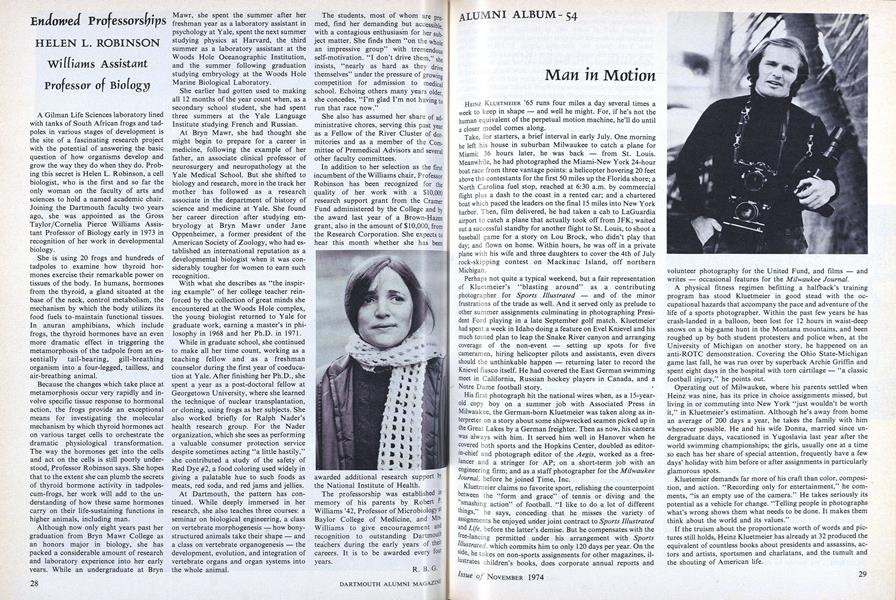

HEINZ KLUETMEIER '65 runs four miles a day several times a week to keep in shape - and well he might. For, if he's not the human equivalent of the perpetual motion machine, he'll do until a closer model comes along.

Take, for starters, a brief interval in early July. One morning he left his house in suburban Milwaukee to catch a plane for Miami; 36 hours later, he was back - from St. Louis. Meanwhile, he had photographed the Miami-New York 24-hour boat race from three vantage points: a helicopter hovering 20 feet above the contestants for the first 50 miles up the Florida shore; a North Carolina fuel stop, reached at 6:30 a.m. by commercial flight plus a dash to the coast in a rented car; and a chartered boat which paced the leaders on the final 15 miles into New York harbor. Then, film delivered, he had taken a cab to LaGuardia airport to catch a plane that actually took off from JFK; waited out a successful standby for another flight to St. Louis, to shoot a baseball game for a story on Lou Brock, who didn't play that day; and flown on home. Within hours, he was off in a private plane with his wife and three daughters to cover the 4th of July rock-skipping contest on Mackinac Island, off northern Michigan.

Perhaps not quite a typical weekend, but a fair representation of Kluetmeier's "blasting around" as a contributing photographer for Sports Illustrated - and of the minor frustrations of the trade as well. And it served only as prelude to other summer assignments culminating in photographing Presi- dent Ford playing in a late September golf match. Kluetmeier had spent a week in Idaho doing a feature on Evel Knievel and his much touted plan to leap the Snake River canyon and arranging coverage of the non-event - setting up spots for five cameramen, hiring helicopter pilots and assistants, even divers should the unthinkable happen - returning later to record the Knievel fiasco itself. He had covered the East German swimming meet in California, Russian hockey players in Canada, and a Notre Dame football story.

His first photograph hit the national wires when, as a 15-yearold copy boy on a summer job with Associated Press in Milwaukee, the German-born Kluetmeier was taken along as interpreter on a story about some shipwrecked seamen picked up in the Great Lakes by a German freighter. Then as now, his camera was always with him. It served him well in Hanover when he covered both sports and the Hopkins Center, doubled as editor-in-chief and photograph editor of the Aegis, worked as a free-lancer and a stringer for AP; on a short-term job with an engineering firm; and as a staff photographer for the MilwaukeeJournal, before he joined Time, Inc.

Kluetmeier claims no favorite sport, relishing the counterpoint between the "form and grace" of tennis or diving and the smashing action" of football. "I like to do a lot of different things,' he says, conceding that he misses the variety of assignments he enjoyed under joint contract to Sports Illustratedand Life, before the latter's demise. But he compensates with the free"lancing permitted under his arrangement with SportsIllustrated, which commits him to only 120 days per year. On the side, he takes on non-sports assignments for other magazines, illustrates children's books, does corporate annual reports and volunteer photography for the United Fund, and films - and writes - occasional features for the Milwaukee Journal.

A physical fitness regimen befitting a halfback's training program has stood Kluetmeier in good stead with the occupational hazards that accompany the pace and adventure of the life of a sports photographer. Within the past few years he has crash-landed in a balloon, been lost for 12 hours in waist-deep snows on a big-game hunt in the Montana mountains, and been roughed up by both student protesters and police when, at the University of Michigan on another story, he happened on an anti-ROTC demonstration. Covering the Ohio State-Michigan game last fall, he was run over by superback Archie Griffin and spent eight days in the hospital with torn cartilage - "a classic football injury," he points out.

Operating out of Milwaukee, where his parents settled when Heinz was nine, has its price in choice assignments missed, but living in or commuting into New York "just wouldn't be worth it," in Kluetmeier's estimation. Although he's away from home an average of 200 days a year, he takes the family with him whenever possible. He and his wife Donna, married since undergraduate days, vacationed in Yugoslavia last year after the world swimming championships; the girls, usually one at a time so each has her share of special attention, frequently have a few days' holiday with him before or after assignments in particularly glamorous spots.

Kluetemier demands far more of his craft than color, composition, and action. "Recording only for entertainment," he comments, "is an empty use of the camera." He takes seriously its potential as a vehicle for change. "Telling people in photographs what's wrong shows them what needs to be done. It makes them think about the world and its values."

If the truism about the proportionate worth of words and pictures still holds, Heinz Kluetmeier has already at 32 produced the equivalent of countless books about presidents and assassins, actors and artists, sportsmen and charlatans, and the tumult and the shouting of American life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: Food for Thought

November 1974 By MICHAEL STUART -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

November 1974 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

FeatureYou Can Go Home Again

November 1974 By DICK REDINGTON '64 -

Feature

Feature"ring O bells!"

November 1974 By ELIZABETH F. MOORE -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1974 By JACK DtGANGE -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

November 1974 By J.H.