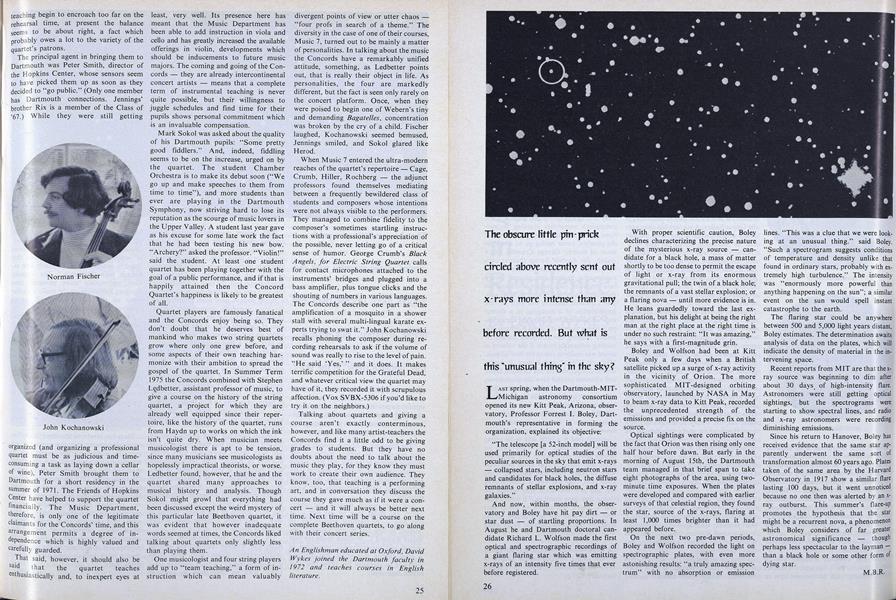

The obscure little pin-prick circled above recently sent out x-rays more intense than any before recorded. But what is this "unusual thing" in the sky?

October 1975 M.B.R.The obscure little pin-prick circled above recently sent out x-rays more intense than any before recorded. But what is this "unusual thing" in the sky? M.B.R. October 1975

LAST spring, when the Dartmouth-MIT-Michigan astronomy consortium opened its new Kitt Peak, Arizona, observatory, Professor Forrest I. Boley, Dartmouth's representative in forming the organization, explained its objective:

"The telescope [a 52-inch model] will be used primarily for optical studies of the peculiar sources in the sky that emit x-rays - collapsed stars, including neutron stars and candidates for black holes, the diffuse remnants of stellar explosions, and x-ray galaxies."

And now, within months, the observatory and Boley have hit pay dirt - or star dust - of startling proportions. In August he and Dartmouth doctoral candidate Richard L. Wolfson made the first optical and spectrographic recordings of a giant flaring star which was emitting x-rays of an intensity five times that ever before registered.

With proper scientific caution, Boley declines characterizing the precise nature of the mysterious x-ray source - candidate for a black hole, a mass of matter shortly to be too dense to permit the escape of light or x-ray from its enormous gravitational pull; the twin of a black hole; the remnants of a vast stellar explosion; or a flaring nova - until more evidence is in. He leans guardedly toward the last explanation, but his delight at being the right man at the right place at the right time is under no such restraint: "It was amazing," he says with a first-magnitude grin.

Boley and Wolfson had been at Kitt Peak only a few days when a British satellite picked up a surge of x-ray activity in the vicinity of Orion. The more sophisticated MIT-designed orbiting observatory, launched by NASA in May to beam x-ray data to Kitt Peak, recorded the unprecedented strength of the emissions and provided a precise fix on the source.

Optical sightings were complicated by the fact that Orion was then rising only one half hour before dawn. But early in the morning of August 15th, the Dartmouth team managed in that brief span to take eight photographs of the area, using two-minute time exposures. When the plates were developed and compared with earlier surveys of that celestial region, they found the star, source of the x-rays, flaring at least 1,000 times brighter than it had appeared before.

On the next two pre-dawn periods, Boley and Wolfson recorded the light on spectrographic plates, with even more astonishing results: "a truly amazing spectrum" with no absorption or emission lines. "This was a clue that we were looking at an unusual thing." said Boley. "Such a spectrogram suggests conditions of temperature and density unlike that found in ordinary stars, probably with extremely high turbulence." The intensity was "enormously more powerful than anything happening on the sun"; a similar event on the sun would spell instant catastrophe to the earth.

The flaring star could be anywhere between 500 and 5,000 light years distant, Boley estimates. The determination awaits analysis of data on the plates, which will indicate the density of material in the intervening space.

Recent reports from MIT are that the x-ray source was beginning to dim after about 30 days of high-intensity flare. Astronomers were still getting optical sightings, but the spectrograms were starting to show spectral lines, and radio and x-ray astronomers were recording diminishing emissions.

Since his return to Hanover, Boley has received evidence that the same star apparently underwent the same sort of transformation almost 60 years ago. Plates taken of the same area by the Harvard Observatory in 1917 show a similar flare lasting 100 days, but it went unnoticed because no one then was alerted by an xray outburst. This summer's flare-up promotes the hypothesis that the star might be a recurrent nova, a phenomenon which Boley considers of far greater astronomical significance - though perhaps less spectacular to the layman - than a black hole or some other form of dying star.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBefore the Revolution

October 1975 By ALBERT F. MONCURE JR., RONALD V. NEALE -

Feature

FeatureA Dialogue for Autumn

October 1975 By COREY FORD -

Feature

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe College

October 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Trolley Never Stopped Here

October 1975 By GEORGE W. HILTON

M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

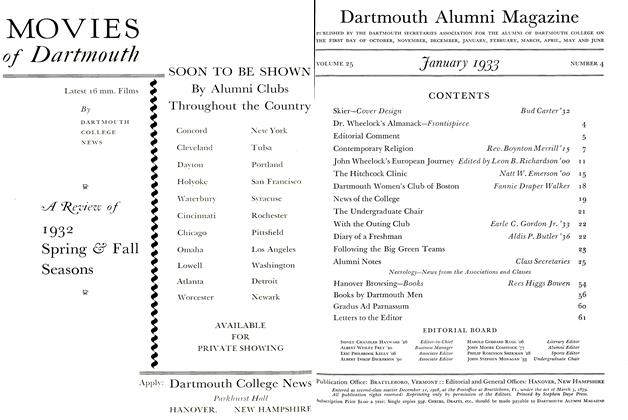

ArticleMasthead

January 1933 -

Article

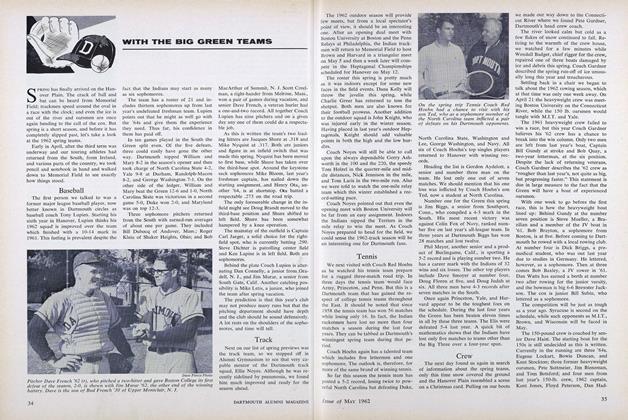

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

May 1962 -

Article

ArticleCommunity Engineering Service

APRIL 1973 -

Article

ArticleCouncil Ratifies New Constitution

SEPTEMBER 1996 -

Article

ArticleA Tribute to Natt W. Emerson, Practical Idealist

March 1936 By Homer Eaton Keyes '00 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

June 1940 By The Editor