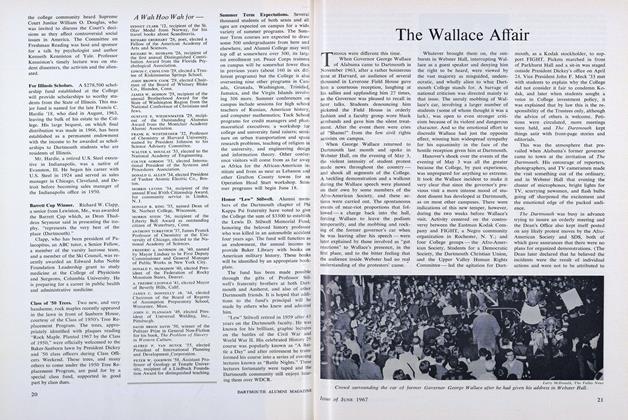

GEORGE WALLACE was a symbol of Southern segregation in 1963, and he was still that symbol in 1967. But in 1963, when the Alabama governor swung through Hanover, he spoke to a large crowd in the Field House while pickets silently paraded outside. What happened this year is history.

Dartmouth students as a whole are not sympathetic to Wallace's political views and action. But the riot of May 3 was appalling - not only because of its severity but because, news media to the contrary, it was instigated by a small number of students, no more than 40, who managed single-handedly to disrupt a public assembly and take events into their own hands.

Some 1200 students were assembled in Webster Hall. An estimated seven students led the loud heckling that greeted Wallace when he arrived on stage, and prevented him from speaking for almost five minutes. A chant of "Wallace is a racist" caught on in the crowded hall for a minute, but the audience then shut up to hear the man out. The hecklers did not.

They were mainly Negro students, who said later that "demonstration was a gut reaction" against Wallace's presence. By letting Wallace speak without protest, they felt, the College would be giving tacit consent to Wallace's views, and allowing him to make political hay as well. Consequently, they began to smear the whole evening.

They stood up shouting invective for a time, until the audience began to shout back, "Throw them out!" Whereupon they staged a walkout.

Reinforced by another ten students, and led by the famous Colby Jr. instructor, the protesters returned and, bowling over hapless student ushers, rushed the podium with the cry, "Would you let Hitler speak?"

The charge was stopped just short of Wallace, and they were escorted out. Wallace resumed his speech, smiling genially, and answered written questions from the audience. Then, after polite applause, he and his entourage (followed by a small army of newsmen, cameras, and lights) went outside to the cars, where the expelled demonstrators were waiting. The car-rocking, shoving, banging, chanting spectacle followed shortly thereafter.

According to an informed eyewitness, no more than 40 students were active in the riot; it was they who pounded and jumped on Wallace's car. This was no jolly watertight - they were very angry. Others chanted anti-Wallace slogans. But out of the crowd of 500 or so, more than 400 were simply onlookers who did nothing.

There was shoving, and damage to the car, but no real violence. The police were only concerned with getting the ex-Governor out. There were no arrests. The riot, from all appearances, was entirely spontaneous, and drew on latent anti-Wallace support, and the lack of any resistance.

In the aftermath, the whole campus spent some time taking stock. The main reaction was shock: "I'm really ashamed," said one student. "I never thought anything like this could happen at Dartmouth." Others expressed surprise or indifference. Some of the original rioters were unrepentant, maintaining that to have let Wallace speak would have been worse. But it was evident that an upper limit on activism had been reached - that it takes no brains, no ideas, no virtuous cause to disrupt a public assembly. All it takes is a strong arm and a loud mouth. As The Dartmouth said, the riot "exposed a venomous side of the Dartmouth student community we never thought existed." And all the students know now what the First Amendment was drafted to prevent.

The next few days Dartmouth spent reading its press clippings and fan mail. Walter Cronkite showed bumpy newsreels, Eric Severeid slapped the student body's collective wrist. Well over a hundred incensed letters, mainly from alumni, arrived at The Dartmouth office, mainly based on inflated newspaper and magazine reports ("Club-swinging police" - US News and World Report; "1000 angry students"— WashingtonPost). But by the time the ManchesterUnion-Leader came out with a page-one editorial ("... the administrations and trustees of American colleges have got to stand up and be counted ...") as far as students were concerned, the affair had blown itself out, at least until the Faculty Committee on Administration could finish its investigation. It was Green Key.

The weather was sunny and cold this year for Key. The second annual Chariot Races were held on the green Saturday, where a cast of thousands watched the wheeling fraternity flagships trundle gloriously around the track, pulled by puffing, pot-bellied brothers. Flags, capes, and bugles were the decorations, combat during the races filled the air with eggs, flour bombs and vegetables, and by the end of the final heat, most of the chariots - everything from an ox-cart to a juke box on wheels - lay in shambles. Beta Theta Pi won the race, Kappa Kappa Kappa won Hums, and Sunday night it snowed and sleeted.

ENVOI: For the past year this writer has happily reported the Hanover scene in an attempt to discern what was really happening (as opposed to what the headlines say), and what the state of the Dartmouth Man c. 1967 was (as opposed to what he is supposed to be). Since the Dartmouth Man is beyond comprehension, I haven't succeeded (time to drop the mask; this has been a prejudiced column anyway), but I've had a lot of fun trying.

Dartmouth is no longer a rural college reportedly some students make liquor runs to Paris and back. The academic standards have gone up, and students have become much more professional in their attitude. They work, they roadtrip all over New England, and they represent a much more diverse America than ever before. The epic rakishness and Babylonian Winter Carnivals of pre-trimester Dartmouth exist only as legends.

"Parkhurst" is, of course, the perennial bogeyman. Student complaints center around coeducation (a good percentage want at least a sister school), comprehensive exams (a good percentage don't want them) and a vague feeling of alienation ("Your learning here is business"). "Creeping weenyism" continues apace. The Wigwam and Choate dorms are still echo chambers. The weather is still lousy. And, one by one, the old gut courses ("Cowboys and Indians" - History 37; "Stars" - Astronomy 1 taught by Prof. Dimitroff) have expired.

On the other hand, the pass-fail option has done much to reduce the pressure, Thayer Hall's unlimited seconds policy, plus such succulent delicacies as fried shrimp and rare roast beef, have silenced the more sardonic criticism; ultimately, the College intends to feed the entire student body.

The extension of parietals to 2 a.m. on weekends and 11 p.m. on weekdays has satisfied most demands - the problem, as always, is getting the girls to come up to Hanover.

During my four years in Hanover I have learned what culture is (Anthropology 1), that Dickens is a heavyweight novelist (English 1), how to create a balance-of-payments crisis (Economics 1), how not to write a short story (English 20), Adolf Hitler's success story (History 32), how to run a successful horror-movie theater (Arthur Mayer's fine film course, in English 84), and 57 incontrovertible theories explaining history (History 86).

My main disappointment is never learning how to fly-cast, or to tap a keg. Nonetheless, the experiences which taught me the most at Dartmouth were not part of the curriculum. One was The Dartmouth, where I spent three years chained to a typewriter, and one year, as reviews editor, chaining others, in the glorious bedlam of Robinson Hall.

Another was Dartmouth Project Mexico in Mexico City, where, two summers ago, a gang of us worked at a Mexican social center and lived with Mexican families. This was an incredible education: the fine people, the ditch-digging, the jet-set life, the poverty of the real world, the snows of Popocatepetl volcano. This Project was one of the high points of my Dartmouth career. I hope I put something back in, and that the lessons I learned in that kaleidoscope of a city will stick.

Then there was Baker Library, and Dean Seymour, and the Film Society flicks in Spaulding, and the Theater-of-the-Absurd weather. Above all, there were the students. We talked, drank, and roadtripped; shot pool, broke legs, and discovered awe-inspiring blue-eyed blondes from Boston. We did everything (Typist: insert Youth by Conrad). Whatever else may happen to the Class of '67 (and everything will), in the last four years of talk and kegs and roadtrips and friendships, we were in all our glory.

On June 11, everyone moves up a notch, the bright, scrubbed '71s get ready to move in, and we are Out of Here, for the last time. Nobody believes in Utopias anymore; no student would say "I had a blast winter term." But Dartmouth - a collection of architecture, elms, books, slush, academics, and IBM cards - comes fairly close. We did have a blast, on balance, and we wish it well.

Duncan, Jack, Hugh (who is marrying a Mexican girl from the Project), Mike, Bill, Babo - all of us are scattering to various destinies — law school, the service, the Peace Corps, and onward to 1974, 1981, 1999, and the 21st century. How long we will remain in all our glory is an open question, but it will be interesting to see how we all make out.

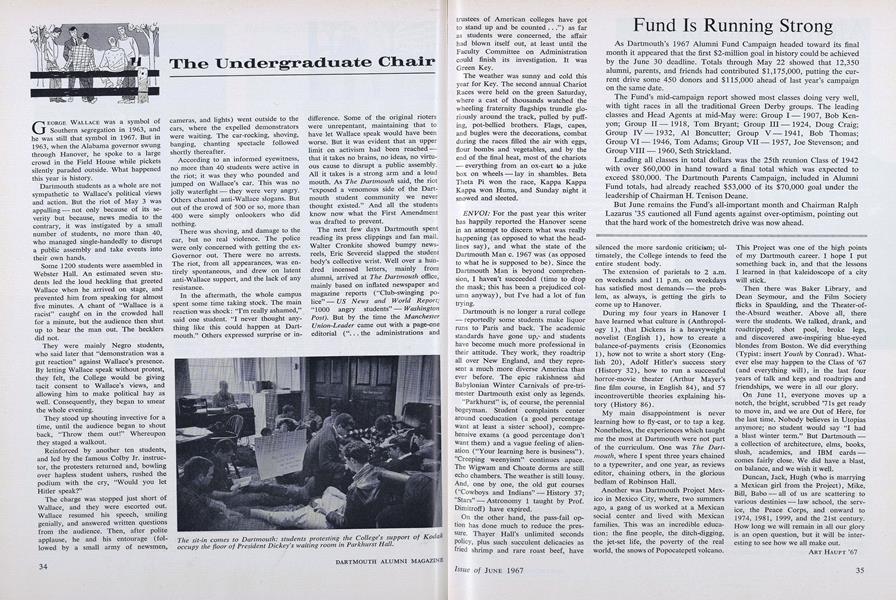

The sit-in comes to Dartmouth: students protesting the College's support of Kodakoccupy the floor of President Dickey's waiting room in Parkhurst Hall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

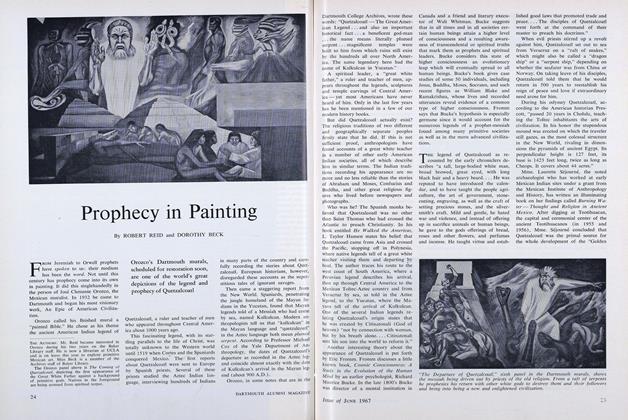

FeatureProphecy in Painting

June 1967 By ROBERT REID and DOROTHY BECK -

Feature

FeatureThe Wallace Affair

June 1967 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1967 -

Feature

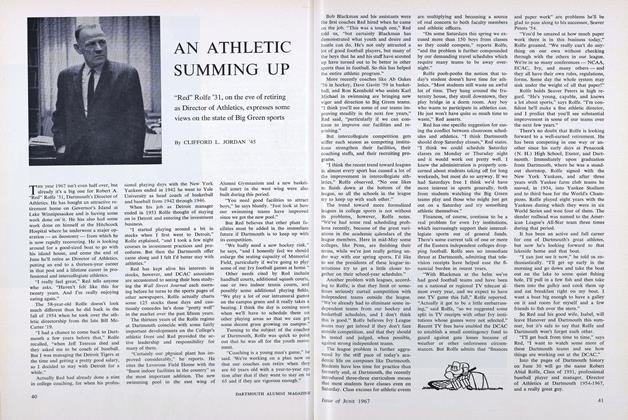

FeatureAN ATHLETIC SUMMING UP

June 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

June 1967 By RICHARD G. JAEGER, JAMES W. WOOSTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

June 1967 By ROGER F. EVANS, H. BURTON LOWE

ART HAUPT '67

-

Article

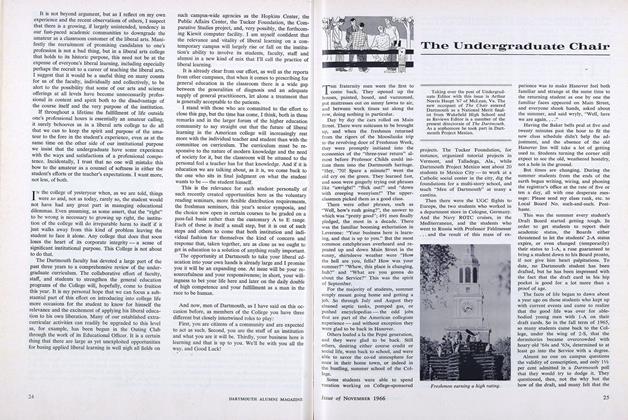

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

NOVEMBER 1966 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

DECEMBER 1966 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JANUARY 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

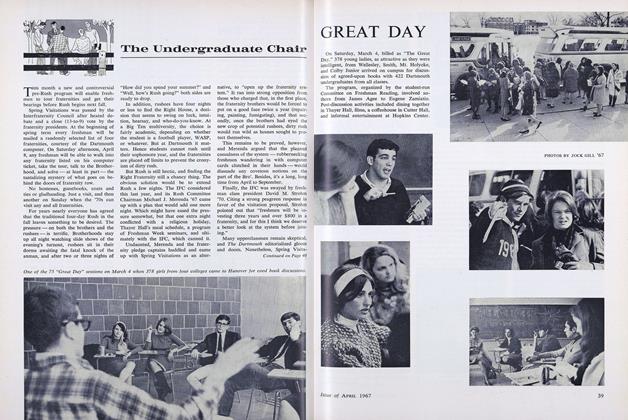

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

APRIL 1967 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1967 By ART HAUPT '67

Article

-

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN BASKETBALL

February, 1914 -

Article

ArticleVeterans as Students

November 1946 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

Nov/Dec 2008 By BONNIE BARBER -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

March 1946 By PARKER MERROW '25. -

Article

ArticleCause for Applause

Mar/Apr 2003 By Roxanne Khamsi '02 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

NOVEMBER 1986 By Willem Lange