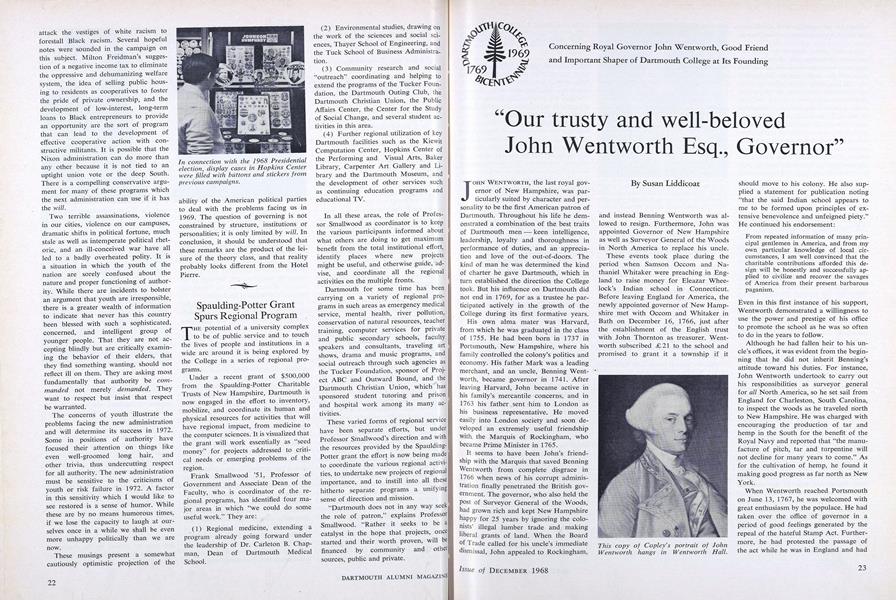

Concerning Royal Governor John Wentworth, Good Friend and Important Shaper of Dartmouth College at Its Founding

JOHN WENTWORTH, the last royal governor of New Hampshire, was particularly suited by character and personality to be the first American patron of Dartmouth. Throughout his life he demonstrated a combination of the best traits of Dartmouth men - keen intelligence, leadership, loyalty and thoroughness in performance of duties, and an appreciation and love of the out-of-doors. The kind of man he was determined the kind of charter he gave Dartmouth, which in turn established the direction the College took. But his influence on Dartmouth did not end in 1769, for as a trustee he participated actively in the growth of the College during its first formative years.

His own alma mater was Harvard, from which he was graduated in the class of 1755. He had been born in 1737 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where his family controlled the colony's politics and economy. His father Mark was a leading merchant, and an uncle, Benning Wentworth, became governor in 1741. After leaving Harvard, John became active in his family's mercantile concerns, and in 1763 his father sent him to London as his business representative. He moved easily into London society and soon developed an extremely useful friendship with the Marquis of Rockingham, who became Prime Minister in 1765.

It seems to have been John's friendship with the Marquis that saved Benning Wentworth from complete disgrace in 1766 when news of his corrupt administration finally penetrated the British government. The governor, who also held the post of Surveyor General of the Woods, had grown rich and kept New Hampshire happy for 25 years by ignoring the colonists' illegal lumber trade and making liberal grants of land. When the Board of Trade called for his uncle's immediate dismissal, John appealed to Rockingham, and instead Benning Wentworth was allowed to resign. Furthermore, John was appointed Governor of New Hampshire as well as Surveyor General of the Woods in North America to replace his uncle.

These events took place during the period when Samson Occom and Nathaniel Whitaker were preaching in England to raise money for Eleazar Wheelock's Indian school in Connecticut. Before leaving England for America, the newly appointed governor of New Hampshire met with Occom and Whitaker in Bath on December 16, 1766, just after the establishment of the English trust with John Thornton as treasurer. Wentworth subscribed £21 to the school and promised to grant it a township if it should move to his colony. He also supplied a statement for publication noting "that the said Indian school appears to me to be formed upon principles of extensive benevolence and unfeigned piety." He continued his endorsement:

From repeated information of many principal gentlemen in America, and from my own particular knowledge of local circumstances, I am well convinced that the charitable contributions afforded this design will be honestly and successfully applied to civilize and recover the savages of America from their present barbarous paganism.

Even in this first instance of his support, Wentworth demonstrated a willingness to use the power and prestige of his office to promote the school as he was so often to do in the years to follow.

Although he had fallen heir to his uncle's offices, it was evident from the beginning that he did not inherit Benning's attitude toward his duties. For instance, John Wentworth undertook to carry out his responsibilities as surveyor general for all North America, so he set sail from England for Charleston, South Carolina, to inspect the woods as he traveled north to New Hampshire. He was charged with encouraging the production of tar and hemp in the South for the benefit of the Royal Navy and reported that "the manufacture of pitch, tar and turpentine will not decline for many years to come." As for the cultivation of hemp, he found it making good progress as far north as New York.

When Wentworth reached Portsmouth on June 13, 1767, he was welcomed with great enthusiasm by the populace. He had taken over the office of governor in a period of good feelings generated by the repeal of the hateful Stamp Act. Furthermore, he had protested the passage of the act while he was in England and had worked for its repeal, both of which contributed to his popularity in New Hampshire.

In such troubled times as the years immediately preceding the Revolutionary War, any royal governor needed all the good will he could muster. Wentworth was able to maintain the people's approval by consistently developing and promoting policies that contributed to the development of his native province. Throughout his term, in his dealings with the Assembly of the colony and the people in general, he was very skillful in the exercise of personal diplomacy. He took care to give the revolutionary zealots no excuse to drive a wedge between himself, the representative of the Crown, and the people of New Hampshire. And he succeeded in keeping his colony from becoming involved in rebellious acts against England longer than any other royal governor in America.

As governor, Wentworth considered the promotion of education in New Hampshire to be one of his responsibilities, and his colony was without a college. With that in mind, six months after he took office, Wentworth arranged an interview with Eleazar Wheelock in Portsmouth to discuss moving his Indian school from Lebanon, Connecticut, to New Hampshire. As some of the proposed locations in other colonies began to look less attractive to Wheelock, he had decided to investigate New Hampshire's prospects. Following the meeting with Wheelock, John Wentworth spelled out more specifically the offer of a township he had made while in England:

I shall be ready to grant a township on Connecticut River of six miles square for an endowment of the school and as a site to fix it upon where there may be room, and advantage of soil and water, to practice, teach, and accommodate the necessary studies of agriculture.

Wentworth went on to set forth the terms of the grant. (1) The school would have to pay only a moderate quitrent (annual fee) to the king. (2) Eighty to a hundred people must be settled on the land within five years of the grant. (3) The mines on the land were to be reserved for the king. (4) The school would actually have to be established in New Hampshire; that is, the proceeds from the land could not be used to support the school in another colony. (5) The governor of New Hampshire must be a trustee of the school "to the end that His Most Sacred Majesty and his successors may be always informed of and satisfied with the just and prudent application of their royal bounty."

In establishing all those conditions, Wentworth was reflecting his twin responsibilities — to his king and to the people of his colony. Indeed, he stated that he desired to help the Indian school not only because it was "founded on the most benevolent and exalted principles of Christian Piety," but also because it was

calculated with great certainty to produce the political advancement of his Majesty's Colonies, by reclaiming a numerous people [the Indians] from their savage, desultory enmity; to an orderly, peaceable and happy subjection to the Laws. . . .

After stating the terms of his grant, Wentworth listed the attractions of New Hampshire that made it a desirable location for the school:

the extensive water communication, rich soil, healthy climate, rapid population, inconsiderable taxes, freedom from public debt, commercial markets for produce, and above all the unexampled tranquillity, harmony, and unison of our government.

He closed with a final pledge of "every personal assistance in my power," and promised to forgo the usual fee paid to the governor by the recipient of a grant.

In his efforts to persuade Wheelock to move to New Hampshire, Wentworth was supported by the settlers on the Connecticut River. Many of them had recently moved from Connecticut, and they were well acquainted with Wheelock and with the school. Having received the promise of further offers of assistance from private citizens in New Hampshire, Wheelock wrote to the English trust suggesting that the school be moved to that province, and they accepted his recommendation.

With the general location of the school settled, Wheelock began negotiating with Governor Wentworth for a charter in August 1769. Throughout the negotiations the governor showed himself to be open-minded and interested in the welfare of the new college. For instance, he was quick to adopt Wheelock's modest suggestion that the institution be called a college rather than an academy.

Had Wentworth been more difficult to bargain with, the new institution might have borne his name. Wheelock had instructed his son-in-law and chief negotator, Alexander Phelps, to suggest naming the college after Wentworth if necessary to gain his good will. However, Wheelock preferred to accord Lord Dartmouth that honor.

My obligations in point of Gratitude to the Earl of Dartmouth are great, and I conceived that some advantage on that side of the Water might accrue by manifesting my desire to do him honour in this way. But if it be tho't it may bear his Excellency's [Wentworth's] Name to better advantage, and give no disgust to my Patrons at home, I will submit the matter to You. . . .

Wheelock had already invited the governor to "christian [sic] the House to be built after Your own Name," and he concluded his instructions to Phelps: "Perhaps the name of the House will be as agreeable to the Governor as the Name of the College." Apparently it was.

In general it seems that Wentworth's attachment to the Church of England pitted against Wheelock's dissenting religious views produced a charter remarkable in its day for its absence of narrow religious restrictions. The twelve-member board of trustees was never to have more than five clergymen. Furthermore, the trustees were not to exclude, in the words of the charter,

any Person of any religious denomination whatsoever from free and equal liberty and advantage of Education or from any of the liberties and privileges or immunities of the said College on account of his or their speculative sentiments in Religion and of his or their being of a religious profession different from the said Trustees of the said Dartmouth College.

Wentworth was practical enough to know that in a colony largely populated by dissenters, he couldn't hope to turn Dartmouth into an Anglican college. But he could make sure that it was not used to promote the exclusive interests of the dissenters.

Another area of contention between Wentworth and Wheelock was the former's desire to have three provincial officials from New Hampshire, as well as himself, serve as members of the board of trustees. Wheelock had already agreed to have the governor as an ex officio member of the board, but he wanted the rest of the trustees to be his Connecticut friends who had long been supporters of the Indian school. Persuasively Wentworth pointed out that while he did not insist on adding the provincial officials to the board, he thought the new college would benefit from "such an honorable Patronage" and from being able to list them as trustees. He reiterated his pledge "at all times [to] seek the welfare of the College."

As finally stated in the charter, eight of the twelve trustees were to come from New Hampshire; however, originally there were only five: the governor, the president and two other members of the Governor's Council, and the Speaker of the House. Although Wheelock at first had his majority of Connecticut trustees, difficult traveling conditions often prevented their attending meetings, and it soon became evident that they would have to be replaced by trustees living closer to the College.

Under the charter, the trustees had broad powers to appoint officers of the College, provide for instruction, and award any degrees "as are usually granted in either of the Universities or any other College in our Realm of Great Britain." Wheelock was appointed the first President, and he could name his successor, but thereafter the board would elect the President. They were also to fill any vacancies in their own body. According to negotiator Phelps, the charter was judged to be "the most Generous of any on the Continent."

Two important events in Wentworth's personal life took place during the fall of 1769 while negotiations for the Dartmouth charter were in progress. John Singleton Copley, the most famous portrait painter of the day, arrived "to take my picture,"- as Wentworth wrote a friend. Then on October 28, 1769, Portsmouth was saddened by the death of the secretary of the colony and a cousin of the governor, Theodore Atkinson Jr., at the age of 33. Only two weeks later, as reported in the Boston News-Letter of November 17, 1769, the mood of Portsmouth changed to one of "Mirth" and "Joy . . . smiling in every Countenance on this happy Occasion" as the "Governor was married ... to Mrs. Atkinson, Relict of the Hon. Theodore Atkinson, jun. Esq.; deceased." Judging from the portrait of Frances Atkinson painted by Copley in 1765, it is easy to see why the bachelor governor wasted no time in marrying the young widow of 24 who was also his cousin. And thus it was a husband of one month who granted the "generous" charter to Dartmouth on December 13, 1769.

The next college matter that concerned Wentworth and Wheelock was the selection of an exact location for Dartmouth on the Connecticut River. All the towns along the river tried to outbid each other in their offers of land. Dartmouth's trust fund of £10,000 made it quite a prize for any town in 1770. Wherever the college might be situated, it was felt that the surrounding land would greatly increase in value. As the bidding increased, Governor Wentworth became concerned over the speculation in land that was ensuing. He concluded that he should not agree to situating the College in any town where most of the land

lay in a few Men's Hands,. . . [although] he owned a great part of several Towns himself, and it would greatly raise the Value of his Property to have the College fixed in one of those Towns, but... he was not consulting his own Interest, but the declared design of the Institution.

He had already granted the township of Landaff to the College, and he thought it should be located there. Then the College, rather than any land speculators, would benefit from the increase in land value.

At this point, Wheelock felt it would be wisest to postpone any decision until the spring of 1770. After inspecting various prospective sites along the Connecticut River, including locations in Hanover, Lyme, Orford, and Haverhill, Wheelock proceeded to Plymouth and finally to 'Portsmouth to meet with the governor. There on July 5, 1770, he was able to persuade Wentworth and the New Hampshire trustees to accept Hanover as the location of the College. It seems that Wheelock chose Hanover because the land offered there was all in one large block of 3,300 acres, whereas in the other towns the lots to be granted were scattered. He opposed locating Dartmouth in Landaff, which remained in the College's possession, because the site wasn't on the river. It is to Wentworth's credit that although he had strongly supported Landaff, he now energetically defended the selection of Hanover in the face of accusations of dishonest dealing made by the disappointed towns and landowners.

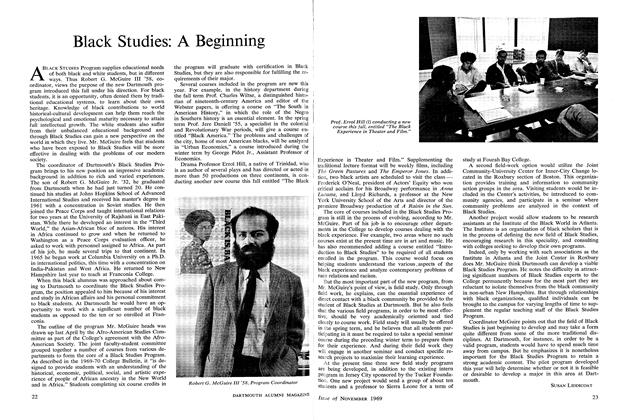

That was only one instance of Wentworth's efforts to defend and promote Dartmouth. During the next five years as governor, he functioned as a one-man public-relations firm for the College in Portsmouth. He dignified the first commencement in Hanover on August 28, 1771, with his presence, and brought with him sixty gentlemen from Portsmouth in an effort to arouse their interest in Dartmouth. He even contributed the refreshments for the occasion - a whole ox that was roasted on the green and a barrel of rum. As a memento of their visit, the governor and his party later presented Wheelock with the now-famous silver punch bowl. In 1772 and 1773, Wentworth again traveled to Dartmouth commencements and continued his practice of bringing a number of friends with him "in great hopes to interest their hearts where their duty has long since called them, and thereby obtain a proper support for Dartmouth College, already too long delay'd."

The governor had felt that Dartmouth, as the only college in the colony, would receive financial support from the Assembly as well as from prominent men in the colony, but neither source contributed very much despite his constant urgings. Perhaps the hard feelings generated at the time the exact site of the College was chosen could not be overcome. In 1770 the Assembly ignored his appeal in behalf of Dartmouth, and this lack of response prompted him to write: "Does it not prove the necessity of a College in a country where Legislators will not grant an encouragement to Literature?" Then in 1771 only £60 were voted for Wheelock's support. In June 1772, Wentworth reported to Wheelock:

The Assembly wou'd not consider either of the memorials presented in behalf of the College; They were laid over to the next session, which I believe will turn out advantageously, as many of the Members are ashamed that so little has been done. Avarice is the Rock that keeps this Province down. Dartmouth College feels its weight in this instance.

Finally in 1773 he suggested that-the trustees of the College hold a special meeting in Portsmouth when the Assembly was in session, which they did. They presented a petition to the Assembly on May 27 "that a new College building is of absolute necessity to accommodate the numerous students applying for an education," and received a grant of £500 the same day. But that was the last time the College received any financial support from the colonial Assembly.

BESIDES soliciting money from the Assembly, the governor sought to aid the College (and make his trips to commencement a little easier) by including a road to Hanover in his overall road-making plans for the colony. In those days, rivers usually served as the highways of commerce, and Wentworth knew that the main rivers of New Hampshire directed the colony's trade toward the ports of Boston, Newburyport, or New Haven. With the dual purpose of redirecting the commerce of New Hampshire to Portsmouth and also uniting the various sections of the colony, Wentworth proposed that the Assembly undertake the building of a system of four major roads. One of these was to run from Wolfeboro, the governor's country home near Lake Winnepesaukee, by way of Moultonboro, Plymouth, Hebron, and over Moose Mountain to Hanover. In explaining his highway plan to the Assembly in 1770, he noted that

the greatest Benefits may Result from Dartmouth College being happily established in the Province, whence many hundred respectable Familys from other Colonies are induced to settle in and cultivate the remotest District of this government, and above all others that the great blessing of Literature may thereby be Disseminated among the People now destitute thereof to a Degree .. . well known. . . .

The Assembly was in agreement with the plan but didn't want to levy a tax to put it into effect. Instead they appropriated a small sum to survey and lay out the line of the new roads and placed the responsibility for actually developing the highways on the proprietors of the townships through which they would run. Since he felt that this scheme might prove to be ineffective, Wentworth decided to use the money he collected as quitrents due the king to accelerate the completion of his road-building project. He also felt that expending the people's fees to improve the colony would help to allay their opposition to paying quitrents. Wentworth reported to England that by this method in 1771 he had been able to make passable two hundred miles of roads "from the western limits of the province to the seacoast, in parallel directions." But from all indications the road to Hanover was never entirely completed, and the governor's annual journeys to commencement remained a major undertaking, especially the climb on horseback over Moose Mountain.

Wentworth, however, seemed to revel in arduous expeditions into the less settled parts of his province. In a letter to a friend in 1770 his wife Frances explained that her husband was "so resolute" he "would attempt, and effect if possible, to ride over the tops of the trees on Moose Mountain." No doubt his love of the out-of-doors accounted for the enthusiasm with which he carried out his duties as surveyor general. As noted earlier, unlike his predecessors in office, he took his role as protector of the woods seriously and tried to effect a reasonable enforcement of the very restrictive British forest policy. According to the law, no white pine trees were to be cut on either public or private property without the permission of the surveyor general. They were to be reserved for the masts of the Royal Navy and cut only when an order came through from the navy. Enforcement of the law would have prevented a settler from clearing and cultivating his land and using pine boards to build his house. As a result, before John Wentworth's tenure of office, the law had been largely ignored except when his uncle used it to prevent other merchants from cutting in on his family's monopoly of the mast trade with the Royal Navy.

With sound conservation ideas as a basis, John Wentworth decided to develop a working relationship with the woodsmen and sought to impress them with the "Importance as well as the Legality embraced by this Service." He informed them that he would prosecute a man for felling white pine trees that were suitable for masts and had been so marked with the King's "broad arrow," but the cutting of the other pine trees to saw into boards would be ignored. And he proved that he could enforce his amended policy. Much to the woodsmen's surprise, he was willing to travel hundreds of miles even in the winter to apprehend violators of his policy. Then unless he was sure he could win the case, he never instituted any court proceedings against the violators. When the price received at the auction of the seized timber did not meet court costs, he was willing to take the loss in order to make his point that the law would be enforced. His new methods made an impression on the woodsmen, and he was able to report to the Colonial Secretary that

in many places where the name of a Surveyor was odious and detestible and even his person unsafe, I have caus'd these people to Sollicit of me, an Officer to preserve the Timber. . . .

Wentworth coupled his enforcement of forest policy with efforts to survey the tracts of white pine in the northern colonies. He and his three deputies traveled widely through northern New York, western New England, and along the coast of Maine to Nova Scotia. They noted stands of white pine, marked trees suitable for masts with the broad arrow, and established some areas of young trees as reservations out of bounds to woodsmen.

Besides their surveying duties Wentworth gave his deputies the additional charge of recruiting some Indian youths for Dartmouth. In January 1772, Wentworth wrote to Wheelock confidently:

I have a prospect of getting you Six or Eight indians from the Eastern Tribes of Penobscot and St. Johns in the Bay of Fundy. I have instructed my surveying officers now with a vessel stationed 3 months in that district to procure me that number or more; and send them directly here in the vessel. . . .

But then in June of that year, Wentworth had to admit a lack of success to Wheelock, although he was still optimistic about prospects in the future.

The St. John's indians are not yet prevailed on to send any Youth for education: They have promis'd me a Visit this Summer, at this place [Wentworth House in Wolfeboro], upon that business, when I hope to engage them therein; in the mean time my Officers in the Eastern Country persevere in their invitations.

That summer on the other side of the Atlantic, another meeting of importance to Wentworth was taking place. In London Mr. Peter Livius of Portsmouth met with the Board of Trade and lodged a formal complaint against the governor charging him with a number of "illegal and unworthy acts." Wentworth was then invited to send a refutation of the accusations, and the case dragged on for a year. Not until December 1773 did the news reach Portsmouth that there "was no foundation for any censure upon the . . . Governor."

The town celebrated by giving a ball in honor of their governor. To commemorate the occasion, the town of Londonderry sent a tribute to Wentworth and in it noted the importance of the establishment of Dartmouth to the colony:

The cultivation of land within the government, and the extension of settlements even to regions that were scarce known when your Excellency came to the chair, must be attributed in a great measure to your care and the benignity of your government. But it has not been in this view alone that you have been the patron of this people. To extend settlements or to cultivate lands while the people that settle and cultivate are without the means of knowledge, might be rather injurious than beneficial. But these have not escaped your Excellency's attention. The institution of a college in the wilderness, and the liberal encouragement it has received from your hand is abundant evidence of this attention.

Wentworth had gained the confidence of the people of New Hampshire, the tribute went on, by "the unabated attention" he had "given to the interests of the province." Since his ears were always "open to their voice," they were able to make known "all necessary information of their wishes and their wants." Because of the rapport between Wentworth and his people, he was able to persuade them in 1768 not to join the other colonies in the nonimportation agreement that sought repeal of the taxes levied by the Townshend Acts. While continuing to maintain the appropriate official appearance, privately the governor severely criticized the blunt manner in which the new customs commissioners introduced the taxes to the colonists. He believed that any Englishman would have instinctively rebelled when treated in such an authoritarian manner. Nonetheless Wentworth could not condone the violent reactions of the revolutionary mobs on several occasions. Still he wrote to the Marquis of Rockingham, no longer Prime Minister, that stationing British troops in Boston in 1768 would not solve the problem.

Perhaps military power may preserve the subjection of conquests, but I believe . . . the just dependence of the British colonies in this continent can be ascertained only by a wise, moderate, and well-timed reformation and strengthening of their government.

In 1774 Wentworth was able to prevent a repetition of the Boston Tea Party in Portsmouth by a careful handling of the situation when a shipload of tea arrived. But he did not succeed in talking New Hampshire out of sending two delegates to the First Continental Congress that year. For the first time official business prevented his attending the Dartmouth commencement. He wrote his regrets to Wheelock:

I wish it was possible for me to be absent from Portsmouth, I would rejoice to spend two or three days with yo.... Such is the distracted state of the Colonies, that I cannot engage to be at Commencement . . . .

As one revolutionary incident followed another in 1775, the governor expressed his increasing concern over the developing conflict:

Our hemisphere threatens an hurricane. I've in vain strove almost to death to prevent it. If I can bring out of it at last safety to my country and honor to our sovereign, my labors will be joyful, and I yet think I shall. My heart is devoted to it.

But in June the revolutionaries forced Wentworth to seek refuge in Fort William and Mary in the Portsmouth harbor. As commencement time at Dartmouth approached, Wheelock, knowing that again the governor would not be able to attend, voiced his sympathy for the College's loyal friend:

I long to See our dear Governor, I never pittied him as I doe now - his Tryals are many and great - and he has a gang of. .. hot headed Ignorant, unruly Fools to try him.

The Dartmouth commencement would never again be honored by Wentworth's presence.

The governor was safe in the fort only as long as the British frigate Scarborough remained in Portsmouth harbor. When it had to sail to Boston for supplies, Wentworth had no choice but to go aboard with his wife and six-month-old son and leave New Hampshire. He spent the winter in Boston, which was besieged by the Revolutionary Army, with the hope of going back to New Hampshire. Through 1777 he continued to feel that if he could return to his home with an expeditionary force, there would be a great show of loyalty for the Crown. After General Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga, though, he decided in February 1778 he would join his wife and son in London.

Five years later he was on his way back to America, but this time to Nova Scotia. He had been reappointed the King's Surveyor General of North America, only now that domain had been greatly reduced. But this change made the protection of the white pine trees remaining under British control doubly important, and Wentworth enthusiastically resumed his duties.

During a visit to England in 1791, he was appointed lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia. Although technically he served under the governor at Quebec, Wentworth was in fact the chief executive of his province, which then included New Brunswick. As in New Hampshire, he gained the confidence of the people through the concern he showed for their welfare. His interest in education continued, and in 1802 he secured a charter for King's College in Windsor, Nova Scotia. When war between England and France broke out in 1793, he was able to keep the allegiance of his French colonists as well as of the Indians. He certainly merited the baronetcy conferred upon him by the King in June 1793.

Although his interest in New Hampshire continued and he corresponded with friends in the United States, he never revisited his homeland. After he was relieved of his governorship in 1808 because of advancing age, Wentworth and his wife decided to sail to England in 1810 to be with their son. When Lady Wentworth died in 1813, the former governor returned to Nova Scotia, where he lived until his death in 1820 at the age of 83. Eight years later Dartmouth, recalling the important role played by the former governor in the founding of the College and Wheelock's intention at that time, named the new building at the north end of Dartmouth Row for Sir John Wentworth.

To this day, Dartmouth Hall is flanked by companion buildings named for the two great, good friends the College was fortunate to have in its founding period - Thornton Hall for its most generous patron in England and Wentworth Hall for its staunchest friend in colonial America.

This copy of Copley's portrait of JohnWentworth hangs in Wentworth Hall.

Portrait of Mrs. Theodore Atkinson Jr.who as a beautiful young widow of 24married Governor Wentworth one monthbefore Dartmouth's charter was granted.

The Wentworth Bowl, fashioned by Boston silversmith Daniel Henchman, is one ofDartmouth's prized possessions. Although it commemorated the first Commencementin 1771, it was not actually given to Eleazar Wheelock until March 1773.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOf Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas

December 1968 By DEAN THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Year 1968: A Reprise

December 1968 By EDWARD W. GUDE '59, INSTRUCTOR IN GOVERNMENT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

December 1968 By STANLEY H. SILVERMAN, EDWARD S. BROWN JR. -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

December 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1968 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

December 1968 By THOMAS J. SWARTZ JR., HERMAN E. MULLER JR.

Susan Liddicoat

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThird Panel Discussion

October 1951 By ALLAN NEVINS -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Better Understanding

Mar/Apr 2007 By ANDREA USEEM ’95 -

Feature

FeatureWHEN THE YOUNG TURKS CAME

December 1990 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureThe U.S.-Canadian Relationship

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29 -

Feature

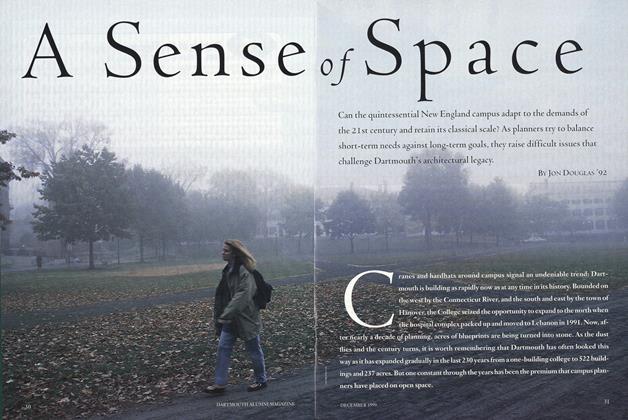

FeatureA Sense of Space

DECEMBER 1999 By Jon Douglas ’92 -

FEATURE

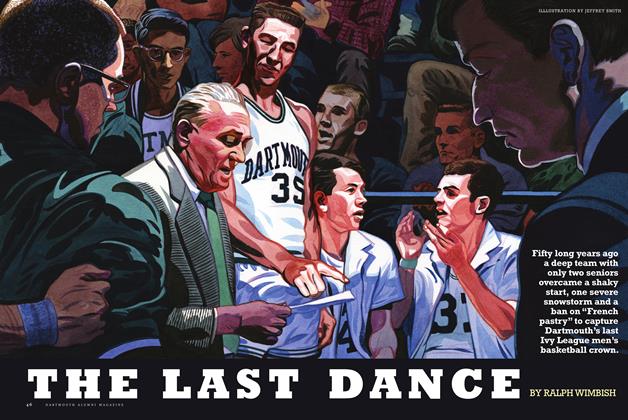

FEATUREThe Last Dance

Mar/Apr 2009 By RALPH WIMBISH