Presidential Election Poses the Question Whether Traditional Political Parties Are in the Process of Being Changed into New Voting Coalitions

SORTING out political year 1968 is a difficult and painful enterprise. Too much passion was part of this year to make the task easy or pleasant. Questions were raised about the stability of the nation as well as of the political coalitions that have dominated our politics for 35 years, and questions were raised about the ability of any elected candidate to govern. It is now probably true that the stability of the present coalitions is directly related to the ability of President-elect Nixon to govern effectively.

Traditionally the American citizen has voted what he perceived to be his pocketbook. This phenomenon lies at the heart of the coalition that Franklin Roosevelt put together in the 1930's and largely survives today. In this year's election, however, it failed to achieve the highest office - the Presidency. The obvious question has been raised whether that coalition is finished as a factor in American politics. Have we reached a watershed in the way we group together to elect our officials?

In seeking an answer to that question it is necessary first to look at the initial premise - the politics of the pocketbook. In fact, this is an election in which the pocketbook ceased to be the sole dominant focus of voting. The problems in our cities and the war in Vietnam generated a new focus, the politics of conscience. The counter-reaction produced the politics of fear. Each of these new foci produced their candidates. The politics of conscience found spokesmen in Senators McCarthy and Kennedy, and the politics of fear found Wallace and LeMay. The major parties stuck to the traditional concerns and nominated Humphrey and Nixon. Those concerned with conscience or fear found this choice like the proverbial difference between tweedledumb and tweedledumber, a major source for the lack of enthusiasm in this election.

The significant aspect of this election was the fact that more Democrats became infected with the politics of conscience and fear than did Republicans. The nominal Democratic majority disappeared; Nixon was elected President with 43 percent of the vote, albeit 2 points more than Wilson's 1912 victory. Who was elected may not be as important, however, as his ability to govern. President Johnson was forced out of the race when it became apparent that although he could probably win he could probably not govern. What does this election mean in terms of the problem of governing?

The Roosevelt coalition was based on solid support in the South combined with labor and liberal backing. Humphrey lost the deep South to Wallace, the border states to Nixon, some of labor to Wallace, and some of the liberal faction to handsitting. The politics of conscience and fear eroded votes that Humphrey normally could have counted upon. These developments have split groups which have always cooperated but been potentially antagonistic: the Southerner, the bluecollar worker, the Black man, and the liberal. These groups could agree on pocketbook issues but the increased salience of the issues of conscience and fear proved too much. Conscience and fear, moreover, are exactly the factors that make governing difficult.

Nixon's coalition was basically the old Republican formula, this time aided by a third party and a badly split Democratic party. Nixon's mainstreet aggregation seeks a less volatile politics at a volatile time. As a coalition it is not stable and is vulnerable to a united Democratic party under, say, the banner of Kennedy or Muskie in 1972. Nixon to win, then, must find a way of expanding his coalition.

In this task he has the advantage of projecting a conservative image with the real possibility of de-fusing the right and undercutting the politics of fear. This would not only benefit him politically but aid the nation in cooling down one sector in a badly overheated polity. To broaden his coalition in the other direction, the Nixon administration must be able to start progress in dealing with the fundamental imbalances in our society. The issues that have been on the back burner for so long must be tackled. While he might be able to de-fuse fear, he must deal with conscience. The first issue here will be the rapid and complete termination of the Vietnam war.

Humphrey's narrow loss can be attributed less to the breakup of a majority coalition than to the fact that bossism doesn't look good on television. His decline in popularity in August would normally have reversed after the Democratic convention. The spectacle of Chicago's Mayor Daley, his police, and intemperate youth made Humphrey's task almost impossible. That debacle did not add to the Presidential image of HHH.

The Democratic party could seek the route of restoring its power in the deep South and among the most conservative elements in the union moyement or it could seek to build a winning majority or plurality out of the liberal vote plus the minority vote. Something like 35 to 40 percent of white voters can be judged liberal, representing those who disapproved of police behavior in Chicago and those who think that not enough has been done for minority groups. It is probable that enough" others would vote out of party loyalty or for a change to allow the second alternative to succeed. To seek the conservative alternative would indeed destroy the Roosevelt coalition.

George Wallace appealed to the worst in the American electorate: fear. Paranoic fear of communism, Black men, and the complexity of modern life led many to the simplistic, ill-considered, and intemperate rhetoric of Wallace and his running mate, LeMay. When Wallace used phrases such as "we should turn the country over to the police for a couple of years," he was making what in another era would have been called a fascist appeal. In this light it is disturbing to find such a number of people in this country who could be duped by some future Hitler. Over 13 percent of the people nationally voted for the politics of fear. This is manyfold the number voting for parties on the far left, an indication of what may be the significant potential extremism of the future.

Nixon won, then, through a weakening of old coalitions, not through their demise. The year 1972 will determine whether there will be a new pattern of voting or a slight modification of the present. If Nixon fails in the task of governing, he will be vulnerable to a revitalized Roosevelt coalition. If he succeeds, he could build a new majority party. He must come up with a reformulation of Republican pocketbook issues so as to reduce the appeal to conscience and fear, as well as broadening Republican constituents.

THE termination of the Vietnam war will have to be used to reduce defense spending to something like $55 billion in order to free resources to deal with domestic problems. President Eisenhower's last warning on the power of the defense community has proved prophetic and it will take tremendous courage and careful use of power to stand up to the generals, admirals, and their civilian counterparts. It does not appear beyond speculation that the military would relish a $100 billion budget — a figure, incidentally, equal to the proposed Freedom Budget for our cities suggested by A. Philip Randolf in 1964 and laughed at as unrealistic. The military could well become the Achilles heel of the Nixon administration if he persists in the rejection of nuclear parity. The Republican elephant could become the proverbial mouse built to military specifications. One hopes the sophomoric military analysis used in the campaign was for that purpose only.

The costs of the Vietnam war are not hard to calculate. On optimistic projections it will have direct costs in the neighborhood of $100 billion, an equal amount for future veterans' costs, debt amortization, and military stock replenishment. Promotion, hiring, and resignations in the civil service and military have been biased by those who have been all out for the war and have developed a bureaucracy of a more uniform perspective. In addition, the sentiment for limiting our foreign involvement has extended to the development loan field as well. This world cannot continue peaceably with a few rich and most desperately poor. Had the hundreds of billions spent for Vietnam been used constructively both domestically and abroad, much of the rancor and divisiveness of the present campaign might have been avoided. The Vietnam war hardly represents rational allocation of resources.

This huge expenditure has prevented the nation from dealing with the problems of our cities. Nevertheless, the Black community voted almost unanimously against Mr. Nixon. It is possible that only by picking up the themes of the Kerner Report, ignored by its sponsor, can the next administration hope to attack the vestiges of white racism to forestall Black racism. Several hopeful notes were sounded in the campaign on this subject. Milton Freidman's suggestion of a negative income tax to eliminate the oppressive and dehumanizing welfare system, the idea of selling public housing to residents as cooperatives to foster the pride of private ownership, and the development of low-interest, long-term loans to Black entrepreneurs to provide an opportunity are the sort of program that can lead to the development of effective cooperative action with constructive militants. It is possible that the Nixon administration can do more than any other because it is not tied to an uptight union vote or the deep South. There is a compelling conservative argument for many of these programs which the next administration can use if it has the will.

Two terrible assassinations, violence in our cities, violence on our campuses, dramatic shifts in political fortune, much stale as well as intemperate political rhetoric, and an ill-conceived war have all led to a badly overheated polity. It is a situation in which the youth of the nation are sorely confused about the nature and proper functioning of authority. While there are incidents to bolster an argument that youth are irresponsible, there is a greater wealth of information to indicate that never has this country been blessed with such a sophisticated, concerned, and intelligent group of younger people. That they are not accepting blindly but are critically examining the behavior of their elders, that they find something wanting, should not reflect ill on them. They are asking most fundamentally that authority be commanded not merely demanded. They want to respect but insist that respect be warranted.

The concerns of youth illustrate the problems facing the new administration and will determine its success in 1972. Some in positions of authority have focused their attention on things like even well-groomed long hair, and other trivia, thus undercutting respect for all authority. The new administration must be sensitive to the criticisms of youth or risk failure in 1972. A factor in this sensitivity which I would like to see restored is a sense of humor. While these are by no means humorous times, if we lose the capacity to laugh at ourselves once in a while we shall be even more unhappy politically than we are now.

These musings present a somewhat cautiously optimistic projection of the ability of the American political parties to deal with the problems facing us in 1969. The question of governing is not constrained by structure, institutions or personalities; it is only limited by will. In conclusion, it should be understood that these remarks are the product of the leisure of the theory class, and that reality probably looks different from the Hotel Pierre.

The Author: Edward W. Gude '59 is Instructor in Government at the College. As an undergraduate, he served as president of The Dartmouth and chairman of Palaeopitus and received a Senior Fellowship for independent study. After graduation, he studied at the London School of Economics, 1959-60, on a James B. Reynolds Scholarship and at M.I.T. from 1960 to 1962 under a National Defense Education Act Fellowship. He is now completing M.I.T.'s requirements for a Ph.D. in political science with a specialty in "violence and conflict." He joined the faculty at Dartmouth this fall after three years at The American University in Washington and two years as instructor at Northwestern University. In addition to the introductory course in Government, he is teaching the course in 'American Parties and Politics."

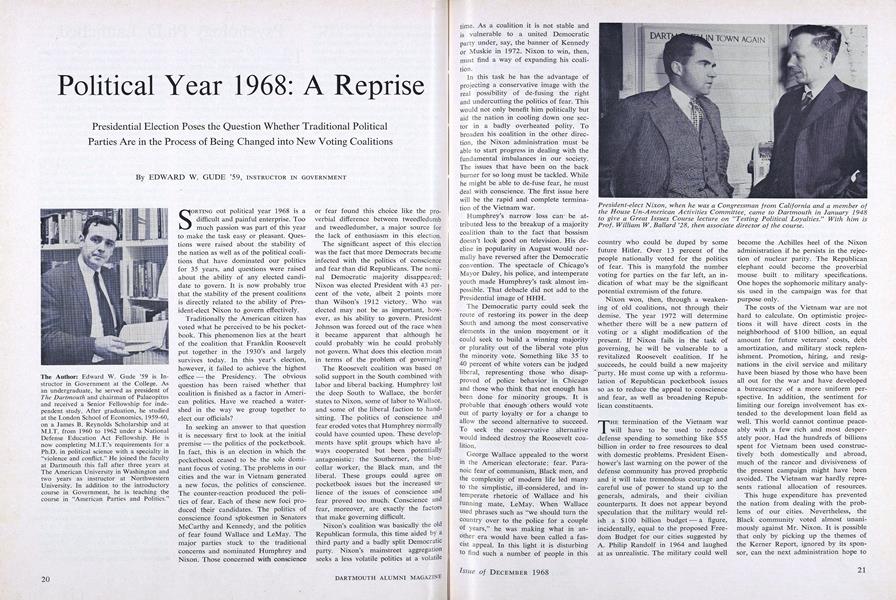

President-elect Nixon, when he was a Congressman from California and a member ofthe House Un-American Activities Committee, came to Dartmouth in January 1948to give a Great Issues Course lecture on "Testing Political Loyalties." With him isProf. William W. Ballard '28, then associate director of the course.

In connection with the 1968 Presidentialelection, display cases in Hopkins Centerwere filled with buttons and stickers fromprevious campaigns.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Our trusty and well-beloved John Wentworth Esq., Governor"

December 1968 By Susan Liddicoat -

Feature

FeatureOf Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas

December 1968 By DEAN THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

December 1968 By STANLEY H. SILVERMAN, EDWARD S. BROWN JR. -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

December 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1968 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

December 1968 By THOMAS J. SWARTZ JR., HERMAN E. MULLER JR.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT

July 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThe Purpose Gap

MARCH 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHALDEN CALCULEX CIRCULAR SLIDE RULE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

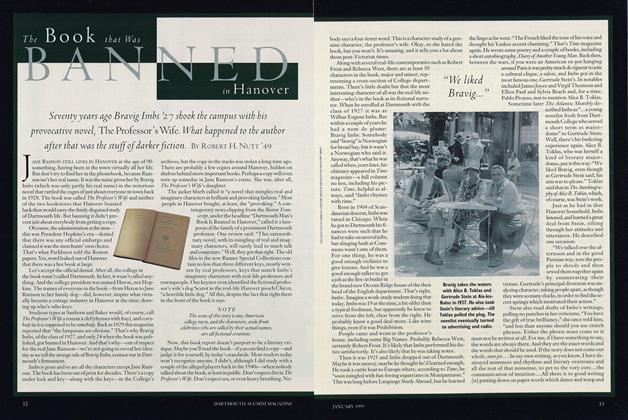

FeatureThe Book That Was Banned in Hanover

JANUARY 1999 By Robert H. Nutt '49 -

Feature

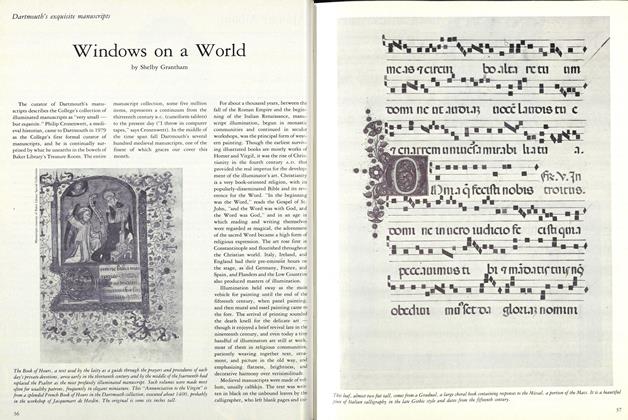

FeatureWindows on a World

DECEMBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

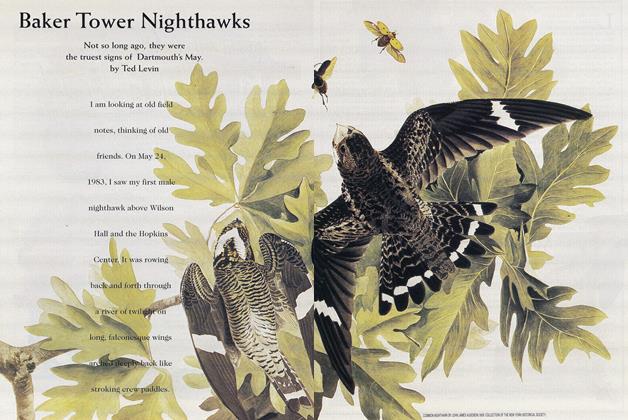

FeatureBaker Tower Nighthawks

May 1994 By Ted Levin