YALE men asking Dartmouth graduates about one of Yale's most distinguished graduates, Eleazar Wheelock, would elicit peculiar and distorted comments. Myth and legend surrounding the first president light up the statue and obscure the man.

With pine tree, elevated and serene instructor, and a docile and attentive Indian, the weather vane soaring into the blue above Baker Library tends to perpetuate the story about Dartmouth as a Christian college for religious-hungry redskins. Indians developed little appetite and less aptitude for Calvinistic theology.

Though Wheelock enjoyed alcoholic beverages, the 500 gallons of rum in the romantic Hovey song suggest that he was more bibulously inclined than he actually was and that the faculty must have been opening their throats for constant swigging since Indians were encouraged not to drink. Even for muscular oxen the 500 gallons would have presented a major problem in transportation from Connecticut over corduroy roads and blazed trails. Not including the weight of the casks, the load would have been 4800 pounds.

Graduates nod unthinkingly at the Joseph Steward portrait of Wheelock in Alumni Hall, Hopkins Center. Impressive but lifeless, the portrait, formally decorative, was painted some years after Wheelock's death by an evangelist preacher who owing to ill health had turned to canvas and oils. He had to rely on his memory to paint the face and on a Connecticut parson as a model for the body. Steward referred to this early portrait as one of his "evil deeds."

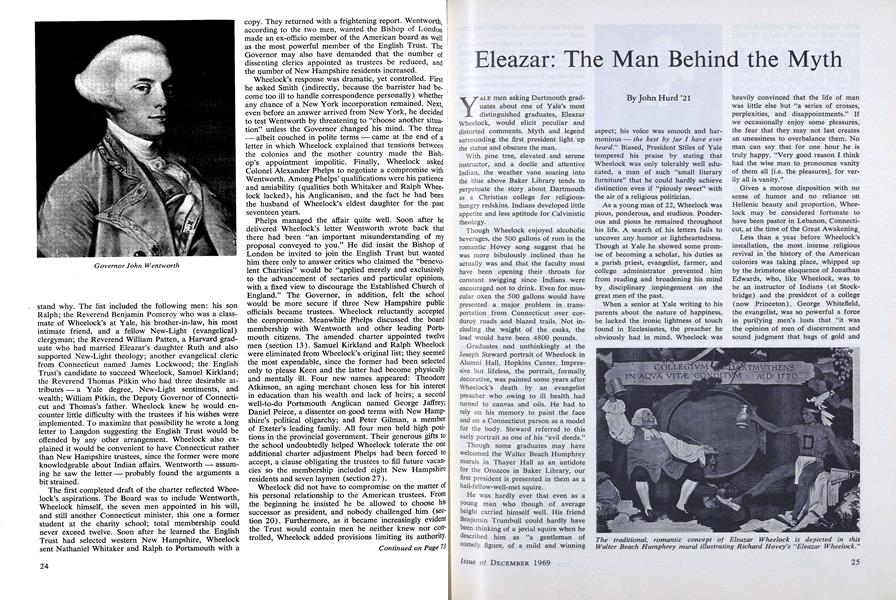

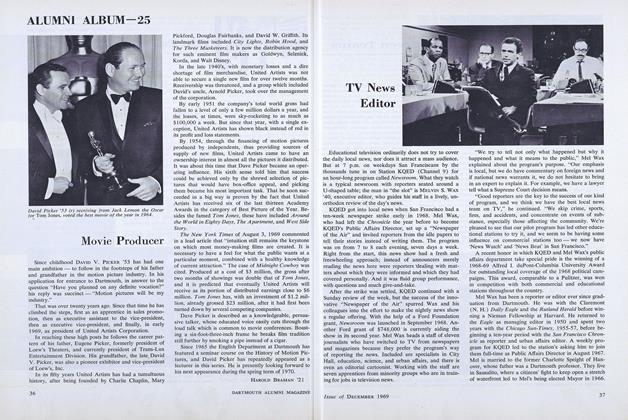

Though some graduates may have welcomed the Walter Beach Humphrey murals in Thayer Hall as an antidote for the Orozcos in Baker Library, our first president is presented in them as a hail-fellow-well-met squire.

He was hardly ever that even as a young man who though of average height carried himself well. His friend Benjamin Trumbull could hardly have been thinking of a jovial squire when he described him as "a gentleman of comely figure, of a mild and winning aspect; his voice was smooth and harmonious - the best by far I have everheard." Biased, President Stiles of Yale tempered his praise by stating that Wheelock was only tolerably well educated, a man of such "small literary furniture" that he could hardly achieve distinction even if "piously sweet" with the air of a religious politician.

As a young man of 22, Wheelock was pious, ponderous, and studious. Ponderous and pious he remained throughout his life. A search of his letters fails to uncover any humor or lightheartedness. Though at Yale he showed some promise of becoming a scholar, his duties as a parish priest, evangelist, farmer, and college administrator prevented him from reading and broadening his mind by disciplinary impingement on the great men of the past.

When a senior at Yale writing to his parents about the nature of happiness, he lacked the ironic lightness of touch found in Ecclesiastes, the preacher he obviously had in mind. Wheelock was heavily convinced that the life of man was little else but "a series of crosses, perplexities, and disappointments." If we occasionally enjoy some pleasures, the fear that they may not last creates an uneasiness to overbalance them. No man can say that for one hour he is truly happy. "Very good reason I think had the wise man to pronounce vanity of them all [i.e. the pleasures], for verily all is vanity."

Given a morose disposition with no sense of humor and no reliance on Hellenic beauty and proportion, Wheelock may be considered fortunate to have been pastor in Lebanon, Connecticut, at the time of the Great Awakening

Less than a year before Wheelock's installation, the most intense religious revival in the history of the American colonies was taking place, whipped up by the brimstone eloquence of Jonathan Edwards, who, like Wheelock, was to be an instructor of Indians (at Stockbridge) and the president of a college (now Princeton). George Whitefield, the evangelist, was so powerful a force in purifying men's lusts that "it was the opinion of men of discernment and sound judgment that bags of gold and silver could have been deposited in the streets with no one wishing to steal them."

The "sins" were so heinous that modern flesh creeps. Three young men and two women were fined for walking the streets on the Lord's Day "upon no religious occasion." A young man was fined five shillings for watching the ice go down the river on the Lord's Day. Swearing was even more serious. A man who said "Damn me" was fined twelve shillings and three pence.

As pastor during the Great Awakening, when a small band of evangelists converted some 25,000 to 50,000 people, Wheelock preached 465 sermons in one year. In Voluntown, Connecticut, he noticed "more of the footsteps of Satan than in any place he had yet been in." It was a gratifying and heartening period for the future president.

As pastor, Wheelock frequently had to play the role of judge in trials often petty, complicated, and time-consuming. He had to adjudicate whether Timothy Hutchinson laughed or smiled during a sermon, whether a man was guilty in not testifying as requested about a case of fornication, whether a Negro girl was such a lying creature that her owner was justified in hating her "like a toad," whether a man accused of intoxication had been imbibing rum or hard cider, whether old Goody Fullsom who had been excommunicated as a witch was hexing her neighbors.

Wheelock took his duties so earnestly that he became dictatorial, and a church council of five ministers assembled in Lebanon to consider eight charges brought against him by his parishioners. He was exonerated.

Wheelock was condemned by Charles Chauncy, a clergyman, for his enthusiasm, the eighteenth-century equivalent of fanaticism. He charged that Wheelock had been led astray at Yale by a Quaker named David Ferris. In a religious club Wheelock and others "laid great stress upon impressions and impulses" and "were strangely unchar- itable, expressing themselves censoriously of most others. They had indeed no opinion of any but themselves on a religious account."

Wheelock delayed sixteen years before writing a long response to such charges and then signed himself "Your unworthy son in the Gospel," but it is doubtful that he believed himself to be unworthy.

Though the Wheelock sermons today seem cold and dull, they took on heat and vivacity in his lifetime because of his agreeable voice, dynamic delivery, and adequate learning. Though not excessive or eccentric himself, he encouraged eccentricity and excess in others. His shortcomings were those of his era. In vain one looks for Christian sweetness and light and finds instead evangelical dogmatism, stress on sin, strident exhortation, intolerant censure, and cruel punishments by an angry God.

Wheelock seems, however, to have been a loving husband and father. As provided for a numerous family, he had financial troubles which embittered him, but he did not show rancor in his home. Aged 24, he married Mrs. Sarah (Davenport) Maltby and so became the stepfather of a son and two daughters. By this marriage he had six other children, three of whom died in infancy.

When his wife died in 1746 (he was 35), he wrote, "She is gone, the dear wife of my bosom, my lover and friend, the desire of my eyes, the dearest enjoyment on earth, the dear partner of all my joys and sorrows, hopes and fears. The most dutiful, compassionate, and tenderhearted and faithful of all women now sleeps in Jesus."

Another woman, Mary Brinsmead, soon sweetened his sorrow, and Wheelock married her. They had five children. So the household now consisted of two stepchildren, three children by his first marriage, his second wife, and five children by her. Other members of his "family" were students whom Wheelock prepared for college, principally Yale, and 15 slaves, some of whom had children.

To the slaves, Wheelock proved a kind and generous master. He gave them a secular and religious education and on occasion was ready to grant one his freedom if he proved competent and law-abiding. Several times in his letters he sends his love not only to members of his immediate family but also to his slaves. To feed so many mouths, he relied on his skill as a farmer.

A MAJOR criterion in assessing Wheelock as a human being would be to examine his attitudes towards Indians for whose spiritual welfare he founded Dartmouth College. Unfortunately the most significant religious gift of white men was a sense of sin, and insofar as the Indians adopted it, the result was disastrous. If they did not, their white benefactors were even more condemnatory. It was too much to ask that the English could sanction one of God's (or Satan's) creatures who paid no heed for the morrow, was cheerful in the face of adversity, never washed, engaged in excessive small talk and grunting, and was so ignorant as not to know that after death a future life offered rewards so exquisite as to be incredible and punishments so cruel as to be unbearable.

Wheelock was more flexible and enlightened than many New England missionaries who were quickly persuaded that Indians were not only not worth saving but also impossible because their souls already belonged to Satan. During King Philip's War, Bostonians maintained that God himself had nicely chosen the redskins and selected their tomahawks to punish New Englanders for failing to persecute sufficiently "false worshippers and especially idolatrous Quakers." Mrs. Mary Pray of Providence was not much out of line when she suggested that the whites exterminate all Indians.

As James Dow McCallum suggests in his invaluable volume, Letters of Eleazar Wheelock's Indians, a reader approaching them may at first chuckle at the misspellings, grotesque idioms, naivete, sense of sin, confessions about courtships, and wrestlings with Satan, With greater acquaintance comes a realization of the profound sincerity underlying the tragedy. Savages were being coerced into studies perpetually and frustratingly remote from American forests and lakes, bows and arrows. From Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, Indians could find so little understanding that they must behave like caged wildlife in reproducing civilized behavior and like parrots in imitating words without fundamental meaning.

Indians were illiterate, slippery, lazy, always gluttonous, and often drunken and consumptive. Wheelock sized them up. "None know, nor can any without experience, well conceive of the difficulty of educating an Indian. They would soon kill themselves with eating and sloth if constant care were not exercised for them at least, the first year. They are used to sit upon the ground, and it is as natural for them as a seat to our children. They are not wont to have any clothes but what they wear, nor will without much pains be brought to take care of any. They are used to a sordid manner of dress and love it as well as our children to be clean. They are not used to any regular government. ... They are used to live from hand to mouth ... and have no care for futurity. They have never been used to the furniture of an English house and do not know but that a wineglass is as strong as an hand iron. Our language when they seem to have got it is not their mother tongue, and they cannot receive nor communicate in that as in their own."

Though on occasion Wheelock would discipline by flogging, he was kind to his Indian pupils. David McClure describes him as the "gentle and affectionate father of his tawny family." But in keeping with the pedagogy of his era, Wheelock had no common sense about how to bring out the best in his Indians. The hours were preposterously long for savages arriving from their forest environment and subjected to the study of Greek, Latin, and even Hebrew and to a highly emotional, not to say neurotic, and soul-probing religion. From sun-up to sun-down, they were forced to occupy themselves with studies of little help in dealing with the environment to which they would return or in teaching their non-Christian brothers to earn livelihoods by manual skills.

None of the Delawares, Mohawks, Oneidas, Montauks, Mohegans, and Narragansets had ever lived in a decent house. Some could speak no English. Some arrived almost naked, and, as Wheelock factually added, "very lousy." They had been accustomed to wandering and to scenes of violence. It is no wonder that they succumbed to tuberculosis, homesickness, carnality, stubborn fits of laziness, and hell-raising. But Wheelock, passionate pedagogue, held stubbornly to his plan of converting the savages to his theological doctrines and assisting them in the enjoyment of the blessedness of salvation here and now.

As Indian father and benefactor, Wheelock won many confidences. The brother-in-law of Samson Occom, David Fowler, an industrious farmer and highly respected among New England Indians, confided in him about Amy Johnson. "I am determined to have Amy for my companion. I shall marry her as soon as I return from Oneida ...

I hope, Sir you will take the best care you can of her. She wants a gown very much, handkerchief also. I wish that you would let her have some fine linen. ... I know that if you love her as much as you do me, all what she desires will be given. It is strange if Mr. Wheelock don't love my Rib as well as my whole body. I have just given her a gold ring, which cost two dollars. I hope, Sir, you won't be displeased with me for that. I think it will do her some good."

Though a persistent' man able to walk 800 miles, alone and on foot, from Oneida country to New England and back (the return 400 miles in less than ten days), he did not marry Amy but Hannah Garret.

The desire to "lie low in the dust" and to "ask forgiveness of God, the Reverend Doctor Wheelock, his family and school" lay deep in the training and hearts of Indians. In Wheelock's handwriting we have the confession of Mary Secuter. "I, Mary Secuter, do with shamefacedness acknowledge that... I was guilty of going to the tavern and tarrying there with much rude and vain company till a very unseasonable time of night where there was dancing and other rude and unseemly conduct and in particular drinking too much spirituous liquor whereby I was exposed to commit many gross sins ... much to the dishonour of God and very prejudicial to the design and reputation of this school and in opposition to the good of my own soul and the soul of my mates, for which I deserved to be turned out of this school and be deprived of all the privileges of it. I desire to lie low in the dust..."

One of Wheelock's pupils had no desire to lie low in the dust. Wheelock describes Samuel Kirkland (1741-1808), the most important Protestant missionary to the Six Nations in the eighteenth century, as one whom he had taken "from the dung-hill and carried - in my arms for seven or eight years." After two years at Moor's Charity School, in 1762 he entered Princeton from which later he received by Wheelock's request a degree in absentia. In 1764 he undertook a mission to the Senecas and later among the Oneidas whom he served for 40 years.

He married Jerusha Bingham, Wheelock's niece "with no dowry other than vital religions and good sense," but in the same year, 1769, the two men became involved in an acrimonious quarrel about money. Wheelock had failed to finance the mission to the Oneidas and Kirkland had accepted financial support from the Society in Scotland and the Boston Board of the New England Company. Despite a meeting in Hanover at which it was agreed that Kirkland was really friendly to the school, that Wheelock had been truly concerned about Kirkland's welfare, and that Satan had been successfully intrusive, Wheelock never recovered from his rancor about his former pupil's "treachery" in allying himself with his benefactor's enemies.

A MAJOR test for Wheelock would be his treatment of an Indian, Samson Occom, who accepted the white man's virtues of cleanliness, frugality, and industry, and raised in England so much money for Dartmouth College that he may justly be regarded as the co-founder. Occom vigorously opposed the foundation of the College, condemned Wheelock's later educational schemes, and denounced the establishment of the College as a perversion of the wishes of the donors.

Though born "a heathen" of parents who "strictly maintained and followed their heathenist ways, customs, and religions," as an Indian lad of 17 he was immediately "convicted" and later sat at Wheelock's feet for four years and studied so hard that he nearly lost his eyesight.

The great moments in Occom's life occurred during his English tour when he preached several hundred sermons in which he appealed intimately to his listeners and exhorted them to consider their souls and their proximity to the grave. Death, sin, and eternity - these were his themes. Even from a snobbish English point of view he was eloquent, ingratiating, and gentlemanly. Otherwise he and Nathaniel Whitaker could hardly have returned from England with the £ 11,000 making possible the founding of Dartmouth College.

But even this best of Indians felt lonely and debarred from the secure and fraternal world of white men. He had to remain a red puppet in the hands of North American whites despite the adulation he received in England, the genuine interest shown him by British aristocrats like the Countess of Huntington, members of the English Trust, and the most distinguished bishops and clergymen in England and Scotland. Wheelock and others could not help patronizing and demeaning him. Not infrequently they reminded him that he was "a brand plucked from the burning."

As Occom matured, he accepted his destiny, bitter and hard. He could not turn white man; he would be a traitor to his race. He must become the conscious champion of his own people, and as such he had to fight the inroads of the new civilization. As one early biographer phrases it, "He became a Moses to a small band of his people, leading them out of the wilderness to die and fall into unmarked graves among a foreign people who in a few decades were to slough off the dominance of a relentless theology."

Wheelock sympathized with Occom about his miserable pay and tried to have it increased. How discriminatory and patronizing the whites were in rewarding him as teacher and missionary may be suggested by his niggardly salary, only £180 for twelve years' work, but they gave £180 to a white missionary for just one year's work.

Without employment, income, arid future, Occom, unable to meet bills for his large family, sank into increasingly degrading poverty which led him unwisely to the bottle. His intemperance and personal tragedy are feelingly described in Samson Occom: The Biography of an Indian Preacher by Harold Blodgett, a volume in the Dartmouth College Manuscript Series.

Concerning the Indian's lapses, Wheelock wrote to the Honorable Trust in England, "Mr. Occom was left last summer to fall a second time into the sin of drunkenness in a public and very aggravated manner. In his drunken fit he got into an affray and fought with a man of the company, and got much bruised and wounded so much that he was confined and concealed in his house for some time."

The gulf between the two men widened when Wheelock moved to Hanover. He was outraged when Occom wrote... your seminary ... is already adorned up too much like the Popish Virgin Mary. She'll be naturally ashamed to suckle the tawnees." Occom spelled out his bitter conviction that Wheelock was spending the money for white students which Occom had collected by his personal effort abroad to further the education of Indians. "I verily thought once that your institution was intended purely for the poor Indians. With this thought I cheerfully ventured my body and soul, left my country, my poor young family, all my friends and relations to sail over the boisterous seas to England to help forward your school, hoping that it may be a lasting benefit to my poor tawny brethren ... I was quite willing to become a gazing stock, yea even a laughing stock in strange countries to promote your cause ... Now I am afraid we shall be deemed liars and deceivers." Nettled, Wheelock attempted to decry Occom's constant desire to play the role of martyr. "My dear man, I think you much dishonour God." He remonstrated with Occom for describing his English tour as "a most tragical scene of persecution." But Wheelock did not answer the charge that the school was now being run for the benefit of white students rather than Indians.

Friction increased. Wheelock wanted Occom to go into the wilderness as a missionary, and Occom did not want to. He wanted to work among his own people, the Mohegans. The two men quarelled over expense accounts.

Wheelock complained to John Thornton that Occom had shown himself to be "exceeding proud and haughty." "He has appeared rather as a dictator and superviser to me in my affairs than as a brother, companion, and helper."

More objective and generous than Wheelock, Thornton championed Occom and arranged that £50 should be paid annually to him. Thornton charged Wheelock with bearing down too hard on Occom. "He is deserving of your tender compassion. He is worthy of your utmost compassion and love."

The breach was too great ever to be bridged. Occom could not or would not accept the invitation to visit Hanover. The last words written in 1774 were Wheelock's, "I have just got to the end of my journey and feel in haste to set my affairs in order to leave them and go to rest. I wish you and those young men may be instrumental to do much for the Redeemer when I am no more."

It is highly ironic that Occom who worked so diligently and brilliantly to help found Dartmouth College should never have seen it though he lived to the age of 69 and did not die until 1792, 13 years after Wheelock.

IN the Steward portrait of Wheelock, the white wig puffed out over the ears, the black gown covering a comfortable corpulence, the fleshy face and double chin, the left hand grasping a manuscript, and. the comfortable black buckle shoes may suggest the possibility of a happy retirement.

But no. John Dickey to the contrary notwithstanding, college administration ages prematurely even the most stalwart of males. The elderly Wheelock is perhaps best painted by his physician who, aware of the educator's "cuticular eruptions," said, "You are of a plethoric habit of body, have a great fulness of blood and humours, a very weak, broken, relaxed, and unelastic system of nerves." The doctor advised him to avoid salt meat and to wear a root at the pit of his stomach.

But Wheelock could not afford fresh meat and wine. He had spent most of his capital, had been granted no pension, and was so miserably poor that he was unable, so he wrote, to buy a cask of wine or spirits or coffee or chocolate or tea though his physicians all urged him strongly to fortify his ailing body. Death ended his miseries in 1779, nine days before his 68th birthday.

In a final estimate Wheelock may be measured as clergyman, teacher, family man, fund-raiser, and president. As clergyman and teacher he exercised absolute authority. It was his mission, as he himself said, first to Christianize the heathen by forming their minds in accordance with "the rules of religion and virtue"; and, second, to educate the "pious youth of the English to bear the Redeemer's name among them in the wilderness" and to choose "meet persons for the sacred work of the ministry in the Church of Christ among the English."

Most students submitted cheerfully to the puritanical regime in which all "vain, idle, trifling, and flesh-pleasing" pleasures were rigidly excluded. David McClure, Wheelock's confidential clerk and a close friend, describes Wheelock's government as "parental." "No father watches over his rising offspring with more tenderness . Neither unfeeling authority nor unnecessary force ever alienated the affections or hardened the heart of his pupils ... Those under his care obeyed from affection and respect . . . Yet when circumstances demanded it, he appeared in majesty and awed the offender into obedience."

To maintain good order and regularity among students, Wheelock believed that he had only to show them what is the law and mind of Christ and what would please God and what would not. In brief, please God, please Wheelock.

Frederick Chase in his History ofDartmouth College remarks that Wheelock "possessed shrewd business capac- ity and executive talent of the highest order." He did indeed show it in his family affairs. He and his sons and daughters gained control of almost all of Hanover. Given 200 acres by the College, he acquired another 800, most of them within a mile of the College. On Wheelock land stood not only the College itself but also its mills and malt and potash houses. To his four sons Wheelock parceled out 200 acres each and 100 to his two resident daughters. Thus all six members with farms in the immediate vicinity of the College were established in an almost feudal family dynasty. If the family had survived and continued to prosper, the history of the College and Hanover might have been different.

James Dow McCallum in his life of Wheelock points up Wheelock's inability to view the College and himself objectively in financial matters. Personal and academic expenses became so blurred that Wheelock overdrew the £9000 of his English Fund by £500 and blamed the English trustees for the overdraughts because they had allowed him to exceed the total. He expected them to make good on the deficit, even though he had ignored their insistence that he must give a strict accounting of his personal expenses and those of the College. Wheelock also ignored John Thornton's warning that the fund for educating Indians should not be used for college purposes and with his usual generosity had permitted Wheelock to draw on him for £5000.

At the beginning of the Revolution Wheelock found himself deeply in debt with twenty Indians and ten white students on charity. He had no money for their support, his four tutors in the college, and a schoolmaster. With all his heart he wished that the £. 1000 owed him could be collected, but he told his agent that if his debtors were hard up, they should not be further distressed. The agent should take only "what Christ would receive at their hands."

The virtues and defects that Wheelock showed as a teacher controlling his pupils appear in Wheelock as president. He tended to look on his trustees, faculty, and subordinates as fractious children, wayward adolescents, or adults perversely influenced by the Devil. So autocratic was he that if they opposed him even in petty trivialities he was censorious to the point of vindictiveness. Anyone who questioned his point of view was an enemy of Jesus Christ. The school and the college, his consecrated edifice, were built with his own hands and enriched by his mind given direction and wisdom by God. Dedicated to the verge of fanaticism, Wheelock increasingly sought power not to better himself financially or to be revered as a minor deity but only because power could enable him more quickly and efficaciously to spread the teachings of Christianity in a sinful world.

Outweighing Wheelock's defects are undeniable virtues: unswerving devotion to what Wheelock believed was truth, dynamic attempts to fulfill God's purposes, faith and perseverance in the face of obstacles that would have defeated lesser men, quiet but firm gentleness in dealing with Indians, spartan if at time querulous courage during sieges of ill health, and dignified if at times self-pitying fortitude during attacks on his integrity and character.

The last days of his life were so filled with adversity that even had he been healthy he could have hardly risen to the plateau of the jolly squire of the Walter Humphrey mural. The charity students were so poor that he had to cut up sheets, table cloths, and towels from his house to cover their nakedness. The bitter winter of 1778-79 killed many of his livestock. (In 1774 a student smuggled out some bread to exhibit it in Portsmouth, and in consequence Governor Wentworth questioned Wheelock in "the strict duty of friendship" whether college food was so skimpy and so substandard that students became "thereby unhealthy and debilitated, their constitution impaired, and their friends and parents highly disgusted.")

Sick and old, Wheelock feared that evil forces were at work to negate his work of a lifetime. He suffered from asthma, from a cutaneous eruption, and in the last year of his life from epilepsy. A little less than a month before his death, he described himself as being "in a very low state" and that his case was "esteemed desperate by his physicians," but by God's mercy he had so far revived that without other help than his cane he could walk from his bed to his fire and back again and even to sit up for a while in a chair.

Old age could kill the man but not his spirit. When he could no longer walk, he ordered that he be carried into the chapel to conduct services. When too weak even for transportation, he ordered that the students should assemble in his home to hear the word of God.

Wheelock could hardly be expected to question John Wentworth's sentiments when the Governor wrote him four years before Wheelock's death: "Yet, my dear friend, let me say to you be comforted .. . Neither falsehood and malice finally prevail against truth. For a time it afflicts and humbles our hopes, it no doubt calls for prudence, perseverence . . . but I hope and trust we are founded too deeply for the causeless blasts of malice."

Dartmouth graduates in the twentieth century should know that in the eighteenth science meant knowledge. The problems of educating Indians are still as pressing as in the days of Wheelock, and presumably they may be solved with criteria different from his. But Dartmouth graduates will be not merely skeptical but insensible to human vision and courage if without humility and veneration they can pass by Wheelock's gravestone in the College cemetery. On it is written:

BY THE GOSPEL HE SUBDUED THEFEROCITY OF THE SAVAGE AND TO THECIVILIZED HE OPENED NEW PATHS OFSCIENCETRAVELLERGO IF YOU CAN AND DESERVETHE SUBLIME REWARD OF SUCH MERIT

The traditional, romantic concept of Eleazar Wheelock is depicted in thisWalter Beach Humphrey mural illustrating Richard Hovey's "Eleazar Wheelock."

Eleazar Wheelock in the portrait thatJoseph Steward painted from memory.

Wheelock's first teaching days in Hanover as imagined in an 1839 engraving.

Samson Occom, by Adna Tenney.

Baker Library's weathervane legend.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEleazar Wheelock and the Dartmouth College Charter

December 1969 By JERE R. DANIELL II '55, -

Feature

FeatureTHE WHEELOCK SUCCESSION

December 1969 -

Feature

FeatureTV News Editor

December 1969 -

Feature

FeatureMovie Producer

December 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

ArticleCharter of Dartmouth College

December 1969 -

Article

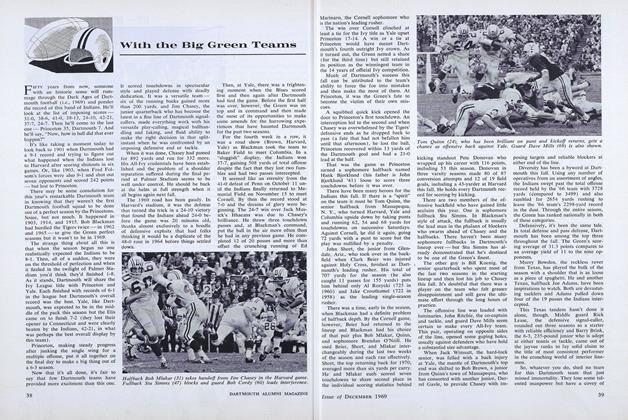

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1969

John Hurd '21

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

December 1975 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN, THOMAS W. STALEY, JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleSIGHTED and SUNK

February 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleHe Values the Rare In Books and Life

May 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksEGYPTIAN ASTRONOMICAL TEXTS: III DECANS, PLANETS, CONSTELLATIONS AND ZODIACS

JUNE 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksFurther Mention

JANUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

JULY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWHEELOCK’S CONCH SHELL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

MARCH 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Features

Features“A Fierce Advocate”

MAY | JUNE 2025 By GRACE BROWNE -

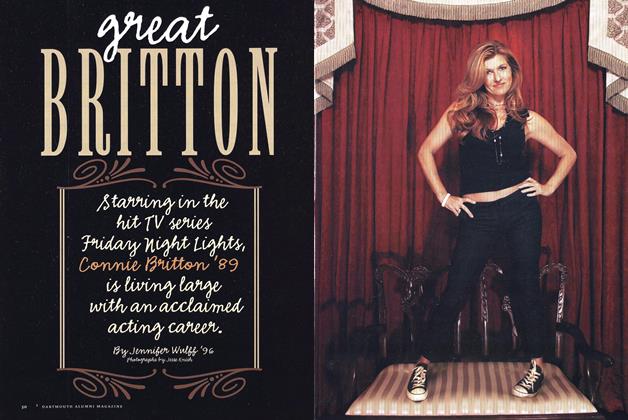

Feature

FeatureGreat Britton

Mar/Apr 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

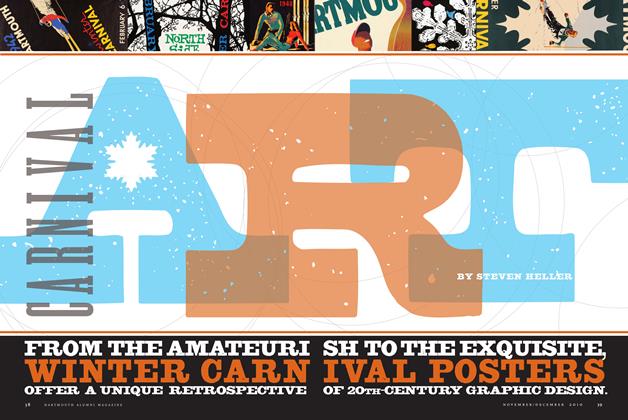

FeatureCarnival Art

Nov/Dec 2010 By STEVEN HELLER -

Feature

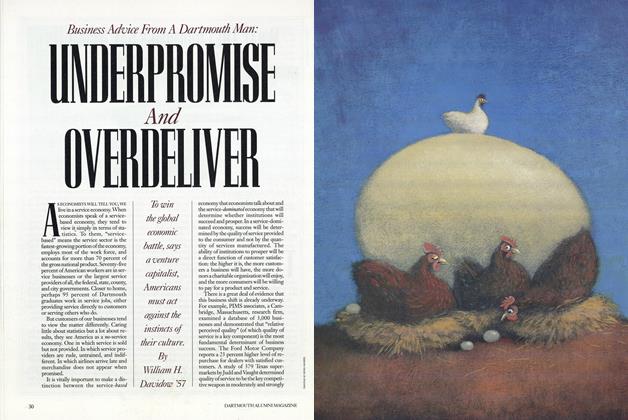

FeatureUNDERPROMISE AND OVERDELIVER

OCTOBER 1990 By William H. Davidow '57