"It's a matter of quality."

"People are tired of mass-produced junk that isn't suited to their needs. What good is affluence if your money won't buy things that will last?"

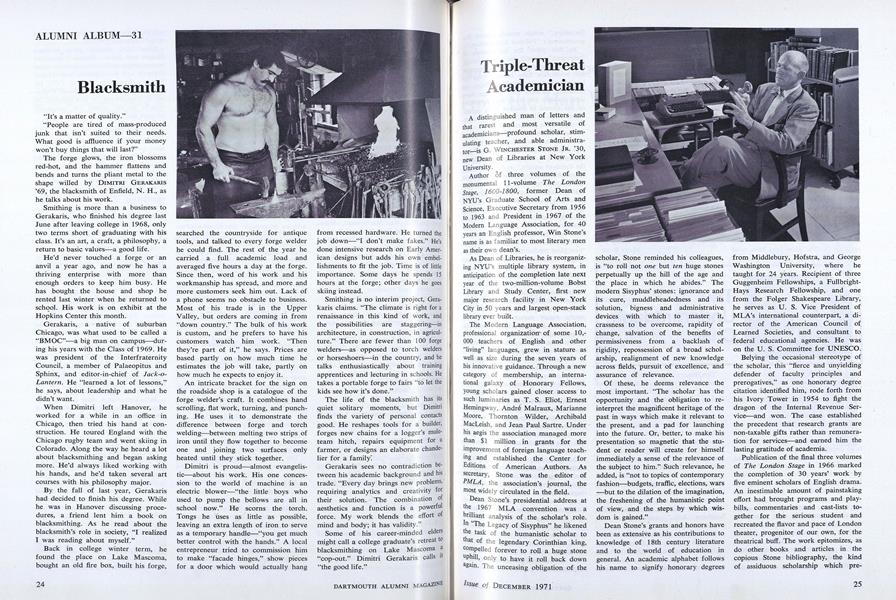

The forge glows, the iron blossoms red-hot, and the hammer flattens and bends and turns the pliant metal to the shape willed by DIMITRI GERAKARIS '69, the blacksmith of Enfield, N. H., as he talks about his work.

Smithing is more than a business to Gerakaris, who finished his degree last June after leaving college in 1968, only two terms short of graduating with his class. It's an art, a craft, a philosophy, a return to basic values—a good life.

He'd never touched a forge or an anvil a year ago, and now he has a thriving enterprise with more than enough orders to keep him busy. He has bought the house and shop he rented last winter when he returned to school. His work is on exhibit at the Hopkins Center this month.

Gerakaris, a native of suburban Chicago, was what used to be called a "BMOC"—a big man on campus—during his years with the Class of 1969. He was president of the Interfraternity Council, a member of Palaeopitus and Sphinx, and editor-in-chief of Jack-o-Lantern. He "learned a lot of lessons," he says, about leadership and what he didn't want.

When Dimitri left Hanover, he worked for a while in an office in Chicago, then tried his hand at construction. He toured England with the Chicago rugby team and went skiing in Colorado. Along the way he heard a lot about blacksmithing and began asking more. He'd always liked working with his hands, and he'd taken several art courses with his philosophy major.

By the fall of last year, Gerakaris had decided to finish his degree. While he was in Hanover discussing procedures, a friend lent him a book on blacksmithing. As he read about the blacksmith's role in society, "I realized I was reading about myself."

Back in college winter term, he found the place on Lake Mascoma, bought an old fire box, built his forge, searched the countryside for antique tools, and talked to every forge welder he could find. The rest of the year he carried a full academic load and averaged five hours a day at the forge. Since then, word of his work and his workmanship has spread, and more and more customers seek him out. Lack of a phone seems no obstacle to business. Most of his trade is in the Upper Valley, but orders are coming in from "down country." The bulk of his work is custom, and he prefers to have his customers watch him work. "Then they're part of it," he says. Prices are based partly on how much time he estimates the job will take, partly on how much he expects to enjoy it.

An intricate bracket for the sign on the roadside shop is a catalogue of the forge welder's craft. It combines hand scrolling, flat work, turning, and punching. He uses it to demonstrate the difference between forge and torch welding—between melting two strips of iron until they flow together to become one and joining two surfaces only heated until they stick together.

Dimitri is proud—almost evangelistic—about his work. His one concession to the world of machine is an electric blower—"the little boys who used to pump the bellows are all in school now." He scorns the torch. Tongs he uses as little as possible, leaving an extra length of iron to serve as a temporary handle—"you get much better control with the hands." A local entrepreneur tried to commission him to make "facade hinges," show pieces for a door which would actually hang from recessed hardware. He turned the job down—"I don't make fakes." He's done intensive research on Early American designs but adds his own embellishments to fit the job. Time is of little importance. Some days he spends 15 hours at the forge; other days he goes skiing instead.

Smithing is no interim project, Gerakaris claims. "The climate is right for a renaissance in this kind of work, and the possibilities are staggering—in architecture, in construction, in agriculture." There are fewer than 100 forge welders—as opposed to torch welders or horseshoers—in the country, and he talks enthusiastically about training apprentices and lecturing in schools. He takes a portable forge to fairs "to let the kids see how it's done."

The life of the blacksmith has its quiet solitary moments, but Dimitri finds the variety of personal contacts good. He reshapes tools for a builder, forges new chains for a logger's muleteam hitch, repairs equipment for a farmer, or designs an elaborate chandelier for a family.

Gerakaris sees no contradiction between his academic background and his trade. "Every day brings new problems, requiring analytics and creativity for their solution. The combination of aesthetics and function is a powerful force. My work blends the effort of mind and body; it has validity."

Some of his career-minded elders might call a college graduate's retreat to blacksmithing on Lake Mascoma a "cop-out." Dimitri Gerakaris calls it "the good life."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

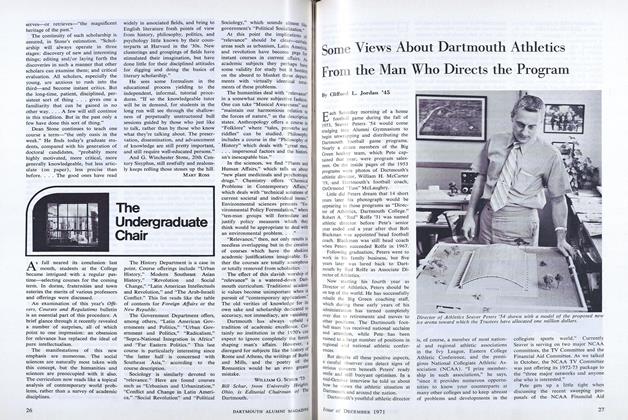

FeatureSome Views About Dartmouth Athletics From the Man Who Directs the Program

December 1971 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Feature

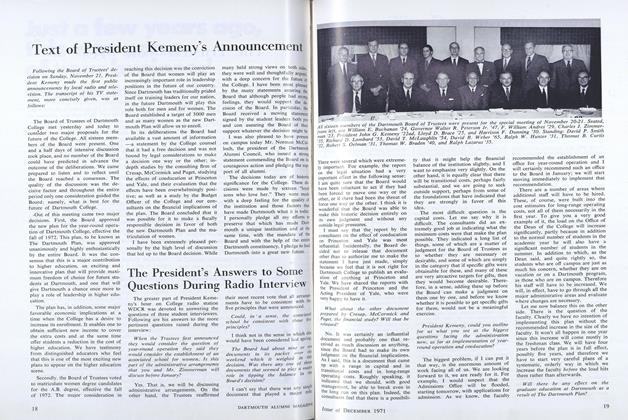

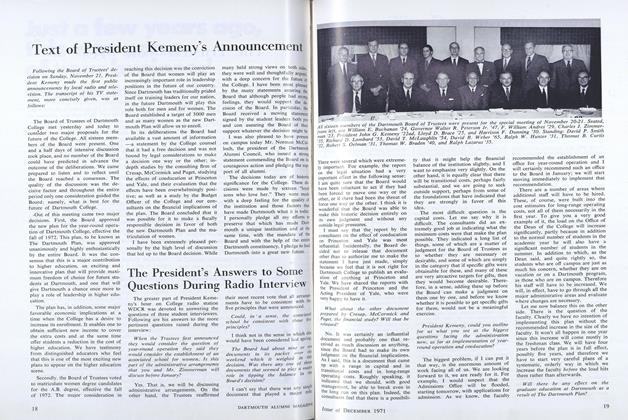

FeatureThe President's Answers to Some Questions During Radio Interview

December 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Final Report

December 1971 -

Feature

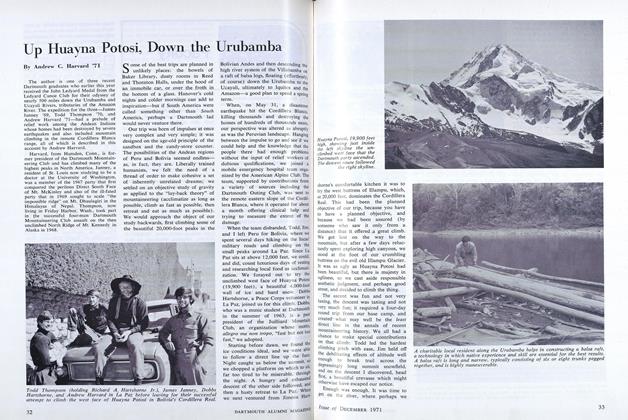

FeatureUp Huayna Potosi, Down the Urubamba

December 1971 By Andrew C. Harvard '71 -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees Vote "Yes"

December 1971 -

Feature

FeatureText of President Kemeny's Announcement

December 1971