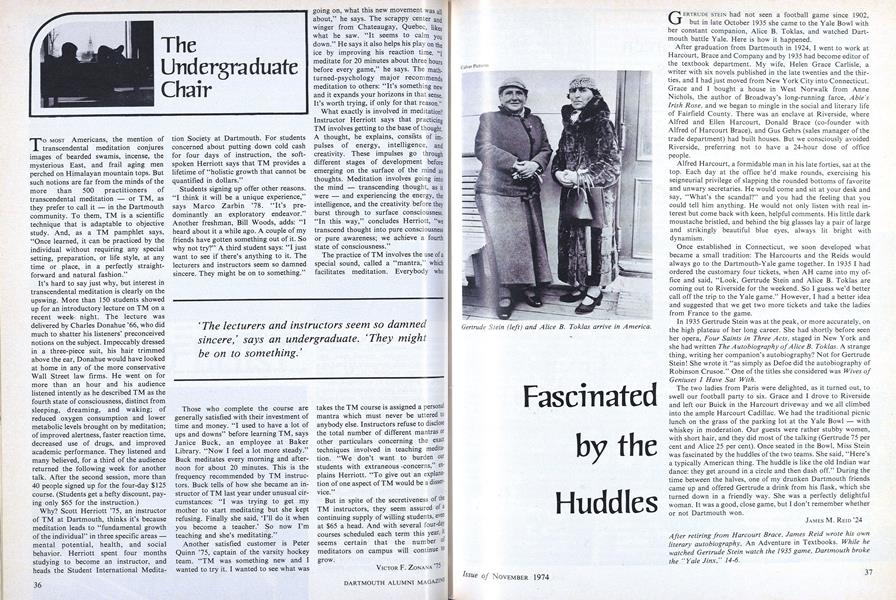

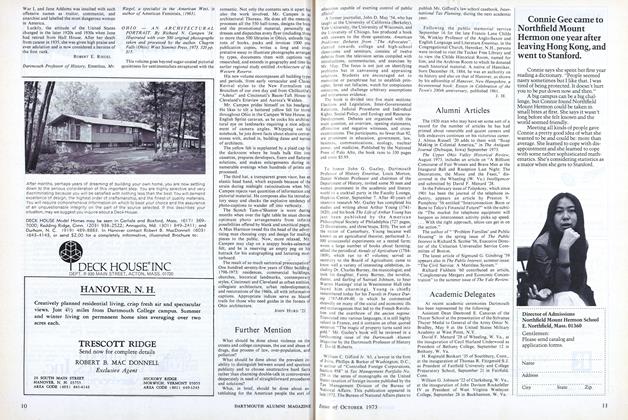

To MOST Americans, the mention of transcendental meditation conjures images of bearded swamis, incense, the mysterious East, and frail aging men perched on Himalayan mountain tops. But such notions are far from the minds of the more than 500 practitioners of transcendental meditation - or TM, as they prefer to call it - in the Dartmouth community. To them, TM is a scientific technique that is adaptable to objective study. And, as a TM pamphlet says, "Once learned, it can be practiced by the individual without requiring any special setting, preparation, or life style, at any time or place, in a perfectly straight-forward and natural fashion."

It's hard to say just why, but interest in transcendental meditation is clearly on the upswing. More than 150 students showed up for an introductory lecture on TM on a recent week night. The lecture was delivered by Charles Donahue '66, who did much to shatter his listeners' preconceived notions on the subject. Impeccably dressed in a three-piece suit, his hair trimmed above the ear, Donahue would have looked at home in any of the more conservative Wall Street law firms. He went on for more than an hour and his audience listened intently as he described TM as the fourth state of consciousness, distinct from sleeping, dreaming, and waking; of reduced oxygen consumption and lower metabolic levels brought on by meditation; of improved alertness, faster reaction time, decreased use of drugs, and improved academic performance. They listened and many believed, for a third of the audience returned the following week for another talk. After the second session, more than 40 people signed up for the four-day $125 course. (Students get a hefty discount, paying only $65 for the instruction.)

Why? Scott Herriott '75, an instructor of TM at Dartmouth, thinks it's because meditation leads to "fundamental growth of the individual" in three specific areas mental potential, health, and social behavior. Herriott spent four months studying to become an instructor, and heads the Student International Meditation Society at Dartmouth. For students concerned about putting down cold cash for four days of instruction, the soft-spoken Herriott says that TM provides a lifetime of "holistic growth that cannot be quantified in dollars."

Students signing up offer other reasons. "I think it will be a unique experience," says Marco Zarbin '78. "It's predominantly an exploratory endeavor." Another freshman, Bill Woods, adds: "I heard about it a while ago. A couple of my friends have gotten something out of it. So why not try?" A third student says: "I just want to see if there's anything to it. The lecturers and instructors seem so damned sincere. They might be on to something."

Those who complete the course are generally satisfied with their investment of time and money. "I used to have a lot of ups and downs" before learning TM, says Janice Buck, an employee at Baker Library. "Now I feel a lot more steady." Buck meditates every morning and afternoon for about 20 minutes. This is the frequency recommended by TM instructors Buck tells of how she became an instructor of TM last year under unusual circumstances: "I was trying to get my mother to start meditating but she kept refusing. Finally she said, 'I'll do it when you become a teacher.' So now I'm teaching and she's meditating."

Another satisfied customer is Peter Quinn '75, captain of the varsity hockey team. "TM was something new and I wanted to try it. I wanted to see what was going on, what this new movement was all about," he says. The scrappy center and winger from Chateaugay, Quebec, likes what he saw. "It seems to calm you down." He says it also helps his play on the ice by improving his reaction time, "I meditate for 20 minutes about three hours before every game," he says. The math-turned-psychology major recommends meditation to others: "It's something new and it expands your horizons in that sense. It's worth trying, if only for that reason."

What exactly is involved in meditation? Instructor Herriott says that practicing TM involves getting to the base of thought. A thought, he explains, consists of impulses of energy, intelligence, and creativity. These impulses go through different stages of development before emerging on the surface of the mind as thoughts. Meditation involves going into the mind - transcending thought, as it were - and experiencing the energy, the intelligence, and the creativity before they burst through to surface consciousness. "In this way," concludes Herriott, "we transcend thought into pure consciousness or pure awareness; we achieve a fourth state of consciousness."

The practice of TM involves the use of a special sound, called a "mantra," which facilitates meditation. Everybody who takes the TM course is assigned a personal mantra which must never be uttered to anybody else. Instructors refuse to disclose the total number of different mantras or other particulars concerning the exact techniques involved in teaching meditation. "We don't want to burden our students with extraneous concerns," explains Herriott. "To give out an explanation of one aspect of TM would be a disservice."

But in spite of the secretiveness of the TM instructors, they seem assured of a continuing supply of willing students, even at $65 a head. And with several four-day courses scheduled each term this year. it seems certain that the number of meditators on campus will continue to grow.

'The lecturers and instructors seem so damnedsincere,' says an undergraduate. 'They mightbe on to something.'

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: Food for Thought

November 1974 By MICHAEL STUART -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

November 1974 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

FeatureYou Can Go Home Again

November 1974 By DICK REDINGTON '64 -

Feature

Feature"ring O bells!"

November 1974 By ELIZABETH F. MOORE -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1974 By JACK DtGANGE -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

November 1974 By J.H.