He calls himself "a maker of things."

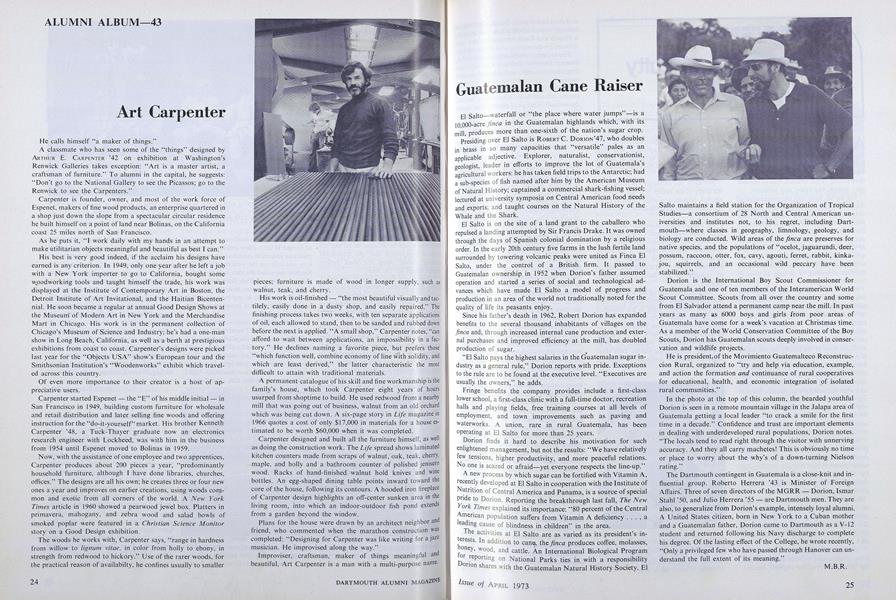

A classmate who has seen some of the "things" designed by ARTHUR E. CARPENTER '42 on exhibition at Washington's Renwick Galleries takes exception: "Art is a master artist, a craftsman of furniture." To alumni in the capital, he suggests: "Don't go to the National Gallery to see the Picassos; go to the Renwick to see the Carpenters."

Carpenter is founder, owner, and most of the work force of Espenet, makers of fine wood products, an enterprise quartered in a shop just down the slope from a spectacular circular residence he built himself on a point of land near Bolinas, on the California coast 25 miles north of San Francisco.

As he puts it, "I work daily with my hands in an attempt to make utilitarian objects meaningful and beautiful as best I can."

His best is very good indeed, if the acclaim his designs have earned is any criterion. In 1949, only one year after he left a job with a New York importer to go to California, bought some woodworking tools and taught himself the trade, his work was displayed at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the Detroit Institute of Art Invitational, and the Haitian Bicentennial. He soon became a regular at annual Good Design Shows at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Merchandise Mart in Chicago. His work is in the permanent collection of Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry; he's had a one-man show in Long Beach, California, as well as a berth at prestigious exhibitions from coast to coast. Carpenter's designs were picked last year for the "Objects USA" show's European tour and the Smithsonian Institution's "Woodenworks" exhibit which traveled across this country.

Of even more importance to their creator is a host of ap- preciative users.

Carpenter started Espenet - the "E" of his middle initial - in San Francisco in 1949, building custom furniture for wholesale and retail distribution and later selling fine woods and offering instruction for the "do-it-yourself" market. His brother Kenneth Carpenter '48, a Tuck-Thayer graduate now an electronics research engineer with Lockheed, was with him in the business from 1954 until Espenet moved to Bolinas in 1959.

Now, with the assistance of one employee and two apprentices, Carpenter produces about 200 pieces a year, "predominantly household furniture, although I have done libraries, churches, offices." The designs are all his own; he creates three or four new ones a year and improves on earlier creations, using woods com- mon and exotic from all corners of the world. A New YorkTimes article in 1960 showed a pearwood jewel box. Platters in primavera, mahogany, and zebra wood and salad bowls of smoked poplar were featured in a Christian Science Monitor story on a Good Design exhibition.

The woods he works with, Carpenter says, "range in hardness from willow to lignum vitae, in color from holly to ebony, in strength from redwood to hickory." Use of the rarer woods, for the practical reason of availabilty, he confines usually to smaller pieces; furniture is made of wood in longer supply, such as walnut, teak, and cherry.

His work is oil-finished - "the most beautiful visually and tactilely, easily done in a dusty shop, and easily repaired." The finishing process takes two weeks, with ten separate applications of oil, each allowed to stand, then to be sanded and rubbed down before the next is applied. "A small shop," Carpenter notes, "can afford to wait between applications, an impossibility in a factory." He declines naming a favorite piece, but prefers those "which function well, combine economy of line with solidity, and which are least derived," the latter characteristic the most difficult to attain with traditional materials.

A permanent catalogue of his skill and fine workmanship is the family's house, which took Carpenter eight years of hours usurped from shoptime to build. He used redwood from a nearby mill that was going out of business, walnut from an old orchard which was being cut down. A six-page story in Life magazine in 1966 quotes a cost of only $17,000 in materials for a house estimated to be worth $60,000 when it was completed.

Carpenter designed and built all the furniture himself, as well as doing the construction work. The Life spread shows laminated kitchen counters made from scraps of walnut, oak, teak, cherry, maple, and holly and a bathroom counter of polished jenisero wood. Racks of hand-finished walnut hold knives and wine bottles. An egg-shaped dining table points inward toward the core of the house, following its contours. A hooded iron fireplace of Carpenter design highlights an off-center sunken area in the living room, into which an indoor-outdoor fish pond extends from a garden beyond the window.

Plans for the house were drawn by an architect neighbor and friend, who commented when the marathon construction was completed: "Designing for Carpenter was like writing for a jazz musician. He improvised along the way."

Improviser, craftsman, maker of things meaningful and beautiful, Art Carpenter is a man with a multi-purpose name.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMedical Care via Television

April 1973 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Feature

FeatureGuatemalan Cane Raiser

April 1973 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureHanover Has A Mardi Gras

April 1973 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

April 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1973 By DREW NEWMAN '74 -

Article

ArticleEugen Rosenstock-Huessy

April 1973 By HAROLD STAHMER '51

Features

-

Feature

FeatureGeorge Nickum '31 to Head Alumni Council for 1956-57

July 1956 -

Feature

FeatureTimbers Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1969 -

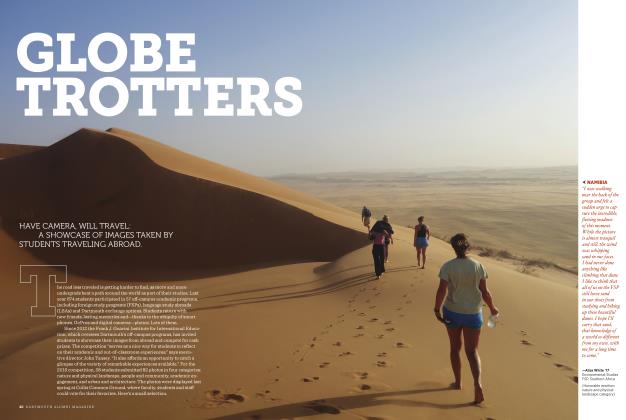

FEATURE

FEATUREGlobe Trotters

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 -

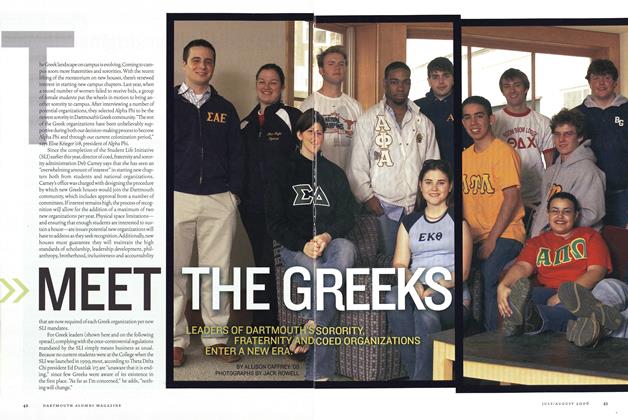

Feature

FeatureMeet the Greeks

July/August 2006 By ALLISON CAFFREY ’06 -

Feature

Feature"Intensive" Is the Word for It

MARCH 1968 By Joan Hier -

Feature

FeatureMore Dividends Than Expected

OCTOBER 1967 By MARION BLYTH