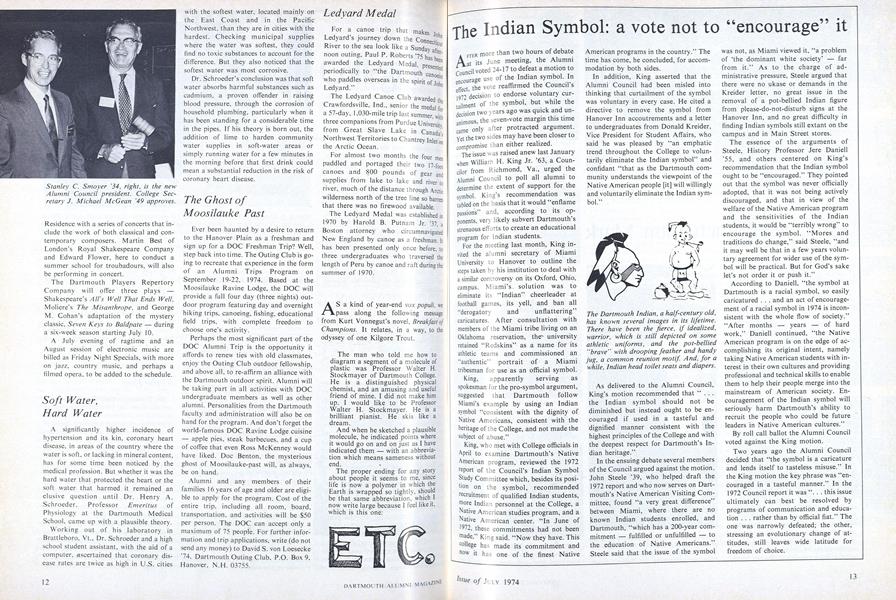

AFTER more than two hours of debate at its June meeting, the Alumni Council voted 24-17 to defeat a motion to encourage use of the Indian symbol. In effect, the vote reaffirmed the Council's 1972 decision to endorse voluntary curtailment of the symbol, but while the decision two years ago was quick and unanimous, the seven-vote margin this time came only after protracted argument. Yet the two sides may have been closer to compromise than either realized.

The issue was raised anew last January when William H. King Jr. '63, a Councilor Richmond, Va„ urged the Alumni Council to poll all alumni to determine the extent of support for the symbol. King's recommendation was tabled on the basis that it would "enflame passions" and, according to its opponents, very likely subvert Dartmouth's strenuous efforts to create an educational program for indian students.

For the meeting last month, King invited the alumni secretary of Miami University to Hanover to outline the steps taken by his institution to deal with a similar controversy on its Oxford, Ohio, campus. Miami's, solution was to eliminate its "Indian" cheerleader at football games, its yell, and ban all "derogatory and unflattering" caricatures. After consultation with members of the Miami tribe living on an Oklahoma reservation, the- university retained "Redskins" as a name for its athletic teams and commissioned an "authentic" portrait of a Miami tribesman for use as an official symbol.

King, apparently serving as spokesman for the pro-symbol argument, suggested that Dartmouth follow Miami's example by using an Indian symbol "consistent with the dignity of Native Americans, consistent with the heritage of the College, and not made the subject of abuse."

King, who met with College officials in April to examine Dartmouth's Native American program, reviewed the 1972 report of the Council's Indian Symbol Study Committee which, besides its position on the symbol, recommended recruitment of qualified Indian students, "lore Indian personnel at the College, a Native American studies program, and a Native American center. "In June of '972, these commitments had not been made, King said. "Now they have. This college has made its commitment and now it has one of the finest Native American programs in the country." The time has come, he concluded, for accommodation by both sides.

In addition, King asserted that the Alumni Council had been misled into thinking that curtailment of the symbol was voluntary in every case. He cited a directive to remove the symbol from Hanover Inn accoutrements and a letter to undergraduates from Donald Kreider, Vice President for Student Affairs, who said he was pleased by "an emphatic trend throughout the College to voluntarily eliminate the Indian symbol" and confidant "that as the Dartmouth community understands the viewpoint of the Native American people [it] will willingly and voluntarily eliminate the Indian symbol."

As delivered to the Alumni Council, King's motion recommended that "... the Indian symbol should not be diminished but instead ought to be encouraged if used in a tasteful and dignified manner consistent with the highest principles of the College and with the deepest respect for Dartmouth's Indian heritage."

In the ensuing debate several members of the Council argued against the motion. John Steele '39, who helped draft the 1972 report and who now serves on Dartmouth's Native American Visiting Committee, found "a very great difference" between Miami, where there are no known Indian students enrolled, and Dartmouth, "which has a 200-year commitment — fulfilled or unfulfilled to - the education of Native Americans." Steele said that the issue of the symbol was not, as Miami viewed it, "a problem of 'the dominant white society' - far from it." As to the charge of administrative pressure, Steele argued that there were no ukase or demands in the Kreider letter, no great issue in the removal of a pot-bellied Indian figure from please-do-not-disturb signs at the Hanover Inn, and no great difficulty in finding Indian symbols still extant on the campus and in Main Street stores.

The essence of the arguments of Steele, History Professor Jere Daniell '55, and others centered on King's recommendation that the Indian symbol ought to be "encouraged." They pointed out that the symbol was never officially adopted, that it was not being actively discouraged, and that in view of the welfare of the Native American program and the sensitivities of the Indian students, it would be "terribly wrong" to encourage the symbol. "Mores and traditions do change," said Steele, "and it may well be that in a few years voluntary agreement for wider use of the symbol will be practical. But for God's sake let's not order it or push it."

According to Daniell, "the symbol at Dartmouth is a racial symbol, so easily caricatured... and an act of encouragement of a racial symbol in 1974 is inconsistent with the whole flow of society." "After months years of hard work," Daniell continued, "the Native American program is on the edge of accomplishing its original intent, namely taking Native American students with interest in their own cultures and providing professional and technical skills to enable them to help their people merge into the mainstream of American society. Encouragement of the Indian symbol will seriously harm Dartmouth's ability to recruit the people who could be future leaders in Native American cultures."

By roll call ballot the Alumni Council voted against the King motion.

Two years ago the Alumni Council decided that "the symbol is a caricature and lends itself to tasteless misuse." In the King motion the key phrase was "encouraged in a tasteful manner." In the 1972 Council report it was "... this issue ultimately can best be resolved by programs of communication and education . . . rather than by official fiat." The one was narrowly defeated; the other, stressing an evolutionary change of attitudes, still leaves wide latitude for freedom of choice.

The Dartmouth Indian, a half-century old,has known several images in its lifetime.There have been the fierce, if idealized,warrior, which is still depicted on someathletic uniforms, and the pot-bellied"brave" with drooping feather and handyjug, a common reunion motif. And, for awhile, Indian head toilet seats and diapers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degrees

July 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureTruckin' from the Meat Bar

July 1974 By JOHN GANTZ -

Feature

FeatureThe Valedictories

July 1974 By LAN R. LAW '74, John G. Kemeny -

Feature

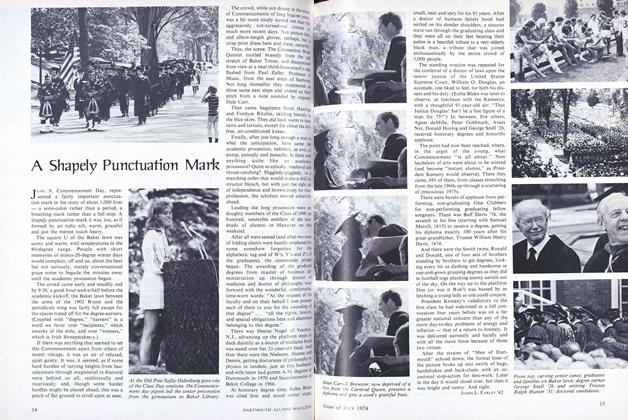

FeatureA Shapely Punctuation Mark

July 1974 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

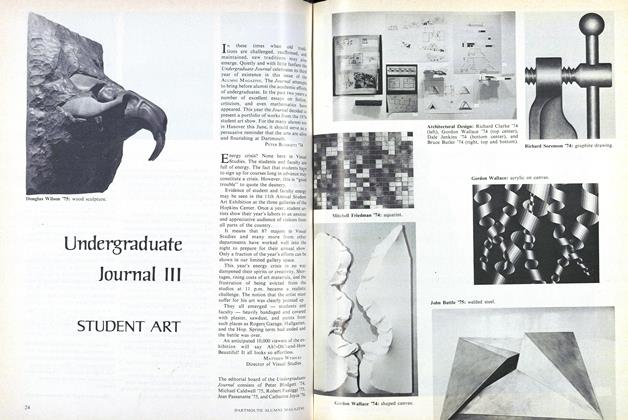

FeatureUndergraduate Journal III

July 1974 -

Article

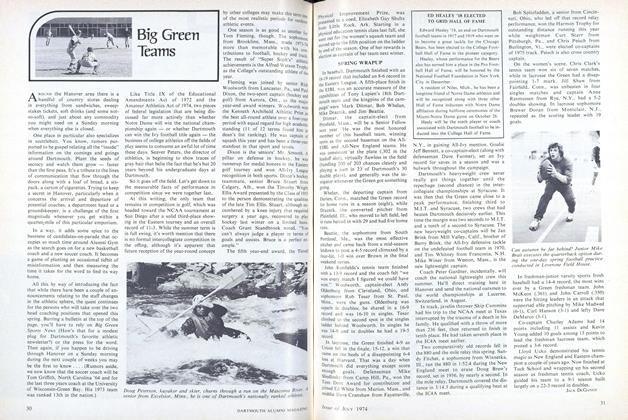

ArticleBig Green Teams

July 1974 By JACK DEGANGE