TO THE EDITOR:

Professor Jonathan Mirsky's review of my book Vietnam Crisis: A DocumentaryHistory in the July issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE appears to me to require a response. This request for "equal time" appears warranted for two reasons. The first has to do with the nature of a book review, the second with conceptions of history.

In essence, Professor Mirsky appears to have lost sight of what a book review is all about. As I understand the phenomenon, the idea is to provide some guidance to readers about the content of a work, its possible value, and whether or not they should buy it, read it, or ignore it altogether. Professor Mirsky's review does not do this. The reader of the review would not, I fear, obtain a very clear idea of what the book is about nor much idea of its value. He would find out that Professor Mirsky has certain political views and that my book—whatever its other merits or deficiencies—does not completely accord with his own political philosophy.

Rather than reviewing the book, Professor Mirsky has used the opportunity to grind his own axes about Vietnam in light of the initial sensational disclosures of the "Pentagon Papers" by The New York Times. These, he appears to feel, are the nearest thing to revealed truth available, a surprisingly naive attitude for an historian, and they dominate his thinking to the exclusion of all else. Now, while I have no particular objection to Professor Mirsky expressing his own views, I do object to his utilization of a book review to do it. He has had, and continues to have, ample opportunity to make his position known in other places. He does not need to turn a book review into a private, largely irrelevant, and sometimes incoherent polemic....

I might also observe that Professor Mirsky appears to have missed the point of the work as a whole, for it is principally a source book, not a definitive narrative history, and all the appropriate disclaimers are contained in the Preface. It does not claim to be complete—quite to the contrary—and the principal functions of an index are served by the extensive Table of Contents.

Professor Mirsky has also missed the point of the Bibliography which—as I clearly stated—is (1) selected; (2) consists only of secondary works, almost all books; and (3) is limited to the period treated in the collection (1940-1956). A complete bibliography on Viet-Nam would be a book in its own right (there are several already) as Professor Mirsky well knows. I consider memoirs (such as works by Eden, Acheson, Eisenhower, Laniel, Navarre, and Sabattier) to be primary sources, not secondary analyses, along with primarily ideological works by Vietnamese such as Vo Nguyen Giap, Pham Van Dong, Ho Chi Minh, Ngo Dinh Diem, and others both North and South. The work by Kahin and Lewis deals primarily with matters after 1956, and will be cited in the appropriate volume of the collection. How Professor Mirsky reaches the conclusion that Gabriel Kolko has written something which should be included in this particular bibliography escapes me.

My second reason for this response is more basic and deals with matters of history, historians, and historiography. As I read his review here and his works in other places, Professor Mirsky belongs to the school of "history as weapon," frequently identified (wrongly) as "revisionism." For Mirsky, history is not a source of enlightenment nor an attempt to present some approximation of objective truth but, rather, a grab bag from which the true believer may select those items (and only those items) which ex postfacto justify his position. Because Professor Mirsky operates on the basis of certain assumptions which dominate his thinking, he looks at history (and anything else) only to the extent that it supports those assumptions. Thus a work either supports his point of view, or must be twisted to support that view (there are a couple of classic examples of that in the review), or must be either condemned or ignored.

Now there is nothing particularly wrong with one who chooses to employ those particular techniques, in the proper place and provided that the reader is told what is going on. Such staunch advocacy of perceived right or condemnation of perceived wrong is a common, understandable human phenomenon and is a basic stimulus to intellectual and moral progress. But it is polemic, not history.

The problem in this instance is that Professor Mirsky has tried to evaluate an historical effort in polemical terms. My own effort was to present something as "unloaded" as possible given the resources available. Having done that, and with considerable effort, it is disconcerting to run into a review, such as Professor Mirsky's, whose major point appears to be that I don't make a valiant effort to demonstrate against all obstacles (real or imagined) how nasty has been American policy in Vietnam since some arbitrary point in time.

Again, Professor Mirsky is free to believe and to write as he judges best. I simply object to his attempt to attribute his views to my book or to analyze that work only on the basis of whether or not it suits his political fancy.

" As one who received his primary training in history at Dartmouth, I hoped for a review in the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine which would examine my work for its possible historical value and contribution, not for its political rectitude as defined by one individual. I certainly did not expect a review which is little more than a spring- board for acerbic polemic. I expected a job from somebody who felt enough concern to read the work and to discuss it without polemicizing at every opportunity. Come to think of it, I would feel better had the review been a well-done polemic.

Medjord, Mass.Mr. Cameron is Assistant Dean of TheFletcher School of Law and Diplomacy atTufts University.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThayer School's Centennial

October 1971 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28 -

Feature

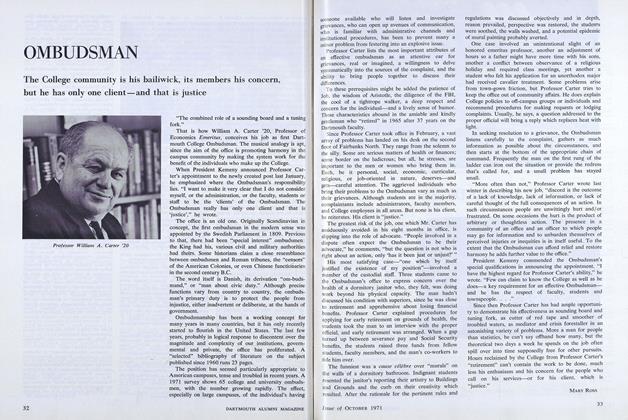

FeatureOMBUDSMAN

October 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

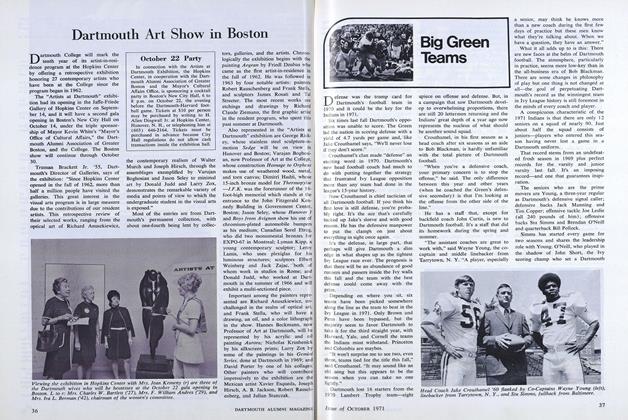

FeatureDartmouth Art Show in Boston

October 1971 -

Feature

FeatureSummer '71: Diligent Diversity

October 1971 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

October 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

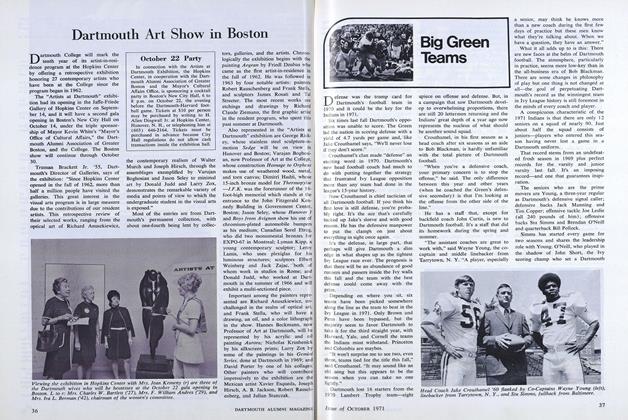

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1971

Article

-

Article

ArticleBILLY SUNDAY

February 1917 -

Article

ArticleStudent Dies from Injuries Received in Dorm Scuffle

May 1949 -

Article

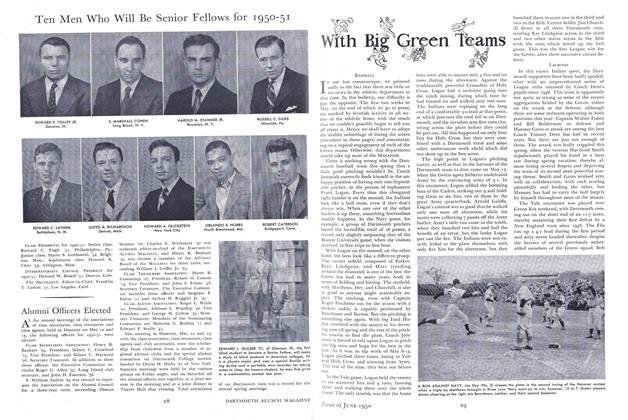

ArticleTen Men Who Will Be Senior Fellows for 1950-51

June 1950 -

Article

Article$100,000 a Day, Not Counting Sundays

September 1978 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

Winter 1993 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22