RAPHAEL HILLYER '36, the Juilliard String Quartet violist, performs in 175 concerts a year and still plays many additional hours "for the fun of it."

Hillyer, who has an enduring craggy face that belongs in bronze, recently returned to Hanover with the Quartet for a well-received Hopkins Center concert. He recalled then that when he came here in 1946 for his tenth reunion, he and three other members of the Juilliard faculty remained over the summer, rehearsing for two concerts to be given at the end of the season in Robinson Hall. Although commissioned by Juilliard to form the group, they were not allowed to call themselves the "Juilliard String Quartet" until they had proven themselves. That did not take long.

The Quartet was on the road 290 days last year. As Quartet-in-Residence at Juilliard the members are on the faculty there, teaching and consulting two days a week. They are also Quartet-in-Residence at the Library of Congress, and as such they give two six-week concert series there annually and are privileged to play the instruments in the Library's priceless Whithall Stradivarius Collection.

"We're often asked if the instruments we use on tour are the Strads," Hillyer said, "but we're not allowed to remove those from the Library."

Four months of their concert tour last year were spent in the Far East. Under the auspices of the State Department and Pan American Airways the Quartet established schools in Korea and Japan, a historic first for chamber music in that area.

It wasn't the first time, however, that the Quartet had acted as cultural ambassadors for the Government. Hillyer's interest in languages and his remarks to audiences in Japanese, Russian, and Korean have won them great rapport.

Hillyer described some interesting contrasts among foreign audiences:

"A Scandinavian audience might be very appreciative," he comments, "but unless you know what to expect you might not interpret their restrained response that way.

"Hungarians, on the other hand, can be wildly enthusiastic. The German and big-city American audiences are the most discerning. Japanese critics and audiences are notorious for being hypercritical."

In the Soviet Union in 1965, after a brilliant but exhausting performance, they were recalled for encore after encore.

"Finally," Hillyer said, "two of our members who had their families backstage carried their sleeping children onstage. That stopped the encores."

Usually they release three two-sided records annually. The Quartet's best sellers are the series of six Bartók quartets which won a recording industry award. Three recordings are now "on ice" waiting to be released - two with Leonard Bernstein, one with Glenn Gould.

In addition to these virtuosos, Hillyer has performed with the Boston Symphony under Serge Koussevitsky (very early in his career) and the NBC Symphony under Arturo Toscanini. Before coming to Dartmouth he had studied music at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia. A math major and Senior Fellow, he went on to Harvard for an M.A.

When Hillyer and his Japanese wife are not traveling to her country on a talent hunt or to collect oriental art, they frequently entertain students in their home for late-night musicales.

"I find it surprising," he said, "that many musicians don't play for their own entertainment."

He does, and a knowledge of his early home life makes this dedication understandable. His mother was a concert pianist and teacher. His father Louis Silverman, Dartmouth Professor Emeritus of Mathematics, now at the University of Houston, played viola. Professor Silverman maintains that mathematicians who have an interest in music are common phenomena. He calls them "mathemusicians." His son turned out to be a virtuoso example.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureLife with Uncle

April 1967 -

Feature

FeatureDICK'S HOUSE

April 1967 -

Feature

FeatureUNCLE SAM AT DARTMOUTH

April 1967 By C. E. W. -

Article

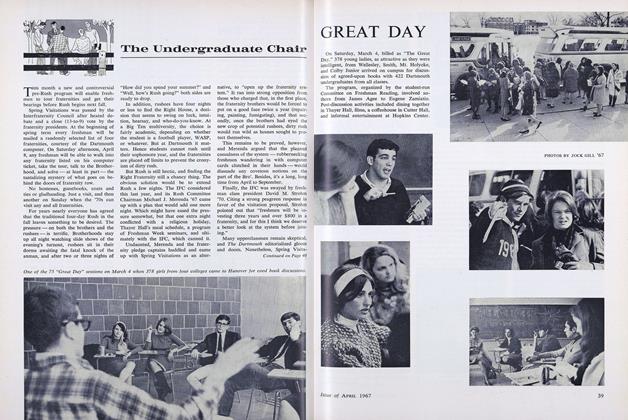

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleEloquence at Gettysburg and Daniel Webster

April 1967 By EARL W. WILEY '08 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

April 1967 By MACOMBER, JOHN s. MAYER

Article

-

Article

ArticleGROUP OF FRATERNITIES BUILDS NEW YORK CLUB

December, 1922 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

May 1952 -

Article

ArticleGive A Rouse for –

March 1974 -

Article

ArticleWinter Sports Activities

January 1949 By John R. Zillmer '48 -

Article

ArticleProfessor of Economics William L. Baldwin

NOVEMBER 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSTILL SEEKS A PRIZE SONG

By WELD A. ROLLINS '97