Mud, Madras and Madness!

One alum shares her humorous take on the early days of coeducation.

July/August 2005 Gina Barreca ’79One alum shares her humorous take on the early days of coeducation.

July/August 2005 Gina Barreca ’79The minute I SaW my new book Babes in Boyland: A PersonalHistory of Co-education in the Ivy League between hard covers, I knew I should have done it all differently.

I'd always wanted to write something about those days because of all the bizarre, funny, wonderful, awful stuff that actually happened. I thought about doing the book as a novel, but realized the best lines were lifted from reality: students in need of contraceptives having to get them from Dicks House, for example. You can't invent that kind of story.

What's the book about? Think Thelma & Louise attend AnimalHouse. Then reframe Thelma and Louise as a bunch of 18-year-old girls lacking the wisdom and panache—and firearms—of the screen horoines, and you've got the concept behind this very personal memoir of my time in Hanover during the early years of coeducation.

What is the book not about? It's not an overview of the forces behind the move toward coeducation. Nor is it an objective account of a certain moment in the history of Dartmouth. Although I am now a college professor, I decided I wasn't the one to provide a socio-political, academic-y version of coeducation in the Ivy League.

Babes doesn't say all it should.

And it says way too much about sex.

It says a little bit about how kids feel when they apply to college, especially when they are the first ones in their families to do so. I was prepared academically for Dartmouth by my huge public school on Long Island, New York. In no other respect, however, was I ready. For my first semester I bought black leather boots and told everybody they were to protect me against the elements, even though I secretly hoped I'd wear them only to glamorous parties; on a good day, they made me look like Morticia Addams. Then there was a brown pinstriped three-piece suit. I thought the slit-skirt and tight vest made me look chic. I thought it would help me fit in. It didn't.

My idea of "college girls" came from old copies of McCall's and Look my grandmother kept around her house. Going to New Hampshire to be a "coed" was like going back in time.

I surely felt I was in another century, or a parallel universe, when a girl from my dorm explained that her grandmother was giving her a coming-out party. I said, "Wow, you've got some hip grandmother. I didn't even know you were a lesbian." We stood in the hallway looking at each other, having no clue whatsoever what the other meant.

Babes deals a whole lot with the differences not only between men and women at Dartmouth, but between working-class students and the students from more financially privileged families Some of us took the Greyhound bus to White River and then begged rides to campus from those not-too-drunk-to-drive coleageus having eggs at the Tally House.

In contrast, several students arrived in Hanover in a coach and six with liveried footmen in attendance—or so I believed. They then lived in dorms named after their great-uncle or maternal grandfather.

Writing in DAM about being a working-class kid at Dartmouth has always generated marvelous responses from alums who came to Hanover feeling the same way in 1937,1946,1951 and even 1974. My experience was slightly different from theirs, however, because the establishment had admitted women as matriculating students only three years previously. (When I explained this to one of my aunts, she looked embarrassed, as if "matriculation" was like incontinence or menopause and not to be spoken of in mixed company.)

Diversification was on the Colleges agenda in the early 1970s perhaps because an enlightened trustee woke up one morning and declared, "Hey, there are all these other students who might make the College stronger, better and more interesting—let's admit girls." Maybe President Kemeny had something to do with putting forth the persuasive idea that Dartmouth's voice should be part of the future rather than a mere echo of an increasingly distant past.

While there was an awareness of the homogeneity of the group overall, and a desire to make the joint less like a squash club, let's just say there were not-a lot of ethnic types around. At least it did not seem that way to me. Simply by being short and dark, with brown eyes and curly hair, and being the first one in my family to attend college, I felt like an insurgent, an interloper, a new kid, the most unlikely of freshmen.

I should have mentioned the night a fire alarm rang through the dorm and we all huddled outside in the freezing cold in our Tshirts—almost all of us. One girl was (and still is) a world-class sleeper. Olympian. She lived in a single. Waking to some kind of sound she couldn't identify, she wandered out into the hallway and saw that doors were open but that nobody was around. Naturally, she started to cry. Not because everyone in the dorm basically left her to die, but because when she saw the doors open, she assumed there was a great party someplace and she hadn't been invited.

That's pretty much how a lot of us felt: "There's a party going on someplace. Everybody else is there, and I'm here trying to figure out how to find my way." This friend just literalized it.

I should have talked in Babes about the girls who would come for the weekend from other colleges wearing so much makeup they looked as if they'd been prepared by a taxidermist. We never knew how to treat these other young women: Were they rivals, colleagues, peers, potential friends, sisters or enemies? Were we all in it together or were they poaching on our territory?

I'd also never seen teenage boys wear pink, yellow and limegreen clothes; madras had not been part of my life in Brooklyn. At home it was even rare to see guys in shorts, for that matter—cutoffs, yes, bare-chested for better or worse at the beach or washing the car, with sneakers and no socks. But these boys were wearing shorts that obviously started life as shorts. Amazing.

I didn't mention that at any moment on campus, there was some guy somewhere playing the opening chords of "Smoke on the Water."

I deliberately left out any mention in Babes of my experience on a Freshman Trip because Brenda Gross '79 wrote a piece for this magazine ("Who the Hell is Lucifer," June 1996) so entirely perfect that anything I might have added would have been redundantnot that we were on the same trip, you understand, but she could well have been. Let's just say that Brenda and I were equally outdoorsy, meaning that we brought mascara and hairdryers for our hikes up Moosilauke but neglected to bring heavy socks or potable water. ("Potable" not being a word I heard very often while growing up.) Brenda summed up the Freshman Trip quite neatly when she confessed she should have chosen a less-demanding ex- perience: "I overreached. I needed the artsy-Jewish-girl-who-never- really-exercised module. The one where you walk to Friendly s and get a shake."

How about the mud bowl? I remember watching a cute boy who was holding a bottle of beer in one hand and a garden hose in the other to flood the already sodden pit of mud behind his fraternity house. "Ramblin' Man" was playing on loud speakers turned to face outward from inside one house, music that competed with the Bruce Springsteen coming out of another. "I Feel Good" by James Brown emanating from the Afro-Am house rounded it all out. It was all happening right around the Choates. It seemed exciting, the air heavy with smells of beer, barbecue, popcorn, boy-sweat and beer.

Then everything happened at once. I didn't see or hear a signal but as fast and total as a kaleidoscope changes image, there was a shift of colors, sounds and patterns. Awhoop like a war cry went up as boys started running. Toward girls. I had no idea what was going on. They started picking up girls—any girls, all girls—and throwing them into the mud. I went to my room in Brown Hall, locked the door behind me and miserably wondered what was wrong with me. Why didn't I understand this kind of fun? I wanted to. Only later did I learn to trust the instinct that said, "You don't want to tell your daughters you met their father when he threw you into a pit."

You don't want to tell that to your sons, either.

As I look through the final version of Babes, everything inside the book seems suddenly wrong. Unbalanced. Heartbreakingly incomplete. I should have written more about what I loved: working at the writing center; the northern lights as I'd never seen them, brighter than Coney Island, brighter than the Chrysler Building. They took up the whole sky one night in the fall of 1975.

When I left Hanover for a study-abroad trip to London in the fall of 1977, my friend Pam Katz 'BO scribbled a note that I have kept, one way or another, for close to 30 years—a small triangle of paper folded into my handbag. It reads, "When you get there, wherever it is, save a place for me."

Pam and my other friends—both male and female—sustained me. They were the best part of my experience at Dartmouth.

The best days were the ones where we somehow, affectionately, bizarrely, unexpectedly looked after one another, trusting that laughing out loud was a way of making our own voices ring clear through that wilderness.

So I should have talked about how, even though I was a recovering Catholic, I would accompany my friend Nancy Lager '79 to the service for Yom Kippur every year. The rabbi would intone a line about offering forgiveness to the "stranger in our midst" and I always wanted to put my hand up and wave, shouting "That's me! That's me!" But I didn't do that because if I had, Nancy would have had to confess during the next year's high holidays that she had killed her roommate.

And I should have mentioned my favorite document from college—forget diplomas or formal photographs. Hand-drawn with colored Flair pens by Natalie Jensen '79, it offered the following promise before a dreaded exam: "Aujourd'hui, mes petites filles, we shall turn our attention to the subject of French. First of all, French is for French bread, as all gourmands know. French is also for French poodle, a type of animal of the species usually referred to by the recipient as 'doggos.' There is also a kind of kiss, or so we have been told, but we say no more. Lastly, there is the use of the term French as in 'French exam,' and we are not referring to the baccalaureate. It is in this connotation that we wish to reassure the recipient of the harmlessness, simplicity and unimportance of the French exam. This card is an official, USDA inspected, GOOD LUCK CHARM, which cannot fail to bring satisfactory results when used before December 31, 1975, or your money back." With a flourish, she ended the card with "Liberte, Egalite, Sororite."

We sailed into our futures under that banner, sheltered under that aegis.

We did better than we could have imagined.

I didn't mention that at any moment on campus playing the there was some guy somewhere opening chords of "Smoke on the Water."

GINA BARRECA is a professor of English literature at the University ofConnecticut and a columnist for the Hartford Courant Her book Babes in Boyland (University Press of New England) was published in April.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

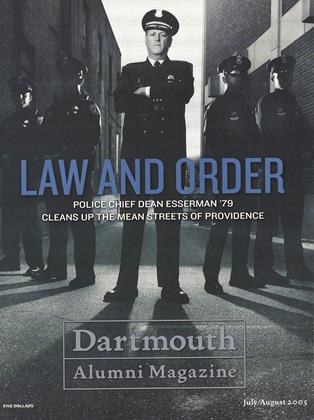

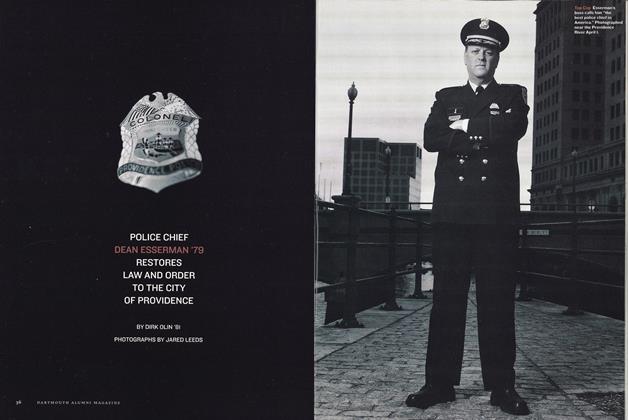

Cover Story

Cover StoryPolice Chief Dean Esserman ’79 Restores Law and Order to the City of Providence

July | August 2005 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

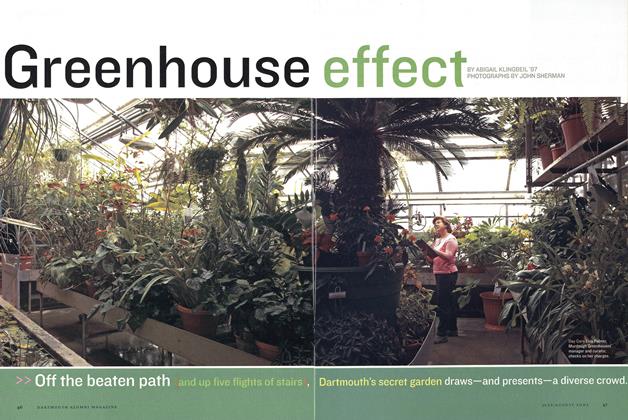

Feature

FeatureGreenhouse Effect

July | August 2005 By ABIGAIL KLINGBEIL ’97 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2005 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2005 By Thomas Vieth '80 -

FACULTY

FACULTYLearning Curve

July | August 2005 By James Heffernan -

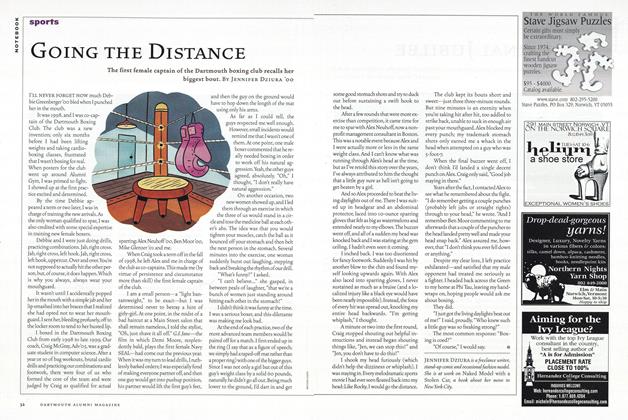

Sports

SportsGoing the Distance

July | August 2005 By Jennifer Dziura ’00

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHanover's Bests

DECEMBER 1984 -

Feature

FeatureSMITH

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1951 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureThe Day I Got Chewed Out By Red Blaik

NOVEMBER 1989 By Rodger S. Harrison '39 -

Feature

FeatureThe Medical Legacy of August 1945

December 1979 By Stuart C. Finch -

Feature

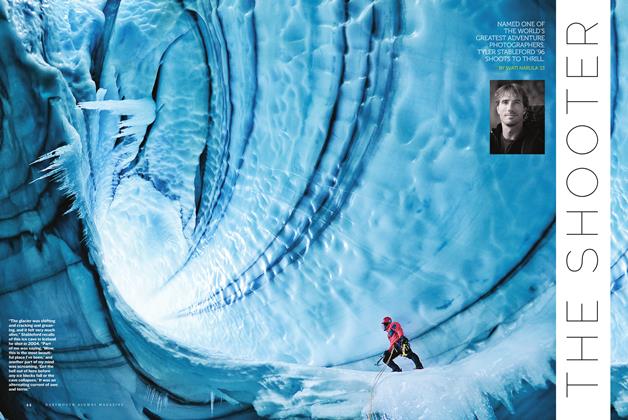

FeatureThe Shooter

Jan/Feb 2013 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13