When Dick and I decided to undertake a new translation of Plato's Republic which would more effectively communicate its intellectual and artistic content to a modern reader - especially to today's student - we expected some skepticism. After all, there have been translations of this classic for centuries. One colleague dryly said he had heard somewhere that The Republic had already been translated. But it did not require much persuasion to convince some critics, at least, that the preservation of books from other languages and ages often requires periodic and lively representations. This holds true in particular for books like The Republic, whose complex and controversial arguments are an open invitation to repeated interpretation.

Translation is a complex process. Any version of a text from a foreign language is inevitably colored by one's own experience in the choice of words and phrasing as well as the accretion of alien connotations upon seemingly familiar concepts. Of course, the basic words for "dog" and "cat" are effortlessly brought over from one language to another; however, at the level of philosophy and ideology, imagine a discussion of justice among Plato, John Calvin, Thomas Jefferson, and Karl Marx. The preconceptions inherent in such a discussion and the resultant confusions will demonstrate how difficult the task of overcoming linguistic barriers and cultural diversity can be -and how important to a more profound understanding of civilization's fundamental concepts.

What follows is direct comparative evidence illustrating how much the language of translation can differ. We compare a single passage from two earlier and widely known translations with the identical passage in our version. The passage, in which Plato describes the just man, is from Book IV of The Republic, 443 c-e.

The best known translation of Plato's Republic for the past 100 years is by Benjamin Jowett of Balliol College, Oxford (1871). Even today his version remains clear, elegant, and often lively in expression; however, Jowett's choice of words and phrasing reflects the sometimes ponderous style of Victorian England. So do the length and complexity of his Sentences:

But in reality justice was such as we were describing, being concerned, however, not with the outward man, but with the inward, which is the true self and concernment of man: for the just man does not permit the several elements within him to interfere with one another, or any of them to do the work of others, he sets in order his own inner life, and is his own master and his own law, and at peace with himself; and when he has bound together the three principles within him, which may be compared to the higher, lower, and middle notes of the scale, and the intermediate intervals when he has bound all these together, . . . [he] ... is no longer many, but has become one entirely temperate and perfectly adjusted nature . . .

The 1968 translation of Allan Bloom has remained a standard in the classroom since its publication. Bloom is strict in his adherence to Plato's text and uncompromisingly literal in his rendition of Greek phrasing. Yet Bloom's English is difficult to read because it so closely approximates the original that there are places where the Greek structure seems to get in the way of clear English expression:

And in truth justice was, as it seems, something of this sort; however, not with respect to a man's minding his external business, but with respect to what is within, with respect to what truly concerns him and his own. He doesn't let each part in him mind other people's business or the three classes in the soul meddle with each other, but really sets his own house in good order and rules himself; he arranges himself, becomes his own friend, and harmonizes the three parts, exactly like three notes in a harmonic scale, lowest, highest and middle. And if there are some other parts in between, he binds them together and becomes entirely one from many, moderate and harmonized.

In our version we have attempted to sharpen the clarity of the argument by several means. We often use several shorter sentences to represent the original phrasing, which typically employs very long sentences linked by participles. We have used standard English word order throughout. We have employed a vocabulary which is readily understandable to today's reader in an effort to convey the simplicity and elegance of Plato's Greek into clear English:

The reality is that justice is not a matter of external behavior but the way a man privately and truly governs his inner self. The just man does not permit the various parts of his soul to interfere with one another or usurp each other's functions. He has set his own life in order. He is his own master and his own law. He has become a friend to himself. He will have brought into tune the three parts of his soul: high, middle and low, like the three major notes of a musical scale, and all the intervals between. When he has brought all this together in temperance and harmony he will have made himself one man instead of many.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn the Air

December 1985 By Michael Berg '82 -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

December 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Cover Story

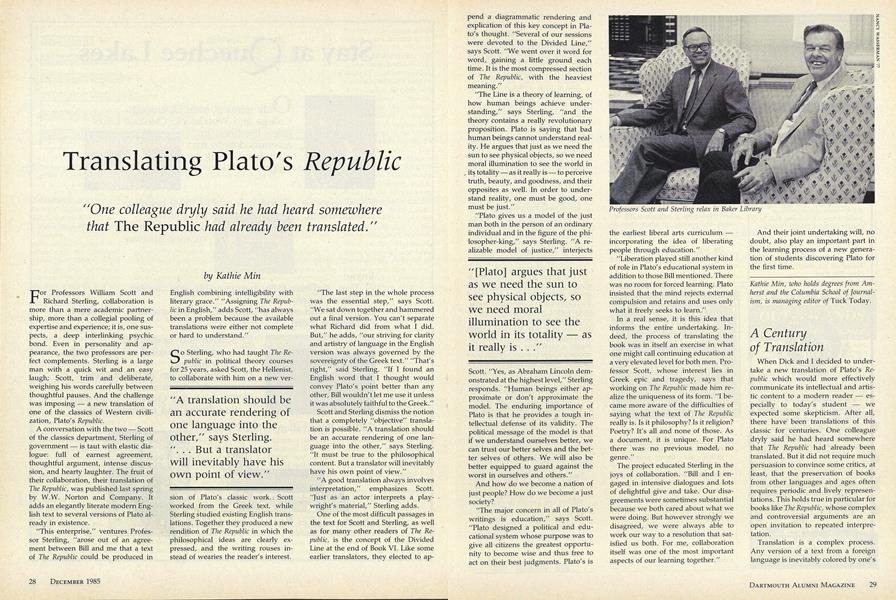

Cover StoryTranslating Plato's Republic

December 1985 By Kathie Min -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFragments of papyrus

December 1985 By RICHARD W. STERLING -

Article

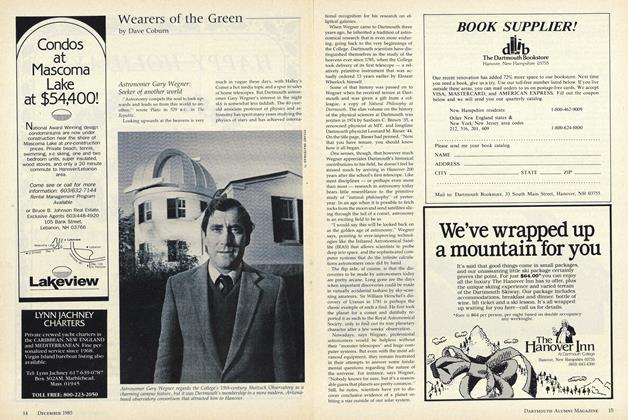

ArticleAstronomer Gary Wegner: Seeker of another world

December 1985 By Dave Coburn -

Sports

SportsThe Man Behind the Berry Sports Center

December 1985 By Jim Kenyon

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Marxist View of Overpopulation

JUNE 1971 By Charles W. Collier '71 -

Feature

FeatureConquest of the Antarctic

June 1957 By DAVID C. NUTT '41 -

Feature

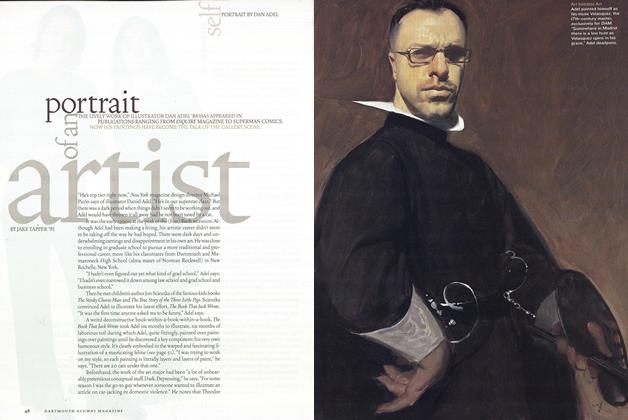

FeaturePortrait of an Artist

Mar/Apr 2003 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMiraculously Builded In Our Hearts

MARCH 1991 By Judson D. Hale '55 -

Cover Story

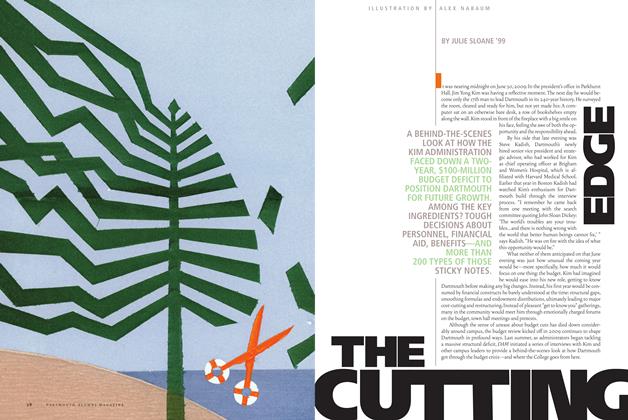

Cover StoryThe Cutting Edge

May/June 2011 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

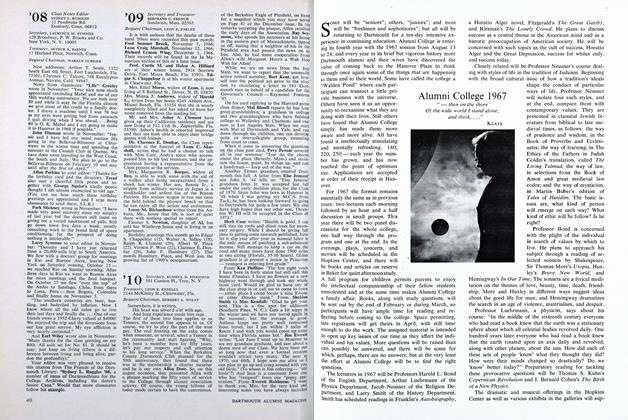

FeatureAlumni College 1967

JANUARY 1967 By KEATS