Richard Brautigan, something of a counter-culture hero, is acontemporary author whose work is seldom analyzed inacademic courses. Richard Carvolth chose him as the subject forthis critique written for Prof. Louis Renza's course in AmericanProse.

Richard Brautigan's prose work entitled Trout Fishing inAmerica hardly seems to deserve the classification of novel which its author so carefully insists upon. It develops no extensive narrative but consists instead of a group of short, often fragmentary, and seemingly unrelated vignettes. There exist no highly developed characters, the principal one appears to be an ambiguously personified activity (Trout Fishing in America), while the personality of the narrator remains maddeningly elusive. Indeed, its very length (barely 100 pages if the abundant blank spaces were eliminated) might disqualify it from the ranks of even the shortest novels by such writers as Hemingway (whom Brautigan closely resembles in finality of tone and brevity of style). Further, it may not be perfectly clear whether the work is fact or fiction. However, Brautigan is justified in insisting upon the classification. The vignettes are closely related thematically. The elusiveness of the narrator's personality is as systematically sustained as many "normal" characters are carefully developed. And, finally, despite its autobiographical appearance, TroutFishing in America is fiction.

Throughout the book, Brautigan conceives of society as an obstacle which not only prevents individuals from self-discovery by the process of delusion but also destroys many of those who may not be deluded. The sheep entice some of the coyotes to a hideous, cyanide death and the Washington Square artists are forced to choose between the socially acceptable inanity of training fleas or condemnation to the insane asylum (which may even be preferable).

Conversely, Brautigan lauds any idiosyncratic behavior and glorifies pariahs. The Kool-Aid Wino lives in the illumination of his private "Kool-Aid reality." Charles Hayman "never had a cup of coffee, a smoke, a drink or a woman," and lived in tranquil harmony with nature disturbed by neither children nor adults. Trout Fishing in America Shorty is a glorious "wino" who, in his gruff way, loves little children for their unsocialized spontaneity and candor without giving a fig for the society, of which they will soon form the foundation (when the narrator's baby abandons him for the sandbox, "Trout Fishing in America Shorty stared after her as if the space between them were a river growing larger and larger"). In fact, the narrator would glorify Shorty's drunken tranquility and idiosyncrasy over Ben Franklin's indelible American pattern which moulds the "Boys and Girls who will soon take our places and pass on." Above all, the narrator himself, with whose keen wit, warm humor, and down-to-earth love of nature we are intended to sympathize, behaves and thinks in a highly individualistic manner. As a child he "terrorizes" the first-graders by writing "Trout Fishing in America" on their backs; later he specializes in waterbugs. He chooses Little Redfish Lake for his camping place primarily because "... those few people who were staying at the camp now, were staying there because they didn't have any sense. We joined them enthusiastically." In fact, his enthusiasm and spontaneity constitute the guiding principles of his life for he seems never to plan for the future (if he spends a year in a bookstore, his only concern with time is that eventually the year will run out) The individual for whom the narrator has perhaps the most admiration is the hunchback trout. This unique fish is inspiring'? beautiful in a peculiar fashion: "There was a fine thing about that I only wish I could have made a death mask of him. Not of his body though, but of his energy.... I had that hunchback trout for dinner ... its hump tasted sweet as the kisses of Esmeralda."

Certainly, the hunchback trout is only one of many references to trout and trout fishing in the novel. It is clear that "trout fishing in America" is an intentionally nebulous concept which is in some way central to the significance of the work. It seems to me that the phrase is the epigrammatic epitome of the author's two central and ultimately indivisible concerns: communication and consciousness. Just as the social being, for Brautigan, is a fiction or untruth (pseudo self) so too is the language of which society makes use and the consciousness which that language imposes upon the individuals who must utilize it. Language, particularly the written word, is, as Brautigan points out in the next to the last chapter, the fossil of thought. A fossil because it is static and therefore dead, whereas thought is a dynamic, forward moving, infinitely reverberating process; something to which the stasis of words can only allude.

Precisely because words are inadequate to thought, they shape and restrict thought. When I speak of an object not only do I fail to communicate the totality of my consciousness of that object, I also partially mold my consciousness into the shape of the words (and the connotations of the words) which I am using either to describe the object to others or think about privately. Thus, reality (and the true self) for Brautigan is the process of life, the expense of energy, the pure, personal unpremeditated perceptions and cognitive associations or leaps which occur without the stultifying effect of a language used to fix them in the mind of the subject or communicate them to others. The fiction, then, consists of whatever is static or permanent, and therefore dead; whatever is commonly accepted, normal, or taken for granted. By allowing the stasis of language to shape perceptions and thoughts, the individual asserts his fictional roles and denies his true being, denies his very life energy.

The evidence of Brautigan's belief in the expense of energy as the life-giving principle and in the restriction of energy as stasis and death is abundant. The narrator swims in the Worsewick Hot Springs with his woman. His spontaneous"sexual impulses are contrasted with the dead fish and stagnant slime which have life only as long as they exist in the context of the narrator's sexual act. In the orgasmic moment he is truly alive and the expense of energy, the process of "coming," cannot be fixed by speech (represented by the social institution for establishing language, the school), "Then I came, and just cleared her in a split second like an airplane in the movies, pulling out of a nosedive and sailing over the roof of a school." However, once the sperm leaves his body the sexual act is complete; the sperm drifts in the water; no longer in the process it is fixed and unites with the fish in death as the trout with "eyes stiff like iron" falls out of the narrator's consciousness and the chapter abruptly ends. In "Red Lip" Brautigan voices his characteristic condemnation of the worthlessness of monuments, '"Fuck you,' I said to the outhouse. 'All I want is a ride down the river.' " In "Footnote Chapter to Red Lip" the outhouse comes to life by serving as a disposal for the narrator's "bright, definite, and lusty garbage." Trout Fishing on the Bevel" presents two graveyards with a trout stream between them. The narrator contrasts the artificially green, apparently permanent graveyard for the rich with the wilted, abandoned death of the graveyard for the poor. However, neither setting makes any difference to its inhabitants whose poverty" (or lack of energy, or death) bothers the narrator. Indeed, the graveyards only have significance and life for the narrator as he fishes and for the reader as he experiences rautigan's attempt to convey what his mind and imagination Perceived,

... I had a vision of going over to the poor graveyard and gathering up grass and fruit jars and tin cans and markers and wilted flowers and bugs and weeds and clods and going home and putting a hook in the vise and tying a fly with all that stuff and then going outside and casting it up into the sky, watching it float over the clouds and then into the evening star.

In fact, the entire method, structure, and style of Trout Fishingin America strive, like the title, against permanence. The narrator is never clearly identified (much less given character development) because his true nature cannot be captured with words. The vignettes, or chapters, are fragments because the essence of the situations, things, places, persons, and events which they attempt to portray can only be hinted at and then abandoned for something new. There is no coherent, unified narrative because life is a process of random experiences which flash upon the individual consciousness with no ultimate purpose or goal. Nothing makes sense in and of itself but only as it participates in an individual's consciousness. That is, all things, perse, are equally absurd, but the acts of consciousness they stimulate are real (until the process of those acts has become fossilized by language into just another static object). Thus, the reification of the normal conception of things is the grandest absurdity. The leap of the imagination from trout stream to telephone booths is what is real and alive. Society and language fossilize the mind by habit but if one looks closely at the puddles he may find waterbugs carrying newspapers. The narrator refuses to be fossilized. He sees a woodcock with "... a long bill like putting a fire hydrant into a pencil sharpener, then pasting it onto a bird and letting the bird fly away in front of me with this thing on its face for no other purpose than to amaze me." Even the laws of the physical universe cannot bound the mental tide of the energy which constitutes his true being. If he finds himself in a bookstore in the fantastic posture of "laying" a girl who is "... a clear mountain river of skin and muscle flowing over rocks of bone and hidden nerves," he could just as well have been doing all the equally fantastic (and, thus, equally real when given life in the mind) things the owner of the store relates. Thus, Brautigan's fantastic and (we might say) absurd stories, his abnormal cognitive associations, his abrupt transitions and endings, his images which twist and explode "like a telescope in an earthquake," and his helter-skelter juxtapositions of words, images, and chapters exist in an effort to reflect or at least intimate the unbounded flow of energy which constitutes his true being.

Furthermore, the central image and symbol of the novel is a process. Trout Fishing in America intimates (since that is all words may do) the process of fishing for trout in America, but it also represents the fact that reality in general and the true self are processes. Trout Fishing in America is the personification of the essence of process whether it be fishing or dancing or playing with babies by the river, or searching for self or even mistaking the self. It is the antithesis of stasis. Thus, the reason for Brautigan's ambiguous portrayal of Trout Fishing in America should be clear. He may treat it as a person or as an activity, he may place it in any situation, he may put words in its mouth, he may kill its personification or he may revive it, but he cannot clearly define it. Like the narrator's true being, Trout Fishing in America defies expression and exists only as long as it is an unspecified expense of energy. The narrator becomes a "terrorist" by defying the stasis for which society (the school) longs. The first-graders cannot see the Trout Fishing in America on their own backs yet they cannot escape it. They mistake their essence for the permanence of the swings and are taught to ignore their true beings which the narrator recognizes as "quite natural and pleasing to the eye." Society deludes individuals into conceiving of themselves as a set of consistent, permanent roles, attitudes, and beliefs. Pard indicates that the man wanted by the F. B.I, is guilty only of being "an avid trout fisherman." On the other hand, the F. B.I, agents are trained to regard everything as a computer punchout and to take whatever shape the sun dictates. Their mistake is to identify with the shape rather than the change, with the holes in the card rather than the punching of it.

Hotel Trout Fishing in America is an everchanging place thanks to the Chinese who manage it. It is also an absurd and incongruous place where normal logic and behavior are suspended but where the narrator discovers the meaning of 208. By contrast, Trout Fishing in America finds New York unbearable because it is full of dogs (the domestic animal) and Puerto Ricans and, ultimately the hot, close, stifling death society produces in the individuals who succumb to it. He longs for the cool, clear flowing streams of Alaska. When the young narrator imagines trout to besteel he reflects his society's power to project its ideals of progress and power onto every aspect of life. The child's consciousness is shaped by society so that instead of the energy and beauty of the trout he sees the stasis of metal, and longs for that permanence. But Trout Fishing in America "recalls with amusement" other mistaken Americans with different and older ideals and a different, but no less static consciousness. Later the child realizes his error. He becomes aware that what looks like a trout stream from a distance might look like a stairway when one approaches and scrutinizes it. He realizes that his desires and thoughts have dictated to his perceptions and have deceived him so he resolves to "become his own trout" and scrutinize his consciousness. Of course, Trout Fishing in America is helpless because the child must discover that life, reality, and consciousness are processes; the objects themselves cannot be changed (even by Trout Fishing in America) nor can they reveal the truth. The child must 'discover himself by fishing and must learn not to impose his conception or society's conception (by way of language) upon reality.

Significantly, the next chapter ("Red Lip") finds the narrator, seventeen years later, on a fishing trip, idly hitch-hiking and playing a game with flies ("It was something to do with my mind") and denouncing the stasis of the outhouse monument. Further, it appears that Alonso Hagen never caught trout because he was so intent upon it. His consciousness was so fixed upon the physical aspect of trout that he could never understand that the reality is the process of fishing. The self is to be found not by catching so many fish but rather by engaging in fishing. Similarly, Trout Fishing in America dies ("Autopsy of Trout Fishing in America") when it is treated as an object and its parts are analyzed and defined. But it only dies in the moment that the consciousness imposes the limits of time and place upon it. It can easily be revived by recognizing it as an unending and unspecified (with respect to time, place, manner, method, and above all consciousness of the fisherman) expense of energy.

A provoking question immediately arises: "If reality is the process or the expense of energy, must not the specific entities without which no process would exist, also be real?" Brautigan indicates, I believe, that the specific entities are all equally real or equally unreal and therefore unimportant except in their capacity as elements of the process. Trout must exist in order for trout fishing in America to exist. Trout entice anglers, escape their hooks, fight back, and even go as far as to "chop off" Trout Fishing in America Shorty's legs. However, which particular trout participate in the process of which event is unimportant. The ballet dancers in "The Ballet for Trout Fishing in America" "hold our imaginations in their feet" only in so far as they are dancing, and dancing in Los Angeles at the University of California. Clearly, our imaginations (consciousness) cannot be bound by the dancers for the energy of the ballet stems from "How the Cobra Lily traps insects." Consciousness traps and utilizes specific perceptions and ideas but is not confined to nor defined by them. Purely imaginary events (such as the bookstore owner's tales) are as real (or as fictional) as actual events in the physical world. However, the-expense of energy remains the same. Thus, paradoxically it is the process of consciousness which is the permanent reality (and the true self) while the specific (but interchangeable) physical and mental events which form the fodder are all equally and fleetingly real.

The ballet dancers who "hold our imaginations in their feet" indicate Brautigan's self-conscious attempt to intimate the permanence of process by portraying the transitory nature of the specific. Brautigan draws attention to Trout Fishing in America as a literary work precisely because he wishes to demonstrate the failure of the very medium he must use. Language cannot deliver the essence of process because words fossilize images and ideas. One may at best talk around Trout Fishing in America or the "I" of the narrator. "Grider Creek" produces only a map of the real creek which "Prologue to Grider Creek" seems to promise. Significantly, the concluding chapter fails to produce the "mayonnaise" promised .in "Prologue to the Mayonnaise Chapter": "Sorry I forgot to give you the mayonaise" (mayonnaise misspelled). Clearly, Brautigan has not forgotten but rather is unable to state the reality. Further, the cover of the book is a recurring motif. Sometimes it is "five o'clock in the afternoon of" the cover, sometimes it is early morning, sometimes the narrator is alone at the scene of the cover, sometimes he is accompanied by his woman and baby and Trout Fishing in America Shorty, at other times he is accompanied by the poor, or by his "wino" friends. Indeed, the photograph which constitutes the cover only intimates the actuality it represents.

What, then, is the motive for Brautigan's writing a book whose language must inevitably fail its author's purpose? There are, I think, three possible reasons. In the first place, it might be argued that to hint at reality is better than not to hint at it, if it is the case that reality may not be stated. Further, the act of writing is, for the author, a self-creative process, an expense of energy like any other act of consciousness; despite the fact that Brautigan as author (i.e. having written) is a fossil of the true being and the narrator an even remoter one. Finally, the specific images and ideas may participate in the reader's flow of consciousness and may, indeed hopefully will, display their own fleetingness and interchangeability and in so doing suggest the permanence of the overriding process.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSailing Dreams and Random Thoughts

March 1973 By JAMES H. OLSTAD '70 -

Feature

FeatureNotes Towards a "Whole Life Catalog"

March 1973 By ALAN T. GAYLORD, DIRECTOR -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

March 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

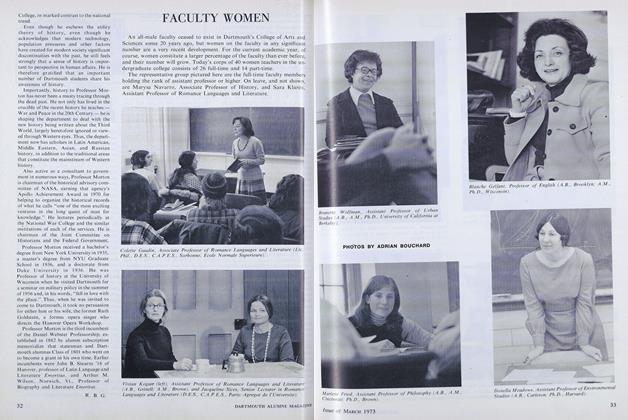

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

March 1973 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL

March 1973 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Days—60 Years Ago

March 1973 By Leslie W. Leavitt '16

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE SECOND NATIONAL POW WOW CHICAGO, NOV. 23-24, 1928

MARCH, 1928 -

Article

ArticleCouncil Member

December 1938 -

Article

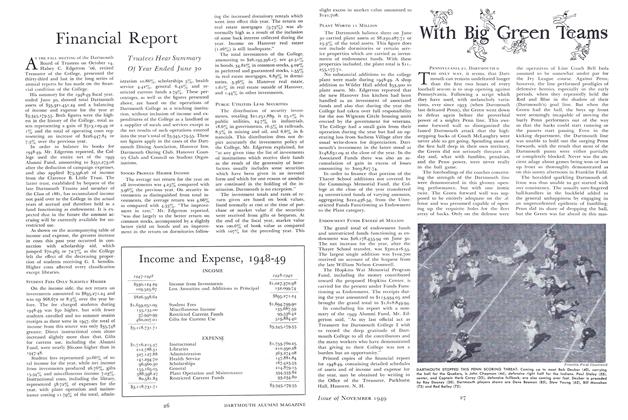

ArticleFinancial Report

November 1949 -

Article

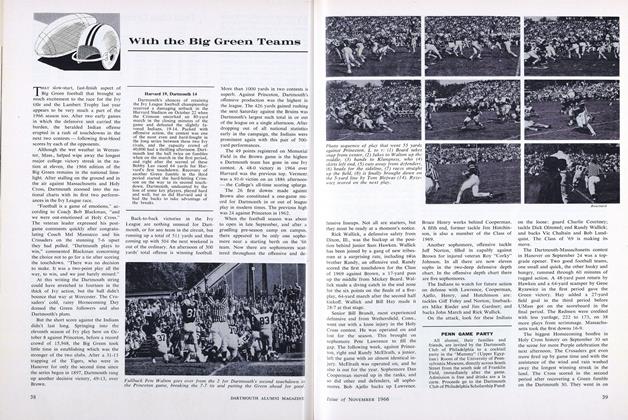

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

NOVEMBER 1966 -

Article

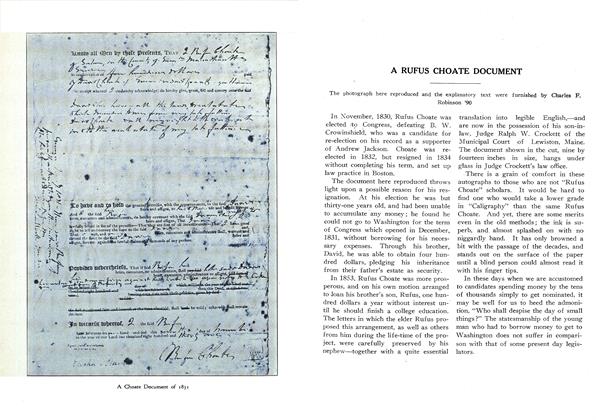

ArticleA RUFUS CHOATE DOCUMENT

April, 1923 By Charles F. Robinson '90 -

Article

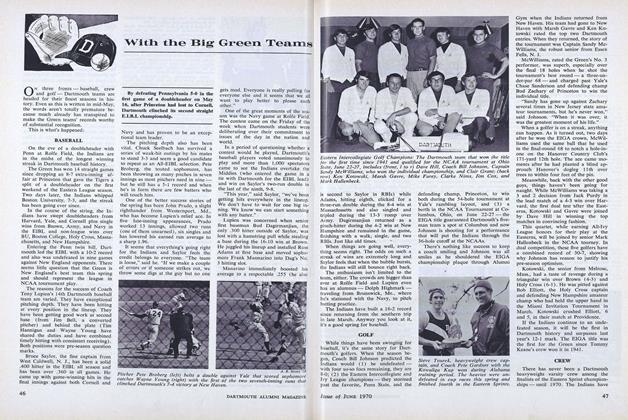

ArticleBASEBALL

JUNE 1970 By JACK DEGANGE