As fall neared its conclusion last month, students at the College became intrigued with a regular pastime—selecting courses for the coming term. In dorms, fraternities and town eateries the merits of various professors and offerings were discussed.

An examination of this year's Officers, Courses and Regulations bulletin is an essential part of this procedure. A brief glance through it recently revealed a number of surprises, all of which point to one impression: an obsession for relevance has replaced the ideal of pure intellectualism.

The manifestations of this new emphasis are numerous. The social sciences are naturally most taken with this concept, but the humanities and sciences are preoccupied with it also. The curriculum now reads like a topical analysis of contemporary world problems, rather than a survey of academic disciplines.

The History Department is a case in point. Course offerings include "Urban History," Modern Southeast Asian History," "Revolution and Social Change," "Latin American Intellectuals and Revolution," and "The Arab-Israeli Conflict." This list reads like the table of contents for Foreign Affairs or the New Republic.

The Government Department offers, among others, "Latin American Governments and Politics," "Urban Government and Politics," "Radicalism," "Supra-National Integration in Africa" and "Far Eastern Politics." This last course is particularly interesting since "the latter half is concerned with Southeast Asia," according to the course description.

Sociology is similarly devoted to "relevance." Here are found courses such as "Urbanism and Urbanization," "Conflict and Change in Latin America," "Social Revolution" and "Political Sociology," which sounds almost like government's "Political Socialization,"

At this point the implications of "relevance" should be clear—certain areas such as urbanism, Latin America and revolution have become pegs for instant courses in current affairs. As academic subjects they perhaps have some validity for study but it borders on the absurd to blanket three departments with virtually identical treatments of these problems.

The humanities deal with "relevance" in a somewhat more subjective fashion One can take "Musical Awareness" and "maintain our harmonious relation to the forces of nature," as the description states. Anthropology offers a course in "Folklore" where "tales, proverbs and riddles" can be studied. Philosophy includes a course in the "Philosophy of History" which deals with "great men, . . . impersonal factors and the historian's inescapable bias."

In the sciences, we find "Plants and Human Affairs," which tells us about "new plant medicinals and psychotropic drugs." Chemistry offers "Chemical Problems in Contemporary Affairs," which deals with "technical solutions of current societal and individual issues." Environmental sciences presents "Environmental Policy Formulation," where "ten-man groups will formulate and justify policy measures which they think would be appropriate to deal with an environmental problem. . ."

"Relevance," then, not only results in needless overlapping but in the creation of courses which have the shakiest academic justifications imaginable. Either the courses are totally amorphous or totally removed from scholastics.

The effect of this slavish worship of "relevance" is a watered-down Dartmouth curriculum. Traditional academic values become unimportant when in pursuit of "contemporary applications. The old verities of knowledge for its own sake and scholarship dedicated to accuracy, not immediacy, are vanishing.

Dartmouth has always upheld a tradition of academic excellence. Certainly no institution in the 1970's can expect to ignore completely the forces shaping man's affairs. However, a disregard for subjects like the history of Rome and Athens, the writings of Burke and Mills, and the poetry of the Romantics would be an even greater mistake.

Bill Schur, from University HeightS,Ohio, is Editorial Chairman of The Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

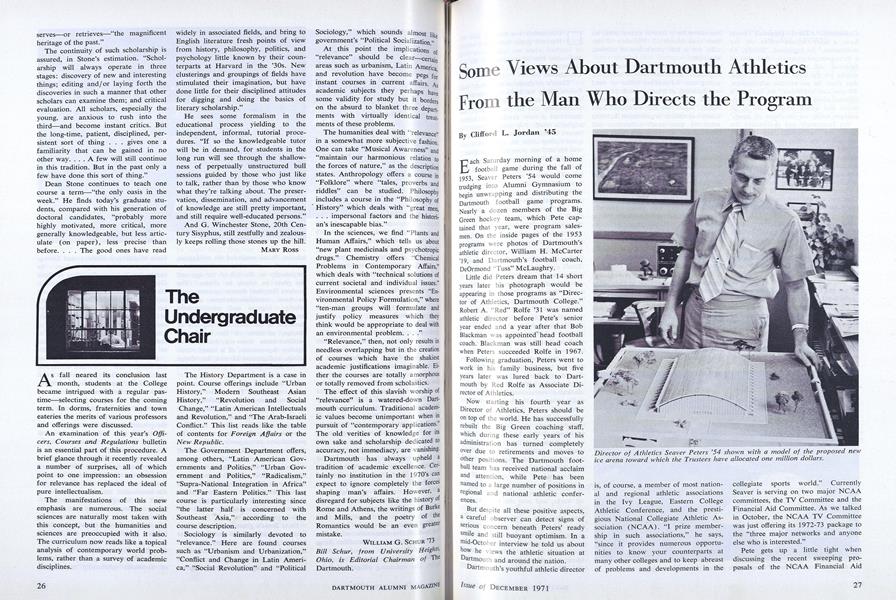

FeatureSome Views About Dartmouth Athletics From the Man Who Directs the Program

December 1971 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe President's Answers to Some Questions During Radio Interview

December 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Final Report

December 1971 -

Feature

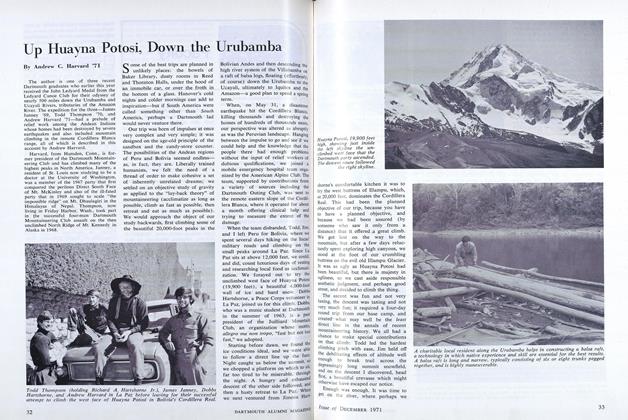

FeatureUp Huayna Potosi, Down the Urubamba

December 1971 By Andrew C. Harvard '71 -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees Vote "Yes"

December 1971 -

Feature

FeatureText of President Kemeny's Announcement

December 1971