During the recent period when defamation of the United States seemed to have peaked at the United Nations head quarters an enterprising book publisher might have sold out an entire edition in a single day. With a new book entitled Disaster at Bari on display, the publisher might have opened a sales booth canopied by a banner saying "Poison gas made in the United States killed hundreds during World War II." And those words would have been correct.

Written by Glenn B. infield, an author skilled in the presentation of verified fact, the book is about the results of a Nazi air attack on the Italian harbor of Bari in the middle of the war. At the time of the raid, the port was choked with a variety of warships and transport vessels whose skippers had been assured that attack was impossible. But, the shipping toll was so heavy it altered, or delayed, the course of the war to a large extent. But that is not what we are interested in here. For, for pure interest, second only to the disaster itself, is what was revealed by the acuity and resolution of an American medical officer. He was Dr. Stewart F. Alexander M'35.

The present revelation of the presence of American-made mustard gas at Bari during the Luftwaffe attack on December 2, 1943, can be attributed quite wholly to the deduction, against odds, made by Dr. Alexander. This development, as implied, is laced with paradoxes, though the author of Disasterat Bari resolves them through painstaking use of detail. One of the vessels berthed at Bari was the American Liberty ship John Harvey. Some of its crew members knew, or suspected, that part of its cargo was classified, mysterious material. British military personnel manning the port knew the John Harvey was carrying the mustard gas from the United States but were not allowed to reveal it—even if that delation could have cut down the casualties. (This question of maintaining secrecy went to the very top in London, to no avail: the whole matter would still be secret, as far as the British were concerned.)

The immediate effects of the aerial bombing were dramatically evident, of course. Deaths and the injuries from fire and smoke mounted. However, as hours passed, it became evident that the survivors' symptoms did not follow usual courses. As Dr. Alexander enters the picture it becomes a classic case of "the right man at the right place at the right time".—provided that you want to learn the truth, rather than bury it.

True, there were enemy threats of using poison gas. True, with the massive assault on Fortress Europe mounting, this was a critical stage of the war (remembered by the crises at Anzio and on the Radipo). And, true also was the fact that the Allies had decided to be able to retaliate with poison gas. Other less dramatic, though of sequential importance, truths are involved: Stewart Francis Alexander, a young medical officer, had received training in chemical warfare prior to being sent overseas. And when he went abroad, it was to the Mediterranean Theatre.

Crisis is a mild word for the situation at Bari when Hitler's bombers attacked and Lieutenant Colonel Alexander was brought from Algiers to the southern Italian port to help account for the lingering deaths and unhealing burns. Bari had been intended as a major entry into the European battlefield; General Jimmy Doolittle was there, frustrated, trying to establish another Air Force in Italy. At this point the detail-filled book follows Dr. Alexander's adventures, and it is intriguing indeed.

In addition to the aforementioned Doolittle, both Eisenhower and Churchill chill are brought into drama surrounding Dr. Alexander's findings. The disposition of poison gas anywhere was necessarily a matter of high-level policy, and heads of state were concerned. However, Dr. Alexander pursued his investigation as a scientist and, suppressed as they have been until now, his findings are incontrovertible. For a time there seemed to be the possibility that the mustard gas was spread around Bari harbor by the attacking German aircraft, but this was soon disproved. (There is a whole chapter entitled "Colonel, where did the mustard come from?" and it is interesting to note that the following chapter has the title "They die so suddenly, Doctor!")

Author Infield, intent on writing history, never refers to Dr. Alexander as a modern medical military Sherlock Holmes, but the analogy may form in the reader's mind. Dr. Alexander's knowledge, perseverance, skill and self confidence, backgrounded by flame, smoke, sinking ships, the dying and bomb bursts, have to prevail against stone-faced statements that no mustard gas is present. They prevail.

The importance of Dr. Alexander's certainty is reflected by the author when he states that "Bari was the only major poison gas incident of World War II, and it could have had severe repercussions in world propaganda and have led to all-out chemical warfare by both the Allies and Axis. This tragedy was a grim reminder that all nations have secret stores of chemical agents ready for use against each other if the need, in the minds of their leaders, arises. The victims of Bari, both those who died and those who survived, learned the horrors of chemical warfare. Even in an age when the nuclear bomb is the ultimate in weapons, poison gas is still feared just as much. It is hoped that never again will any man, woman or child suffer the torments of another incident such as the Bari disaster."

There are two happy notes of epilogue: National leaders did become aware of tragedies like Bari, and chemical warfare potentials are waning.

Second note: Dr. Alexander, a member of the Dartmouth Medical School Alumni Council, is pacifically practicing medicine in New Jersey.

Dr. Stewart F. Alexander '35M

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Plan

January 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Giving Adds $13.9 Million in Year

January 1972 -

Feature

FeatureConserver of the Crafts

January 1972 -

Feature

FeatureAnti-Bigot

January 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

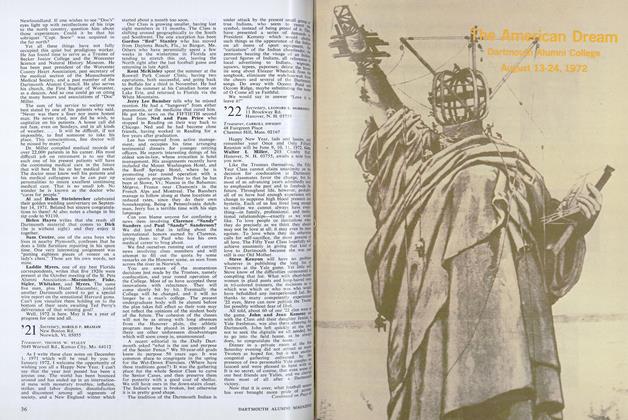

FeatureThe American Dream

January 1972 By A.T.G. -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1972 By RICHARD M. ZUCKERMAN '72

BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38

-

Article

ArticleMedical School

DECEMBER 1971 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

JANUARY 1972 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

FEBRUARY 1972 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

MAY 1972 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Books

BooksDARTMOUTH MEDICAL SCHOOL: THE FIRST 175 YEARS.

APRIL 1973 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Feature

FeatureMedical Care via Television

APRIL 1973 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT, NINETEEN HUNDRED TWELVE

June, 1912 -

Article

ArticleFROM THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

January, 1925 -

Article

ArticleCHENEY '20 .RECEIVES COFFIN FELLOWSHIP A SECOND TIME

August, 1925 -

Article

ArticleNo Opportunities?

March 1940 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

MARCH 1990 -

Article

ArticleTHE PANAMA CANAL; WHAT IT IS; WHAT IT MEANS

June, 1914 By John Barrett, RORERT FLETCHER