The College community is his bailiwick, its members his concern, but he has only one client - and that is justice

"The combined role of a sounding board and a tuning fork."

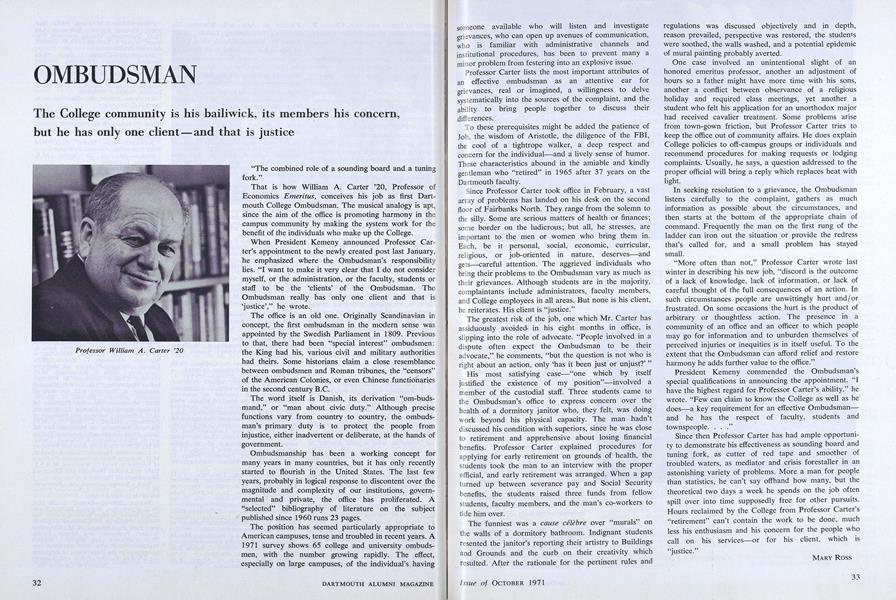

That is how William A. Carter '20, Professor of Economics Emeritus, conceives his job as first Dartmouth College Ombudsman. The musical analogy is apt, since the aim of the office is promoting harmony in the campus community by making the system work for the benefit of the individuals who make up the College.

When President Kemeny announced Professor Carter's appointment to the newly created post last January, he emphasized where the Ombudsman's responsibility lies. "I want to make it very clear that I do not consider myself, or the administration, or the faculty, students or staff to be the 'clients' of the Ombudsman. The Ombudsman really has only one client and that is 'justice'," he wrote.

The office is an old one. Originally Scandinavian in concept, the first ombudsman in the modern sense was appointed by the Swedish Parliament in 1809. Previous to that, there had been "special interest" ombudsmen: the King had his, various civil and military authorities had theirs. Some historians claim a close resemblance between ombudsmen and Roman tribunes, the "censors" of the American Colonies, or even Chinese functionaries in the second century B.C.

The word itself is Danish, its derivation "om-budsmand," or "man about civic duty." Although precise functions vary from country to country, the ombudsman's primary duty is to protect the people from injustice, either inadvertent or deliberate, at the hands of government.

Ombudsmanship has been a working concept for many years in many countries, but it has only recently started to flourish in the United States. The last few years, probably in logical response to discontent over the magnitude and complexity of our institutions, governmental and private, the office has proliferated. A "selected" bibliography of literature on the subject published since 1960 runs 23 pages.

The position has seemed particularly appropriate to American campuses, tense and troubled in recent years. A 1971 survey shows 65 college and university ombudsmen, with the number growing rapidly. The effect, especially on large campuses, of the individual's having someone available who will listen and investigate grievances, who can open up avenues of communication, who is familiar with administrative channels and institutional procedures, has been to prevent many a minor problem from festering into an explosive issue.

professor Carter lists the most important attributes of an effective ombudsman as an attentive ear for grievances, real or imagined, a willingness to delve systematically into the sources of the complaint, and the ability to bring people together to discuss their differences.

To these prerequisites might be added the patience of Job, the wisdom of Aristotle, the diligence of the FBI, the cool of a tightrope walker, a deep respect and concern for the individual—and a lively sense of humor. These characteristics abound in the amiable and kindly gentleman who "retired" in 1965 after 37 years on the Dartmouth faculty.

Since Professor Carter took office in February, a vast array of problems has landed on his desk on the second floor of Fairbanks North. They range from the solemn to the silly. Some are serious matters of health or finances; some border on the ludicrous; but all, he stresses, are important to the men or women who bring them in. Each, be it personal, social, economic, curricular, religious, or job-oriented in nature, deserves—and gets—careful attention. The aggrieved individuals who bring their problems to the Ombudsman vary as much as their grievances. Although students are in the majority, complaintants include administrators, faculty members, and College employees in all areas. But none is his client, he reiterates. His client is "justice."

The greatest risk of the job, one which Mr. Carter has assiduously avoided* in his eight months in office, is slipping into the role of advocate. "People involved in a dispute often expect the Ombudsman to be their advocate," he comments, "but the question is not who is right about an action, only 'has it been just or unjust?' "

His most satisfying case—"one which by itself justified the existence of my position"—involved a member of the custodial staff. Three students came to the Ombudsman's office to express concern over the health of a dormitory janitor who, they felt, was doing work beyond his physical capacity. The man hadn't discussed his condition with superiors, since he was close to retirement and apprehensive about losing financial benefits. Professor Carter explained procedures for applying for early retirement on grounds of health, the students took the man to an interview with the proper official, and early retirement was arranged. When a gap turned up between severance pay and Social Security benefits, the students raised three funds from fellow students, faculty members, and the man's co-workers to tide him over.

The funniest was a cause celebre over "murals" on the walls of a dormitory bathroom. Indignant students resented the janitor's reporting their artistry to Buildings and Grounds and the curb on their creativity which resulted. After the rationale for the pertinent rules and regulations was discussed objectively and in depth, reason prevailed, perspective was restored, the students were soothed, the walls washed, and a potential epidemic of mural painting probably averted.

One case involved an unintentional slight of an honored emeritus professor, another an adjustment of hours so a father might have more time with his sons, another a conflict between observance of a religious holiday and required class meetings, yet another a student who felt his application for an unorthodox major had received cavalier treatment. Some problems arise from town-gown friction, but Professor Carter tries to keep the office out of community affairs. He does explain College policies to off-campus groups or individuals and recommend procedures for making requests or lodging complaints. Usually, he says, a question addressed to the proper official will bring a reply which replaces heat with light.

In seeking resolution to a grievance, the Ombudsman listens carefully to the complaint, gathers as much information as possible about the circumstances, and then starts at the bottom of the appropriate chain of command. Frequently the man on the first rung of the ladder can iron out the situation or provide the redress that's called for, and a small problem has stayed small.

"More often than not," Professor Carter wrote last winter in describing his new job, "discord is the outcome of a lack of knowledge, lack of information, or lack of careful thought of the full consequences of an action. In such circumstances people are unwittingly hurt and/or frustrated. On some occasions the hurt is the product of arbitrary or thoughtless action. The presence in a community of an office and an officer to which people may go for information and to unburden themselves of perceived injuries or inequities is in itself useful. To the extent that the Ombudsman can afford relief and restore harmony he adds further value to the office."

President Kemeny commended the Ombudsman's special qualifications in announcing the appointment. "I have the highest regard for Professor Carter's ability," he wrote. "Few can claim to know the College as well as he does—a key requirement for an effective Ombudsman—and he has the respect of faculty, students and townspeople...."

Since then Professor Carter has had ample opportunity to demonstrate his effectiveness as sounding board and tuning fork, as cutter of red tape and smoother of troubled waters, as mediator and crisis forestaller in an astonishing variety of problems. More a man for people than statistics, he can't say offhand how many, but the theoretical two days a week he spends on the job often spill over into time supposedly free for other pursuits. Hours reclaimed by the College from Professor Carter s "retirement" can't contain the work to be done, much less his enthusiasm and his concern for the people who call on his services—or for his client, which is "justice."

Professor William A. Carter '20

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThayer School's Centennial

October 1971 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28 -

Feature

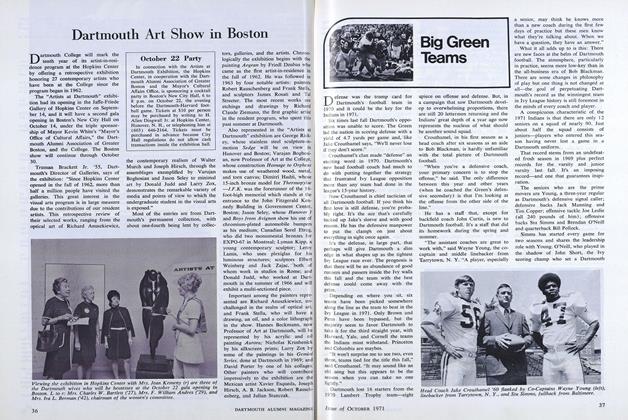

FeatureDartmouth Art Show in Boston

October 1971 -

Feature

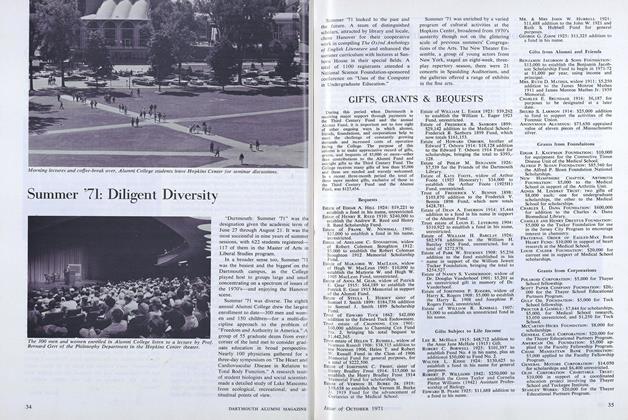

FeatureSummer '71: Diligent Diversity

October 1971 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

October 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1971 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

October 1971 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER

MARY ROSS

-

Article

ArticleTriple-Threat Academician

DECEMBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureAnti-Bigot

JANUARY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

OCTOBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticlePrairie Ornithologist

NOVEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleLost and Found: Sino-American Reunion

JUNE 1982 By Mary Ross

Features

-

Feature

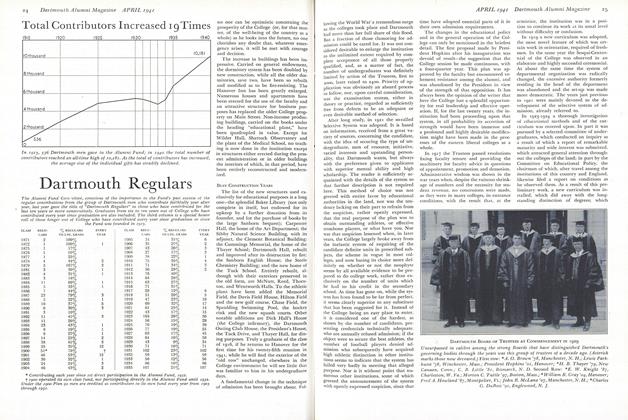

FeatureDartmouth Regulars

April 1941 -

Feature

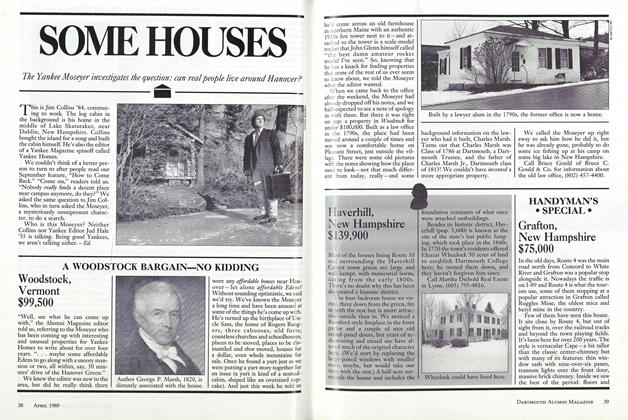

FeatureHANDYMAN'S SPECIAL

APRIL 1989 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWrong Scare

MARCH 1995 By David M. Shribman '76 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1963

JULY 1963 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureThe Most Dangerous Gap of All

NOVEMBER 1969 By THOMAS J. McINTYRE '37 -

Feature

FeatureIf you spent the winter in Buffalo, Imagine This

April 1977 By THOMAS SHERRY