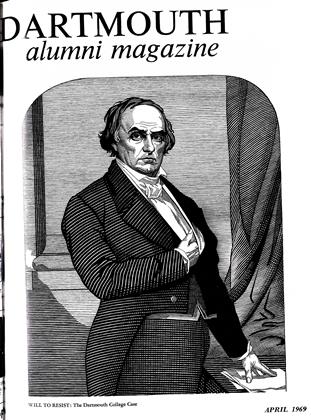

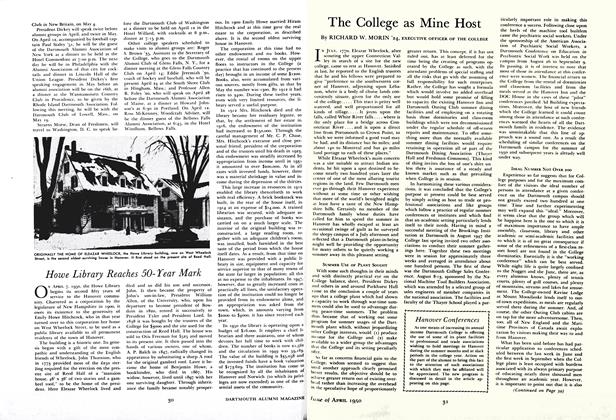

The Dartmouth College Case

Librarian of the College, Emeritus

150 years ago, in February 1819, the United States Supreme Court in the case of "Trustees of Dartmouth College vs. William H. Woodward rendered one of its landmark decisions. In a new account that concentrates on the College side of the case, Mr. Morin tells the full story of the controversy, from the first campus quarrel to the climax in Washington, where Daniel Webster successfully defended the independence of his alma mater.

THE Dartmouth College Case belongs to two societies. The first is the Dartmouth College family itself; the second is the larger community of legal A scholars and practitioners, and Constitutional historians. The College family tends to view with a mixture of pride and regret this required sharing. The second society - the professional one - regards the members of the first with a kind of amused tolerance. Unmoved by the dramatic rescue of a "small college," the professional society indulges the Dartmouth College family only so long as it does not insist on dealing in misty-eyed irrelevancies in its claim on the Case. It will not long be in doubt which of the two constituencies is the more favored in the following account.

Chartered in 1769 in the name of the British sovereign, George III, Dartmouth, the last of the Colonial colleges, was predesigned to test, fifty years later before the United States Supreme Court, the right of private education to survive. Behind the historic decision in Trustees of Dartmouth College v. William H. Woodward, known to lawyers and laymen alike as the Dartmouth College Case, lay years of upheaval and bitterness which cast into balance the very life of the institution. This festering torment, ended only by Chief Justice Marshall's opinion in 1819, took shape in the opening years of the nineteenth century. But it might be said to have had its earliest beginnings in a provision of the charter itself which authorized Eleazar Wheelock, founder and first President of the College, to name his own successor as President. At the time, in view of Eleazar Wheelock's single-handed elevation of the College from a dream to a reality, nothing could have seemed more natural than the granting to him of such a power. In fact, at the moment of the College's birth, and for long thereafter, it was impossible to distinguish between it and Wheelock, so completely did the former depend upon the energy, resourcefulness, and determination of the latter. Though the charter vested the supervision of the College in twelve Trustees of which Wheelock was but one, it was Wheelock who had in fact selected most of the Trustees appointed by the charter, and acquiesced in the remainder. Throughout Eleazar Wheelock's life those Trustees and their successors were content to leave to the founding father the entire control of the institution. His skillful guidance seemed to them evidence of the wisdom of such a course, and when Eleazar Wheelock by his will appointed his son John to succeed him it is probable that none among the Trustees conceived that a day could come when the Board would choose to exercise its charter power to remove John Wheelock from the presidency. On the contrary their dominant concern was to persuade John Wheelock to accept the office, in the face of his own reluctance to do so.

Putting aside his personal preferences, John Wheelock became the second President of Dartmouth College on October 19, 1779 at the age of 25. He was the second son of Eleazar, and actually had been his father's third choice to succeed him. His older brother, Ralph, who was his father's first choice as successor, had become incurably ill. The founder's second choice was his stepson, the Rev. John Maltby, whose death preceded Dr. Wheelock's. There appears to have been no consideration given to a selection outside the family. That a son should inherit the presidency followed naturally upon the founder's custom of looking upon the College as a private family preserve. After all, to whom did the College owe its existence? To George III in theory; to Colonial Governor John Wentworth as the instrument of the sovereign; but to Eleazar Wheelock in fact. On whom rested the authority not only for the day-to-day life of the College but for its fundamental direction and supervision? In theory on the Trustees perhaps; but in practice this responsibility was Eleazar's and his alone. Equally spontaneous was it for John Wheelock, once in office, to view himself as in every way his father's natural successor, in authority as well as title.

For the next 25 years John Wheelock reigned without challenge, dedicated and despotic. The early part of his rule was generally beneficial to the institution, despite his disposition to find too often an identity between his own interests and those of the College. This relatively smooth course might have continued indefinitely had no changes occurred in the makeup of the Board of Trustees. However, as Trustee replacements occurred in the early years of the nineteenth century, serene acceptance by the Board of all presidential acts began to fade, and in the face of opposition, John Wheelock exposed qualities of wilfulness which had not before come harmfully to the surface in his official conduct.

The instrument for polarizing Trustee opposition to John Wheelock was Nathaniel Niles. Elected to the Board as early as 1793, Niles was a Princeton graduate and resident of Fairlee, Vt. Qualified both as a lawyer and as a minister, he remained on the Board until 1820, a lone Republican* among Federalists. At first the Board's only independent voice, he was joined in 1801 by Thomas W. Thompson of Concord, N. H., a Harvard graduate, lawyer, Federalist Member of Congress, and later United States Senator. The next potential dissenter was Timothy Farrar, New Hampshire resident, graduate of Harvard, lawyer, and judge, who became a Trustee in 1804. Following him was Elijah Paine of Williamstown, Vt., elected to the Board in 1806. Like Farrar, Paine was a lawyer-judge; he was, moreover, a former United States Senator. Two

Trusters died between, the annual meetings of 1808 and 1809. one was old Professor John Smith, friend, admirer and subservient of both the Wheelocks, Dartmouth teacher since 1774 and Trustee since 1788, and a central factor in the hutch controversy later described. These two vacancies were filled at the August 1809 annual meeting by the elections of Charles Marsh of Woodstock, Vt., a Dartmouth graduate during John Wheelock's presidency and a lawyer by profession who had declined appointment to the Vermont Supreme Court; and Asa McFarland, also a Dartmouth graduate in the John Wheelock era, a former Dartmouth tutor, and at the time of his election the pastor of the First Congregational Church in Concord, N. H. Thus by 1809 there were already in office six of the eight Trustees later to make up the famous Octagon that stood in defiance of the powers of the State of New Hampshire to precipitate the Dartmouth College Case. Within the Board it was evident by that year that a serious conflict with President John Wheelock would be difficult to avoid.

THE collision between President and Board, though probably inevitable under the abrasive force of John Wheelock's imperious and demanding mien, arose directly out of the church controversy. This long, complex, and today almost incomprehensible struggle began in 1804 with the desire of a majority of the members of the local church to drop Professor Smith, who had long served as its pastor, in favor of the new Professor of Theology at the College, Roswell Shurtleff. President Wheelock was unwilling to see his personal control over the church thus weakened, a control made possible by the subservience of Professor Smith, its pastor. The disagreement heated into a quarrel which lasted for ten years during which John Wheelock called into play his extraordinary capacity for artfulness and dissimulation. His efforts to enlist the power of the Board on his side in the controversy partially succeeded in the early years when its majority was still supine. Wheelock's determination to rule or ruin (he was called Samson behind his back by foes and friends alike) split the church into two contesting fragments. As his hold over the whole weakened, he increased his efforts to enlist the official voice of the Trustees in support of his ends. Worried by the suspicion that they were being asked to act beyond their jurisdiction, the Trustees sought to be peacemakers. As is common to this role, they were reviled by both sides. The lack of success attending their halfhearted and informal endeavors increased their disposition to resist being drawn by the President into direct battle. When in 1811 Wheelock charged his Board with misappropriating the Phillips Fund (which supported the professorship of divinity) by permitting Professor Shurtleff to devote part of his time to preaching to that branch of the local church to which Wheelock was opposed, the Trustees by a vote of seven to three rejected the President's contention and for the first time took a formal stance in opposition to him. The same seven Trustees likewise noted that they had "long labored to restore the harmony which formerly prevailed in this Institution without success and it is with reluctance they express their apprehension that if the present state of things is suffered to remain any great length of time the College will be essentially injured."

At the same meeting the seven rebellious Trustees called into question the President's authority to determine by himself instances of delinquency among the students, and by the same split vote that authority was declared to rest not in the President alone but in a majority of the "Executive Officers of whom the President was only one, and the faculty the balance.

Other blows to the President occurred. In addition to the death of the pliable Professor Smith, he lost by the same cause a second supporter on the faculty. Their replacements, Professor Ebenezer Adams and Rev. Zephaniah Swift Moore, threatened his hegemony within the institution. Moore had been chosen by the Trustees contrary to Wheelock's express desire that the appointment be accorded to his sycophantic friend, the Rev. Elijah Parish. The wisdom of the Trustees was demonstrated when Parish later joined Wheelock in his anonymously printed attacks on the Board.

The Octagon was completed in 1813 when the Rev. Seth Payson of Rindge, N. H., was elected as Trustee to succeed the Rev. Dr. Burroughs, whose Trusteeship dated back to the days of Eleazar Wheelock's leadership. The President was left with but two supporters on the Board: former New Hampshire Governor John T. Gilman, Trustee since 1807, and Stephen Jacob, Windsor, Vt., lawyer, and Trustee since 1802. It could not then have come wholly as a surprise to John Wheelock when in November 1814 the Board voted that the President be "excused from hearing the recitations of the Senior Class. ..;" ostensibly to relieve him "from some portion of the burdens which unavoidably devolve on him." Simultaneously the Senior Class recitations were transferred to Professors Shurtleff, Adams, and Moore. (Up to this time, and until after the controversy was settled, the full teaching complement of the undergraduate college consisted of the President, three Professors, and two tutors. In addition two other Professors conducted the instruction at the recently established Dartmouth Medical School.)

A forcible curtailing of his teaching duties was an indignity which even a less volatile man than John Wheelock could not let pass. For him it was evidence that his situation had become desperate. Henceforth it was to be a battle without quarter. If he were to prevail he must enlist on his side the public and, if possible, the state legislature. To that end he offered to the College Trustees a resolution calling upon the legislature "to examine ... into the situation and circumstances of the College ... to enable them to rectify anything amiss " The Board voted down the resolution. Thus the base was cannily laid for an appeal to the legislature by Wheelock himself, in the role of a victim of a tyrannical Board unwilling to allow the State to examine it.

IT was the age of the printed tract, and John Wheelock chose that medium to arouse those who might support him against the Trustees. Consistent with his attachment to the devious, he elected to publish his diatribe anonymously, though so intelligent a man could hardly have expected that the identity of the author would long remain concealed.

Disingenuously entitling his pamphlet Sketches of the History of Dartmouth College and Moor's Charity School witha particular account of some late remarkable proceedingsfrom the year 1779 to the year 1815, Wheelock wrote it during the winter of 1814-15, with the help of his son-in-law, the Rev. William Allen, of Pittsfield, Mass., and Elijah Parish, the man whom Wheelock had been unable to persuade the Board to receive on the faculty. During the composition of the Sketches the President and Parish exchanged frequent letters The correspondence reveals a ludicrously conspiratorial design, and makes it clear that at least Parish derived the utmost titillation from the deviousness of its development. It was agreed that the latter should prepare, also anonymously, a Review of the Sketches for simultaneous publication. Of his Review Parish wrote Wheelock in March, "My object has been to keep my own temper and make everybody else angry . . . biting satire where the author . . . seems to say only what he is compelled to say, but yet like a soft secret gas it penetrates the very bones. . . . My object has been to make the reader respect the P____t, but despise the Pr_______f_s & hate the Tr_st__s." In truth this description could have been applied accurately to the Sketches themselves. The two pamphlets finally appeared in May 1815, and Wheelock and a few trusted friends immediately caused them to be widely distributed, not neglecting the members of the legislature due to convene in Concord the following month. In this he was aided by Isaac Hill, explosive editor of the New Hampshire Patriot and the most unrestrained voice in the State against the Federalist party. Hill saw an opportunity for the Republicans to make common cause with the beleaguered President against a Board of Trustees who, with the single exception of Niles, were Federalists, some possessing considerable influence in the councils of that party. Hill, and the others who took up the cry, found no difficulty in overlooking Wheelock's own record of Federalist sympathies.

THE period 1815-1820, during which the College controversy matured and was resolved, stands as a troubled one for the nation as a whole. The War of 1812 had just come to an end. Throughout the land the Federalist party was in bad repute largely because of an intemperate, single-minded, and some said seditious resistance to "Mr. Madison's war." In New Hampshire, Federalist attitudes had bred a deep distaste among the people, creating a fertile field to root a union of Republican antipathies and John Wheelock's grievances. The prospect of dealing a blow at Federalist pretensions was sufficient inducement to most New Hampshire Republicans to link themselves with the Wheelock cause.

The preparation of the Sketches seems not to have been anticipated by the Trustees, and thus the attack fell upon them without warning. In the course of 88 printed pages they found themselves charged, directly or by inference, with a bounteous list of sins: forcible change of "the first principles and design of the institution," misapplication and perversion of College funds, religious intolerance, arresting the College's progress and diminishing its financial resources, advancing the cause of a particular religious sect at the expense of others, neglecting the educational aims, secretly manipulating Board decisions, collusion in electing officers and Trustees against the President's wishes, packing the Board and College offices with supporters, depriving College officers of their religious rights and privileges, supporting a schism in the local church, violating the charter and remodelling the form of government it prescribed, destroying the constitutional rights of the President.

But most important to Wheelock's grand design was the claim that the Trustees held themselves "unamenable to a higher power," that is, to the state legislature. This was a theme that Parish elaborately embroidered in his Review, accusing the Trustees of making themselves an "independent government in an independent State," of constituting the Board an "organized aristocracy ... to manage the State," of possessing a will to "rule the State."

By plan the simultaneous appearance of the Sketches and the Review was quickly followed by a Memorial addressed by Wheelock to "The Honorable Senate and House of Repre sentatives, in General Court convened." In this he recalled "the patronage and munificence" which the State had ac corded the College, reminded the legislature of its uniqUe "power to correct or reform" abuses at the College, and cau' tioned that "those who hold in trust the concerns" of the College "have forsaken its original principles." Wheelock found reason to believe "that they [the Trustees] have applied property to purposes wholly alien from the intention of the donors," that they have "transformed the moral and religious order of the institution by depriving many of their innocent enjoyment of rights and privileges," that they have violated the charter by prostrating the rights with which it expressly invests the presidential office," and committed sundry additional offenses. A delayed fuse produced a final explosion. Said Wheelock, the Trustees were bent upon a "new system to strengthen the interests of party or sect which... will eventually effect the political independence of the people and move the springs of their government."

It was not Wheelock's invitation to the legislature to intervene that by itself so shook the Trustees. Exercises of the State's power in behalf of the College had been sought previously, and with some frequency, at the instigation of the Trustees themselves. But in this instance Wheelock's request for intercession was contrary to an express vote of the Trustees, and rested upon a monumental distortion of the truth. Outrageous as the charges must have appeared to anyone in possession of the facts, they were endowed by their manufacturer with a color of reasonableness calculated to arouse the sympathy of the uninformed. Most serious was the receptivity on the part of those legislators who were willing to regard the Board as a threat to the body politic, and indeed to the survival of democracy itself!

Before the Trustees had had time to develop a strategy for defense, a bill was introduced and passed by a large majority with eager Republican support in the June 1815 session of the legislature. It called for a committee "to investigate the concerns of Dartmouth College.... and the acts and proceedings of the Trustees ... and to report a statement of facts at the next Legislature." Wheelock wrote of his satisfaction to his brother-in-law, William Allen: "Our business is accomplished in the whole that I desired in my Memorial... the state are friendly to justice and the rights of humanity, and they begin to discover seriously the aristocratic spirit of the Junto." Thus the controversy between President and Trustees was almost overnight converted from a subject of loose gossip in limited circles into a major political issue with statewide implications.

The new phase was felt at once in the community of scholars on the Hanover plain. One student wrote to his father in July 1815: "This affair ... will ruin the College. If the President succeeds the Professors will leave.... This will be a death blow to the College, or at least its reputation will be destroyed for the present. But if the President should not succeed it is generally supposed ... he would establish another college at Concord which would soon rival this on account of the superior local advantages... . About 12 of my Class [1818] talk of leaving College to enter some others. ... Whether the President's charges are correct... I cannot say, but this I can say, I believe his conduct has not been altogether blameless."

The legislature's committee of enquiry elected to meet in Hanover in mid-August. Both the President and the Trustees were put on notice to be available for testimony. Wheelock on August 5 sent an urgent letter to Daniel Webster in Portsmouth requesting Webster to represent him at the committee hearing. But Webster was away and did not receive Wheelock's plea until too late. Even had he received it timely, Webster, as he later declared, would not have accepted the assignment. In contrast to present-day practice, he did not consider appearance before a legislative committee as a roper engagement of his professional services. He declared icily to a protagonist of Wheelock who upbraided him for letting the President down: "I regard that certainly as no professional call, and should consider myself as in some degree taking sides personally and individually for one of the parties by appearing as an advocate on such an occasion. This I should not choose to do until I know more of the merits of the case." Indeed Webster's sympathies already rested with the Trustees. His letter continued: "I certainly have felt, in common with everybody else as I supposed, a very strong desire that the Trustees, for many of whom I have the highest respect, should be able to refute in the fullest manner charges which if proved or admitted would be so disreputable to their characters." And Webster chided his correspondent gently about his readiness to believe ill of the Trustees: "I am not quite so fully convinced as you are that the President is altogether right and the Trustees altogether wrong. When I have your fulness of conviction perhaps I may have some part of your zeal."

As the committee hearing approached, Wheelock s anxieties increased and, having no word from Webster, he engaged Judge Hubbard of the Vermont Superior Court, a Windsor resident, to represent him. The committee met in Hanover at the President's house and at once concluded to "confine themselves to the consideration of the facts" relating "to such subjects as might be presented for this consideration by the President and by the Trustees." The President submitted to the hearing a written "specification of charges which did not extend beyond a single printed page when later published, as distinguished from the more than 80 pages that made up his undisciplined recital in the Sketches. It may be assumed that the constraints of a quasi-judicial hearing and the necessity for supporting his statement by "records, affidavits and other documents" mercifully squeezed out the surplusage.

The substance of the President's written charges was that the Trustees had improperly diverted College funds and had otherwise expended funds extravagantly, and had interfered with the proper functioning of the local church and with the charter powers of the President. The committee s report, not released until the following April, merely summarized the facts relating to the circumstances on which Wheelock relied to support his charges. It refrained from pronouncing judgment on the degree to which the facts sustained the accusations. But no reader could fail to be impressed by how feeble was the evidence, and it was not difficult to read between the neutral and unadorned lines a certain committee impatience with the man who had chosen to heat to the boiling point the internal affairs of the College. One wonders what damping effect the committee findings might have had on later unhappy developments in the legislature had the report received the wide readership attained by the sensational Sketches, instead of being obscured for eight months in the committee s files.

A few days after the legislative committee concluded its hearings the Trustees assembled in Hanover for their regular annual meeting, just preceding the Commencement ceremonies of August 1815. Present were the eleven men then making up the full Board of twelve Trustees, Governor Gilman holding office both as an elected and as an ex officio Trustee After the Board had proceeded routinely through two days of formalities, Charles Marsh introduced on the third day a resolution which took note of "two certain anonymous pamphlets" published since the last annual meeting, and proclaimed:

Whereas there is reason to believe that some member of this board or officer of the College is the author of or has had some agency in the publication of said pamphlets and whereas said pamphlets contain many charges defamatory to the board and individual members thereof and calculated to injure the reputahappy tion of this institution and impair the usefulness thereof, Resolved that a committee of three be appointed by ballot to enquire into the origin of the said pamphlets...

For the resolution were the eight votes of the Octagon and against it the votes of Governor Gilman and Mr. Jacob. Messrs. Thompson, Paine, and Payson were named to the committee. The Board adjourned to the following day when its committee reported that while "the nature of the case precludes the committee from obtaining positive evidence... evidence of a circumstantial kind has been obtained which leaves no room ... to doubt that President Wheelock was the principal if not the sole author of the pamphlet entitled Sketches of the History of Dartmouth College etc., and that through his means both the pamphlets mentioned were published and circulated." The report went on to list the evidence, including numerous public attributions of the Sketches to Wheelock "without any disavowal on his part" and "an anonymous letter in the handwriting of President Wheelock ... sent to Isaac Hill, Editor of the New Hampshire Patriot accompanied with a bundle of said pamphlets in which letter the said Hill was requested to distribute them among the members of the Legislature."

The President, who was not in attendance when the committee reported, was furnished a copy of the report and given an "opportunity to offer any explanation he sees fit to suggest" by ten o'clock the following morning. The President did not appear the next day, but filed with the Board a long letter entirely unresponsive to the issue of his role in the preparation and distribution of the Sketches. The President concluded by asserting that "considering the Honble Legislature of the State have, for the public good taken into their own hands to examine and regulate the concerns of the College ... it would be wholly improper and unbecoming me to submit to any trial on charges now exhibited before your body. ... I hereby protest against the proceedings ... and utterly deny your right of jurisdiction in the present case."

The Board thereupon by a vote of 10 to 0 affirmed its jurisdiction over the subject matter, and accepted the report by the earlier 8 to 2 vote. The Board then adopted by the same 8 to 2 vote a resolution removing Wheelock from the office of President of the College for which the following reasons were recited:

First He has had an agency in publishing & circulating a certain anonymous pamphlet entitled "Sketches of the History of Dartmouth College & Moors Charity School" & espoused the charges therein contained before the Committee of the Legislature. Whatever might be our views of the principles which had gained an ascendancy in the mind of President Wheelock we could not, without the most undeniable evidence have believed that he could have communicated sentiments so entirely repugnant to truth, or that any person who was not as destitute of discernment as of integrity would have charged on a public body as a crime those things which notoriously received his unqualified concurrence & some of which were done by his special recommendation - The Trustees consider the above mentioned public action as a gross and unprovoked libel on the Institution and the said Dr Wheelock neglects to take any measures to repair an injury which is directly aimed at its reputation & calculated to destroy its usefulness.

Secondly He has set up & insists on claims which the charter by no fair construction does allow - claims which in their operation would deprive the corporation of all its powers. He claims a right to exercise the whole executive authority of the College which the charter has expressly committed to "the Trustees with the President, Tutors & Professors by them appointed" — He also seems to claim a right to control the corporation in the appointment of executive officers, inasmuch as he has reproached them with great severity for chusing men who do not in all respects meet his wishes & thereby embarrasses the proceedings of the board.

Thirdly From a variety of circumstances the Trustees have had reason to conclude, that he has embarrassed the proceedings of the executive officers by causing an impression to be made on the minds of such students as have fallen under censure for transgressions of the laws of the institution, that if he could have had his will they would not have suffered disgrace or punishment.

Fourthly The Trustees have obtained satisfactory evidence that Dr Wheelock has been guilty of manifest fraud in the application of the funds of Moors School by taking a youth who was not an indian, but adopted by an Indian tribe under an indian name, and supporting him on the Scotch fund, which was granted for the sole purpose of instructing & civilizing Indians. -

Fifthly It is manifest to the Trustees, that Dr. Wheelock has in various ways given rise and circulation to a report that the real cause of the dissatisfaction of the Trustees with him was diversity of religious opinions between him and them when in truth and in fact no such diversity was known or is now known to exist as he has publickly acknowledged before the committee of the Legislature appointed to investigate the affairs of the College.

The Trustees went on to say that they had acted "from a deep conviction that the College can no longer prosper under his presidency."

Governor Gilman and Mr. Jacob, the two dissenters, denied the Board's authority to remove the President, and the charge of fraud against Wheelock in the application of the funds of Moors School as unsupported by the evidence.

The Board then proceeded to elect the Rev. Francis Brown of North Yarmouth, Maine, as President of Dartmouth College, having had indications from one of the Trustees that Brown would not refuse. A committee was appointed to inform Brown and request his acceptance. After adopting a "statement of facts" summarizing what had taken place at this momentous board meeting, the Trustees adjourned, naming a September date one month hence to reassemble.

During the interval there occurred the publication of the Trustees' answer to the Sketches which they tided A Vindication of the Official Conduct of the Trustees of DartmouthCollege. They elected to offer it for purchase only, at fifty cents, though the Sketches had been available for the asking and had indeed been thrust upon all willing readers. Those persons who made the effort to secure and read the Vindication must have found in it telling answers to accusations made by the Sketches. Meticulously drafted (after all it was the joint work of two of the lawyers on the Board) it contrasted sharply with the Sketches, both as to claims and style. The tool was the scalpel rather than Wheelock's broad axe, but each was equally dipped in venom.

ON September 26 the Board reassembled to welcome Francis Brown to the presidency. Only the Octagon were present for the occasion and for the simple inauguration ceremonies which followed. It was to be the last meeting of the Trustees before the legislature brought down the walls upon them.

From the moment the legislature had appointed its factfinding committee in the preceding spring there had hung over the Trustees a pervasive worry as to what steps might ultimately be taken. They were mindful that Wheelock's maneuvering had enlisted some highly influential, if shrill, voices among the Republicans at a time when there was reason to expect the Republicans might upset the Federalists in the state elections scheduled for March 1816. Moreover, the probable Republican candidate for Governor, William Plumer, was known to be highly impatient with the controversy that had disrupted the College. The Trustees were likewise mindful that the Wheelock attributions to them of an uncompromising religious orthodoxy would arouse the religious liberals in the State, regardless of their party affiliations.

Many friends of the College shared the Trustees' apprehension. Jeremiah Mason, then a United States Senator, leading Federalist and later one of the College's counsel, had written to his cousin, Trustee Charles Marsh, in mid-August indicating he had heard rumors of the Board's intention to remove the President. "I greatly fear," said Mason, "such a measure adopted under present circumstances ... would have a very unhappy effect on the public mind." Mason noted that a legislative enquiry was pending and declared that "the Legislature ... for certain purposes have a right to enquire into alleged mismanagement of such an institution. ... Should the Trustees during the pendency of the enquiry ... take the judgment into their own hands by destroying the other party, they will offend and irritate at least all those who were in favor of making the enquiry. ... If the statements of the President are as incorrect as I have heard it confidently asserted an exposure of that incorrectness will put the public opinion right. It may require time but the results must be certain. ... A very decisive course against the president by the Trustees at the present time would create an pleasant sensation in the public mind, and would I fear be attended with unpleasant circumstances." Mason excused himself for expressing so strong an opinion on a subject "in which I have only a common interest." He confessed, he said to being "somewhat influenced by fears that some of the Trustees will find it difficult to free themselves entirely from the effects of the severe irritation they must have lately experienced."

Mason's warning was before the Board at the time the dismissal of the President occurred, and they endeavored to counteract the effects which Mason anticipated by associating with the resolution of dismissal a declaration that "the measure cannot be construed into any disrespect to the Legislature of New Hampshire whose sole object in the appointment of a committee to investigate the affairs of the College must have been to ascertain if the Trustees had not forfeited their charter and not whether they had exercised their charter powers discreetly or indiscreetly - not whether they had treated either of the executive officers of the College with propriety or impropriety." The weakness of the Trustees' disclaimer was that, though it enunciated a good legal principle, the distinction which it drew was too esoteric to make a public impression. Another astute observer correctly predicted a public revulsion at the Wheelock removal which "will probably bring in Plumer [expected Republican candidate for Governor]", and produce a "revolution in the Politicks of the State" to continue until it has "destroyed one of the fairest Literary Institutions of the Country." Such a forecast came perilously close to realization.

The Trustees clung to the hope that their dismissal of the President would in fact quiet down the furor, as was indicated in Marsh's reply to Mason, written after the dismissal had occurred. Likewise clear from Marsh's letter was the conviction that they had no real alternative to the dismissal. "I only regret" wrote Marsh to Mason, "that you, Mr. Webster and some few others could not have been with us [at the Trustees meeting at which Wheelock was removed] and have taken a view of the whole ground." If the President had been left in office, asserted Marsh, he would have retained powers of resistance "which he cannot now call into action. ... The decisive measure being taken, we think that Federalists who under other circumstances might be otherwise inclined will abandon the concerns of the College to the care of the Trustees and still rally around the standard of political party.

Events moved swiftly in the ensuing months. John Wheelock had warned Francis Brown before the latter s inauguration that he, Wheelock, would continue to consider himself "the rightful President of Dartmouth College" and that he felt confirmed in this view "by the tenor and spirit of the charter and by high authorities in Law." Wheelock conducted himself accordingly and forbade tenants of the institution to pay rent to any but himself. He received communications of support from sundry sources, including one from Elisha Ticknor, successful Boston merchant and father of George Ticknor. Reports from elsewhere in Massachusetts and from Portsmouth indicated widespread sympathy with him. The New Hampshire press, virulent whenever it spoke, was divided in its support, with the balance probably in favor of Wheelock.

William H. Woodward, Secretary and Treasurer of the Board and nephew of the deposed President, had forsaken the Trustees to stand by his uncle; and Mills Olcott, lawyer and long-time Hanover resident, had been appointed to fill the Woodward offices. Thus locally the affairs of the Trustees rested in the hands of President Brown and Olcott. Brown sought to establish his authority in the eyes of tenants of College properties. But the latter refused to pay the rents so long as Doctor Wheelock claims them likewise." This was a blow to the College as it was desperately in need of funds.

Among the Hanover citizenry the majority seemed to favor the Trustees but there were some conspicuous exceptions including, embarrassingly, Dr. Cyrus Perkins, principal figure at the Dartmouth Medical School. For the rest the faculty were in full support of the Trustees. Apprehension among the students is illustrated by a letter which Rufus Choate, then in his first year at Dartmouth, wrote in early March 1816. "Respecting the affairs of this College," said Choate, "everything is at present in dread uncertainty. A storm seems to be gathering ... and may burst on the present government of the College.... If the State be Democratic a revolution will take place, probably President Brown may be dismissed. In that case the College will fall."

As the March 1816 New Hampshire elections approached Trustee Thompson, then attending as a Senator the session of Congress in Washington, wrote his brother-in-law, Mills Olcott, in Hanover: "I do hope & pray that our friends throughout the State will duly appreciate the necessity of making an extraordinary exertion for the preservation of the College. ..." Thompson, who shared rooms in Washington with Daniel Webster, observed that "we talk up the affairs of learning and politics at a great rate." Trustee Charles Marsh was likewise serving in Washington as a member of Congress from Vermont, and shared lodgings there with his cousin Jeremiah Mason. There were thus unhappily removed from the New Hampshire scene four of its most influential Federalists who might have helped guide opinion in the State away from the Republican view. However, they made the most of their association in Washington, with Marsh filling the role of principal correspondent with President Brown and the other Trustees.

The Federalists had nominated James Sheafe for Governor, while the Republicans selected as their candidate William Plumer, a former United States Senator from New Hampshire, and one who had not been reticent in expressing his displeasure at the state of affairs at Dartmouth College. After his nomination Plumer wrote to Col. Ames Brewster, a Wheelock supporter in Hanover:

From the information I have received from various parts of the State there is a high probability that in every branch of the government this year there will be a Republican majority, and I think a cordial disposition to do justice to the injured Wheelock. If I should have any part to act in the government I will make at least an effort to reduce the wrong he has suffered and repair the injuries that have been arbitrarily inflicted on the literary institution which he has nurtured and over which he has so long and ably presided. Will it not be requisite that his friends in your vicinity should before June [when the new Legislature was to convene] devise a system not only to restore him to his rights but to prevent the College being again exposed to similar evils?

Plumer's election was overwhelming and, contrary to the Trustees' hopes and indeed expectations, it came about not only through Republican support but also the support of many Federalist friends of John Wheelock. That public opinion — or at least opinion in influential circles - was now running against the Trustees became all too clear. In early April President Brown wrote to a clerical colleague who had some acquaintance with the new Governor and with Samuel Bell, Dartmouth 1793, another towering Republican figure whom the new Governor was about to appoint to the New Hampshire Superior Court. Brown spoke of the Trustees' and his own desire to "disseminate correct information among men of influence," deplored "the accidental circumstance that some leading Federalists in the State belong to the Board of Trustees has been seized by Dr. W. as furnishing him with the means of enlisting on his side the political feelings of the opposition party," denied "that political considerations were among the inducements of the Dr's removal," and declared wistfully that "those who have not been brought to act with Dr. Wheelock know very little of the man. And those who have long acted with him are frequently surprised by some new exhibition of his character." Brown covered dispassionately and in some detail the facts of the controversy from the Trustees' viewpoint, and then concluded with the following appeal:

I have thought that at this time of excitement and general anxiety respecting the College this communication might not be unacceptable to you nor without its use to us. In the company of your friends I wish you to make that use of its contents which you judge to be prudent and proper. I mention particularly the Hon. Sam1 Bell with whom I have not had the pleasure of an acquaintance, but who has been a Trustee of the College and who I think, might employ an influence for our benefit. With the Hon. Mr. Plumer's feeling in relation to the College I have not been made acquainted. I have no doubt however that measures have been taken before this time by Dr. W. to induce him to insert a paragraph into his speech or message at the opening of the Legislature bearing on the Trustees. I hope he will think proper to omit the College dispute altogether or if he should speak of it to avoid anything more than to announce the general subject.

Meanwhile Congressman Marsh in Washington, through letters to President Brown in Hanover and to the other Trustees, endeavored to develop a strategy to forestall action by the legislature adverse to the Trustees. But only Senator Thompson among the principal Washington strategists could be in Concord for the opening of the legislature in June There he was joined by his fellow Trustees, Asa McFarland and Elijah Paine, as representatives of the Board, and President Brown was likewise on hand to observe the events at. fecting the College.

When Governor Plumer addressed the legislature on June 6 he noted that the College's charter had "emanated from royalty" and "contained ... principles congenial to monarchy," including the provision for a self-perpetuating Board of Trustees. This provision he called "hostile to the spirit and genius of a free government." Plumer claimed a right for the State "to amend and improve acts of incorporation of this nature." The Governor's message and the belated report of the fact-finding committee which had met in Hanover the preceding August were referred to a special committee of legislators. Without waiting for the report of the Hanover hearing to be printed the special committee brought in a bill entitled "An act to amend, enlarge and improve the Corporation of Dartmouth College." Despite formal remonstrance by the representatives of the Trustees and an offer by them, fortunately rejected, to compromise by accepting a Board of Overseers drawn from State officers with a veto over the Trustees, an act was passed by both houses voting along party lines.

To concede by hindsight that Jeremiah Mason was right and the Trustees wrong in their evaluation of the consequences of their dismissal of John Wheelock by no means leads to a conclusion that the dismissal should not have been made when it was. With comfortable Republican majorities in both houses of the legislature supporting a Republican Governor, it is probable that forbearance on the part of the Trustees would not have forestalled the fateful June 1816 legislation. On the other hand, if they had continued to be saddled with an antagonistic President and had lacked the extraordinary leadership of the new President Francis Brown, their capacity to resist the consequences of the legislature's determined attack would have been immeasurably reduced.

The legislation altered the name of the institution from the "Trustees of Dartmouth College" to the "Trustees of Dartmouth University."* It increased the number of Trustees from 12 to 21, "the majority of whom shall form a quorum for the transaction of business" ( a petard which later hoisted the University Trustees in a most embarrassing way). The new Board was given "all the powers, authorities, rights, property, liberties, privileges and immunities which have hitherto been possessed ... by the Trustees of Dartmouth College." Another provision created "a Board of

Overseers, who shall have perpetual succession and whose number shall be twenty-five," with power to "confirm, or disapprove ... votes and proceedings of the Board of Trustees." From New Hampshire the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House, and from Vermont the Governor and Lieutenant Governor, were made ex officio Overseers. The New Hampshire Governor and Council were given autthority to "fill all the vacancies on the Board of Overseers and "complete the present Board of Trustees to the number of twenty-one ... and ... to fill all vacancies that may occur previous to, or during the first meeting of the said Board of Trustees" Finally the Governor was authorized "to summon the first meeting of ... Trustees and Overseers to be held at Hanover on the 26th day of August next."

The effect of the enactment upon the Trustees was stunning nor was it the more acceptable for being inevitable. "I cannot endure the pain," wrote Senator Thompson who had witnessed the legislature's headstrong attack, "to recollect the proceedings ... much less can I bring myself to write the disgusting details Our friends belonging to the Legislature 3and every other one whom I have met advise us to refuse to accept the new act or to accede in any shape to the new Legislature's modifications." A few days later Charles Marsh in response to an enquiry from President Brown gave his view that "the act is altogether unconstitutional and must be so decided could the question come before a competent and dispassionate court." Marsh, too, urged resisting the act rather than yielding. Thompson on a visit to Portsmouth where he found much pro-College sentiment, conferred with his fellow Trustee, Timothy Farrar, and with Daniel Webster and Jeremiah Mason. He reported their common view to be that the Trustees should maintain the original corporate rights and try the issue.' Farrar urged an immediate approach to Jeremiah Smith, as well as to Mason and Webster, to obtain their guidance as to what specific measures should be pursued.

Thompson recommended that President Brown call a meeting of the Trustees for late August to decide upon a course of action. The meeting should be, said Marsh, in precisely `the same style as though the Legislature [had] not attempted to interfere." He stressed the importance of the Trustees avoiding "every act which can be construed into a recognition of the authority of the Legislature to encroach on our powers and rights in the manner they have attempted to dO. ... Our adversaries must be aware that ... we shall at some time or other be able to ... unravel all their proceedings. This consideration will probably check them more than any other.... The measure of resistance ... is the only one which ... affords any share of hope.... [We must] go as far as we can ... to execute the powers vested in us by the Charter, and when we have gone this far to adopt the Quaker system of withholding our active cooperation in anything done by others - we must continue to keep this corporation alive."

These brave words, at a dismally low point in the College's fortunes, were a clear call to civil disobedience. But Marsh also had an eye for the practical difficulties, of which one was the College's extreme shortage of funds. Particularly was he solicitous about the precarious financial situation of President Brown. "I feel this subject much at heart" he wrote the President, "and especially when I reflect how much trouble and anxiety you ... have experienced." Characteristically, Brown seemed to worry far less about his plight than did his associates.

Meanwhile, in late July the Governor and Council, exercising their new authority, appointed nine new "Trustees of Dartmouth University," which with the twelve old Trustees would complete the complement of twenty-one prescribed by the legislature. At the same time, the twenty-one members of the new Board of Overseers were named. That advance consent to serve had not been obtained in all cases is evident from the refusal of membership by Justice Joseph Story of the United States Supreme Court whom Plumer had listed among his appointments.

The legislature had carefully prescribed August 26 as the date of the first meeting of the new Board, and Hanover as the location. When the Governor sent notices of the meeting to the old Trustees the responses were in most instances discreet and noncommittal. The replies of Trustees Farrar and Payson were perhaps a bit more expansive than the circumstances required, but this merely illustrated that while these two men were actively aligned with the Octagon, they were by age and preoccupation a bit more removed from the center of strategy planning than were, for example, Marsh, Thompson, McFarland and, of course, Brown.

PRESIDENT BROWN issued his call for a Hanover meeting of the College Trustees for the same date that the statute had fixed for the University Board meeting. When the appointed time arrived - Monday, August 26, 1816 — there ensued a ludicrous two-day minuet between Governor Plumer, as temporary chairman of the University Board, and President Brown, each declining to recognize the existence of the other's Board. Plumer and his followers met in the office of the disaffected College Treasurer, William. H. Woodward, while the College Trustees met in the study of President Brown. At the Plumer meeting but nine persons were in attendance out of the full complement of twenty-one. Among these was Stephen Jacob, the only Trustee present from the old Board. Others formerly identified with the College were William H. Woodward and Cyrus Perkins. Also in attendance was Levi Woodbury, Dartmouth 1809, later appointed by Governor Plumer as judge of the New Hampshire Superior Court.

Present at the meeting of the College Board, in addition to President Brown, were Thompson, Farrar, Paine, Marsh, McFarland, Smith, and Payson. Of the Octagon only Niles was missing. By that time all had formally declined to attend the Governor's meeting. The old Board's first act of business was to adopt a defiant resolution of resistance. "We the Trustees of Dartmouth College do not accept the provisions of an act of the Legislature of New Hampshire approved June 27 ... but do hereby expressly refuse to act under the same."

President Brown immediately transmitted the resolution to the University Board. The point of no return had in effect been reached.

At least the five lawyers among the Octagon could have been under no illusions about the seriousness of the step they had chosen to take. Yet the solemnity of the situation had it moments of comic relief. The old Trustees saw their strategy succeed when the unhappy Governor Plumer, after fruitless summons to President Brown and associates to attend the University Board meeting, was unable to obtain a quorum. In consequence the Governor was forced to declare his meeting adjourned, without his Board having been able even to organize, to say nothing of taking substantive action.

It was not an outcome designed to endear the old Trustees to the Governor. Nor was his discomfiture relieved when he learned that so tightly had the legislature seen fit to prescribe the time and place for the first Board meeting, and his powers with respect thereto, that a miscarriage having occurred, he was without authority, until corrective legislation could be obtained, to call another meeting.

This contretemps left Francis Brown, his Board, and his loyal faculty unexpectedly in undisputed charge of the institution. The 1816 Commencement exercises followed immediately upon the Trustees' decision to resist. It was to be the last such ceremony without threat of University interference until 1819. The occasion produced an unexpected and munificent gift to the College from John B. Wheeler, an Orford N. H., merchant. His donation of $1000 was intended to enable the Trustees, in his words, "to test their rights by a suit at law." The amount was the equivalent of two-thirds of a whole year's endowment income. While the full measure of the Trustees' gratitude was not registered until nearly ninety years later when a new dormitory was named Wheeler Hall, the gift produced immediate and enormous benefits, both real and psychological.* Over the College community hung the full weight of ultimate uncertainties. "It is to be feared that the best days of this institution are over," wrote one student to a friend. "Should the game be pursued the sons of Dartmouth may prepare to see their alma mater thrown into convulsive agitation from which she cannot recover ... we may expect an overturn here. In that case I shall go to some other college."

The College Trustees again gathered in Hanover for a Board meeting of their own on September 29, 1816. Their first act then was to issue a call to William H. Woodward, still officially holding the office of Secretary of the Board, to attend and deliver "the records and seal appertaining to the office of Secretary." Not unexpectedly Woodward refused either to attend or to deliver the items demanded, whereupon the old Trustees removed him from office and appointed Mills Olcott in his stead.

The reopening of College in October produced about the same number of students as in the preceding academic year, reported Professor Adams. The Professors found, too, that in Hanover "current opinion has been setting more and more favorably for the old Trustees ever since Commencement." A quiet but determined contest prevailed between the officers of the two institutions to collect rents on College properties; but the tenants, understandably, continued to refuse risking wrong payment.

In November the Governor requested enabling legislation to permit calling the University Board together. The legislature readily responded in December by amending the quorum requirements and resolving ambiguities as to the Governor's authority to assemble the new Board. Student Rufus Choate on December 16 in a letter to his brother described the new legislation as "authorizing nine of the new Trustees only to do business, a number which it is supposed can very easily at any time be assembled. That the body will convene immediately perhaps before the end of the term and remove the whole of the present government of the College

and supply their places with men of their own party is whar the best informed among us confidently expect."

As the year 1816, so full of portent, drew to a close, President Brown polled his Trustees on a proposal to attempt through the courts to obtain a recognition of their charter rights and a rejection of the legislature's effort to alter them Brown noted that Mills Olcott was securing an informal opinion from Jeremiah Mason on what action to take. Before replies could be received from the Trustees the legislature took a further step, seeming to justify Marsh's earlier judgment expressed to Brown that "no one can tell ... what in the wantonness of power they may have the madness to attempt." On December 26, 1816 there was passed a statute which came to be known as "the penal act." It provided that anyone who purported to exercise authority on behalf of the institution, except pursuant to the legislation which had established the University, would be subject to a forfeiture of $500, "to be recovered by any person who shall sue therefor, one half thereof to the use of the prosecutor and the other half to the use of said University." This oppressive hunting license contained the possibility of breaking the old Trustees" as well as the faculty associated with them in operating the College. The $500 penalty was not limited to but one application; it extended to each forbidden act by each individual. Thus, in the course of a single meeting of the old Board each Trustee could conceivably be exposed to a dozen forfeitures each of $500, depending on how many pieces of business were handled at the meeting. The conducting of every class of instruction subjected each loyal faculty member to a similar forfeiture.

JANUARY 1817 was an anguished month for the College Trustees. The "penal act" put their strength of purpose to a severe test. Particularly worried was Senator Thompson whose family obligations and financial resources seemed precariously balanced. Marsh, too, suffered moments of indecision. On the other hand, Judge Farrar ("the sooner the question is decided the better it will be for the College") and Judge Paine ("the only way is to persevere fully in the old order. ... We ought not to look back") urged a prompt contesting of the legislation. Perhaps bravest among the Trustees, because he trusted most, was the Reverend Asa McFarland, Concord clergyman and youngest member of the Board. Unlearned in the law himself, he supported solely on faith a prompt initiating of legal action. The disquietude of Thompson and Marsh subsided, and by the latter part of January they were in full, and indeed enthusiastic, support of a course of resistance to the end.

It is impossible to weigh fully the influence of an occurrence of the first importance at this moment. Hamilton College, having just lost its president by death, offered the succession to Francis Brown, at double his Dartmouth salary, and of course with assurance that his compensation, whatever it was, would in fact be paid. Hamilton was already a well-established, highly respected, and relatively prosperous college with an unclouded future. That Brown, despite this temptation and under the most trying conditions, elected to remain as the head of an institution with so dubious a future is telling evidence of the character of this extraordinary man. It is hardly an exaggeration to say, as surely his Trustees themselves felt, that Dartmouth College would have suffered a staggering blow in Brown's departure. There was literally no one else to carry on his kind of inspired leadership, without out which the whole cause of the College might well have foundered. Brown's decision put new strength and determination into the Trustees.

Next to be faced was a troublesome, if secondary problem Throughout much of the nineteenth century, American courts and lawyers were severely trammeled by a complex of intricate formalities and procedural requirements for commencing litigation. Inherited from English common law, the rites whatever may have been their justification in earlier centuries, had become by this time obsolete accretions serving only to trip up litigants and their lawyers and to harass courts with a proliferation of hearings on basically irrelevant issues. The launching of a suit by the Trustees was, in common with others at this period, beset by the peril of selecting the wrong procedural approach and in consequence encountering an adverse decision on what today would be regarded as an unconscionable technicality. Diverse views among the lawyer Trustees on precisely what form of action to elect were at last resolved, with the aid of counsel, by fixing upon an action in trover against William Woodward in the name of the Trustees of Dartmouth College for the recovery of the minutes of Trustees meetings, the original charter, the seal, and sundry account books, all of which Woodward had retained in his possession on his defection to the new Board.

On February 8, 1817 suit was initiated in the Court of Common Pleas for Grafton County and immediately transferred to the Superior Court of the State of New Hampshire. This was then the State's highest court and ordinarily an appeal court, but the lower Court of Common Pleas was bypassed because the defendant, William Woodward, was himself a judge of that court. Thus the Dartmouth College Case began.

While the strategy of the College had been taking shape, the cause of the University had been suffering. Not until February 4, 1817 did the University Trustees come together in Concord for their first regular meeting. Even then it took two days before a quorum could be obtained, so unwieldy was the size of the Board and so devoid of deep commitment were most of its members. Meanwhile, the two principal University adherents in Hanover had become seriously incapacitated by ill health. Woodward himself, on whom much depended, was so plagued by illness that he briefly contemplated not attending the Concord meeting. But, more seriously, John Wheelock's health had so declined that it was clear his affliction was terminal. The University Trustees were thus denied on-the-scene agents comparable in interest, if not in ability, to Francis Brown and Mills Olcott for the College, a deficiency which was not overcome by the recruiting of William Allen and Dr. Cyrus Perkins in corresponding positions for the University.

The University Board proceeded at the Concord meeting to "discharge and remove" from office President Brown, the resisting Trustees, and the two non-cooperating faculty members, Professors Roswell Shurtleff and Ebenezer Adams, all of whom until then nominally held University positions on the theory that the University was successor to the College. Fully recognizing that the state of Wheelock's health precluded his serving as president of the University the new Trustees nonetheless elected him to that office, providing at the same time that the duties of the presidency should be discharged by Wheelock's son-in-law, William Allen. The latter was likewise appointed Phillips Professor of Theology to succeed the deposed Shurtleff. Allen, then 33 years old (he and Francis Brown were only nine days apart in age), was a graduate of Harvard. Son and grandson of clergymen, he had studied theology in Brookline, Mass., and in 1810 took over his father's First Congregational Church in Pittsfield, Mass., where he remained until coming to Hanover in 1817. In 1813 he had married Maria Malleville Wheelock, John Wheelock's only child. Allen has been variously described by contemporaries as "inflexible," "stately," "stiff,' "unyielding." His manner was said to provoke opposition both from students and associates.

The University Trustees appointed three of their Hanover adherents, Dr. Cyrus Perkins, Amos Brewster, and James Poole, as "superintendants of the College buildings" and directed them "to take possession of the College [as Dartmouth Hall was then known], Chapel and Commons Hall and cause them to be well provided with suitable fastnesses ... and prevent intrusion by any." This triumvirate made demand on President Brown for the key to the Chapel and on Professor Shurtleff for the key to the library. Both declined to accede, whereupon the "superintendants" without further formalities occupied Dartmouth Hall ("the College"), which housed the library, and the adjoining chapel building. This confrontation was brief and, unlike a later one, nonviolent. In early March Rufus Choate reported the affair from the student viewpoint in a letter to his brother:

The partisans of Plumer ... took possession of the College buildings and Library and opened the campaign ... by uniting in prayer literally with but a single student in the Chapel! President Brown and friends immediately engaged a large and convenient hall as a chapel and entered it that same morning with every scholar in town but the one above-mentioned. The students [have] now nearly all [returned for the opening of a new term] and the following is the number on the side of the university; freshmen none, Sophomores 2, juniors 1, seniors 4; total 7. Possibly 2 or 3 more may join them....

Another student, a junior in the College, wrote to his brother:

The College students have equally as good instruction as they have had for years past, and their advantages are the same except that we have not access to the College Library. However there are such a variety of books in the Society Libraries it is not considered much of a loss. ... It appears to be the determination of the old officers not to be frightened from their ranks until it be legally decided, and if it be determined against them, and there is no appeal, undoubtedly a large number of the students will leave. They will not join the University. We wait with anxiety to know the results.

Dr. Nathan Smith, iconoclast, founder and professor of the Dartmouth Medical School, wrote to Mills Olcott from New Haven: "If there should be a prospect of a pitched battle between the College and the University I hope it will take place before my arrival, as I have not forgotten the sage advice of Falstaff that it is best to come in at the beginning of a feast, and the latter end of a fray."

Though Choate scornfully dismissed the few students who supported the University authorities, the students on the side of the College did not possess all the commitment. A member of the Class of 1817 wrote in early April:

When I reached Hanover I found division among the students. ... I did not hesitate to enlist under our ancient President [Wheelock] though his followers were but few, only fourteen and they are but fifteen now. ... I did not wish to join to assist men whom I considered to be engaged in a bad cause. ... Dr. Brown, Adams, Shurtleff have left the university and are reduced to the miserable necessity of making a hall a sanctuary for their divinities and to occupy kitchens for recitation rooms. They have no library ... and teach as private instructors, each class pay their own masters. ... The situation of the old Board is, as all parties ought to be who resist the laws, distressing.

Almost the last rational acts of John Wheelock were three for the benefit of the University. The first was a conveyance to the University of extensive lands to support a president, contingent upon the validity of the legislation creating the University, and to revert to Wheelock's heirs if the legislation failed. Second was a release to the University of a debt of $6000 said to be owing to him for back salary. Third was the execution of his will granting further lands to the University to establish professorships in Mathematics and Greek, again with the proviso that if the legislation on which the University rested should fail the lands should go elsewhere, this time not to his heirs but to the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church for the use of the Theological Seminary at Princeton University. The unevenness of his signatures on these documents evidenced the critical state of his health.

The following month John Wheelock died, mercifully spared knowledge of the outcome of his elaborate scheme to put down his enemies. William Allen was elected to succeed him as President of Dartmouth University. One is impelled to reflect on what would have been the result for Dartmouth, and for other private educational institutions, had the Trustees not so constricted Wheelock that he felt driven to break openly with them scarcely a year and a half before his death. With a few more months of Trustee forbearance the chain of events that radically altered the history of private education in America might not have been set in motion.

IN almost fortuitous union of forces brought about the successful weathering of the College's ordeal. Evidence of two of these has already been seen: the profound personal involvement of several key Trustees, and the steadfast leadership of President Brown. Now to unfold was a third: the preeminence of the College's legal counsel. It is doubtful that the final triumph could have come about had any one of these three elements been lacking.

Beyond all challenge the two senior leaders of the New Hampshire bar at this time were Jeremiah Smith and Jeremiah Mason. Smith, a native New Hampshireman and in his 59th year when the case opened, had been in practice or on the bench for nearly thirty years. During that period he had also served New Hampshire in the United States Congress, fulfilled one term as Governor of the State, and ten years as its Chief Justice. With the defeat of the Federalists in 1816 he had returned to private practice in Exeter. A strong Federalist and hostile to Jeffersonian doctrines, Judge Smith had a reputation for caustic wit which he visited freely, in and out of court, upon friend and foe alike.

Mason, nine years younger than Smith, was born in Connecticut. After graduation from Yale he came to New Hampshire, later taking up residence in Portsmouth, then the largest town in the State. For many years he held undisputed supremacy among Portsmouth lawyers, challenged only by Daniel Webster during the latter's brief practice in that place. During his long residence in New Hampshire Mason served as Attorney General of the State and as a Federalist member of the United States Senate. In 1816 he declined to accept appointment as Chief Justice of the New Hampshire Superior Court. When the Dartmouth College Case came on for trial before that court Mason was considered to be among the greatest lawyers of his time. Standing six feet and six inches, he was an imposing courtroom figure.

The third and junior counsel was Daniel Webster, then 35 years old. As the only Dartmouth alumnus among the three, his relation with the College had been more intimate than the others, though Smith as Governor of the State had served briefly as an ex officio Trustee. In 1816 Webster moved from Portsmouth to Boston. When the case opened he was still much occupied in getting established in his new location, and perhaps in consequence of that his role in the litigation while it was before the New Hampshire court was minor, compared with the participation of Smith and Mason.

It is not clear why Mills Olcott, acting as the Trustees' agent, delayed so long after filing suit before formally retaining counsel. Two months earlier he had consulted Jeremiah Smith on procedural technicalities, and in Washington, Marsh and Thompson had maintained a dialogue on the issues with Jeremiah Mason, fellow member of the national legislature. By letter Thompson too had laid a few of the questions before Webster for his informal views. But as late as mid-April 1817, and only a month before the first hearing of the case was due to occur, there was still some ambiguity about who was representing whom. A friend of the College wrote from Portsmouth to Francis Brown on April 11 that Mason had just turned aside an approach by the University to represent its side, at the same time asserting that "he has not been at all consulted [by the College] in the commencing or conducting of a suit." Thompson wrote to Olcott as late as April 25 saying "Judge Smith talks as if he were not under obligation to prepare himself to argue our College cause next month. I do not know what this means. ... If any further application is necessary or any fee pray take the necessary steps."

The "necessary steps" were in fact timely taken, for both Mason and Smith appeared at the May term of the Superior Court held in Grafton County at which Trustees of Dartmouth College vs. Woodward was docketed. While the principal arguments in the case were deferred until the September term, it appears that Mason at least made a beginning at the May term in Haverhill, for we find Webster, who was not present at this term, writing to Mason in June that "the College people thought you made a strong impression in their cause."

The reputation of both Smith and Mason before the New Hampshire courts made their services in great demand. The case of Dartmouth College was but one of many litigations requiring their attention. To the Trustees and the President, on the other hand, the case transcended all else. One may suspect a slightly lesser degree of personal involvement on the part of Mills Olcott as the Trustees' agent for the suit. After all he was himself a busy lawyer and, though secretary of the Board, he was not a Trustee. Thus his hide was notably more remote from a threat of goring than were those of the President or the Board members. A letter from Brown to Mason in early August leaves it unclear whether the President detected a lack of diligence on the part of Olcott, or whether he was merely demonstrating a common concern among clients lest their counsel neglect their cause for a competing one. Brown assured Mason:

Unnecessarily to intrude, even in a concern deeply interesting to myself and friends, upon a gentleman much engaged in public business has hitherto prevented me from writing you. The agency in the College cause is committed by a vote of the Trustees to Mr. Olcott in whose judgment and zeal we all have certain confidence and I have feared it would not be welcome to you to be occupied by letters from the College officers. An omission to write is not, however, to be construed as evidence either of indifference to the cause at issue or of a want of becoming respect and courtesy to one on whose talents and exertions we rely for its support. This consideration forbids any longer delay.

I can think of no other question, except one which should be related to personal character, on the decision of which consequences depend so important to myself and to the other officers of the College as that for which your services are engaged. In case of a failure we will be cast, either without property or but little, upon the world. Some of us have large and all of us growing families and must seek new spheres of action and new means of support. This is a condition in which we should of course be very reluctant to be placed. Add to this that we regard the services of the Charter Trustees as being essential to the prosperity and usefulness of the Institution, and as deriving still greater importance from its bearing on the stability of all similar literary corporations in our country.

To the Trustees on a recent occasion when I had the offer of an eligible establishment in New York [Hamilton College] I formally proposed the question, in case of my remaining here I must expect them if necessary to prosecute their suit to final decision, though to the Supreme Court of the United States. They promptly and decisively answered in the affirmative. We are not without hope that a favourable decision be given in our Court; though it be otherwise, you may be assured the cause will not be abandoned. I mention this because I have understood that some doubt has been expressed by Judge Smith or yourself whether the Trustees would have the resolution to go forward.

The University, in session since its Board was able to organize in February, elected to hold its first Commencement exercises, in 1817, on the customary date in August long prescribed in the College bylaws. The College, operating of course under the same bylaws, scheduled its Commencement exercises for the same date. On a collision course, each institution asserted its right to use the Meeting House in accord with established practice.

As the day approached rumors of a forcible seizure of the Meeting House by University adherents aroused the students in the College. To forestall any such design, about sixty of the College students and their sympathizers occupied the building, arming themselves with canes and clubs. A counter mobilization of University forces was met determinedly by a heavy guard at each lower window and a battery of stones poised for release at all upper windows and the belfry. The University forces withdrew.

Efforts on the part of President Brown to bring about a compromise by settling on different hours for the respective exercises met with insistence by William Allen that the University have precedence. Those in possession were unwilling to accord it. On Commencement day, seemingly by common consent at the last moment, the College procession moved into the Meeting House at the usual hour of 9 a.m., and the University delayed until 11 o'clock, when its procession marched to the much smaller Chapel in the College yard. Confrontation had been avoided. On that day the College graduated thirty-nine and the University eight.

THE opening of the fall term of the New Hampshire Superior Court at Exeter was scheduled for the following month. The case of the College against the University was set for hearing. Some days before the hearing Webster wrote, on September 4, to Jeremiah Mason in Portsmouth:

Judge Smith has written to me, that I must take some part in the argument of this college question. I have not thought of the subject, nor made the least preparation; I am sure I can do no good, and must, therefore, beg that you and he will follow upon your own manner the blows which have already been so well struck. I am willing to be considered as belonging to the cause and to talk about it, and consult about it, but should do no good by undertaking an argument. If it is not too troublesome ... give me a naked list of the authorities cited by you, and I will look at them before court. I do this that I may be able to understand you and Judge Smith.

When the session opened all three of the College's counsel were present, as were their opponents. The University had retained George Sullivan, New Hampshire Attorney General, and Ichabod Bartlett, Dartmouth 1808, young Portsmouth lawyer and briefly there a local rival of Daniel Webster. Sullivan was a Dartmouth University Overseer and Bartlett one of its Trustees.