By Harold E. Burtt '11. New York:The Macmillan Co., 1967. 242 pp. $5.95.

There are various ways of writing a review. A commendable one, no doubt, is to have empathy for the writer as well as the prospective readers of his book; what, in short, does the writer aim at and does he get the message across? A second approach to book reviewing is for the reviewer to seize an opportunity to air his own opinions and prejudices. The present reviewer of Burtt's The Psychology of Birds has sought to attain balance. One has to realize, however, that on ideas regarding life and the workings of the mind, whether of man or birds, the art is long, experiment difficult, and judgment often perilous. As Von Frisch has shown, even the mind of such small creatures as dancing bees is exceedingly complicated to understand.

Dr. Burtt's outlook on problems of this type, however, is refreshingly simple. As chairman of a department of psychology for many years he knows that we can map out, analyze, and classify human personalities and intelligence by properly designed methods. Now in his retirement, he has applied these methods to birds. Of course one needs firsthand experience, but this has been gained by trapping and banding wild birds, no less than 17,000 of them. Dr. Burtt's book contains various observations made on these banding experiences, but it consists largely of reports culled from various ornithological journals on bird behavior or as he calls it, "psychology."

Every item is neatly labeled and interpreted in the light of scientific psychology and, read as a small encyclopedia, the book contains much of interest. One can enjoy such bits of information as the fact that the eyes of a Great Horned Owl are about the same size as ours, although the bird only weighs three or four pounds; or that the purple sandpiper of the arctic fluffs up its feathers and zig-zags over ground vegetation, making small noises as though it were a lemming, to decoy approaching predators away from its nest and eggs. The compilation of accounts of such curiosities of behavior makes good reading. It fills the mind with facts. A favorite paragraph of this reviewer is one on the Green Heron that put bread into the water and ate the fish that were attracted to it as "bait." This would seem like a clear case of putting two and two together. If a chimpanzee had done anything comparable, such as using a stick to reach a banana, we would say that this was pre-human intelligence. But alas for the birds. Dr. Burtt continually steps in with a reminder that science has found otherwise for them. Birds are only creatures, for the most part, of blind instinct, and it is a wonder that their mechanical behavior enables them to survive as well as they do. Man it appears, is unique, and birds are simple stereotypes in comparison.

There appears to be a few considerations missing here and there in the precise analyses offered by Dr. Burtt. One misses all the fullness of life and beauty, for example, in birds observed by field naturalists who have studied them in relation to their natural environments and who, like Konrad Lorenz in King Solomon's Ring or even Charles Darwin in his Expression of the Emotions inAnimals and Man have shown what an immense amount we can learn by the study of birds and other creatures, if we are ready to get to know the details of how they actually live. Academic spectacles are only one way of viewing the world. Dr. Burtt might, in fact, have written a more enlivening book had he followed Goth's advice of "one look at books and two looks at nature."

Professor of Microbiology

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

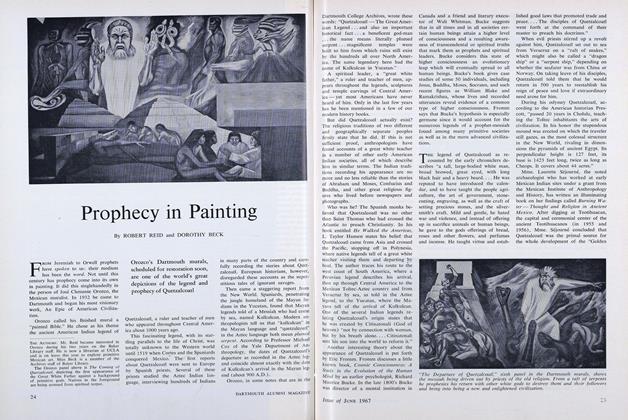

FeatureProphecy in Painting

June 1967 By ROBERT REID and DOROTHY BECK -

Feature

FeatureThe Wallace Affair

June 1967 By C.E.W. -

Feature

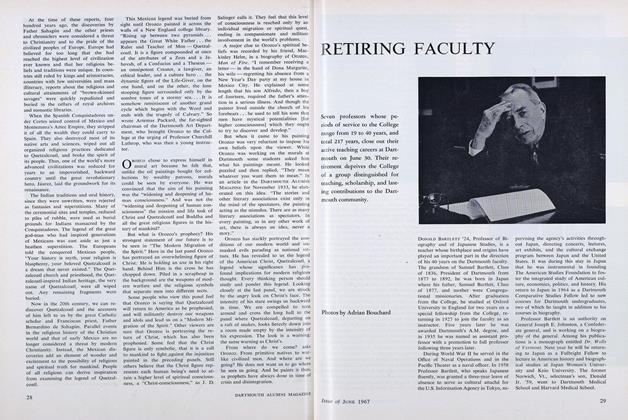

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1967 -

Feature

FeatureAN ATHLETIC SUMMING UP

June 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

June 1967 By RICHARD G. JAEGER, JAMES W. WOOSTER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1967 By ART HAUPT '67

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

June 1917 -

Books

BooksShelflife

May/June 2013 -

BOOKS

BOOKSSomething Fishy

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 -

Books

BooksTHE STAGE MANAGER'S HANDBOOK.

January 1954 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksCHAUCERIAN ESSAYS.

February 1953 By HEWETTE E. JOYCE -

Books

BooksThe Master of Taliesin

MARCH 1982 By William Morgan '66