"Sobering Evidence"

TO THE EDITOR:

The two answers (in the March issue) to Edward Holmes' criticism of our Vietnam policy are, I'm afraid, sobering evidence of what twenty years of cold war have done to otherwise thoughtful and intelligent men. From them, we learn (1) that United States involvement in Vietnam can somehow be equated with Vietnamese involvement in Vietnam, and (2) that our own war crimes are more excusable because they "came after" German and Japanese crimes. As grotesque as the first position may seem, it's certainly a product of anti-Communist pathology, on a plane with John Foster Dulles' April 1954 suggestion that "a Communist victory in Vietnam, even if achievedwith Vietnam forces alone, is not to be tolerated." As for the second, I might simply point out that the French writer FranÇois Mauriac condemned his own country's outrages in Algeria as worse than the Nazi crimes - precisely because decent men should have learned their lesson from Auschwitz and Dachau, as well as from Dresden and Hiroshima.

Bryn Mawr, Pa.

A Reply to Replies

TO THE EDITOR:

Parts of Mr. Fanelli's and Mr. Chemontowski's letters replying to mine in the January issue command my respect. Reading other parts was like seeing my image in a distorted mirror, though whether it is I, the mirror, or the medium between - our writing and our reading - that is twisted, others, no doubt, are best equipped to judge.

Restricted to the relative brevity of a publishable letter, I condensed my initial communication, painting with broad brush strokes. The harsh, unexplained colors offended the repliers' sense of reasoned discourse, and I appreciate their distress.

Reviewing the situation in Vietnam as it apparently stands now, one wonders if the citizen of any small country can envision a harsher fate for his land than having the United States save it from aggression. Do we persist because the end really does justify our means? Or are we too proud to admit that in this international action we have quite possibly been wrong?

Old Town, Maine

Failure in the Forties

TO THE EDITOR: President Dickey's reply* to those of the Class of 1945 who are upset by Dartmouth faculty members' statements concerning the United States' involvement in Vietnam states very well the position of a college or university

on academic freedom. Indeed, it would be a serious matter if institutions of higher learning were determined in their policies and views by alumni or by the population at large.

Another issue remains, however, an issue of great concern to all of us who attended Dartmouth in the forties: why is it that so many of the Class of 1945 express the views they do? The attitudes toward faculty and toward the school from which these critics graduated suggest that either Dartmouth failed them grievously, or that they, because of the circumstances of their peculiar war-relationship to their College, never were able to benefit from the training Dartmouth was supposed to provide. I believe the reason for their confusion about basic academic issues and about the role of a college is due to the unfortunate conditions of the college education they expected but never received. For most of us the Dartmouth years were unhappily broken by the war; most of us went off to military service, and many of Dartmouth's best teachers also left in a variety of military and civilian capacities. The war took our energies, and those years when ordinarily we would have been studying at Dartmouth were interrupted and shortened. Those of us who returned to finish up after the war had family and career obligations which again made the Dartmouth experience attenuated. In short, we were one of the most unfortunate of Dartmouth classes.

What is it that the letters received by and large show? To me they show a class sadly undereducated; unable to see that the trained mind can consider alternative positions, and can defend the expression of views other than its own, even when those views appear to be misguided or wrong. The statements made about the war and about the conditions of life in the United States express the most banal, the most routine, unreflective acceptance of the majority. While these positions may be defended reasonably, they are not so defended, but merely asserted as if enthusiasm must carry the argument. It does not. Further, the views show a shocking misunderstanding of what goes on and ought to go on in a free society of searching minds. Dartmouth is not the local newspaper, or the lobby in Washington, or the club; it is an institution devoted to free inquiry and to scholarship and to teaching. As such it has an obligation to examine, to explore, to test a great variety of positions. And its teachers have the opportunity and indeed the right to explore problems confronting the United States in all its internal and external affairs. It is from such institutions that solutions and constructive ideas come. No one ought to know that better than Dartmouth's own alumni. And it is indeed shocking to see that, for some of the alumni at least, what Dartmouth should and can do is sadly misunderstood. I can only conclude that this is the case because the war years weakened and diminished what should have been a full and exciting and liberating undergraduate experience. That we were denied this is one of the serious and debilitating consequences of World War II. I think that alone ought to lead us to consider carefully the consequences of war.

Professor of PhilosophyColumbia University

* In his letter President Dickey wrote:

"I respect your right to disagree with anyone, including of course myself, but I do not believe you or anyone else would for long like or support an institution of higher education where the responsible officers of the faculty and staff looked to some outside 'majority' or other authority for guidance as to what they thought and said.

"As for 'the College's tacit consent' in the positions taken by groups of students, professors - or alumni - this is simply not so. The consent, tacit or otherwise, is simply to such groups or individuals having their own say. Incidentally, I also have my say through my utterances at Convocation and on other occasions. If you have followed my published statements over the years you must be aware that I frequently have a quite different position than that of others who are connected in some way with the College."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

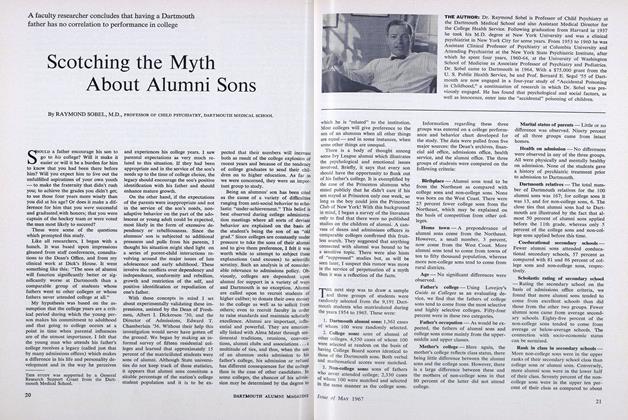

FeatureScotching the Myth About Alumni Sons

May 1967 By RAYMOND SOBEL, M.D. -

Feature

FeatureThe Humanistic Pursuit of Values

May 1967 By ROBIN J. SCROGGS -

Feature

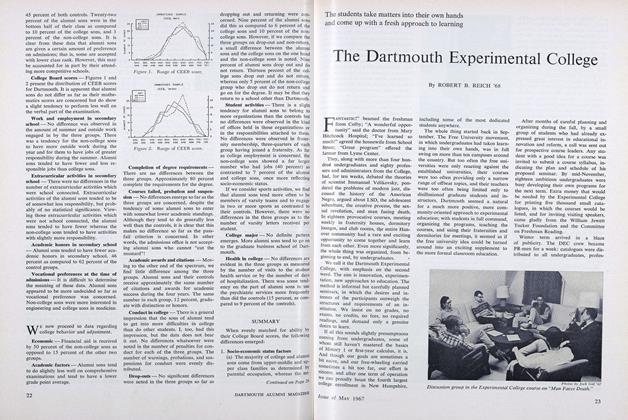

FeatureThe Dartmouth Experimental College

May 1967 By ROBERT B. REICH '68 -

Feature

FeatureRefugees' Friend

May 1967 -

Feature

FeatureManhattan Realtor

May 1967 -

Feature

FeatureBotanic Director

May 1967

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorSOME DARTMOUTH LETTERS OF 100 YEARS AGO

December, 1922 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorImportant Invention

June 1938 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

May 1979 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Nov/Dec 2009 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Jan/Feb 2011 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Sept/Oct 2011