I wrote this talk in Baker Library, where I could watch as carpenters and painters prepared this platform. And I felt much like a condemned man looking on while his scaffold is built, for fresh in my mind was last year's speech by James W. Newton, valedictory speaker of the Class of 1968. I remember with sorrow that an extremely bright and even more concerned Dartmouth senior should feel compelled to denounce his country in such scathing terms. And I remember with horror the vilification to which he was subjected.

At the ceremony and for months afterward, this valedictory speaker, this Quaker, was cursed, ridiculed, and threatened by fellow Dartmouth alumni.

At this pivotal moment in this college's long history and in the evolution of the American university, to sacrifice the precious value of free speech is to deny the power of knowledge and the purpose of Dartmouth.

In the light of Jamie's speech and the recent illegal seizure of Parkhurst Hall, I should like to clarify what I regard to be some of the sources of the nationwide student discontent of which we all are increasingly aware.

I speak as a member, and not a representative, of the Class of 1969.

When most of that class was 6 or 7 years old, the Supreme Court-ordered the desegregation of public schools. When baseball meant more to us than anything else, Little Rock was an occupied city. Fifteen years - three-quarters of our lives - later, schools in North and South remain segregated, separate and unequal.

When we were in junior high school, we read George Washington's Farewell Address. Our first President said: "The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is to have with them as little political connection as possible." He warned against entangling alliances in terms so definite that they now might be called neo-isolationist. But soon we saw that our country supports corrupt and unrepresentative regimes in Latin America, in Africa, and in Asia, that it cabals against Castro but rewards Franco.

In the last several years we have risen to stirring challenges posed by three extraordinary leaders, only to see them become three murdered men.

As Dartmouth students, though blessed with loving parents and comfortable homes, though passing through as idyllic a college education as money can buy, we have felt with real intensity how much suffering is inflicted in this land of plenty.

White liberals, middle-class, and mid-dle-of-the-road, we have crouched in the shadow of the draft as a war drags on, remote, expensive and interminable. We have seen that though its cities burn, this nation continues to spend billions to build missiles and bombs, instruments of death.

No college could be unaffected by this inversion of the American dream of a beer at the ballpark or the fraternity house, a situation comedy on the tube or on a road-trip.

Dartmouth has had painful confrontations.

I remember with horror how the personal safety of a visitor to this campus was threatened in the riot following George Wallace's speech here two years ago. But just as frightening is that fact that this campus could insult its black constituents by inviting here an unmitigated racist, a man who had to be an unconscionable symbol of oppression and hatred with which to confront a dignified and responsible Afro-American Society.

Last month, a few students saw fit to remove forcibly from their offices the administrators of this college. This type of pitifully misguided action must be punished firmly. Learning ceases when the integrity of procedure is flouted. The President of Dartmouth College shall not be manhandled by would-be martyrs, anachronistic Trotskyites.

But Parkhurst mutely witnessed another horror. That bleak morning, as riothelmeted police drove onto the Dartmouth campus, students cheered, as if at a football game. Eager for a carnival of bloodshed, beery and raucous, they chortled as the College on the Hill was overrun by state troopers. These officers had to show commendable restraint because as they arrested 56 frightened young people, other Dartmouth students begged to see their fellows beaten.

In response to this sad chronicle, I wish I knew how we could return to our business here, learning. By inclination and education, I am unequipped to defend so-called student rebels here or anywhere. The moralistic intolerance they preach, their heady intransigence, is unacceptable. Their weapon of terror has no place in a society which, for all its abuses, is still free.

The idealism of youth cannot justify its myopia. Plutarch wrote: "The boys throw stones at frogs in sport, yet the frogs do not die in sport, but in earnest." We all need to realize that violent defiance of the law here at Dartmouth will not bring our brothers home safely from Vietnam. It will only jeopardize the freedom and security of the university in a system which will survive after Vietnam.

The college should be an enclave, the safest refuge of the dissenter. Civil discourse must proceed without any hindrance, whether it be shouting obscenities at President Dickey or at a valedictory speaker. Free speech must be inviolable; the terrorism of the self-righteous must cease; or else the colleges, not the society or its inequities, will be destroyed.

We must recognize that the blind alleys of partisan polemics are incompatible with the expanding vistas of a liberal education. I hope that the Class of '69 has learned that in politics there is no right, only shades of error and kinds of guilt.

While we must preserve the conditions on which civilized society and academic freedom depend, we cannot deny the reality or the magnitude of the causes of students' frustration, causes which demand the compassion of a wise and just community.

Racism persists. Americans in Appalachia or Harlem or New Hampshire remain ill-fed and ill-clothed. Arbitrary and painful conscription continues. And the war goes on.

You must understand that we have no small worries, and as we read news magazines and watch television, these broken promises have become personal matters to us. Our contemporaries die in Southeast Asia, and the draft poisons our future, while the tragic waste of natural and human resources worsens. Prophets of hope, the few politicians who retain and respect the conscience of youth, are extinguished one after another, almost predictably. The problems of America the superpower are finally right up close where we can see them in stark and ugly relief. So we writhe in an unwelcome harness of guilt.

At this college, thousands coexist with little common purpose. We are bewildered as popular teachers are fired, as the faculty consults student opinion on ROTC, but not on the Afro-American Society demands, and makes decisions binding on the community at meetings closed even to the press.

We are confused by an administration which seeks injunctions but ignores the dangerous illegal possession and consumption of alcoholic beverages by minors and of narcotics. And we are told to respect the law.

As the frustrations produced by these and other factors cause periodic explosions, anyone devoted to this institution and this country must be concerned. I wish to remind you only that however dangerous their tactics of confrontation, however long their hair or Marxist their rhetoric, they are still your children, trying to talk to you. In this fellowship without parting, they are still sons of Dartmouth.

How can we reach them?

Not by compromising free speech to reduce the costs of ethical individuality. Some local gentlemen have begun proclaiming, "Love Dartmouth or Leave It." If faced with that choice, I would leave, not because I did not love Dartmouth but because I did.

Not by investing and discarding a dean and a judiciary system every year, or by adding to a burgeoning bureaucratic structure which in fact prevents the faculty from effectively guiding the College.

Not by expanding in every direction, by attempting to become an elitist parody of the American megalopolis. Suddenly, after 200 years, Dartmouth need not adopt the battered soul of the American multiversity, only clothing it in the psychedelic colors of graduate education, an urban campus, and coeducation. Such gross institutional changes must be given more patient evaluation.

Before peace can truly be restored here or on any campus, this country must extricate itself from the Vietnamese conflagration and change or discard the draft system which, as Governor Rockefeller said a year ago, "keeps a man in a needless state of suspension for eight years of his life."

We must reduce the gap between will and action, between a vote and its effects, and at the same time we must resist the incursions on our privacy made by undirected big government and mass society.

At Dartmouth, this means we must calmly reconsider the College's connections with the United States Government and decide which, if any, must be severed. The criterion of judgment should be less whether Dartmouth helps carry out moral decisions than whether it can participate in the decision-making process.

No progress will be made without attention to the responsibilities of every member of this community. We need desperately to respect each other again. We must proceed without personal or generational rancor. We must regard others, in George Eliot's words, as "equivalent centers of being."

We cannot napalm ideology. We can not use the principle of individual freedom to perpetuate racial discrimination. On a smaller scale, we must not assume that ends sanctify means by forcing our ideals on the community. To protest a war by paralyzing a college or to foment crises which inhibit the long-range solution of problems is counterproductive.

If we must be politicians, let us gauge the risks of our political actions. Let us place our tactics as well as our ideas in a societal context and a historical perspective. To disrupt the academic process is to encourage not revolution or reform but repression.

As a college, Dartmouth must after 200 years define itself as an institution. It must clarify the manner in which it shall be governed. Without sacrificing its diversity, it must seek certain common institutional values, beginning in freedom of enquiry.

This college, like this country, has a great absorptive capacity. The present society-wide aroma of alienation shall pass.

But we must learn from the Parkhurst occupation and the bust what we failed to learn before: That momentum alone does not protect a college. That we must listen and respond to justifiably frustrated, sincere, tremendously caring young men.

Only then can the famous ideals of youth become the goals of a just society. Only then can this college again be as serene and as open and as majestic as its surroundings.

Valedictorian Kenneth I. Paul '69 ofForest Hills, N. Y., held top honorsamong 32 summa cum laude graduates.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

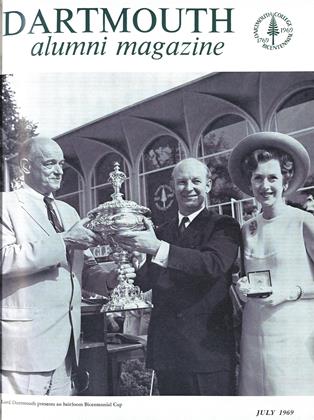

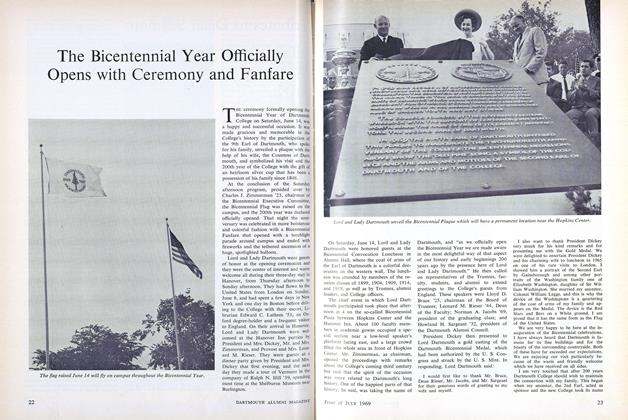

FeatureThe Bicentennial Year Officially Opens with Ceremony and Fanfare

July 1969 -

Feature

FeatureThe 50-Year Address

July 1969 By DR. ROBERT M. STECHER '19 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1969

July 1969 -

Feature

FeatureA New Investment Concept: Total Return

July 1969 By JOHN F. MECK '33 -

Feature

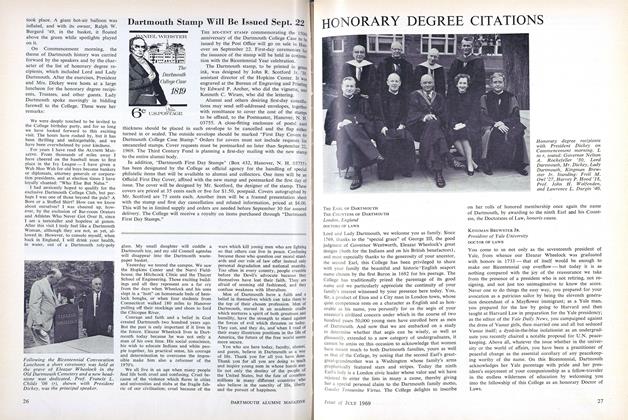

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1969 -

Feature

FeatureTimbers Heads Alumni Council

July 1969

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSidney Chandler Hayward '26

JULY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureImpacts simply positive

MAY 1982 -

Feature

FeatureClass Notes

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Feature

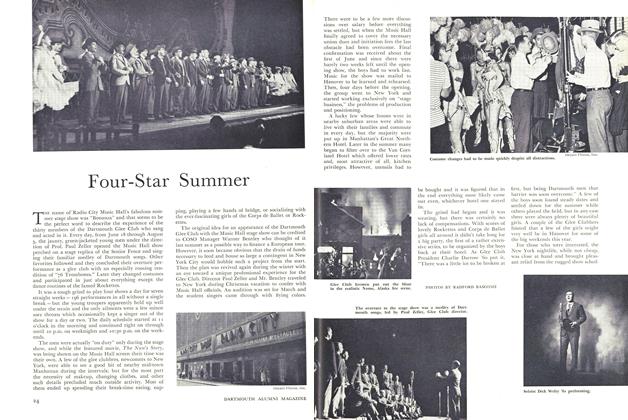

FeatureFour-Star Summer

October 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureADMISSIONS—SCHOLARSHIPS—ENROLLMENT

April 1954 By Robert L. Allen '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWelcoming the Loner

SEPTEMBER 1988 By Victor F. Zonana '75