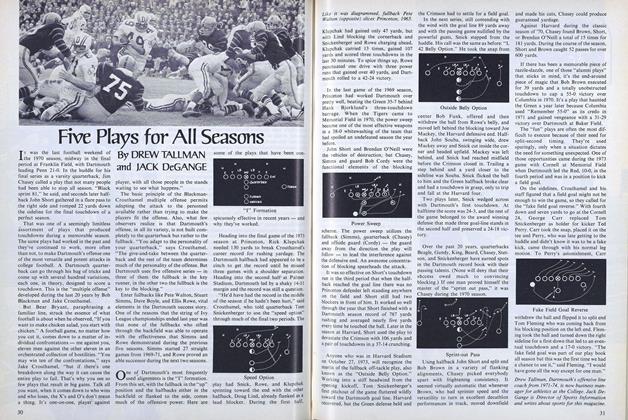

It was the last football weekend of the 1970 season, midway in the final period at Franklin Field, with Dartmouth leading Penn 21-0. In the huddle for his final series as a varsity quarterback, Jim Chasey called a play that not many people had been able to stop all season. "Black sprint 81," he said, and seconds later half- back John Short gathered in a flare pass to the right side and romped 22 yards down the sideline for the final touchdown of a perfect season.

That was one of a seemingly limitless assortment of plays that produced touchdowns during a memorable season. The same plays had worked in the past and they've continued to work, more often than not, to make Dartmouth's offense one of the most versatile and potent attacks in college football. A Dartmouth quarter- back can go through his bag of tricks and come up with several hundred variations, each one, in theory, designed to score a touchdown. This is the "multiple offense" developed during the last 20 years by Bob Blackman and Jake Crouthamel.

But Bear Bryant, paraphrasing a familiar line, struck the essence of what football is about when he observed, "If you want to make chicken salad, you start with chicken." A football game, no matter how you cut it, comes down to a matter of individual confrontations - me against you, eleven men against the other eleven in an orchestrated collection of hostilities. "You may win ten of the confrontations," says Jake Crouthamel, "but if there's one breakdown along the way it can cause the entire play to fail. That's why you see so few plays that result in big gains. Talk all you want, when it comes down to who wins and who loses, the X's and O's don't mean a thing. It's one-on-one, player against player, with all those people in the stands waiting to see what happens."

The basic principle of the Blackman- Crouthamel multiple offense permits adapting the attack to the personnel available rather than trying to make the players fit the offense. Also, what few observers realize is that Dartmouth's offense, in all its variety, is not built completely to the quarterback but rather to the fullback. "You adapt to the personality of your quarterback," says Crouthamel. "The give-and-take between the quarter- back and the rest of the team determines much of the personality of the offense. But Dartmouth uses five offensive series - in three of them the fullback is the key runner, in the other two the fullback is the key to the blocking."

Enter fullbacks like Pete Walton, Stuart Simms, Dave Boyle, and Ellis Rowe, vital elements in the Dartmouth success story. One of the reasons that the string of Ivy League championships ended last year was that none of the fullbacks who sifted through the backfield was able to operate with the effectiveness that Simms and Rowe demonstrated during the previous five seasons. Simms started 27 straight games from 1969-71, and Rowe proved an able successor during the next two seasons.

One of Dartmouth's most frequently used alignments is the "I" formation. From this set, with the fullback in the "up" position and the halfbacks either in the backfield or flanked to the side, comes much of the offensive power. Here are some of the plays that have been conspicuously effective in recent years - and why they've worked.

Heading into the final game of the 1973 season at Princeton, Rick Klupchak needed 130 yards to break Crouthamel's career record for rushing yardage. The Dartmouth halfback had appeared to be a cinch to get the record until he missed three games with a shoulder separation. Heading into the second half at Palmer Stadium, Dartmouth led by a shaky 14-11 margin and the record was still a question.

"He'd have had the record in the middle of the season if he hadn't been hurt," said Crouthamel, who told quarterback Tom Snickenberger to use the "speed option" through much of the final two periods. The play had Snick, Rowe, and Klupchak sprinting toward the end with the other halfback, Doug Lind, already flanked as a lead blocker. During the first half, Klupchak had gained only 47 yards, but with Lind blocking the cornerback and Snickenberger and Rowe charging ahead, Klupchak carried 13 times, gained 107 yards and scored three touchdowns in the last 30 minutes. To spice things up, Rowe punctuated one drive with three power runs that gained over 40 yards, and Dartmouth rolled to a 42-24 victory.

In the last game of the 1969 season, Princeton had worked Dartmouth over pretty well, beating the Green 35-7 behind Hank Bjorklund's three-touchdown barrage. When the Tigers came to Memorial Field in 1970, the power sweep became one of the most effective weapons in a 38-0 whitewashing of the team that had spoiled an undefeated season the year before.

John Short and Brendan O'Neill were the vehicles of destruction, but Chasey, Simms and guard Bob Cordy were the functional elements of the blocking scheme. The power sweep utilizes the fullback (Simms), quarterback (Chasey) and offside guard (Cordy) - the guard away from the direction the play will follow - to lead the interference against the defensive end. An awesome concentration of blocking spearheads the attack.

It was so effective on Short's touchdown run in the third period that when the half- back reached the goal line there was no Princeton defender left standing anywhere on the field and Short still had two blockers in front of him. It worked so well through the year that Short finished with a Dartmouth season record of 787 yards rushing and averaged nearly five yards every time he touched the ball. Later in the season at Harvard, Short used the play to devastate the Crimson with 106 yards and a pair of touchdowns in a 37-14 crunching.

Anyone who was in Harvard Stadium on October 27, 1973, will recognize the merits of the fullback off-tackle play, also known as the "Outside Belly Option." Working into a stiff headwind from the opening kickoff, Tom Snickenberger's first pitchout of the game fluttered wildly toward the Dartmouth goal line. Harvard recovered, but the Green defense held and the Crimson had to settle for a field goal.

In the next series, still contending with the wind with the goal line 89 yards away and with the passing game nullified by the powerful gusts, Snick stepped from the huddle. His call was the same as before: "L 42 Belly Option." He took the snap from center Bob Funk, offered and then withdrew the ball from Rowe's belly, and moved left behind the blocking toward Joe Mackey, the Harvard defensive end. Half- back John Souba, swinging wide, drew Mackey away and Snick cut inside the corner and headed upfield. Mackey was left behind, and Snick had reached midfield before the Crimson closed in. Trailing a step behind and a yard closer to the sideline was Souba. Snick flicked the ball to him and the Green halfback broke clear and had a touchdown in grasp, only to trip and fall at the Harvard four.

Two plays later, Snick wedged across with Dartmouth's first touchdown. At halftime the score was 24-3, and the rest of the game belonged to the award winning defense that made three goal-line stands in the second half and preserved a 24-18 victory.

Over the past 20 years, quarterbacks Beagle, Gundy, King, Beard, Chasey, Stetson, and Snickenberger have earned spots in the Dartmouth record book with their passing talents. (None will deny that their success owed much to convincing blocking.) If one man proved himself the master of the "sprint out pass," it was Chasey during the 1970 season.

Using halfback John Short and split end Bob Brown in a variety of flanking alignments, Chasey picked everybody apart with frightening consistency. It seemed virtually automatic that whenever Brown, who had sprinter speed and the versatility to turn in excellent decathlon performances in track, moved downfield and made his cuts, Chasey could produce guaranteed yardage.

Against Harvard during the classic season of '70, Chasey found Brown, Short, or Brendan O'Neill a total of 15 times for 181 yards. During the course of the season, Short and Brown caught 52 passes for over 600 yards.

If there has been a memorable piece of razzle-dazzle, one of those "alumni plays" that sticks in mind, it's the end-around piece of magic that Bob Brown executed for 39 yards and a totally unobstructed touchdown to cap a 55-0 victory over Columbia in 1970. It's a play that haunted the Green a year later because Columbia used "Remember 55-0" as its credo in 1971 and gained vengeance with a 31-29 victory over Dartmouth at Baker Field.

The "fun" plays are often the most difficult to execute because of their need for split-second timing. They're used sparingly, only when a situation dictates the need for something unexpected. One of those opportunities came during the 1973 game with Cornell at Memorial Field when Dartmouth led the Red, 10-0, in the fourth period and was in a position to kick a field goal.

On the sidelines, Crouthamel and his staff figured that a field goal might not be enough to win the game, so they called for the "fake field goal reverse." With fourth down and seven yards to go at the Cornell 24, George Carr replaced Tom Snickenberger as holder for kicker Ted Perry. Carr took the snap, placed it on the tee and Perry, who was late getting to the huddle and didn't know it was to be a fake kick, came through with his normal leg motion. To Perry's astonishment, Carr withdrew the ball and flipped it to split end Tom Fleming who was coming back from his blocking position on the left end. Fleming took the ball and turned down the right sideline for a first down that led to an eventual touchdown and a 17-0 victory. "The fake field goal was part of our play book all season but this was the first time we had a chance to use it," said Fleming. "I would have gone all the way except for one man."

Like it was diagrammed, fullback PeteWalton (opposite) slices Princeton, 1965.

"I" Formation

Speed Option

Power Sweep

Outside Belly Option

Sprint-out Pass

Fake Field Goal Reverse

Drew Tallman, Dartmouth's offensive linecoach from 1971-74, is now business manager for athletics at the College. Jack DeGange is Director of Sports Informationand writes about sports for this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe First 25 Years of the Dartmouth Bequest and Estate planning Program

September 1975 By Robert L. Kaiser '39 and Frank A. Logan '52 -

Feature

FeatureThe Computer Goes Fishing

September 1975 By DARREL MANSELL -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

September 1975 -

Feature

FeatureAn Irresistible Force?

September 1975 -

Feature

FeatureReport of the Office of Development

September 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Trials of Reggie

September 1975 By JACK DEGANGE

Features

-

Feature

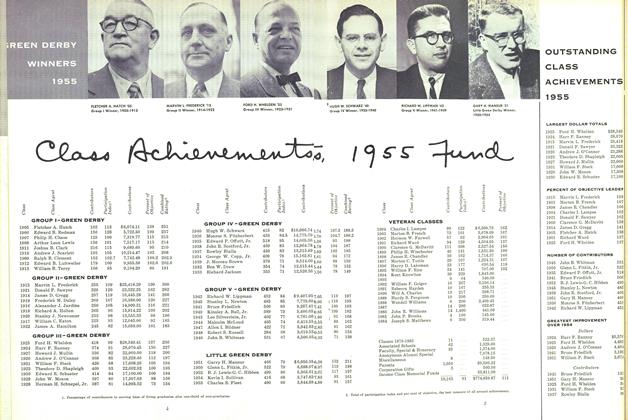

FeatureChass Achierement 1955 Fund

December 1955 -

Feature

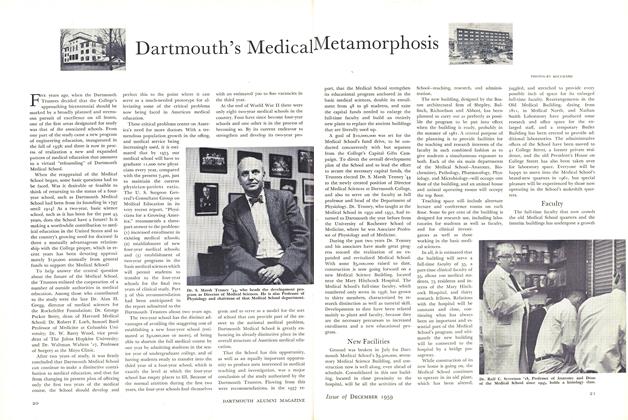

FeatureDartmouth's Medical Metamorphosis

December 1959 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Priorities for 1970

MARCH 1970 -

Feature

FeatureWomensports

JAN./FEB. 1979 -

Feature

FeatureTo Make What's Good Better

February 1951 By R. L. A. -

Feature

FeatureFraternity Discrimination Faces a Deadline

March 1960 By THOMAS E. GREEN '60