First interstate two-way medical television network in the country linksDartmouth-Hitchcock with three other New Hampshire and Vermont centers

The young patient is alert and intelligent-looking. As she sits upright on an examining table, her pleasant face reflects concern, hope and cooperation. The physician uses a tone that is both gentle and businesslike in a period of question- ing that lasts between five and ten minutes. The questions range from current use of medications to general family history, then the physician examines the patient slowly and carefully. At the end, the physician gives specific advice about the patient's aiment, prescribes medicine, and tells the patient when to return for a follow-up examination.

Routine? Standard session in any dotor's office? No. Not on a number of counts, two of them major, one surpassing.

First, the latter. The patient and physician were not even in the same room. They were "in contact" by television. Second, the medical problem involved was dermatological, requiring acute visual examination.

The patient was a 17-year-old girl whose family lives on a farm near Claremont. She developed a rash that, medically, was only temporarily blemishing yet to the youngster was disastrously disfiguring. (Medically, too, of course, the cause of the rash had to be determined.) The girl had heard about the free dermatology clinic at Claremont General Hospital that was part of an experimental medical program involving closed-circuit, two-way television, and asked for an appointment.

The physician who saw her, by TV, was Dr. Marie-Louise Johnson, a prominent dermatologist who joined the faculty of the Dartmouth Medical School two years ago. Shortly after her arrival in Hanover she became part of a now-important move to further the medical use of television.

Two-way, or "interactive," television between the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Complex in Hanover and Claremont General Hospital had had some limited use before the dermatology clinic was established at the latter. But the system took on a new dimension when Dr. Johnson's use of it proved to be successful. Initially, Dr. Johnson, with the help of physician's assistant Thomas C. Hokanson, and her patients "met" and conversed by television but the only separation was their being in different rooms in the basement of Claremont General. After the der- matologist had conducted her interview, made her examination, diagnosed and prescribed, she then met her patient faceto-face to carefully evaluate her television impressions. She found that actually examining the patient neither altered nor enhanced her television diagnosis. Thus, the need for the actual physician-patient meeting was obviated. Instead of going to Claremont to conduct the Clinic, she began doing just that from Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital in Hanover.

Not all medical consultation can be done by television, of course. But, as evidenced by dermatology, there are unexplored areas. In a close-up color television view, the patient's skin trouble is magnified and seen in excellent lighting, making it easier to visualize in the average clinic situation. Physicians of other specialties, on witnessing a session of dermatology by television at the Medical School's Kellogg Auditorium, remarked that using color TV was better than examining the patients at first hand.

Dr. Johnson's success is part of medical history in the making at Dartmouth. Some time ago the chairman of the Medical School's Department of Psychiatry conceived the idea of conducting psychiatric onsultations by closed- circuit television and a link was established between Hanover and Claremont General Hospital. This was a great "first" at the time, though a similar link, later established in the Boston area, received national publicity as the innovator. Nevertheless, the "Claremont link," as it became known, was a success. Perhaps its apocryphal but it is repeated that in one of the early sessions the rapport between psychiatrist at Dartmouth and patient in Claremont was so neatly knit that as the consultation ended the patient stood up and, gratefully, tried to shake hands with the TV screen in front of him.

The "link" is now a network. In fact, it is the "New Hampshire/Vermont Medical Interactive Television Network," and this is the first interstate medical television network in the country. The original link was in operation when Dr. Dean J. Seibert of the Medical School faculty was named Assistant Dean for Regional Medical Affairs and, with the backing of the Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications, he established the electronic network between Dartmouth and the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington. Claremont General Hospital remains a vital part of the network and Central Vermont Medical Center in Berlin is also an important component.

At the end of this month the network will be formally dedicated, with V.I.P.-attended ceremonies at Hanover and Claremont in New Hampshire and at Berlin and Burlington in Vermont, and thus, for the first time, people across the country will become aware of the unique interstate system.

Tall and lean Dr. Seibert, who always emanates a handsome and appealing intensity whether he is on the Hanover tennis courts or arriving at the Medical School carly in the morning, has worked devotedly at developing the capabilities of the network. With his highly trained and dedicated colleagues in the School's Department of Community Medicine, he has made the network an essential daily part of medical care in New England. During a recent week well over 20 hours of scheduled TV sessions were held. The network is far more than simply an out-growth of the original psychiatry consultation link.

Now the potentials of closed-circuit television are many, and although not all of them are presently exploited by the network, the electrons transmitting images between Hanover and Burlington are doing a fine variety of jobs.

None of the TV sessions conducted at Mary Hitchcock is exactly typical, but the following suggests what the qualified visitor to Bowler Auditorium might see during the "noon conference" usually held three days a week between 12:15 and 1:15 p.m.

The audience consists of doctors, nurses and other health professionals, interns and residents. Some sit upright; some sprawl, a few eat the apples and yogurt they have had to bring with them for lunch. All are extremely attentive. The session is conducted by the medical specialist who stands center stage with a microphone before him. A pair of TV technicians work at the rear, their cameras usually trained on the small stage up front but sometimes picking up the face of a questioner in the audience. Also up front is a large television screen showing the "other audience" at Claremont, Central Vermont Medical Center, or Burlington.

The door to the auditorium opens and the patient is brought onto the small stage in a wheelchair. The specialist then discusses the patient's problems and symp- toms, and occasionally treatment, with the patient. There are often questions from the Hitchcock personnel who are actually present and almost always questions from the other audience on the TV screen. The obliging patient is then wheeled out and there is further, "interactive" discussion of the case.

Again, it should be noted that the witnessed or described television session cannot be termed "typical," for individuals are involved.

One of the consultations that seemed of unusual interest to lay observers concerned a Hanover girl who, although of high school age, was suffering temporarily from arthritis. A normally lively girl who seemed to find the wheelchair rather restricting as she answered questions put to her by her immediate audience and the one in Claremont, she was helpful in demonstrating specialist techniques at Hitchcock to general practitioners elsewhere. The patients who are the subjects of other sessions may be middle-aged residents of the villages of Vermont and New Hampshire who have peptic ulcers or elderly people with heart trouble.

The use of the medical network is by no means confined to the continuing medical education of doctors by disseminating information from specialist to generalist. It goes well beyond physician to-physician consultation. And not all the sessions originate in facilities as imposing as Bowler Auditorium on the top floor of Hitchcock. It is important for nurses in community hospitals to acquire the nur- sing know-how developed in Hanover, and nurse-to-nurse sessions occur- frequently.

Regular users of the medical network are the nurses of the Coronary Care Unit at Hitchcock and they have become so accustomed to it that they look and sound as though they were in the same room with their counterparts at other hospitals.

For obvious reasons, once they get into their subject, their talk is professionally direct and informative, but the sessions often have casual beginnings.

Seated in the cramped, glass-enclosed TV nook in the center of the hushed Coronary Care Unit, one of the Hitchcock nurses, looking generally into the camera trained on her but also glancing at the TV screen showing the scene at Claremont General, remarks, "The Dartmouth Skiway's still pretty good considering we haven't had any new snow for weeks but the skiing could be better. What we need is about ten inches of new snow."

The nurse on the screen, looking into her own camera in Claremont, replies, "It's about the same at Ascutney but we've had some skiing right along. But we do need some more snow."

Then the nurses slip quickly into intense talk about coronary patient care.

The potential of medical television extends still further, beyond doctor and nurse communication. Among the others who may use the network are nursing home personnel, welfare and social workers, planned parenthood experts. The network may expand physically, too, with extensions into New York and Maine anticipated, and will probably include additional New Hampshire and Vermont communities of varying sizes, such as Windsor and Bellows Falls.

At the moment, economy is a big factorthe use of existing electronic facilities on Mounts Ascutney, Pleasant and Mansfield permitted the establishment of the network across Vermont. Today it is not known if funds, similar to those provided by Washington for experimentally setting up the network, will be forthcoming.

The Dartmouth Medical School has faith in what it has created. "The development of this medical television system is of great importance," Dr. Kenneth G. Johnson (husband of Dr. Marie-Louise Johnson), Chairman of the Medical School's Department of Community Medicine, declared. "Through this system, the resources of medical centers can be shared with many communities. It will give the patient in a small town the benefits of modern biological science and technology. Interactive television brings community and center physicians together in an effective learning and working relationship. The potential to teach and train health professionals, allied health personnel and students without removing them from the community is without parallel in any other system of communication."

Concerning the Medical School's innovative use of television. Dr. S. Marsh Tenney, Acting Dean, said, "It is the responsibility of a medical school to experiment in new methods of delivering services as well as to educate practicing physicians. The school has the obligation to work outside its own immediate institutions, to upgrade health services at the community level and to assist practicing physicians in every feasible way."

A cluster of electronic mushrooms atopMt. Ascutney serves to relay television images and medical information betweenDartmouth-Hitchcock and the CentralVermont Medical Center located in Berlin.

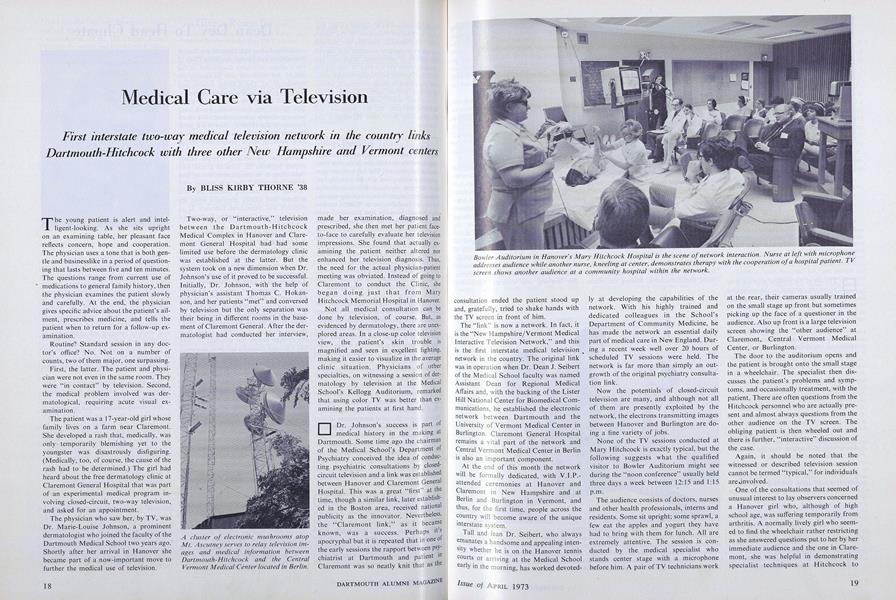

Bowler Auditorium in Hanover's Mary Hitchcock Hospital is the scene of network interaction. Nurse at left with microphoneaddresses audience while another nurse, kneeling at center, demonstrates therapy with the cooperation of a hospital patient,screen shows another audience at a community hospital within the network.

Personnel at Central Vermont Medical Center watching and listening to a physician atHitchcock Hospital in Hanover. They in turn are caught by the television camera and areseen by the speaker and audience in Hanover.

Establishment of the "New Hampshire-Vermont Medical Interactive TelevisionNetwork" has been achieved through the leadership of Dr. Dean J. Seibert (center), the Medical School's Dean for Regional Medical Affairs. With him are Harold F. Pyke Jr.,operational director of the network who is an expert in instructional technology, andMrs. Charlotte Sanborn, research associate with extensive community medicine experience. All are members of the Medical School's Department of Community Medicine-

The medical TV network is not limited to discussions between physicians. Specialistnurses in hospitals linked by the new electronic system also discuss methods and ex-periences with their counterparts in other hospitals. Seated here are nurses of theCoronary Care Unit at Claremont General Hospital. Conversing with them via the TVscreen at left are nurses of the Coronary Care Unit at Mary Hitchcock Hospital.

A map showing the link-up of the two-way, closed-circuit TVnetwork, which may grow within the two states and move into Maineand New York. The relay stations at Mts. Ascutney, Pleasant, andMansfield were established for educational TV.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGuatemalan Cane Raiser

April 1973 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureArt Carpenter

April 1973 -

Feature

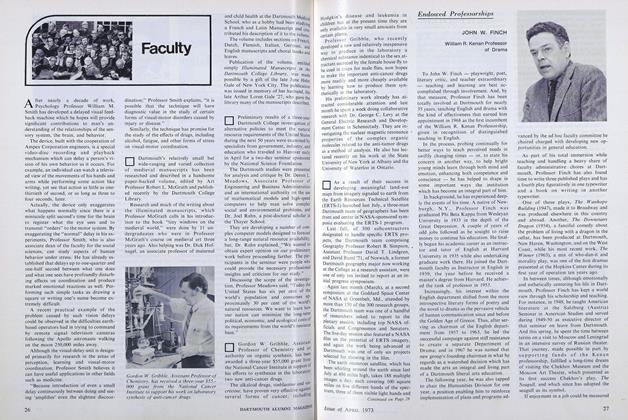

FeatureHanover Has A Mardi Gras

April 1973 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

April 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1973 By DREW NEWMAN '74 -

Article

ArticleEugen Rosenstock-Huessy

April 1973 By HAROLD STAHMER '51

BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38

-

Article

ArticleMedical School

JANUARY 1972 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

FEBRUARY 1972 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

APRIL 1972 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

MAY 1972 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

NOVEMBER 1972 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Books

BooksDARTMOUTH MEDICAL SCHOOL: THE FIRST 175 YEARS.

APRIL 1973 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePiano Man

July/August 2011 By ERIC TUCKER -

Feature

FeatureMUSIC FESTIVAL

June 1958 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureNow They're Flicks, Not Movies, But The Nugget Still Carries On

February 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dialogue Turns to Diatribe

MAY 1989 By Larry Martz '54 -

Feature

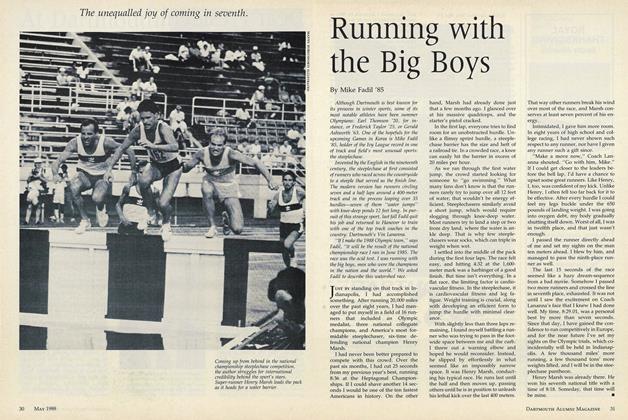

FeatureRunning with the Big Boys

MAY • 1988 By Mike Fadil '85 -

Feature

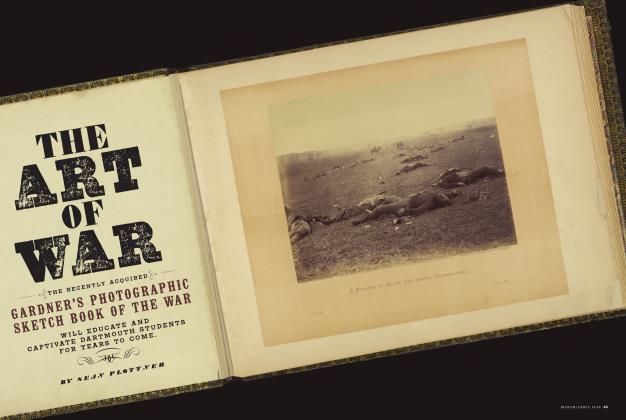

FeatureThe Art of War

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By Sean Plottner