleges and universities have played in assuring the nation's security and progress, and our present circumstances magnify rather than diminish the role," he says. "Since the final responsibility for our collective security and welfare can reside only in the Federal government, a close partnership between government and higher education is essential."

THE PARTNERSHIP indeed exists. As a report of the American Society of Biological Chemists has said, "the condition of mutual dependence between the Federal government and institutions of higher learning and research is one of the most profound and significant developments of our time."

Directly and indirectly, the partnership has produced enormous benefits. It has played a central role in this country's progress in science and technologg-and hence has contributed to our national security, our high standard of living, the lengthening life span, our world leadership. One analysis credits to education 40 per cent of the nation's growth in economic productivity in recent years.

Despite such benefits, some thoughtful observers are concerned about the future development of the government-campus partnership. They are asking how the flood of Federal funds will alter the traditional missions of higher education, the time-honored responsibility of the states, and the flow of private funds to the campuses. They wonder if the give and take between equal partners can continue, when one has the money and the other "only the brains."

Problems already have arisen from the dynamic and complex relationship between Washington and the academic world. How serious and complex such problems can become is illustrated by the current controversy over the concentration of Federal research funds on relatively few campuses and in certain sections of the country.

The problem grew out of World War 11, when the government turned to the campuses for desperately needed scientific research. Since many of the best-known and most productive scientists were working in a dozen or so institutions in the Northeast and a few in the Midwest and California, more than half of the Federal research funds were spent there. (Most of the remaining money went to another 50 universities with research and graduate training.)

The wartime emergency obviously justified this concentration of funds. When the war ended, however, the lopsided distribution of Federal research funds did not. In fact, it has continued right up to the present, with 29 institutions receiving more than 50 per cent of Federal research dollars.

To the institutions on the receiving end, the situation seems natural and proper. They are, after all, the strongest and most productive research centers in the nation. The government, they argue, has an obligation to spend the public's money where it will yield the highest return to the nation.

The less-favored institutions recognize this obligation, too. But they maintain that it is equally important to the nation to develop new institutions of high quality—yet, without financial help from Washington, the second- and third-rank institutions will remain just that.

In late 1965 President Johnson, in a memorandum to the heads of Federal departments and agencies, acknowledged the importance of maintaining scientific excellence in the institutions where it now exists. But, he emphasized, Federal research funds should also be used to strengthen and develop new centers of excellence. Last year this "spread the wealth" movement gained momentum, as a number of agencies stepped up their efforts to broaden the distribution of research money. The Department of Defense, for example, one of the bigger purchasers of research, designated SI 8 million for this academic year to help about 50 widely scattered institutions develop into high-grade research centers. But with economies induced by the war in Vietnam, it is doubtful whether enough money will be available in the near future to end the controversy.

Eventually, Congress may have to act. In so doing, it is almost certain to displease, and perhaps hurt, some institutions. To the pessimist, the situation is a sign of troubled times ahead. To the op- timist, it is the democratic process at work.

The haves and have-notcompete for limited funds

RECENT STUDENT DEMONSTRATIONS have dramatized another problem to which the partnership between the government and the campus has contributed: the relative emphasis that is placed on research and on the teaching of undergraduates.

Wisconsin's Representative Henry Reuss conducted a Congressional study of the situation. Subsequently he said: "University teaching has become a sort of poor relation to research. I don't quarrel with the goal of excellence in science, but it is pursued at the expense of another important goal—excellence of teaching. Teaching suffers and is going to suffer more."

The problem is not limited to universities. It is having a pronounced effect on the smaller liberal arts colleges, the women's colleges, and the junior colleges—all of which have as their primary function the teaching of undergraduates. To offer a first- rate education, the colleges must attract and retain a first-rate faculty, which in turn attracts good students and financial support. But undergraduate colleges can rarely compete with Federally supported universities in faculty salaries, fellowship awards, research opportunities, and plant and equipment. The president of one of the best undergraduate colleges says: "When we do get a young scholar who skill- fully combines research and teaching abilities, the universities lure him from us with the promise of a high salary, light teaching duties, frequent leaves, and almost anything else he may want."

Leland Haworth, whose National Science Foundation distributes more than $3OO million annually for research activities and graduate programs on the campuses, disagrees. "I hold little or no brief," he says, "for the allegation that Federal support of research has detracted seriously from undergraduate teaching. I dispute the contention heard in some quarters that certain of our major universities have become giant research factories concentrating on Federally sponsored research projects to the detriment of their educational functions." Most university scholars would probably support Mr. Haworth's contention that teachers who conduct research are generally better teachers, and that the research enterprise has infused science education with new substance and vitality.

To get perspective on the problem, compare university research today with what it was before World War 11. A prominent physicist calls the prewar days "a horse-and-buggy period." In 1930, colleges and universities spent less than $2O million on scientific research, and that came largely from private foundations, corporations, and endowment income. Scholars often built their equipment from ingeniously adapted scraps and spare machine parts. Graduate students considered it compensation enough just to be allowed to participate^

Some three decades and $125 billion later, there is hardly an academic scientist who does not feel pressure to get governnient funds. The chairman of one leading biology department admits that "if a young scholar doesn't have a grant when he comes here, he had better get one within a year or so or he's out; we have no funds to support his research."

Considering the large amounts of money available for research and graduate training, and recognizing that the publication of research findings is still the primary criterion for academic promotion, it is not surprising that the faculties of most universities spend a substantial part of their energies in those activities.

Federal agencies are looking for ways to ease the problem. The National Science Foundation, for example, has set up a new program which will make grants to undergraduate colleges for the improvement of science instruction.

More help will surely be forthcoming.

THL HE FACT that Federal funds have been concentrated in the sciences has also had a pronounced effect on colleges and universities. In many institutions, faculty members in the natural sciences earn more than faculty members in the humanities and social sciences; they have better facilities, more frequent leaves, and generally more influence on the campus.

The government's support of science can also disrupt the academic balance and internal priorities of a college or university. One president explained:

"Our highest-priority construction project was a $3 million building for our humanities departments. Under the Higher Education Facilities Act, we could expect to get a third of this from the Federal government. This would leave $2 million for us to get from private sources.

"But then, under a new government program, the biology and psychology faculty decided to apply to the National Institutes of Health for $1.5 million for new faculty members over a period of five years. These additional faculty people, however, made it necessary for us to go ahead immediately with our plans for a $4 million science building—so we gave it the No. 1 priority and moved the humanities building down the list.

"We could finance half the science building's cost with Federal funds. In addition, the scientists pointed but, they could get several training grants which would provide stipends to graduate students and tuition to our institution.

"You see what this meant? Both needs were valid —those of the humanities and those of the sciences. For $2 million of private money, I could either build a $3 million humanities building or I could build as 4 million science building, get 51.5 million for additional faculty, and pick up a few hundred thousand dollars in training grants. Either-or; not both."

The president could have added that if the scientists had been denied the privilege of applying to NIH, they might well have gone to another institu- tion, taking their research grants with them. On the other hand, under the conditions of the academic marketplace, it was unlikely that the humanities scholars would be able to exercise a similar mobility.

The case also illustrates why academic administrators sometimes complain that Federal support of an individual faculty member's research projects casts their institution in the ineffectual role of a legal middleman, prompting the faculty member to feel a greater loyalty to a Federal agency than to the college or university.

Congress has moved to lessen the disparity between support of the humanities and social sciences on the one hand and support of the physical and biological sciences on the other. It established the National Foundation for the Arts and Humanities- a move which, despite a pitifully small first-year allocation of funds, offers some encouragement. And close observers of the Washington scene predict that the social sciences, which have been receiving some Federal support, are destined to get considerably more in the next few years.

The affluence of researcha siren song to teachers

EFFORTS TO COPE with such difficult problems must begin with an understanding of the nature and background of the government-campus partnership. But this presents a problem in itself, for one encounters a welter of conflicting statistics, contradictory information, and wide differences of honest opinion. The task is further complicated by the swiftness with which the situation continually changes. And—the ultimate complication—there is almost no uniformity or coordination in the Federal government's numerous programs affecting higher education.

Each of the 50 or so agencies dispensing Federal funds to the colleges and universities is responsible for its own program, and no single Federal agency supervises the entire enterprise. (The creation of the Office of Science and Technology in 1962 represented an attempt to cope with the multiplicity of relationships. But so far there has been little significant improvement.) Even within the two houses of Congress, responsibility for the government's expenditures on the campuses is scattered among several committees.

Not only does the lack of a coordinated Federal program make it difficult to find a clear definition of the government's role in higher education, but it also creates a number of problems both in Washington and on the campuses.

The Bureau of the Budget, for example, has had to wrestle with several uncoordinated, duplicative Federal science budgets and with different accounting systems. Congress, faced with the almost impossible task of keeping informed about the esoteric world of science in order to legislate intelligently, finds it difficult to control and direct the fast-growing Federal investment in higher education. And the individual government agencies are forced to make policy decisions and to respond to political and other pressures without adequate or consistent guidelines from above.

The colleges and universities, on the other hand, must negotiate the maze of Federal bureaus with consummate skill if they are to get their share of the Federal largesse. If they succeed, they must then cope with mountains of paperwork, disparate systems of accounting, and volumes of regulations that differ from agency to agency. Considering the magnitude of the financial rewards at stake, the institutions have had no choice but to enlarge their administrative staffs accordingly, adding people who can handle the business problems, wrestle with paperwork, manage grants and contracts, and untangle legal snarls. College and university presidents are constantly looking for competent academic administrators to prowl the Federal agencies in search of programs and opportunities in which their institutions can profitably participate.

The latter group of people, whom the press calls "university lobbyists," has been growing in number. At least a dozen institutions now - have full-time representatives working in Washington. Many more have members of their administrative and academic staffs shuttling to and from the capital to negotiate Federal grants and contracts, cultivate agency personnel, and try to influence legislation. Still other institutions have enlisted the aid of qualified alumni or trustees who happen to live in Washington.

THE LACK of a uniform Federal policy prevents the clear statement of national goals that might give direction to the government's investments in higher education. This takes a toll in effectiveness and consistency and tends to produce contradictions and conflicts. The teaching-versus-research controversy is one example.

Fund-raisers prowl the Washington maze

President Johnson provided another. Last summer, he publicly asked if the country is really getting its money's worth from its support of scientific research. He implied that the time may have come to apply more widely, for the benefit of the nation, the knowledge that Federally sponsored medical research had produced in recent years. A wave of apprehension spread through the medical schools when the President's remarks were reported. The inference to be drawn was that the Federal funds supporting the elaborate research effort, built at the urging of the government, might now be diverted to actual medical care and treatment. Later the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, John W. Gardner, tried to lay a calming hand on the medical scientists' fevered brows by making a strong reaffirmation of the National Institutes of Health's commitment to basic research. But the apprehensiveness remains.

Other events suggest that the 25-year honeymoon of science and the government may be ending. Connecticut's Congressman Emilio Q. Daddario, a man who is not intimidated by the mystique of modern science, has stepped up his campaign to have a greater part of the National Science Foundation budget spent on applied research. And, despite pleas from scientists and NSF administrators, Congress terminated the costly Mohole project, which was designed to gain more fundamental information about the internal structure of the earth.

Some observers feel that because it permits and often causes such conflicts, the diversity in the government's support of higher education is a basic flaw in the partnership. Others, however, believe this diversity, despite its disadvantages, guarantees a margin of independence to colleges and universities that would be jeopardized in a monolithic "super-bureau."

Good or bad, the diversity was probably essential to the development of the partnership between Washington and the academic world. Charles Kidd, executive secretary of the Federal Council for Science and Technology, puts it bluntly when he points out that the system's pluralism has allowed us to avoid dealing "directly with the ideological problem of what the total relationship of the government and universities should be. If we had had to face these ideological and political pressures head-on over the past few years, the confrontation probably would have wrecked the system."

That confrontation may be coming closer, as Federal allocations to science and education come under sharper scrutiny in Congress and as the partnership enters a new and significant phase.

FEDERAL AID to higher education began with the Ordinance of 1787, which set aside public lands for schools and declared that the "means of education shall forever be encouraged." But the two forces that most shaped American higher education, say many historians, were the land-grant movement of the nineteenth century and the Federal support of scientific research that began in World War II.

The land-grant legislation and related acts of Congress in subsequent years established the American concept of enlisting the resources of higher education to meet pressing national needs. The laws were pragmatic and were designed to improve education and research in the natural sciences, from which agricultural and industrial expansion could proceed. From these laws has evolved the world's greatest system of public higher education.

In this century the Federal involvement grew spasmodically during such periods of crisis as World War I and the depression of the thirties. But it was not until World War II that the relationship began its rapid evolution into the dynamic and intimate partnership that now exists.

Federal agencies and industrial laboratories were ill-prepared in 1940 to supply the research and technology so essential to a full-scale war effort. The government therefore turned to the nation's colleges and universities. Federal funds supported scientific research on the campuses and built huge research facilities to be operated by universities under contract, such as Chicago's Argonne Laboratory and California's laboratory in Los Alamos.

So successful was the new relationship that it continued to flourish after the war. Federal research search funds poured onto the campuses from military agencies, the National Institutes of Health, the Atomic Energy Commission, and the National Science Foundation. The amounts of money increased spectacularly. At the beginning of the war the Federal government spent less than $200 million a year for all research and development. By 1950, the Federal "r & d" expenditure totaled $1 billion.

The Soviet Union's launching of Sputnik jolted the nation and brought a dramatic surge in support of scientific research. President Eisenhower named James R. Killian, Jr., president of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to be Special Assistant to the President for Science and Technology. The National

Aeronautics and Space Administration was established, and the National Defense Education Act ol 1958 was passed. Federal spending for scientific research and development increased to $5.8 billion Of this, 1400 million went to colleges and universities.

The 1960's brought a new dimension to the relationship between the Federal government and highei education. Until then, Federal aid was almost syr onymous with government support of science, an all Federal dollars allocated to campuses were ti meet specific national needs.

There were two important exceptions: the GI Bill after World War 11, which crowded the colleges ant universities with returning servicemen and spent $1 billion on educational benefits, and the National Defense Education Act, which was the broadest leglation of its kind and the first to be based, at leas in part, on the premise that support of education in self is as much in the national interest as supporting which is based on the colleges' contributions to some thing as specific as the national defense.

The crucial turning-points were reached in the Kennedy-Johnson years. President Kennedy said "We pledge ourselves to seek a system of higher education where every young American can be educated, not according to his race or his means, but according to his capacity. Never in the life of this country has the pursuit of that goal become more important or more urgent." Here was a clear national commitment to universal higher education, a public acknowledgment that higher education is worthy of support for its own sake. The Kennedy and Johnson administrations produced legislation which authorized:

► $1.5 billion in matching funds for new construction on the nation's campuses.

► $ 151 million for local communities for the building of junior colleges.

► $432 million for new medical and dental schools and for aid to their students.

► The first large-scale Federal program of undergraduate scholarships, and the first Federal package combining them with loans and jobs to help individual students.

► Grants to strengthen college and university libraries.

► Grants to strengthen college and university libraries. promising institutions," in an effort to lift the entire system of higher education.

► The first significant support of the humanities. In addition, dozens of "Great Society" bills in- cluded funds for colleges and universities. And their number is likely to increase in the years ahead.

The full significance of the developments of the last few years will probably not be known for some time. But it is clear that the partnership between the Federal government and higher education has entered a new phase. The question of the Federal government's total relationship to colleges and universities-avoided for so many years—has still not been squarely faced. But a confrontation may be just around the corner.

4 new phase in government-campus relationships

THE MAJOR PITFALL, around which Presidents and Congressmen have detoured, is the issue of the separation of state and church. The Constitution of the United States says nothing about the Federal government's responsibility for education. So the rationale for Federal involvement, up to now, has been the Constitution's Article I, which grants Congress the power to spend tax money for the common defense and the general welfare of the nation.

So long as Federal support of education was specific in nature and linked to the national defense, the religious issue could be skirted. But as the emphasis moved to providing for the national welfare, the legal grounds became less firm, for the First Amendment to the Constitution says, in part, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion. ..."

So far, for practical and obvious reasons, neither the President nor Congress has met the problem head-on. But the battle has been joined, anyway. Some cases challenging grants to church-related colleges are now in the courts. And Congress is being pressed to pass legislation that would permit a citizen to challenge, in the Federal courts, the Congressional acts relating to higher education.

Meanwhile, America's 893 church-related colleges are eligible for funds under most Federal programs supporting higher education, and nearly all have received such funds. Most of these institutions would applaud a decision permitting the support to continue.

Some, however, would not. The Southern Baptists and the Seventh Day Adventists, for instance, have opposed Federal aid to the colleges and universities related to their denominations. Furman University, for example, under pressure from the South Carolina Baptist convention, returned a $612,000 Federal grant that it had applied for and received. Many colleges are awaiting the report of a Southern Baptist study group, due this summer.

Such institutions face an agonizing dilemma: stand fast on the principle of separation of church and state and take the financial consequences, or join the majority of colleges and universities and risk Federal influence. Said one delegate to the Southern Baptist Convention: "Those who say we're going to become second-rate schools unless we take Federal funds see clearly. I'm beginning to see it so clearly it's almost a nightmarish thing. I've moved toward Federal aid reluctantly; I don't like it."

Some colleges and universities, while refusing Federal aid in principle, permit some exceptions. Wheaton College, in Illinois, is a hold-out; but it allows some of its professors to accept National Science Foundation research grants. So does Rockford College, in Illinois. Others shun government money, but let their students accept Federal scholarships and loans. The president of one small churchrelated college, faced with acute financial problems, says simply: "The basic issue for us is survival."

Is higher education losing

RECENT FEDERAL PROGRAMS have sharpened the conflict between Washington and the states in fixing the responsibility for education. Traditionally and constitutionally, the responsibility has generally been with the states. But as Federal support has equaled and surpassed the state allocations to higher education, the question of responsibility is less clear.

The great growth in quality and Ph.D. production of many state universities, for instance, is undoubtedly due in large measure to Federal support. Federal dollars pay for most of the scientific research in state universities, make possible higher salaries which attract outstanding scholars, contribute substantially to new buildings, and provide large amounts of student aid. Clark Kerr speaks of the "Federal grant university," and the University of California (which he used to head) is an apt example: nearlyhalf of its total income comes from Washington.

To most governors and state legislators, the Fed- eral grants are a mixed blessing. Although they have helped raise the quality and capabilities of state institutions, the grants have also raised the pressure on state governments to increase their appropriations for higher education, if for no other reason than to fulfill the matching requirement of many Federal awards. But even funds which are not channeled through the state agencies and do not require the state to provide matching funds can give impetus to increased appropriations for higher education. Federal research grants to individual scholars, for example, may make it necessary for the state to provide more faculty members to get the teaching done.

Last year, 38 states and territories joined the Compact for Education, an interstate organization designed to provide "close and continuing consultation among our several states on all matters of education." The operating arm of the Compact will gather information, conduct research, seek to improve standards, propose policies, "and do such things as may be necessary or incidental to the administration of its authority. ..."

Although not spelled out in the formal language of the document, the Compact is clearly intended to enable the states to present a united front on the future of Federal aid to education.

IN TYPICALLY PRAGMATIC FASHION, we Americans want our colleges and universities to serve the public interest. We expect them to train enough doctors, lawyers, and engineers. We expect them to provide answers to immediate problems such as water and air pollution, urban blight, national defense, and disease. As we have done so often in the past, we expect the Federal government to build a creative and democratic system that will accomplish these things.

A faculty planning committee at one university stated in its report: "... A university is now regarded as a symbol for our age, the crucible in which —by some mysterious alchemy—man's long-awaited Utopia will at last be forged."

Some think the Federal role in higher education is growing too rapidly.

As early as 1952, the Association of American Universities' commission on financing higher education warned: "We as a nation should call a halt at this time to the introduction of new programs of direct Federal aid to colleges and universities. . . . Higher education at least needs time to digest what it has already undertaken and to evaluate the full impact of what it is already doing under Federal assistance." The recommendation went unheeded.

A year or so ago, Representative Edith Green of Oregon, an active architect of major education legislation, echoed this sentiment. The time has come, she said, "to stop, look, and listen," to evaluate the impact of Congressional action on the educational system. It seems safe to predict that Mrs. Green's warning, like that of the university presidents, will fail to halt the growth of Federal spending on the campus. But the note of caution she sounds will be well-taken by many who are increasingly concerned about the impact of the Federal involvement in higher education.

The more pessimistic observers fear direct Federal control of higher education. With the loyalty-oath conflict in mind, they see peril in the requirement that Federally supported colleges and universities demonstrate compliance with civil rights legislation or lose their Federal support. They express alarm at recent agency anti-conflict-of-interest proposals that would require scholars who receive government support to account for all of their other activities.

For most who are concerned, however, the fear is not so much of direct Federal control as of Federal influence oii the conduct of American higher education. Their worry is not that the government will deliberately restrict the freedom of the scholar, or directly change an institution of higher learning. Rather, they are afraid the scholar may be tempted to confine his studies to areas where Federal support is known to be available, and that institutions will be unable to resist the lure of Federal dollars.

Before he became Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, John W. Gardner said: "When a government agency with money to spend approaches a university, it can usually purchase almost any service it wants. And many institutions still follow the old practice of looking on funds so received as gifts. They not only do not look a gift horse in the mouth; they do not even pause to note whether it is a horse or a boa constrictor."

THE GREATEST OBSTACLE to the success of the government-campus partnership may lie in the fact that the partners have different objectives.

The Federal government's support of higher education has been essentially pragmatic. The Federal agencies have a mission to fulfill. To the degree that the colleges and universities can help to fulfill that mission, the agencies provide support.

The Atomic Energy Commission, for example, supports research and related activities in nuclear physics; the National Institutes of Health provide funds for medical research; the Agency for International Development finances overseas programs. Even recent programs which tend to recognize higher education as a national resource in itself are basically presented as efforts to cope with pressing national problems.

The Higher Education Facilities Act, for instance, provides matching funds for the construction of academic buildings. But the awards under this program are made on the basis of projected increases in enrollment. In the award of National Defense Graduate Fellowships to institutions, enrollment expansion and the initiation of new graduate programs are the main criteria. Under new programs affecting medical and dental schools, much of the Federal money is intended to increase the number of practitioners. Even the National Humanities Endowment, which is the government's attempt to rectify an academic imbalance aggravated by massive Federal support for the sciences, is curiously and pragmatically oriented to fulfill a specific rhission, rather than to support the humanities generally because they are worthy in themselves.

Who can dispute the validity of such objectives? Surely not the institutions of higher learning, for they recognize an obligation to serve society by providing trained manpower and by conducting applied research. But colleges and universities have other traditional missions of at least equal importance. Basic research, though it may have no apparent relevance to society's immediate needs, is a primary (and almost exclusive) function of universities. It needs nO other justification than the scholar's curiosity. The department of classics is as important in the college as is the department of physics, even though it does not contribute to the national defense. And enrollment expansion is neither an inherent virtue nor a universal goal in higher educa- tion; in fact, some institutions can better fulfill their objectives by remaining relatively small and selective.

Colleges and universities believe, for the most part, that they themselves are the best judges of what they ought to do, where they would like to go, and what their internal academic priorities are. For this reason the National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges has advocated that the government increase its institutional (rather than individual project) support in higher education, thus permitting colleges and universities a reasonable latitude in using Federal funds.

Congress, however, considers that it can best determine what the nation's needs are, and how the taxpayer's money ought to be spent. Since there is never enough money to do everything that cries to be done, the choice between allocating Federal funds for cancer research or for classics is not a very difficult one for the nation's political leaders to make. "The fact is," says one professor, "that we are trying to merge two entirely different systems. The government is the political engine of our democracy and must be responsive to the wishes of the people. But scholarship is not very democratic. You don't vote on the laws of thermodynamics or take a poll on the speed of light. Academic freedom and tenure are not prizes in a popularity contest."

Some observers feel that such a merger cannot be accomplished without causing fundamental changes in colleges and universities. They point to existing academic imbalances, the teaching-versus-research controversy, the changing roles of both professor and student, the growing commitment of colleges and universities to applied research. They fear that the influx of Federal funds into higher education will so transform colleges and universities that the very qualities that made the partnership desirable and productive in the first place will be lost.

The great technological achievements of the past 30 years, for example, would have been impossible without the basic scientific research that preceded them. This research—much of it seemingly irrelevant to society's needs—was conducted in universities, because only there could the scholar find the freedom and support that were essential to his quest. If the growing demand for applied research is met at the expense of basic research, future generations may pay the penalty.

One could argue—and many do—that colleges and universities do not have to accept Federal funds. But, to most of the nation's colleges and universities, the rejection of Federal support is an unacceptable alternative.

For those institutions already dependent upon Federal dollars, it is too late to turn back. Their physical plant, their programs, their personnel are all geared to continuing Federal aid.

And for those institutions which have received only token help from Washington, Federal dollars offer the one real hope of meeting the educational objectives they have set for themselves.

When basic objectives differ, whose will prevail?

HOWEVER DISTASTEFUL the thought may be to those who oppose further Federal involvement in higher education, the fact is that there is no other way of getting the job done—to train the growing number of students, to conduct the basic research necessary to continued scientific progress, and to cope with society's most pressing problems.

Tuition, private contributions, and state alloca- tions together fall far short of meeting the total cost of American higher education. And as costs rise, the gap is likely to widen. Tuition has finally passed the $2,000 mark in several private colleges and univer- sities, and it is rising even in the publicly supported institutions. State governments have increased their appropriations for higher education dramatically, but there are scores of other urgent needs competing for state funds. Gifts from private foundations, corporations, and alumni continue to rise steadily, but the increases are not keeping pace with rising costs.

Hence the continuation and probably the enlargement of the partnership between the Federal government and higher education appears to be inevitable. The real task facing the nation is to make it work.

To that end, colleges and universities may have to become more deeply involved in politics. They will have to determine, more clearly than ever before, just what their objectives are—and what their values are. And they will have to communicate these most effectively to their alumni, their political representatives, the corporate community, the foundations, and the public at large.

If the partnership is to succeed, the Federal government will have to do more than provide funds. Elected officials and administrators face the awesome task of formulating overall educational and research goals, to give direction to the programs of Federal support. They must make more of an effort to understand what makes colleges and universities tick, and to accommodate individual institutional differences.

THE TAXPAYING PUBLIC, and particularly alumni and alumnae, will play a crucial role in the evolution of the partnership. The degree of their understanding and support will be reflected in future legislation. And, along with private foundations and corporations, alumni and other friends of higher education bear a special responsibility for providing colleges and universities with financial support. The growing role of the Federal government, says the president of a major oil company, makes corporate contributions to higher education more important than ever before; he feels that private support enables colleges and universities to maintain academic balance and to preserve their freedom and independence. The president of a university agrees: "It is essential that the critical core of our colleges and universities be financed with non-Federal funds."

"What is going on here," says McGeorge Bundy, "is a great adventure in the purpose and performance of a free people." The partnership between higher education and the Federal government, he believes, is an experiment in American democracy.

Essentially, it is an effort to combine the forces of our educational and political systems for the common good. And the partnership is distinctly American—boldly built step by step in full public view, inspired by visionaries, tested and tempered by honest skeptics, forged out of practical political compromise.

Does it involve risks? Of course it does. But what great adventure does not? Is it not by risk-taking that free—and intelligent—people progress?

Copyright 1967 by Editorial Projects for Education, Inc.

"Many institutions not only do not look a gift horse in the mouth; they do not even pause to note whetherit is a horse or a boa constrictor—JOHN GARDNER

Even those campuses which traditionally stand apart from government find it hard to resist Federal aid.

Some people fear that the colleges and universities arein danger of being remade in the Federal image.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDICK'S HOUSE

April 1967 -

Feature

FeatureUNCLE SAM AT DARTMOUTH

April 1967 By C. E. W. -

Article

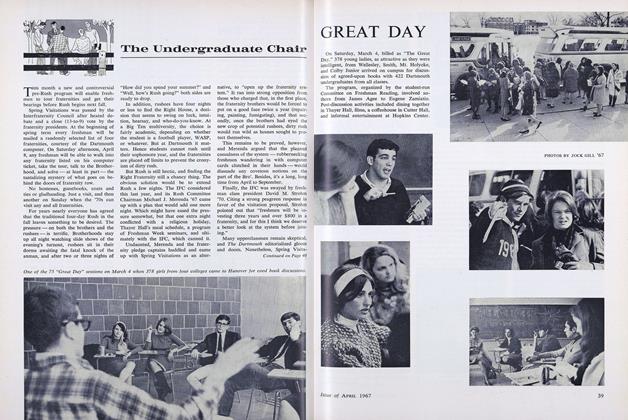

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleEloquence at Gettysburg and Daniel Webster

April 1967 By EARL W. WILEY '08 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

April 1967 By MACOMBER, JOHN s. MAYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

April 1967 By EARL H. COTTON, ROBERT G. THOMAS

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Priorities for 1970

MARCH 1970 -

Feature

FeatureCue the Millennium

NOVEMBER 1996 -

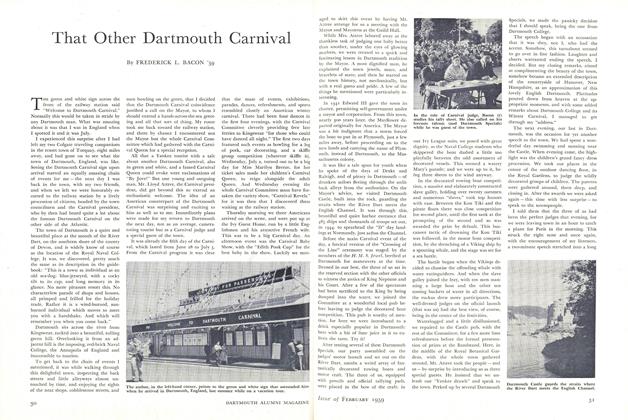

Feature

FeatureThat Other Dartmouth Carnival

FEBRUARY 1959 By FREDERICK L. BACON '59 -

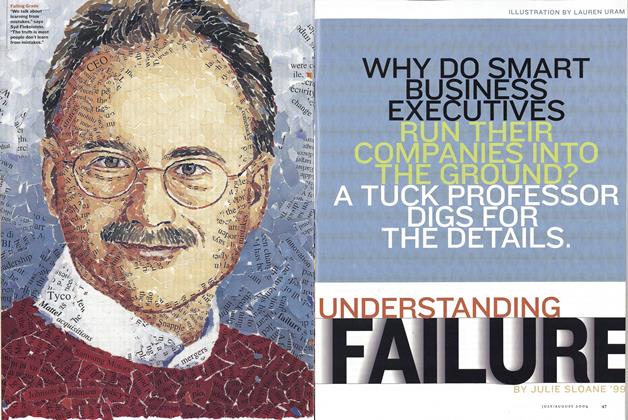

Feature

FeatureUnderstanding Failure

Jul/Aug 2004 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

FeatureRalph Sterner: See-er

May 1975 By RALPH STEINER -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWha is There to Teach About Art?

MAY 1996 By Rebecca Bailey