The author is one of three recent Dartmouth graduates who earlier this year received the John Ledyard Medal from the Ledyard Canoe Club for their odyssey of nearly 500 miles down the Urubamba and Ucayali Rivers, tributaries of the Amazon River. The expedition for the three—James Janney '69, Todd Thompson '70, and Andrew Harvard '71—had a prelude of relief work among the Andean Indians whose homes had been destroyed by severe earthquakes and also included mountain climbing in the remote Cordillera Blanca range, all of which is described in this account by Andrew Harvard.

Harvard, from Hamden, Conn., is former president of the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club and has climbed many of the highest peaks in North America. Janney, a resident of St. Louis now studying to be a doctor at the University of Washington, was a member of the 1967 party that first conquered the perilous Direct South Face of Mt. McKinley and also of the ill-fated party that in 1969 sought to scale "the impossible ridge" on Mt. Dhaulagiri in the Himalayas of Nepal. Thompson, now living in Friday Harbor, Wash., took part in the successful four-man Dartmouth Mountaineering Club assault on the then unclimbed North Ridge of Mt. Kennedy in Alaska in 1968.

Some of the best trips are planned in unlikely places: the bowels of Baker Library, dusty rooms in Reed and Thornton Halls, under the hood of an immobile car, or over the froth in the bottom of a glass. Hanover's cold nights and colder mornings can add to inspiration—but if South America were called something other than South America, perhaps a Dartmouth lad would never venture there.

Our trip was born of impulses at once very complex and very simple; it was designed on the age-old principle of the sandbox and the candy-store counter. The possibilities of the Andean regions of Peru and Bolivia seemed endlessas, in fact, they are. Liberally trained humanists, we felt the need of a thread of order to make cohesive a set of inherently unrelated dreams; we settled on an objective study of gravity as applied to the "lay-back theory" of mountaineering (acclimatize as long as possible, climb as fast as possible, then retreat and eat as much as possible). We would approach the object of our study backwards, first climbing some of the beautiful 20,000-foot peaks in the Bolivian Andes and then descending the high river system of the Villabamba on a raft of balsa logs, floating (effortlessly, of course) down the Urubamba to the Ucayali, ultimately to Iquitos and the Amazon—a good plan to speed a spring term.

When, on May 31, a disastrous earthquake hit the Cordillera Blanca. killing thousands and destroying the homes of hundreds of thousands more, our perspective was altered as abruptly as was the Peruvian landscape. Hanging between the impulse to go and see if we could help and the knowledge that the people there had enough problems without the input of relief workers of dubious qualifications, we joined a mobile emergency hospital team orga- nized by the American Alpine Club. The team, supported by contributions from a variety of sources including the Dartmouth Outing Club, was sent to the remote eastern slope of the Cordillera Blanca, where it operated for about a month offering clinical help and trying to measure the extent of the damage.

When the team disbanded, Todd, Jim, and I left Peru for Bolivia, where we spent several days hiking on the Incas' military roads and climbing on the small peaks around La Paz. Since La Paz sits at above 12,000 feet, we could, and did, count luxurious days of resting and researching local food as acclimatization. We forayed out to try the unclimbed west face of Huayna Potosi (19,900 feet), a beautiful 4,000-foot wall of ice and hard snow. Dobbs Hartshorne, a Peace Corps volunteer in La Paz, joined us for this climb. Dobbs, who was a music student at Dartmouth in the summer of 1963, is a past president of the Juilliard Mountain Club, an organization whose motto, allegro ma non tropo, "fast but not too fast," we adopted.

Starting before dawn, we found the ice conditions ideal, and we were able to follow a direct line up the face. Night caught us below the summit, so we chopped a platform on which to sit, far too tired to be miserable, through the night. A hungry and exhausted descent of the other side followed, an then a hasty retreat to La Paz. When we next ventured from Jimena Hart shorne's comfortable kitchen it was to try the west buttress of Illampu, which, at 20,000 feet, dominates the Cordillera Real. This had been the planned objective of our trip, because you have to have a planned objective, and because we had been assured (by someone who saw it only from a distance) that it offered a great climb. We got lost on the way to the mountain, but after a few days reluctantly spent exploring high canyons, we stood at the foot of our crumbling buttress on the evil old Illampu Glacier. It was as ugly as Huayna Potosi had been beautiful, but there is majesty in ugliness, so we cast aside responsible aesthetic judgment, and perhaps good sense, and decided to climb the thing.

The ascent was fun and not very taxing, the descent was taxing and not very much fun; it required a four-day round trip from our base camp, and created what may well be the least direct line in the annals of recent mountaineering history. We all had a chance to make special contributions °n that climb: Todd led the hardest climbing pitch with ease, Jim held off the debilitating effects of altitude well enough to break trail across the depressingly long summit snowfield, and on the descent I discovered, head fst, a beautiful crevasse which might nerwise have escaped our notice.

Enough was enough. It was time to get on the river, where perhaps we from the Atlantic, halfway across the continent. From Iquitos, Todd continued down the Amazon toward the coast, while Jim and I flew back to avoid the late-fees at our respective registrars' offices.

At the confluence of the Urubamba and Apurimac Rivers, we jumped down the Ucayali on a Peruvian Air Force DC-3 to Pucallpa, an important inland trading town. There we boarded a barge carrying beer, soap, and bananas to Iquitos, some 800 river miles away. Iquitos is a deep-water port, Peru's "western seacoast," serving cargo ships belonged in the first place. We went by bus, train, and truck to the Urubamba, where we could construct a raft of balsa logs, thanks to the generosity, hospitality, and compassion of the river farmers. A balsa raft is long and narrow, typically consisting of six or eight trunks pegged together with the outside trunks slightly higher than the center, or keel, trunks; it is a comfortable and highly maneuverable craft. For about two weeks we followed the current, feeling, briefly, the magic of all the rivers and the profound dignity and subtle beauty of this one. The Urubamba starts high in the Villabamba, the mountain jungle which swallowed up the remnants of the retreating Inca Empire, and runs to the flat Amazon basin; it showed us many faces, but was magnanimous. The river and its people are a living, growing organism, and as we passed through we were accepted as pilgrims from a distant, perhaps less fortunate, culture.

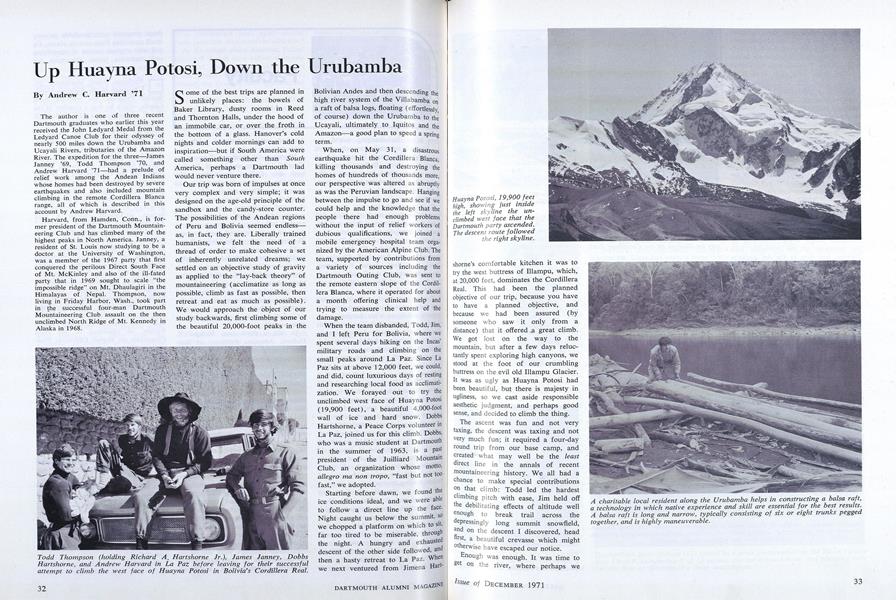

Todd Thompson (holding Richard A, Hartshorne Jr.), James Janney, DobbsHartshorne, and Andrew Harvard in La Paz before leaving for their successfulattempt to climb the west face of Huayna Potosi in Bolivia's Cordillera Real.

A charitable local resident along the Urubamba helps in constructing a balsa raft,a technology in which native experience and skill are essential for the best results.A balsa raft is long and narrow, typically consisting of six or eight trunks peggedtogether, and is highly maneuverable.

Todd Thompson in an ice-choked chimney on Illampu in the Cordillera Real.

Sunday morning market in Pisac, once a fortress town under the Inca Empire.Women in the foreground, wearing their famous hats, discuss the price of potatoes,the staple of Peru's highlands and the region's major product.

The author attempting minor surgery ona raft paddle along the Urubamba.

Janney at the Pisac Temple, one of themost exquisite ruin sites remaining fromthe ancient Inca Empire.

Thompson repacking the party's raft,a daily task since balsa rafts must be unloaded and beached to dry overnight.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

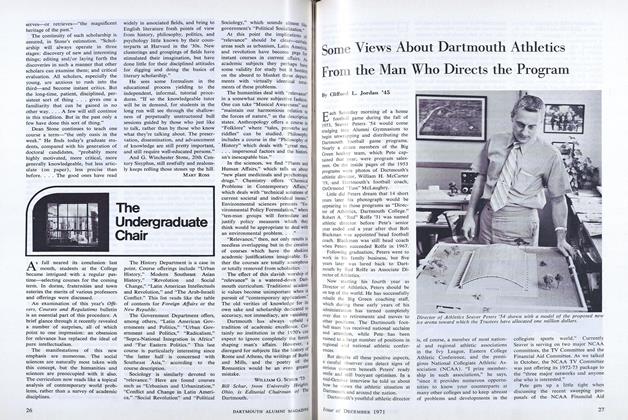

FeatureSome Views About Dartmouth Athletics From the Man Who Directs the Program

December 1971 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe President's Answers to Some Questions During Radio Interview

December 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Final Report

December 1971 -

Feature

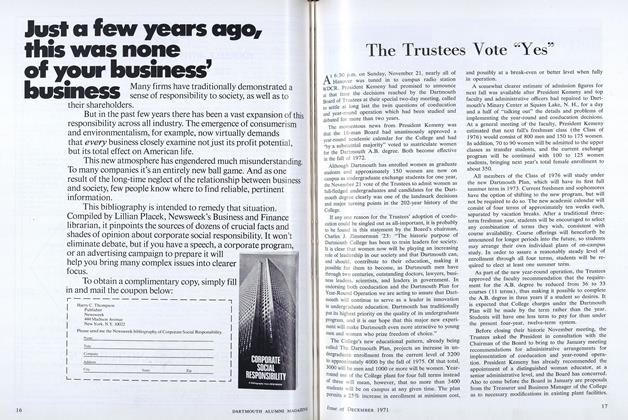

FeatureThe Trustees Vote "Yes"

December 1971 -

Feature

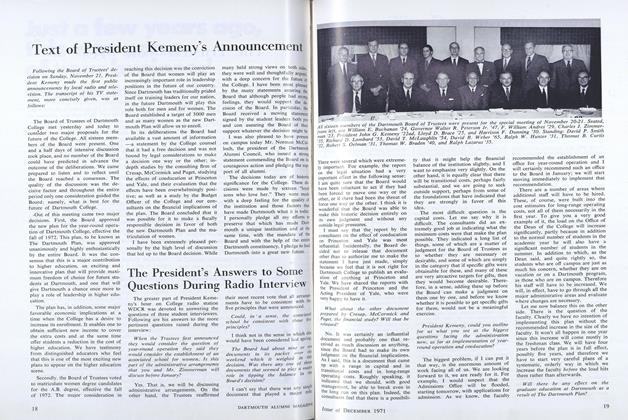

FeatureText of President Kemeny's Announcement

December 1971 -

Article

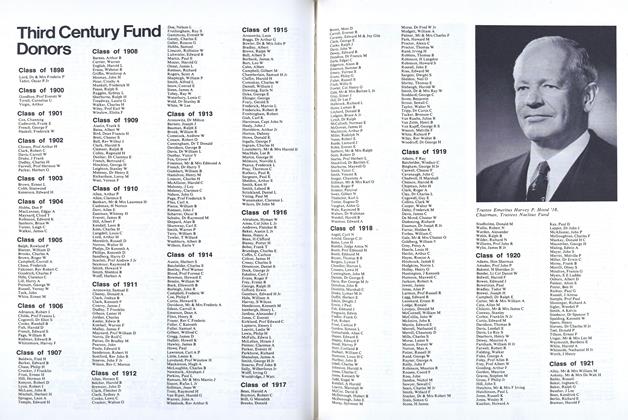

ArticleThird Century Fund Donors

December 1971

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryExcerpts from Beverly Sills' Commencement Address

June • 1985 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHALDEN CALCULEX CIRCULAR SLIDE RULE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seduction of a Corporate Recruit

Sept/Oct 2003 By JONATHAN E. ZIMMERMAN ’98 -

Feature

FeatureOliver Wendell Holmes Slept – and Taught – Here

May 1956 By ROBERT S. BLUM '55 -

Feature

FeatureThe Humanistic Pursuit of Values

MAY 1967 By ROBIN J. SCROGGS -

Feature

FeatureScience and Technology Under Siege

SEPT. 1977 By Thomas Laaspere