The students take matters into their own hands and come up with a fresh approach to learning

FANTASTIC!" beamed the freshman from Colby; "A wonderful opportunity" said the doctor from Mary Hitchcock Hospital; "I've learned so much!" agreed the housewife from School Street; "Great program" offered the farmer from Lyme Center.

They, along with more than four hundred undergraduates and eighty professors and administrators from the College, had, for ten weeks, debated the theories of scientist Immanuel Velikovsky, pondered the problems of modern jazz, discussed the history of the American Negro, argued about LSD, the adolescent subculture, the creative process, the sexual revolution, and man facing death. In eighteen provocative courses, meeting weekly in fraternity houses, dormitory lounges, and club rooms, the entire Hanover community had a rare and exciting opportunity to come together and learn from each other. Even more significantly, the whole thing was organized, from beginning to end, by undergraduates.

We call it the Dartmouth Experimental College, with emphasis on the second word. The aim is innovation, experimentation, new approaches to education. The method is informal but carefully planned seminars, in which the desires and interests of the participants outweigh the structures and requirements of an institution. We insist on no grades, no exams, no credits, no fees, no required readings, and demand only a genuine desire to learn.

If all this sounds slightly presumptuous coming from undergraduates, some of whom still haven't mastered the basics of History 1 or first-year calculus, it is. And though our goals are sometimes a it naive, and our free-wheeling carried sometimes a bit too far, our effort is sincere; and after one term of operation We can proudly boast the fourth largest college enrollment in New Hampshire, including some of the most dedicated students anywhere.

The whole thing started back in September. The Free University movement, in which undergraduates had taken learning into their own hands, was in full swing on more than ten campuses around the country. But too often the free universities were only reacting against the established universities, their courses were too often providing only a narrow range of offbeat topics, and their teachers were too often being limited only to disillusioned graduate students and instructors. Dartmouth seemed a natural for a much more positive, more community-oriented approach to experimental education; with students in full command, organizing the programs, teaching the courses, and using their fraternities and dormitories for meetings, it seemed as if the free university idea could be turned around into an exciting supplement to the more formal classroom education.

After months of careful planning and organizing during the fall, by a small group of students who had already expressed great interest in educational innovation and reform, a call was sent out for prospective course leaders. Any student with a good idea for a course was invited to submit a course syllabus, indicating the plan and schedule of his proposed seminar. By mid-November, eighteen ambitious undergraduates were busy developing their own programs for the next term. Extra money that would be needed by the Experimental College for printing five thousand small catalogues, in which the courses would be listed, and for inviting visiting speakers, came gladly from the William Jewett Tucker Foundation and the Committee on Freshman Reading.

Winter term arrived in a blaze of publicity. The DEC crew became PR-men for a week: catalogues were distributed to all undergraduates, professorns, faculty wives, and many townspeople; posters, radio interviews, local television features, newspaper articles, were all planned in a large-scale attempt to round up interested participants from all over the Upper Valley. Apparently we did a good job - too good. Over 1200 enthusiastic applications flooded our little office in the basement of Webster Hall, including registrations from over half of Colby Junior College.

The problem we never expected became an embarrassing reality. The hope had been to keep the classes intimate, conducive to intense discussion and informal lectures. But eighteen courses could never accommodate 1200 participants, no matter how enthusiastic. Amid outcries against creeping bureaucracy and Ivy League admissions standards, the huge pile of applications was somehow reduced, and 700 were arbitrarily selected to take part in the experiment. Dartmouth's own admissions director, Edward Chamberlain, just squeezed in, and we blushingly had to refuse over fifty young ladies from Colby.

But the smoke cleared, those who didn't gain admittance decided to wait until next term, and by mid-January, the Dartmouth Experimental College was a reality.

EVERY weekday night of the winter term saw fraternities and dormitories hosting lively discussions, supplemented by films, lectures, voluntary readings, and panel discussions. College faculty and other local experts provided their own specialized knowledge whenever appropriate, but students carried the ball.

Ronald Silverman '69 coordinated an exciting ten-week seminar based on the controversial works of scientist-philosopher Immanuel Velikovsky. "It was a lot of work," said Ron, "but tremendously worthwhile. Velikovsky's theories cover so many areas, I had to do months of research and digging before I started the course, and even then I wasn't completely ready." Ron invited professors from various departments of the College to discuss the relationship of their own fields to Velikovsky's work, and sessions were also highlighted by visiting scientists. Every Tuesday evening, Cutter Hall lounge was the scene of intense debate and fiery discussion. Gordon Atwater, former director of New York's Hay den Planetarium, gave the seminar an emotional recounting of his dismissal from the Planetarium in the early 50's, after he had publicly supported Velikovsky. Dr. Velikovsky himself climaxed the course with a stimulating two-day visitation to the campus. "The seminar was breathtaking in its scope, tremendously demanding in the depth of understanding required to keep up," said Colby senior Gail Curik, "but I took the bus from Colby every week because is was just - well - terrific!" Mrs. Albert I. Dickerson, wife of Dartmouth's dean of freshmen, agreed: "The discussions were absolutely fantastic!"

Cutter Hall wasn't the only place where things were happening. On the other side of campus, Alpha Chi Alpha fraternity hosted an equally exciting series of meetings dealing with the problem of law and the individual conscience. Steve Danford '67 coordinated this one, and the sessions included lectures by President Dickey and government professor Vincent Starzinger. John Patrick '69 led Pi Lam's popular and fascinating investigation of the world of LSD, and invited LSD expert Ralph Metzner in to discuss some unknown implications of the drug.

Meanwhile, way over in the wilds of Wigwam Circle, McLane Hall's commons room and Jon Reich '68 set the tone for a relaxed seminar focussing on the fantastic fiction of J. R. R. Tolkein. English professor Alan Gaylord, a loyal Tolkein fan, didn't miss a session, and praised the quality of student lecturing. "It's a real pleasure to hear an undergraduate deliver a talk for a change," said Mr. Gaylord. "I learned something!"

Jim Patrick '67 conducted a popular series on modern jazz every Sunday evening, using Hopkins Center's Buck Concert Lounge. He was helped by Jim Johnson '68 who gave jazz examples on the piano, and The Barbary Coast student jazz group who occasionally offered their own interpretations. "Most of the lectures were way over my head," admitted Rick Greffe '67, when the course was over, "but I got a lot out of it. Those guys really know their stuff."

The exciting thing was that the guys did know their stuff. Dartmouth Conservative Society's Bill Lind '69 lectured and led discussions on the development of Conservative thought; computer expert Ron Martin '67 introduced a large group to the world of the computer; economics major Jack Ferrare '67 coordinated a popular seminar on the workings of the stock market. "It's amazing how many interests and abilities of undergraduates have been brought out into the open through this program," commented Jim Payne '68, one of the original DEC organizers. "We can all share in their enthusiasm - and it's not just undergraduates who are learning from each other. In the DEC, student has come to mean almost anyone."

JIM was right. Student had come to mean housewives, merchants, lawyers, farmers, administrators, and teachers. In many instances, true "communities of scholars" had been created. The aim of the Experimental College had been to strip education to its bare and most meaningful essentials — to make it voluntary, unpressured, and truly enjoyable. One important feature of this aim was to be the cross-section of individuals who, we hoped, would take advantage of the program. We believed that education could be so much more meaningful when shared among a wide range of ages, occupations, and backgrounds, and when partaken by both sexes. The results more than proved our point. Discussions in the seminars, according to many undergraduate participants, achieved a new level of excitement and interest. "After a while, we gained respect for one another simply on the basis of what we had to contribute to the discussion," said Steven Stonefield '70. "It was quite an experience."

In many instances, the distinction between undergraduate and professor, between town and gown, completely dissolved. Mrs. Anne Frey, of School Street in Hanover, entertained her "classmates" with several small parties at her house, and called the DEC program "... a wonderful opportunity for the whole community!" The Dartmouth praised the results of the DEC's first term: "The DEC has done much to improve the image of the Dartmouth student to residents of the surrounding area. Moreover, in the area of student-faculty relations, the DEC has taken a significant forward step. The DEC has proven itself to be a vital and meaningful part of Dartmouth life."

Yet despite the apparent success, the first term of the Dartmouth Experimental College had met with several unforeseen problems. Undergraduate attendance, particularly around exam times, decreased considerably in several experimental courses. Occasionally, guest speakers never showed up and quick substitutes had to be found. Many Colby girls discovered that the cost of bus transportation to and from Hanover every week was just too great a financial sacrifice. In fact, money continued to be a problem through the term for all of us. Our resources were relatively small and our bills relatively large. Somehow we ended the term, still in the black. Better still, over 75% of the term's participants indicated, on our questionnaire, that they had had a tremendously rewarding experience and would definitely participate again.

Our ambition was renewed and our faith in the idea confirmed. New courses were prepared for the spring term, and once again the Experimental College set out to prove how meaningful education could be. Now another large group of Dartmouth students, professors, townspeople, and Colby Junior College girls are discussing and debating in 21 experimental courses around the campus. This term, investigations are being made into the Cuban Revolution, Guerilla Warfare, Gambling in the United States, the Advertising Game, Poverty in America, Contemporary Religion, Utopian Societies, United Nations Peacekeeping, the Criminal in Society, Anarchism, the Underground Film, and Peasant Revolutions. Two intensive experimental language courses are being tried out - one in Arabic and another in Japanese; and the Peace Corps is offering a course on race contact and the "White Man's Burden," including in its line-up of lecturers, Frank Mankiewicz, now press secretary to Robert Kennedy. Finally, three of the more popular courses from the winter term are being held over.

WHAT'S the future of all this? The Dartmouth Experimental College is obviously fulfilling a need at Dartmouth. It has become more obvious than ever that education must go beyond the classroom lecture and assigned readings, that the Dartmouth experience must come to mean more than 36 courses and twelve big weekends, that our undergraduate learning must transcend the superficialities of grades, credits, and exams. A program of informal, community oriented seminars, conducted by undergraduates in their own dormitories and fraternities, and centered upon provocative and relevant topics, has provided part of the answer.

Our hope is that the DEC will continue to supplement Dartmouth's formal learning process with fresh ideas and new approaches to education. There will always be a need for memorizing the dates and battles of History 1 or conquering the principles of first-year calculus; but there is also a need - a serious need - for the entire community to join together as students, and learn together in a pure, relaxed, informal, and sincere quest of new knowledge.

Discussion group in the Experimental College course on "Man Faces Death."

Scientist Immanuel Velikovsky (left) debates his theories with DEC class.

Guest lecturer John U. Harris '53 speaking to the Stock Market class.

Course leaders sorting out the heavy registration for spring term

THE AUTHOR: Bob Reich '68 (shown putting stickers on DEC catalogues) is an intellectual and extracurricular dynamo who has been making things happen on campus ever since he arrived as a freshman. This year's Experimental College, one of the best organized and most successful on any campus, is a good example of his ability to initiate and carry through worthwhile projects. A National Merit Scholar, he has been president of his class all three years and has just been named a Senior Fellow for 1967-68. Two years ago he won the Churchill Prize as the outstanding member of the freshman class and last year he received the Milton Sims Kramer Prize as the member of the three lower classes who has contributed the most to Dartmouth. As part of his extraordinary record to date, he has been personnel manager and newscaster for WDCR, a Jacko artist, an ABC tutor, a member of the Undergraduate Council and Green Key, winner of the Class of 1866 Oratorical Prize, author of an original play that won second prize in the annual Frost contest, and a member of the Hopkins Center Design Associates. Reich comes from South Salem, N. Y., and is the son of Edwin S. Reich '35.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

ROBERT B. REICH '68

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHANOVER SUMMER

September 1976 -

Feature

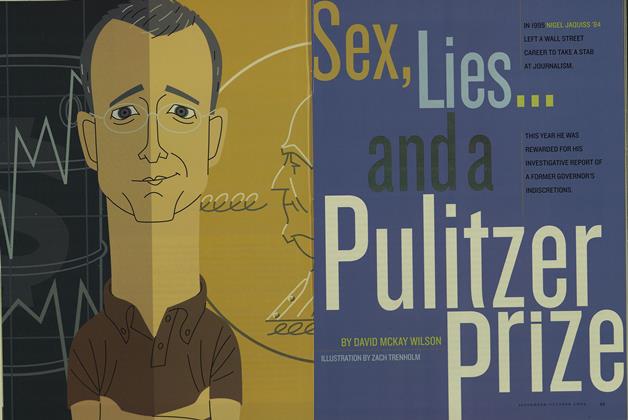

FeatureSex, Lies... and a Pulitzer Prize

Sept/Oct 2005 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMariam Malik '98

OCTOBER 1997 By Deborah Solomon -

Cover Story

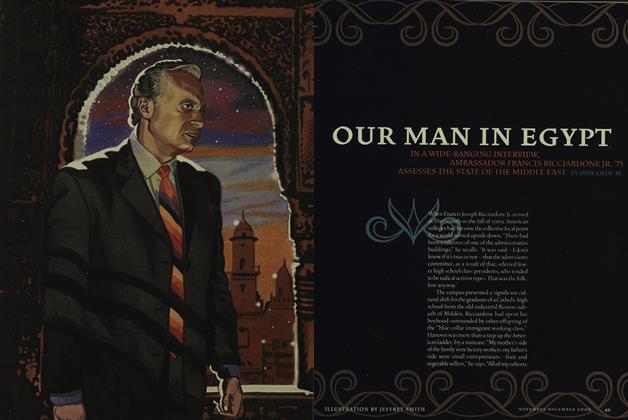

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

Nov/Dec 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureA Place In the Country

January 1975 By KENNETH A. JOHNSON -

Feature

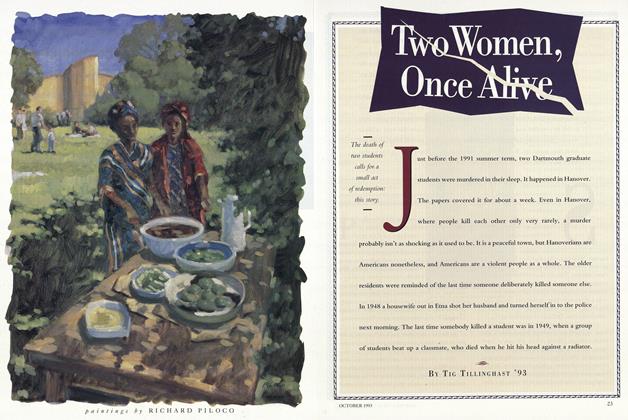

FeatureTwo Women, Once Alive

October 1993 By Tig Tillinghast '93