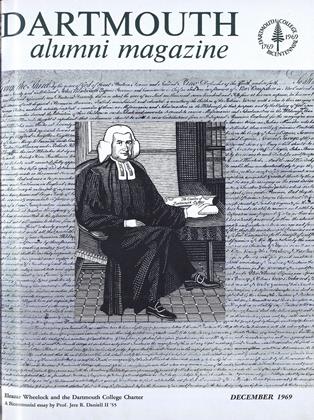

Eleazar Wheelock designated his son John as his successor in accordance with the Charter. At that time John Wheelock was only 25 years old and had neither clerical training nor a scholarly reputation. Fortunately for Dartmouth, however, he possessed the keen business sense necessary to extricate the College from the deplorable financial situation in which he found it.

In spite of the critical state of Dartmouth's finances, a new building was deemed necessary. Construction of College Hall (Dartmouth Hall) was begun in 1784, but because of the scarcity of funds, the building was not completed until 1791. In December 1789 the students, impatient with the progress of the new hall and disgusted with the existing facilities, leveled the old College Hall. This action necessitated also the building of a new College Chapel, which was erected in 1790.

Although this construction put a terrible strain on Dartmouth's finances, John Wheelock had made a sound investment. At the turn of the century, Dartmouth was able to compete favorably with other colleges in attracting students. Two famous graduates of this period were Daniel Webster, 1801, and Sylvanus Thayer, 1807. In 1798 the Medical School was established under Dr. Nathan Smith and was a success from the beginning.

The last fifteen years of John Wheelock's presidency were clouded by the controversy that eventually developed into the Dartmouth College Case. In spite of the service he had done the College in the earlier years of his presidency, by 1815 such an impasse had developed between Wheelock and the Trustees that they removed him from office.

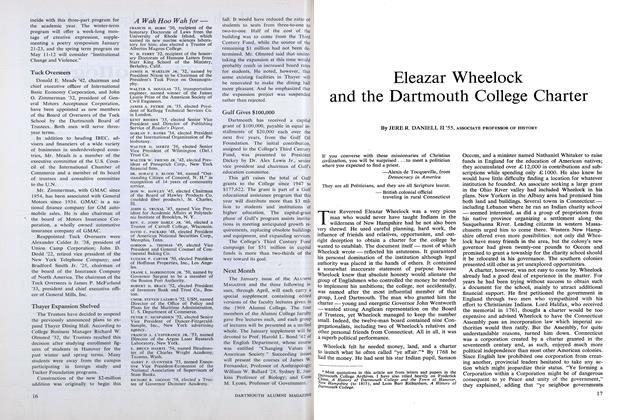

Although Francis Brown was President for only five years, they were the critical years of the Dartmouth College Case. The third President of the College, he was selected by the Trustees to replace John Wheelock. Brown was then only 31 years old, but a highly esteemed pastor in North Yarmouth, Maine. He had earlier spent three years at the College as a tutor.

Soon after he became President, the New Hampshire Legislature amended the College Charter and established Dartmouth University. Brown directed the Trustees' efforts to resist this move in the courts and remained as head of the College, which had been forced into temporary quarters. He took on an extra share of the teaching load as the faculty dwindled, and it is largely to his credit that Dartmouth College continued to graduate such outstanding men as Rufus Choate, 1819.

President Brown also headed the successful drive for funds necessary to continue the court battle. He devoted all his strength and energy to Dartmouth during his presidency, and in a weakened condition, contracted tuberculosis and died in July 1820.

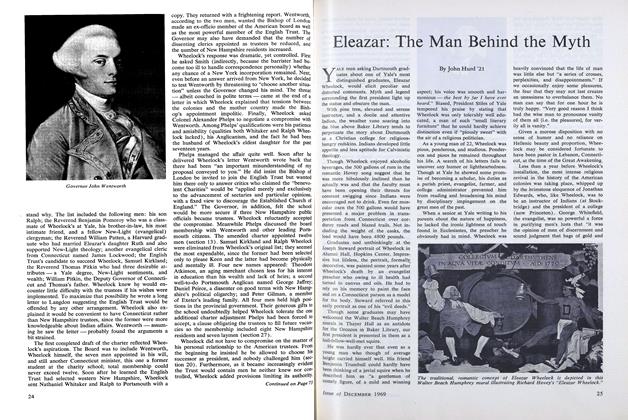

To succeed Francis Brown, the Trustees in August 1820 selected Daniel Dana, a minister in Newburyport, Mass. He was doubtful about taking on the presidency, but finally accepted. As he had feared, the responsibilities of administering the College were too much for him. He resigned in July 1821 and seems to have left no imprint on the College. Later he recovered his health and lived to the age of 88.

When Bennett Tyler, a graduate of Yale, was selected as the fifth President of Dartmouth, he was a minister in South Britain, Conn., and throughout his presidency he tended to regard his pastoral responsibilities toward the students as of primary importance. He took over the duty of preaching in the College Church and left to one of the professors much of the instruction of the senior class, traditionally the President's responsibility. He was rewarded for his efforts by an active religious revival on campus in 1826.

But President Tyler also had to struggle with the very worldly problem of finances. He worked hard to keep the College operating and succeeded in raising the first scholarship fund at Dartmouth. In keeping with his interests, the fund, supported by a public subscription initiated in 1824, was intended for the "education of pious, indigent young men for the ministry."

Student attendance during his administration averaged about 150 men after a decline during the stormy years of the Dartmouth College Case. In 1824, upon the petition of the student body, the first black student, Edward Mitchell, was admitted to the College. He had been brought to Hanover by President Brown.

After six years, President Tyler resigned to return to the ministry. He later was president of the Theological Institution of Connecticut for 24 years.

Nathan Lord, sixth President of the College, served for 35 years, longer than any other president except John Wheelock. A graduate of Bowdoin College, he was a Congregational minister in Amherst, N. H., and a Trustee of the College when chosen President. He was an excellent choice, for he combined an outstanding intellect with a capacity for managing finances as well as men.

He was the first President to deliver a formal inaugural address. It was his belief that Dartmouth should continue the traditional curriculum, with its heavy emphasis on the classics taught by the recitation system, and leave educational innovation to the more "venerable" institutions.

Throughout Lord's years, all activity at the College continued to be influenced by financial considerations. In 1855 President Lord led the establishment of the first alumni association in Boston "with reference to the more effectual raising of money," but this effort failed to produce little more than expressions of concern for the College's financial plight. Nonetheless, funds were secured to erect Went-worth, Thornton, and Reed Halls, although plans to erect a fourth structure to complete Dartmouth Row were abandoned.

Enrollment grew from 125 students in 1828 to 275 students by 1860. Students were drawn largely from the rural sections of New England and were an unruly group. But the President was at his best in dealing with students, who regarded him as a firm but fair disciplinarian.

Even after his pro-slavery views, based on Biblical interpretation, forced his resignation in 1863, President Lord maintained an active interest in the College.

Asa Dodge Smith was an accomplished public speaker with great tact and a kindly manner. He came to Dartmouth from a pastorate in New York City and through his former associations succeeded in greatly increasing the College's endowment. Unfortunately many gifts could not be readily converted into cash, so finding the funds necessary to keep the College operating remained a concern to the President throughout his term.

Only slight changes were made in the curriculum, which remained essentially the same as it had been in Wheelock's day. But for the first time minimum standards of scholastic achievement were set for promotion from one class to the next. President Smith sought to develop Dartmouth into a university, and he welcomed the establishment of the Thayer School of Engineering in 1867. He also urged establishment of New Hampshire's land-grant agricultural college at Dartmouth, and two new buildings were added to house it, Culver Hall in 1871 and Conant Hall in 1874. Bissell Gymnasium was also built during President Smith's administration, and intercollegiate athletic contests date from this period, with baseball first in 1866. Alumni ties to the College grew stronger, especially after the centennial celebration, but all offers of financial support were coupled with calls for reform in the selection of Trustees, who were slow to respond.

Exhausted by the labors of his office, President Smith became seriously ill, and the Trustees reluctantly accepted his resignation effective February 1, 1877. He died the following August.

The administration of Samuel Colcord Bartlett was characterized by almost continuous controversy. With a lack of tact, he alienated the majority of the faculty early in his term, and they requested his removal. The resulting hearings held by the Trustees cleared Bartlett but did nothing to bring harmony to the school.

A profound scholar in the Old Testament, the President, along with a brusque manner, possessed a keen mind and his energy for work was remarkable. During his administration he was most successful in raising the endowment, and most of the gifts were for immediate use. As a result, several buildings date from this period, including Rollins Chapel, Bartlett Hall, and Wilson Hall, erected to serve as the library. He persuaded the students to landscape College Park and build the Bema and Bartlett Tower.

Unlike his predecessor, Bartlett did not regard university development as desirable, and he supported the removal of the state agricultural school to Durham in 1893. He believed strongly in a classical education with little regard for science, so it is surprising that the curriculum revision during his term did begin to reduce the courses required in the classics as well as in mathematics. The variety of subjects offered was increased, and the students were permitted to choose from a limited number of electives.

In 1891 the Trustees, recognizing the need for the financial support of the alumni, finally agreed to permit them to nominate five members of the Board. This development marked the close of a long period of control of the College by conservative members of the Congregational denomination.

President Bartlett felt that this innovation, which he had long opposed, provided an appropriate time for his retirement, and he ended his stormy presidency in June 1892 at the age of 75. He continued to teach courses in the Bible and theology to the seniors for the remaining six years of his life.

The inauguration of William Jewett Tucker in 1893 ushered in a new era in Dartmouth's history. Perceiving changing conditions in American life, President Tucker predicted that greatly increasing numbers of students would soon be seeking higher education. He believed Dartmouth should be ready to serve these young people. Time proved him right: in 1893 enrollment in all parts of the College was 458; in 1909 it totaled 1,233.

He succeeded in his program to transform Dartmouth from an eighteenth-century to a twentieth-century institution because he involved all segments of the greater college community in this development. He persuaded the Trustees that the College should invest its endowment in its own facilities, and during his administration thirteen dormitories were constructed or remodeled from houses acquired by the College. Several academic buildings were also added, and the heating, lighting, and plumbing systems in college buildings were modernized.

He urged the faculty to undertake the much-needed curriculum reform, and progressive changes were made permitting the students more choice in their courses of study. President Tucker felt that Dartmouth was weakest in the social sciences, and he established new professorships in that area. He also noticed that many more graduates were entering business rather than the professions as in the past, and the Amos Tuck School was founded in 1900 as the country's first graduate business school.

President Tucker had a profound influence on the students whom he sought to impress with their duty to use their education in the service of society. He also directed his attention to the alumni of the College and succeeded in bringing them together in a close-knit group for the first time. He de-empha-sized the old plea for financial support, for he believed if he gave them a college to be proud of, donations would automatically follow. The burning of Dartmouth Hall provided the impetus, and funds flowed in for reconstruction of that building in 1906 and completion of Webster Hall in 1907. The alumni thereafter determined to have an annual fund drive.

In 1907 President Tucker developed a heart condition that necessitated his complete retirement two years later. He continued to live in Hanover and died in 1926 at the age of 87.

The Trustees experienced some difficulty in finding a man to succeed President Tucker, but finally Ernest Fox Nichols, Professor of Experimental Physics at Columbia University, was persuaded to accept the position. The first President since John Wheelock who was not a clergyman, Dr. Nichols had taught at the College from 1898 to 1903. His undergraduate work had been done at Kansas Agricultural College, and his graduate study at Cornell.

The progressive development of Dartmouth continued during his administration, but little of special significance is recorded. Three buildings were added to the campus: Alumni Gymnasium, Parkhurst Hall, and Robinson Hall to serve as a student activities center. Perhaps the most significant event was the founding of the Dartmouth Outing Club in 1909 to stimulate interest in outdoor winter sports. Further organization of the alumni resulted in the formation of the Alumni Council to improve communication between the College and its graduates.

President Nichols resigned in 1916 and for the remaining eight years of his life pursued his scientific interests.

Much disapproval was expressed over the selection of Ernest Martin Hopkins as the eleventh President of Dartmouth in 1916, for he came to office from the business world. However, he soon proved that his experience as private secretary to President Tucker, 1901-05, and as Secretary of the College, 1905-10, had prepared him very well for the presidency. He had also spent six successful years in the new field of personnel relations.

The faculty discovered he was as devoted to scholastic excellence as they and came to appreciate his devotion to academic freedom and his interest in promising educational experimentation. The students found he encouraged their participation in the conduct of campus affairs. For example, in 1-924 undergraduates played an important part in the curriculum re-evaluation that resulted in placing increased emphasis on a major subject of study and the development of honors courses.

President Hopkins was especially successful in dealing with the alumni. While working under President Tucker, he had taken an active part in developing alumni organization, and he continued efforts to improve communication with the gradu- ates. One tangible result was a steady increase in financial support of the College.

In spite of the expected low points during the two World Wars and the Great Depression, President Hopkins' administration was a period of growth in numbers of students and faculty, the educational plant, and endowment. The great increase in applicants following World War I necessitated for the first time the adoption in 1921 of a policy of selective admission taking into consideration character, initiative, and broad interests, as well as scholastic ability.

In 1942 at the age of 65, President Hopkins wished to retire, but he was prevailed upon to remain in office through World War 11. He ended his 29-year administration in 1945 and continued to live in Hanover until his death in 1964 at the age of 87.

The administration of President John Sloan Dickey has reflected the growth and change found throughout American higher education following World War II. Under his leadership Dartmouth has developed along purposeful lines to a new high in educational excellence and prestige. It is not yet the time to characterize the Dickey years, but a few of his outstanding accomplishments should be included here to round out the story of the Wheelock Succession.

One of President Dickey's first innovations was the establishment of the Great Issues Course in 1947. Often re-evaluated and revised, it has now become the Senior Symposia. Structurally, the biggest curriculum change came in 1958 with the adoption of the three-term, three-course schedule to encourage independence in learning. President Dickey also presided over the refounding of the Medical School, the opening of the Hopkins Center and the Kiewit Computation Center, and the expansion of graduate study, recognizing Dartmouth's historic university status in everything but name. Throughout he has actively involved the alumni in the development of the College, and they have responded by breaking all previous records of support.

President Dickey has announced his intention to retire during this year, the College's 200th and his 25th as President of the College. The search for President No. 13 is now in progress.

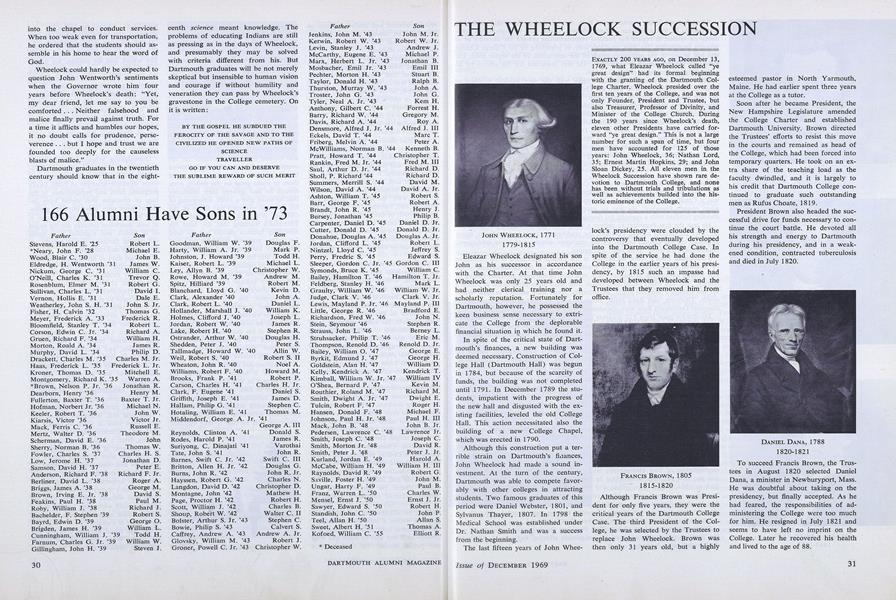

JOHN WHEELOCK, 1771 1779-1815

FRANCIS BROWN, 1805 1815-1820

DANIEL DANA, 1788 1820-1821

BENNETT TYLER 1822-1828

NATHAN LORD 1828-1863

ASA DODGE SMITH, 1830 1863-1877

WILLIAM JEWETT TUCKER, 1861 1893-1909

SAMUEL COLCORD BARTLETT, 1836 1877-1892

ERNEST FOX NICHOLS 1909-1916

ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS '01 1916-1945

JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29 1945-

EXACTLY 200 YEARS AGO, on December 13, 1769, what Eleazar Wheelock called "ye great design" had its formal beginning with the granting of the Dartmouth College Charter. Wheelock presided over the first ten years of the College, and was not only Founder, President and Trustee, but also Treasurer, Professor of Divinity, and Minister of the College Church. During the 190 years since Wheelock's death, eleven other Presidents have carried forward "ye great design." This is not a large number for such a span of time, but four men have accounted for 125 of those years: John Wheelock, 36; Nathan Lord, 35; Ernest Martin Hopkins, 29; and John Sloan Dickey, 25. All eleven men in the Wheelock Succession have shown rare devotion to Dartmouth College, and none has been without trials and tribulations as well as achievements builded into the historic eminence of the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEleazar Wheelock and the Dartmouth College Charter

December 1969 By JERE R. DANIELL II '55, -

Feature

FeatureEleazar: The Man Behind the Myth

December 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureTV News Editor

December 1969 -

Feature

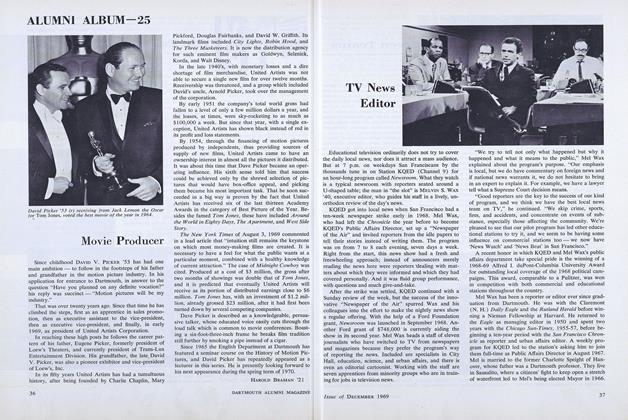

FeatureMovie Producer

December 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

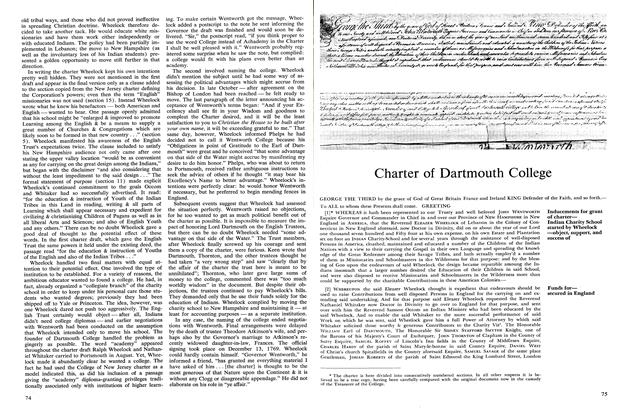

ArticleCharter of Dartmouth College

December 1969 -

Article

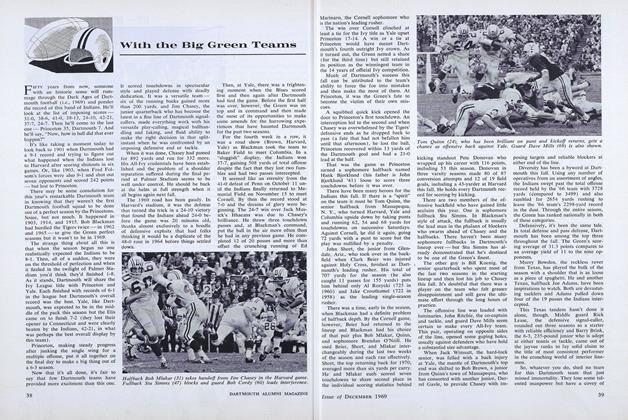

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1969

Features

-

Feature

Feature'59 GETS STARTED

October 1955 -

Feature

FeatureConclave in Cleveland

March 1961 -

Feature

FeatureEnergy: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

April 1974 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCOLLEGE CHARTER

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

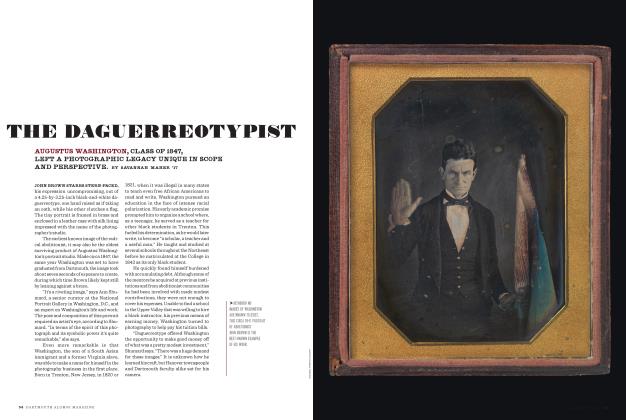

FeatureThe Daguerreotypist

MAY | JUNE 2017 By SAVANNAH MAHER ’17 -

Feature

FeatureBusiness as a Social Service

October 1956 By THE HON. RALPH E. FLANDERS, LL.D. '51, U.S. SENATOR FROM VERMONT