By Douglas L. Wheeler '59 andRené Pélissier. London: Pall Mall Press,1971. 296 pp. £3.75.

The latest addition to the Pall Mall Library of African Affairs, this book is divided into three parts, two of which, written by Douglas Wheeler of the University of New Hampshire, are dedicated to the memory of Richard Blaine McCornack (1919-1959), a popular Professor of History at Dartmouth until his death of cancer in 1959 Professor McCornack, a pioneer advocate of non-Western studies at the College, influenced Wheeler and at least four other Dartmouth graduates of the 1950's to pursue professional careers in African Studies.

The book surveys both historical and contemporary Angola, Portugal's largest overseas possession. Concentrating in large part on the deeds of the colonizers rather than the colonized, it combines the best in traditional colonial historical scholarship with in-depth reporting of events in Angola's past decade—ten years marked by nationalist rebellion, guerilla war, and an all-out military effort by Portugal to hold on to one of the last bastions of white colonial rule on the African continent.

Part One of Angola, written by Wheeler, focuses on the history of this area up to 1961. Since Portugal has the dubious distinction of being the first and last colonial power in Africa, the relations of Europeans and Africans in Angola span a period of more than four centuries. During the first three, hundred years, the necessities of Portugal's slave trade to Tropical America defined group contact. Since the late nineteenth century, new developments have transformed Angola into a European settlement colony, and have produced a growing plural society fraught with increasing antagonisms. Writing precisely and well, Wheeler skillfully describes the internal dynamics of this long colonial contact—the expansion of Portuguese control over the indigenous population, the effects of the slave trade on an area which supplied so many millions of human beings to earn the name "Black Mother," and the development and consequences of Portuguese racial mythologies when translated into colonial policies.

Part Two, written by Rene Pélissier, dealing with the story since 1961, is less readable than Wheeler's contribution. It suffers somewhat from the lack of historical perspective which greater chronological distance from the events might have supplied. Nonetheless, Pelissier is successful in shedding light on the various groups vying for power and on Portugal's social, economic, and political policies in Angola since the outbreak of rebellion.

Finally, in Park Three, Wheeler evaluates recent events in Angola and concludes that its independence from Portugal is inevitable. Right or not, the status of Angola is crucial to the entire future political course of Southern Africa. And in helping to shed light on this entremely important area of the African continent, this book is timely and important.

Assistant Professor of History at Dartmouth,Mr. Spitzer teaches three courses, History ofAfrica to 1880, History of Africa Since 1880,and Modern Imperialism and Non-WesternNationalism.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

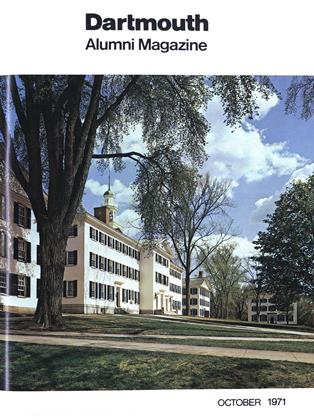

FeatureThayer School's Centennial

October 1971 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28 -

Feature

FeatureOMBUDSMAN

October 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

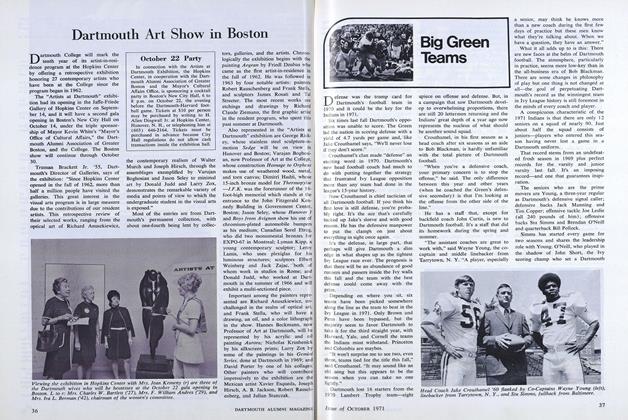

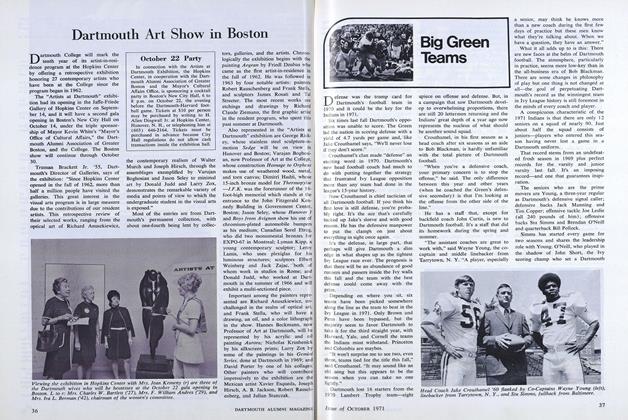

FeatureDartmouth Art Show in Boston

October 1971 -

Feature

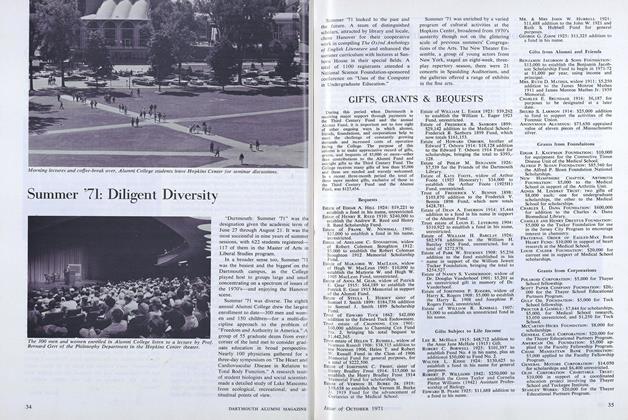

FeatureSummer '71: Diligent Diversity

October 1971 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

October 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1971

LEO SPITZER

Books

-

Books

BooksFraternity, Published Monthly

MAY 1930 -

Books

BooksTHE CONSTITUTION AND THE MEN WHO MADE IT

January 1937 -

Books

BooksTHE DOCTOR OF MAGIC

June 1947 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksTHE LATE GREAT CREATURE.

APRIL 1972 By J. DONALD O'HARA '53 -

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS WHAT MAKES SAMMY RUN

April 1941 By Sidney Cox -

Books

BooksTHE LOGIC OF LANGUAGE

November 1939 By Stearns Morse