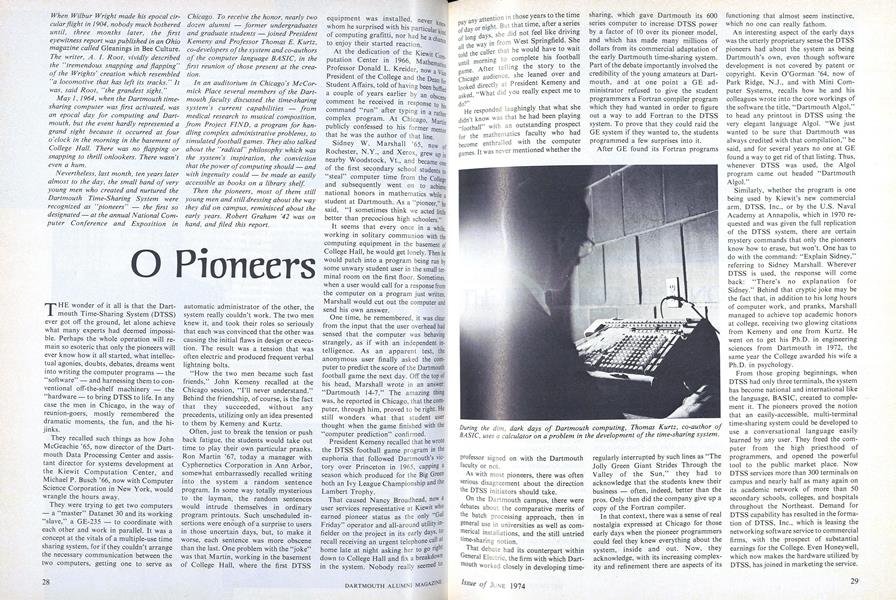

THE wonder of it all is that the Dartmouth Time-Sharing System (DTSS) ever got off the ground, let alone achieve what many experts had deemed impossible. Perhaps the whole operation will remain so esoteric that only the pioneers will ever know how it all started, what intellectual agonies, doubts, debates, dreams went into writing the computer programs - the "software" - and harnessing them to conventional off-the-shelf machinery - the "hardware - to bring DTSS to life. In any case the men in Chicago, in the way of reunion-goers, mostly remembered the dramatic moments, the fun, and the hijinks.

They recalled such things as how John McGeachie '65, now director of the Dartmouth Data Processing Center and assistant director for systems development at the Kiewit Computation Center, and Michael P. Busch '66, now with Computer Science Corporation in New York, would wrangle the hours away.

They were trying to get two computers - a "master" Datanet 30 and its working "slave," a GE-235 - to coordinate with each other and work in parallel. It was a concept at the vitals of a multiple-use time sharing system, for if they couldn't arrange the necessary communication between the two computers, getting one to serve as automatic administrator of the other, the system really couldn't work. The two men knew it, and took their roles so seriously that each was convinced that the other was causing the initial flaws in design or execution. The result was a tension that was often electric and produced frequent verbal lightning bolts.

"How the two men became such fast friends," John Kemeny recalled at the Chicago session, "I'll never understand." Behind the friendship, of course, is the fact that they succeeded, without any precedents, utilizing only an idea presented to them by Kemeny and Kurtz.

Often, just to break the tension or push back fatigue, the students would take out time to play their own particular pranks. Ron Martin '67, today a manager with Cyphernetics Corporation in Ann Arbor, somewhat embarrassedly recalled writing into the system a random sentence program. In some way totally mysterious to the layman, the random sentences would intrude themselves in ordinary program printouts. Such unscheduled insertions were enough of a surprise to users in those uncertain days, but, to make it worse, each sentence was more obscene than the last. One problem with the "joke" was that Martin, working in the basement of College Hall, where the first DTSS equipment was installed, never knew whom he surprised with his particular kind of computing grafitti, nor had he a chance to enjoy their started reaction.

At the dedication of the Kiewit Computation Center in 1966, Mathematics Professor Donald L. Kreider, now a Vice President of the College and the Dean for Student Affairs, told of having been baffled a couple of years earlier by an obscene comment he received in response to his command "run" after typing in a rather complex program. At Chicago, Martin publicly confessed to his former mentor that he was the author of that line.

Sidney W. Marshall '65, now . of Rochester, N.Y., and Xerox, grew up in nearby Woodstock, Vt., and became one of the first secondary school students to "steal" computer time from the College and subsequently went on to achieve national honors in mathematics while a student at Dartmouth. As a "pioneer," he said, "I sometimes think we acted little better than precocious high schoolers."

It seems that every once in a while working in solitary communion with the computing equipment in the basement of College Hall, he would get lonely. Then he would patch into a program being run by some unwary student user in the small terminal room on the first floor. Sometimes, when a user would call for a response from the computer on a program just written Marshall would cut out the computer and send his own answer.

One time, he remembered, it was clear from the input that the user overhead had sensed that the computer was behaving strangely, as if with an independent intelligence. As an apparent test, the anonymous user finally asked the computer to predict the score of the Dartmouth football game the next day. Off the top of his head, Marshall wrote in an answer:

"Dartmouth 14-7." The amazing thing was, he reported in Chicago, that the computer, through him, proved to be right. He still wonders what that student user thought when the game finished with the "computer prediction" confirmed.

President Kemeny recalled that he wrote the DTSS football game program in the euphoria that followed Dartmouth's victory over Princeton in 1965, capping a season which produced for the Big Greer, both an Ivy League Championship and Lambert Trophy.

That caused Nancy Broadhead, now a user services representative at Kiewit who earned pioneer status as the only "Gal Friday" operator and all-around utility infielder on the project in its early days. to recall receiving an urgent telephone call at home late at night asking her to go right down to College Hall and fix a breakdown in the system. Nobody really seemed to pay any attention in those years to the time of day or night. But that time, after a series of long days, she did not feel like driving all the way in from West Springfield. She told the caller that he would have to wait until morning to complete his football game. After telling the story to the Chicago audience, she leaned over and looked directly at President Kemeny and asked "What did you really expect me to do?"

He responded laughingly that what she didn't know was that he had been playing "football" with an outstanding prospect for the mathematics faculty who had become enthralled with the computer games. It was never mentioned whether the professor signed on with the Dartmouth faculty or not.

As with most pioneers, there was often serious disagreement about the direction the DTSS initiators should take.

On the Dartmouth campus, there were debates about the comparative merits of the batch processing approach, then in general use in universities as well as com installations, and the still untried time-sharing notion.

That debate had its counterpart within General Electric, the firm with which Dartmouth worked closely in developing time-sharing, which gave Dartmouth its 600 series computer to increase DTSS power by a factor of 10 over its pioneer model, and which has made many millions of dollars from its commercial adaptation of the early Dartmouth time-sharing system. Part of the debate importantly involved the credibility of the young amateurs at Dartmouth, and at one point a GE administrator refused to give the student programmers a Fortran compiler program which they had wanted in order to figure out a way to add Fortran to the DTSS system. To prove that they could raid the GE system if they wanted to, the students programmed a few surprises into it.

After GE found its Fortran programs regularly interrupted by such lines as "The Jolly Green Giant Strides Through the Valley of the Sun," they had to acknowledge that the students knew their business - often, indeed, better than the pros. Only then did the company give up a copy of the Fortran compiler.

In that context, there was a sense of real nostalgia expressed at Chicago for those early days when the pioneer programmers could feel they knew everything about the system, inside and out. Now, they acknowledge, with its increasing complexity and refinement there are aspects of its functioning that almost seem instinctive, which no one can really fathom.

An interesting aspect of the early days was the utterly proprietary sense the DTSS pioneers had about the system as being Dartmouth's own, even though software development is not covered by patent or copyright. Kevin O'Gorman '64, now of Park Ridge, N.J., and with Mini Computer Systems, recalls how he and his colleagues wrote into the core workings of the software the title, "Dartmouth Algol," to head any printout in DTSS using the very elegant language Algol. "We just wanted to be sure that Dartmouth was always credited with that compilation," he said, and for several years no one at GE found a way to get rid of that listing. Thus, whenever DTSS was used, the Algol program came out headed "Dartmouth Algol."

Similarly, whether the program is one being used by Kiewit's new commercial arm, DTSS, Inc., or by the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, which in 1970 requested and was given the full replication of the DTSS system, there are certain mystery commands that only the pioneers know how to erase, but won't. One has to do with the command: "Explain Sidney," referring to Sidney Marshall. Wherever DTSS is used, the response will come back: "There's no explanation for Sidney." Behind that cryptic joke may be the fact that, in addition to his long hours of computer work, and pranks, Marshall managed to achieve top academic honors at college, receiving two glowing citations from Kemeny and one from Kurtz. He went on to get his Ph.D. in engineering sciences from Dartmouth in 1972, the same year the College awarded his wife a Ph.D. in psychology.

From those groping beginnings, when DTSS had only three terminals, the system has become national and international like the language, BASIC, created to complement it. The pioneers proved the notion that an easily-accessible, multi-terminal time-sharing system could be developed to use a conversational language easily learned by any user. They freed the computer from the high priesthood of programmers, and opened the powerful tool to the public market place. Now DTSS services more than 300 terminals on campus and nearly half as many again on its academic network of more than 50 secondary schools, colleges, and hospitals throughout the Northeast. Demand for DTSS capability has resulted in the formation of DTSS, Inc., which is leasing the networking software service to commercial firms, with the prospect of substantial earnings for the College. Even Honeywell, which now makes the hardware utilized by DTSS, has joined in marketing the service.

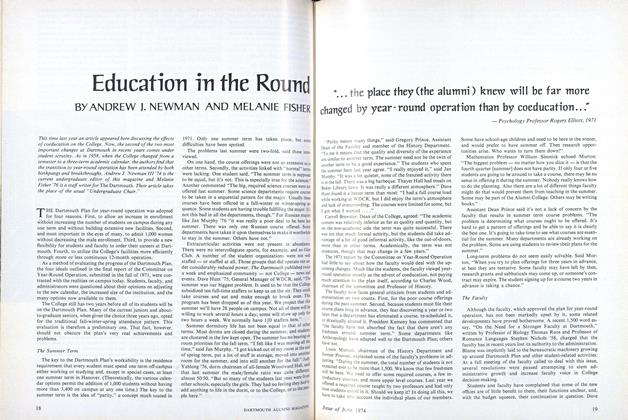

During the dim, dark days of Dartmouth computing, Thomas Kurtz, co-author ofBASIC, uses a calculator on a problem in the development of the time-sharing system.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEducation in the Round

June 1974 By ANDREW J. NEWMAN AND MELANIE FISHER -

Feature

FeatureChina's Barefoot Doctors

June 1974 By PETER KONG-MING NEW AND MARY LOUIE NEW -

Feature

FeatureCASTLES ON THE CONNECTICUT

June 1974 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

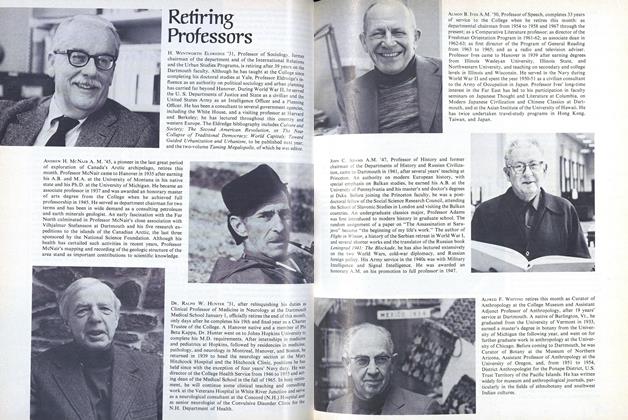

FeatureRetiring Professors

June 1974 -

Article

ArticleRetirement: Plan It and Enjoy

June 1974 By RICHARD S. BURKE '29 -

Article

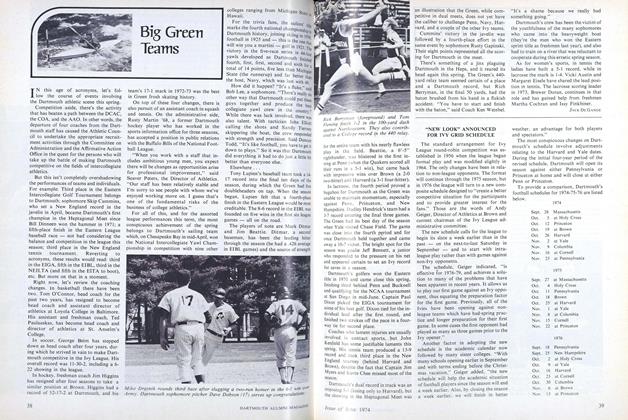

ArticleBig Green Teams

June 1974 By JACK DE GANGE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1956 -

Feature

FeatureON THE AIR 16 Hours a Day

May 1954 By DONALD R. MELTZER '54 -

Feature

FeatureSecond Panel Discussion

October 1951 By EDGAR W. McINNIS -

Feature

FeatureTelling Another's Tale

May 1981 By Gregory Rabassa -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO MAKE A GOAL KICK

Sept/Oct 2001 By KRISTIN LUCKENBILL '01 -

Feature

FeatureLet There Be Color

May/June 2013 By Sean Plottner